Rafik Ward Q&A - final part

"Feedback we are getting from customers is that the current 100 Gig LR4 modules are too expensive"

Rafik Ward, Finisar

Q: Broadway Networks, why has Finisar acquired the company?

A: We spent quite some time talking to Broadway and understanding their business. We also talked to Broadway’s customers and the feedback we got on the technical team, the products and what this little start-up was able to accomplish was unanimously very positive.

We think what Broadway has done, for instance their EPON* stick product, is very interesting. With that product, an end user has the ability to make any SFP* port on a low-end Ethernet switch an EPON ONU* interface. This opens up a whole new set of potential customers and end users for EPON.

In reality, consumers will never have Ethernet switches with SFP ports in their house. Where we do see such Ethernet switches are in every major enterprise and many multi-dwelling units. It is an interesting technology that enables enterprises and multi-dwelling units to quickly tool-up for EPON.

* [EPON - Ethernet passive optical network, SFP - small form-factor pluggable optical transceiver, ONU - optical network unit]

Optical transceivers have been getting smaller and faster in the last decade yet laser and photo-detector manufacturing have hardly changed, except in terms of speed. Is this about to change?

Speed is one of the focus areas for the industry and will continue to be. Looking forward in a number of applications, though, we are going to hit the limit for these lasers and we are going to have to look more carefully outside of just raw laser speed to move up the data rate curve.

"We are going to hit the limit for these lasers"

A lot of this work has already started on the line side using different modulation formats and DSP* technology. Over time the question is: What happens on the client side? In future, do we look to other modulation formats on the client side? Eventually we will get there; it may take several years before we need to do things like that. But as an industry we would be foolish to think we won’t have to do this.

WDM* is going to be an increasingly important technology on the client side. We are already seeing this with the 40GBASE-LR4 and 100GBASE-LR4 standards.

* [DSP - digital signal processing, WDM - wavelength-division multiplexing]

Google gave a presentation at ECOC that argued for the need for another 100Gbps interface. What is Finisar’s view?

Feedback we are getting from customers is that the current 100 Gig LR4 modules are too expensive. We have spent a lot of time with customers helping them understand how the current LR4 standard, as is written, actually enables a very low cost optical interface, and the timeframes we believe are very quick in terms of how we can get cost down considerably on 100 Gig.  Rafik Ward (right) giving Glenn Wellbrock, director of backbone network design at Verizon Business, a tour of Finisar's labsThat was part of the details that [Finisar’s] Chris Cole also presented at ECOC.

Rafik Ward (right) giving Glenn Wellbrock, director of backbone network design at Verizon Business, a tour of Finisar's labsThat was part of the details that [Finisar’s] Chris Cole also presented at ECOC.

There has certainly been a lot of media attention on the two [ECOC] presentations between Finisar and Google. This really is not so much about the quote, ‘drama’, or two companies that have a disagreement which optical interface makes more sense. It is more fundamental than that.

What it comes down to is that, as an industry, we have pretty limited resources. The best thing all of us can do is try to direct these resources – this limited pool we have combined throughout the industry - on a path that makes the most sense to reduce bandwidth cost most significantly.

The best way to do that, and that is already established, is through standards. The [IEEE] standard got it right that the path the industry is on is going to enable the lowest cost 100 Gig [interface]. Like everything, there is some investment required to get us there. The 25 Gig technology now [used as 4x25 Gig] is becoming mainstream and will soon enable the lowest cost solution. My view is that within 18 months to two years this will be a moot point.

If the technology was available 18 months sooner, we wouldn’t even be having this discussion. But that is the position that we, as an industry, are in. With that, it creates some tensions, some turmoil, where customers don’t like to pay more than they perceive they have to.

There is the CFP form factor that is relatively large. Is the point that if current technology was available 18 months ago, 100Gbps could have come out in a QSFP?

The heart of the debate is cost.

There are other elements that always play into a debate like this. Beyond the cost argument, how quickly can two optical interfaces, like a 4x25 Gig versus a 10x10 Gig, each enable a smaller form factor solution.

But I think that is secondary. Had we not had the cost problem that we have now between 4x25 Gig versus 10x10 Gig, I don’t think we would be talking about it.

So it’s the current cost of the 4x25 Gig that is the issue?

Correct.

In September, the ECOC conference and exhibition was held. What were your impressions and did you detect any interesting changes?

There wasn’t so much an overwhelming theme this year at ECOC. In ECOC 2009, it was the year of coherent detection. This year there wasn’t a theme that resonated strongly throughout.

The mood was relatively upbeat. From our perspective, ECOC seemed a little bit smaller in terms of the size of the floor. But all the key people you would expect to be at the show were there.

Maybe the strongest theme – and I wrote about this in my blog – was colourless, directionless, contentionless (CDC) [ROADMs]. I think what I said is that they should have renamed it not ECOC but the ECDC show.

"A blog ... enables a much more informal mechanism to communicate to a broad audience."

Do you read business books and is there one that is useful for your job?

Probably the book I think about the most in my job is Clayton Christensen's The Innovator’s Dilemma.

He talks about how, when you look at very successful technology companies that have failed, what causes them to fail is often new solutions that come from the very low end of the market.

A lot of companies, and he cites examples from the disk drive industry, prided themselves on focussing on the high end of the market but ultimately ended up failing because there was a surprise upstart, someone who came in at the market's low end – in terms of performance, cost etc. – that continued to innovate using their low-end architecture, making it suitable for the core market.

For these large, well-established companies, once they realised they had this competitor, it was too late.

I think about that business book probably more than others. It’s a very interesting take on technology and the threat that can be posed to people in high-tech companies.

Your job sounds intensive and demanding. What do you do outside work to relax?

I’m a big [ice] hockey fan. I’ve been a hockey fan for many years; it’s a pretty intense sport. These days I tend to watch more hockey than I play but I very much enjoy the sport.

The other thing I started up this year that I had never done before – a little side project – was vegetable gardening. Surprisingly, it ended up taking a lot of my attention and I think it was a good distraction for me.

It can be quite remarkable, when you have your own little vegetable garden, how often you go and look at its progress. I’d find often coming home from work, first thing I’d want to do is go see how things were progressing in my vegetable garden.

You are the face of Finisar’s blog. What have you learnt from the experience?

A blog is an interesting tool to get information out to a broad audience. For companies like Finisar, it serves as a very important communication vehicle that didn’t exist previously.

In the old days, if you wanted to get information out to a broad group of customers, you either had to meet and communicate that information face-to-face, or via email; very targeted, one customer-at-a-time communication.

Another way was the press release. A press release was a very easy way to broadcast that information. But the challenge is that not all information that you want to broadcast is suitable for a press release.

The reason why I really like the blog is that it enables a much more informal mechanism to communicate to a broad audience.

Has it helped your job in any tangible way?

We found some interesting customer opportunities. These have come in through the blog when we’ve talked about specific products. That hasn’t happened extremely frequently but we have had a few instances. So it’s probably the most tangible thing: we can point to enhanced business because of it.

But the strength of something like a blog goes much deeper than that, in terms of the communication vehicle it enables.

You have about a year’s experience running a blog. If an optical component company is thinking about starting a blog, what is your advice?

The best advice I can give to anybody looking to do a blog is that it is something you have to commit to up-front.

A blog where you don’t continue to refresh the content regularly becomes a tired blog very quickly. We have made a conscious effort to have updated postings as best we can, on a weekly basis or even more frequently. There are certainly periods where we have gone longer than that but if you look back, in general, we have a wide variety of content that has been refreshed regularly.

I have to give credit to others - guest bloggers - within the organisation that help to maintain the content. This is critical. I would struggle to keep up with the pace if it was just myself every week.

Click here for the first part of Rafik Ward's Q&A.

Q&A with Rafik Ward - Part 1

"This is probably the strongest growth we have seen since the last bubble of 1999-2000." Rafik Ward, Finisar

"This is probably the strongest growth we have seen since the last bubble of 1999-2000." Rafik Ward, Finisar

Q: How would you summarise the current state of the industry?

A: It’s a pretty fun time to be in the optical component business, and it’s some time since we last said that.

We are at an interesting inflexion point. In the past few years there has been a lot of emphasis on the migration from 1 to 2.5 Gig to 10 Gig. The [pluggable module] form factors for these speeds have been known, and involved executing on SFP, SFP+ and XFPs.

But in the last year there has been a significant breakthrough; now a lot of the discussion with customers are around 40 and 100 Gig, around form factors like QSFP and CFP - new form factors we haven’t discussed before, around new ways to handle data traffic at these data rates, and new schemes like coherent modulation.

It’s a very exciting time. Every new jump is challenging but this jump is particularly challenging in terms of what it takes to develop some of these modules.

From a business perspective, certainly at Finisar, this is probably the strongest growth we have seen since the last bubble of 1999-2000. It’s not equal to what it was then and I don’t think any of us believes it will be. But certainly the last five quarters has been the strongest growth we’ve seen in a decade.

What is this growth due to?

There are several factors.

There was a significant reduction in spending at the end of 2008 and part of 2009 where end users did not keep up with their networking demands. Due to the global financial crisis, they [service providers] significantly cut capex so some catch-up has been occurring. Keep in mind that during the global financial crisis, based on every metric we’ve seen, the rate of bandwidth growth has been unfazed.

From a Finisar perspective, we are well positioned in several markets. The WSS [wavelength-selective switch] ROADM market has been growing at a steady clip while other markets are growing quite significantly – at 10 Gig, 40 Gig and even now 100 Gig. The last point is that, based on all the metrics we’ve seen, we are picking up market share.

Your job title is very clear but can you explain what you do?

I love my job because no two days are the same. I come in and have certain things I expect to happen and get done yet it rarely shapes out how I envisaged it.

There are really three elements to my job. Product management is the significant majority of where I focus my efforts. It’s a broad role – we are very focussed on the products and on the core business to win market share. There is a pretty heavy execution focus in product management but there is also a strategic element as well.

The second element of my job is what we call strategic marketing. We spend time understanding new, potential markets where we as Finisar can use our core competencies, and a lot of the things we’ve built, to go after. This is not in line with existing markets but adjacent ones: Are there opportunities for optical transceivers in things like military and consumer applications?

One of the things I’m convinced of is that, as the price of optical components continues to come down, new markets will emerge. Some of those markets we may not even know today, and that is what we are finding. That’s a pretty interesting part of my job but candidly I spend quite a bit less time on it [strategic marketing] than product management.

The third area is corporate communications: talking to media and analysts, press releases, the website and blog, and trade shows.

"40Gbps DPSK and DQPSK compete with each other, while for 40 Gig coherent its biggest competitor isn’t DPSK and DQPSK but 100 Gig."

Some questions on markets and technology developments.

Is it becoming clearer how the various 40Gbps line side optics – DPSK, DQPSK and coherent – are going to play out?

The situation is becoming clearer but that doesn’t mean it is easier to explain.

The market is composed of customers and end users that will use all of the above modulation formats. When we talk to customers, every one has picked one, two or sometimes all three modulation formats. It is very hard to point to any trend in terms of picks, it is more on a case-by-case basis. Customers are, like us at the component level, very passionate about the modulation format that they have chosen and will have a variety of very good reasons why a particular modulation format makes sense.

Unlike certain markets where you see a level of convergence, I don’t think that there will be true convergence at 40 Gbps. Coherent – DP-QPSK - is a very powerful technology but the biggest challenge 40 Gig has with DP-QPSK is that you have the same modulation format at 100 Gig.

The more I look at the market, 40Gbps DPSK and DQPSK compete with each other, while for 40 Gig coherent its biggest competitor isn’t DPSK and DQPSK but 100 Gig.

Finisar has been quiet about its 100 Gig line side plans, what is its position?

We view these markets - 40 and 100 Gig line side – as potentially very large markets at the optical component level. Despite that fact that there are some customers that are doing vertical integrated solutions, we still see these markets as large ones. It would be foolish for us not to look at these markets very carefully. That is probably all I would say on the topic right now.

"Photonic integration is important and it becomes even more important as data rates increase."

Finisar has come out with an ‘optical engine’, a [240Gbps] parallel optics product. Why now?

This is a very exciting part of our business. We’ve been looking for some time at the future challenges we expect to see in networking equipment. If you look at fibre optics today, they are used on the front panel of equipment. Typically it is pluggable optics, sometimes it is fixed, but the intent is that the optics is the interface that brings data into and out of a chassis.

People have been using parallel optics within chassis – for backplane and other applications – but it has been niche. The reason it’s niche is that the need hasn’t been compelling for intra-chassis applications. We believe that need will change in the next decade. Parallel optics intra-chassis will be needed just to be able to drive the amount of bandwidth required from one printed circuit board to another or even from one chip to another.

The applications driving this right now are the very largest supercomputers and the very largest core routers. So it is a market focussed on the extreme high-end but what is the extreme high-end today will be mainstream a few years from now. You will see these things in mainstream servers, routers and switches etc.

Photonic integration – what’s happening here?

Photonic integration is something that the industry has been working on for several years in different forms; it continues to chug on in the background but that is not to understate its importance.

For vendors like Finisar, photonic integration is important and it becomes even more important as data rates increase. What we are seeing is that a lot of emerging standards are based around multiple lasers within a module. Examples are the 40GBASE-LR4 and the 100GBASE-LR4 (10km reach) standards, where you need four lasers and four photo-detectors and the corresponding mux-demux optics to make that work.

The higher the number of lasers required inside a given module, and the more complexity you see, the more room you have to cost-reduce with photonic integration.

Bringing WDM-PON to market

"We see just one way to bring down the cost, form-factor and energy consumption of the OLT’s multiple transceivers: high integration of transceiver arrays"

Klaus Grobe, ADVA Optical Networking

Considerable engineering effort will be needed to make next-generation optical access schemes using multiple wavelengths competitive with existing passive optical networks (PONs).

Such a multi-wavelength access scheme, known as a wavelength division multiplexing-passive optical network (WDM-PON), will need to embrace new architectures based on laser arrays and reflective optics, and use advanced photonic integration to meet the required size, power consumption and cost targets.

Current PON technology uses a single wavelength to deliver downstream traffic to end users. A separate wavelength is used for upstream data, with each user having an assigned time slot to transmit.

Gigabit PON (GPON) delivers 2.5 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) to between 32 or 64 users, while the next development, XG-PON, will extend GPON’s downstream data rate to 10 Gbps. The alternative PON scheme, Ethernet PON (EPON), already has a 10 Gbps variant. Vendors are also extending PON’s reach from 20km to 80km or more using signal amplification.

But the industry view is that after 10 Gigabit PON, the next step will be to introduce multiple wavelengths to extend the capacity beyond what a time-sharing approach can support. Extending the access network's reach to 100km will also be straightforward using WDM transport technology.

The advent of WDM-PON is also an opportunity for new entrants, traditional WDM optical transport vendors, to enter the access market. ADVA Optical Networking is one firm that has been vocal about its plans to develop next-generation access systems.

“We are seriously investigating and developing a next-generation access system and it is very likely that it will be a flavour of WDM-PON,” says Klaus Grobe, senior principal engineer at ADVA Optical Networking. “It [next-generation access] must be based on WDM simply because of bandwidth requirements.”

The system vendor views WDM-PON as addressing three main applications: wireless backhaul, enterprise connectivity and residential broadband. But despite WDM-PON’s potential to reduce operating costs significantly, the challenge facing vendors is reducing the cost of WDM-PON hardware. Indeed it is the expense of WDM-PON systems that so far has assigned the technology to specialist applications only.

A non-reflective tunable laser-based WDM-PON ONU. Source: ADVA Optical NetworkingAccording to Grobe, cost reduction is needed at both ends of the WDM-PON: the client receiver equipment known as the optical networking unit (ONU) and the optical line terminal (OLT) housed within an operator’s central office.

A non-reflective tunable laser-based WDM-PON ONU. Source: ADVA Optical NetworkingAccording to Grobe, cost reduction is needed at both ends of the WDM-PON: the client receiver equipment known as the optical networking unit (ONU) and the optical line terminal (OLT) housed within an operator’s central office.

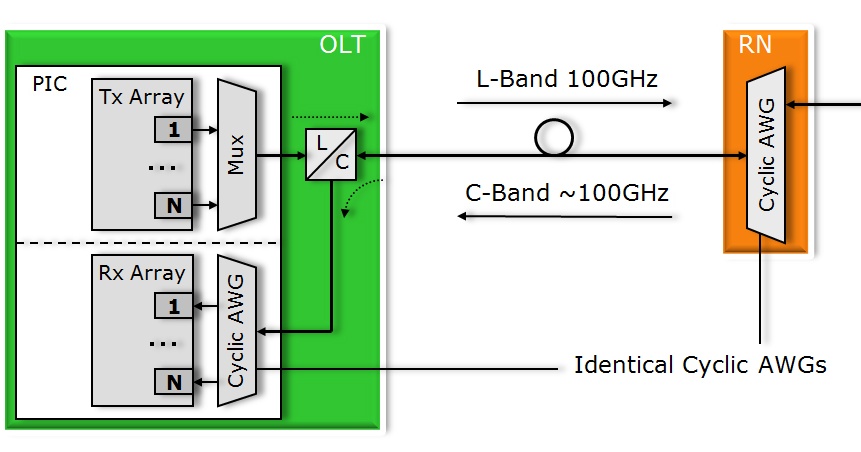

ADVA Optical Networking plans to use low-cost tunable lasers rather than a broadband light source and reflective optics for the ONU transceivers. “For the OLT, we see just one way to bring down the cost, form-factor and energy consumption of the OLT’s multiple transceivers: high integration of transceiver arrays,” says Grobe.

This is a considerable photonic integration challenge: a 40- or 80-wavelength WDM-PON uses 40 or 80 transceiver bi-directional clients, equating to 80 and 160 wavelengths. If 80 SFPs optical modules were used at the OLT, the resulting cost, size and power consumption would be prohibitive, says Grobe.

ADVA Optical Networking is working with several firms, one being CIP Technologies, to develop integrated transceiver arrays. ADVA Optical Networking and CIP Technologies are part of the EU-funded project, C-3PO, that includes the development of integrated transceiver arrays for WDM-PON.

Splitters versus filters

One issue with WDM-PON is that there is no industry-accepted definition. ADVA Optical Networking views WDM-PON as an architecture based on optical filters rather than splitters. Two consequences result once that choice is made, says Grobe.

One is insertion loss. Choosing filters implies arrayed waveguide gratings (AWGs), says Grobe. “No other filter technology is seriously considered for WDM-PON if filters are used,” he says.

With an AWG, the insertion loss is independent of the number of wavelengths supported. This differs from using a splitter-based architecture where every 1x2 device introduces a 3dB loss - “closer to 3.5dB”, he says. Using a 1x64 splitter, the insertion loss is 14 or 15dB whereas for a 40-channel AWG the loss can be as low as 4dB. “I just saw specs of a first 96-channel AWG, even that one isn’t much higher [than 4dB],” says Grobe. Thus using filters rather than splitters, the insertion loss is much lower for a comparable number of client ONUs.

There is also a cost benefit associated with a low insertion loss. To limit the cost of next-generation PON, the transceiver design must be constrained to a 25dB power budget associated with existing PON transceivers. “This is necessary to keep these things cheap, possibly dirt cheap,” says Grobe.

The alternative, using XG-PON’s sophisticated 10 Gbps burst-mode transceiver with its associated 35dB power budget, achieving low cost is simply not possible, he says. To live with transceivers with a 25dB power budget, the insertion loss of the passive distribution network must be minimised, explaining why filters are favoured.

The other main benefit of using filters is security. With a filter-based PON, wavelength point-to-point connections result. “You are not doing broadcast,” says Grobe. “You immediately get rid of almost all security aspects.” This is an issue with PON where traffic is shared.

Low power

Achieving a low-power WDM-PON system is another key design consideration. “In next-gen access, it is absolutely vital,” says Grobe. “If the technology is deployed on a broad scale - that is millions of user lines – every single watt counts, otherwise you end up with differences in the approaches that go into the megawatts and even gigawatts.”

There is also a benchmarking issue, says Grobe: the WDM-PON OLT will be compared to XG-PON’s even if the two schemes differ. Since XG-PON uses time-division multiplexing, there will be only one transceiver at the OLT. But this is what a 40- or 80-channel WDM-PON OLT will be compared with, even if the comparison is apples to pears, says Grobe.

WDM-PON workings

There are two approaches to WDM-PON.

In a fully reflective architecture, the OLT array and the ONUs are seeded using multi-wavelength laser arrays; both ends use the lasers arrays in combination with reflective optics for optical transmission.

ADVA Optical Networking is interested in using a reflective approach at the OLT but for the ONU it will use tunable lasers due to technical advantages. For example, using the same wavelength for the incoming and modulated streams in a reflective approach, Rayleigh crosstalk is an issue when the ONUs are 100km from the OLT. In contrast, Rayleigh crosstalk at the OLT is avoided because the multi-wavelength laser array is located only a few metres from the reflective electro-absorption modulators (REAMs).

REAMs are used rather than semiconductor optical amplifiers (SOAs) to modulate data at the OLT because they support higher bandwidth 10 Gbps wavelengths. Indeed the C-3PO project is likely to use a monolithically integrated SOA-REAM for this task. “The reflective SOA is narrower in bandwidth but has inherent gain while the REAM has loss rather than gain – it is just a modulator,” says Grobe. “The combination of the two is the ideal: giving high modulation bandwidth and high transmit power.”

The integrated WDM-PON OLT. In practice the transmit array uses a reflective architecture based on SOA-REAMs and is fed with a multi-wavelength laser source. Source: ADVA Optical Networking

The integrated WDM-PON OLT. In practice the transmit array uses a reflective architecture based on SOA-REAMs and is fed with a multi-wavelength laser source. Source: ADVA Optical Networking

For the OLT, a multi-wavelength laser is fed via an AWG into an array of SOA-REAMs which modulate the wavelengths and return them through the AWG where they are multiplexed and transmitted to the ONUs via a demultiplexing AWG. An added benefit of this approach, says Grobe, is that the same multi-wavelength laser source can be use to feed several WDM-PON OLTs, further decreasing system cost.

For the upstream path, each ONU’s wavelength is separated by the OLT’s AWG and fed to the receiver array. In a WDM-PON system, the OLT transmit wavelengths and receive wavelengths (from the ONUs) operate in separate optical bands.

Grobe expects its resulting WDM-PON system to use 40 or 80 channels. And to best meet size, power and cost constraints, the OLT design will likely implemented as a photonic integrated circuit. “We are after a single PIC solution,” he says. “It is clear that with the OLT, integration is the only way to meet requirements.” A photonically-integrated OLT design is one of the products expected from the C-3PO project, using CIP Technologies' hybrid integration technology.

ADVA Optical Networking has already said that its WDM-PON OLT will be implemented using its FSP 3000 platform.

- To see some WDM-PON architecture slides, click here.

Reflecting light to save power

System vendors will be held increasingly responsible for the power consumption of their telecom and datacom platforms. That’s because for each watt the equipment generates, up to six watts is required for cooling. It is a burden that will only get heavier given the relentless growth in network traffic.

"Enterprises are looking for huge capacity at low cost and are increasingly concerned about the overall impact on power consumption"

"Enterprises are looking for huge capacity at low cost and are increasingly concerned about the overall impact on power consumption"

David Smith, CIP Technologies

No surprise, then, that the European 7th Framework Programme has kicked-off a research project to tackle power consumption. The Colorless and Coolerless Components for Low-Power Optical Networks (C-3PO) project involves six partners that include component specialist CIP Technologies and system vendors ADVA Optical Networking.

CIP is the project’s sole opto-electronics provider while ADVA Optical Networking's role is as system integrator.

“It’s not the power consumption of the optics alone,” says David Smith, CTO of CIP Technologies. “The project is looking at component technology and architectural issues which can reduce overall power consumption.”

The data centre is an obvious culprit, requiring up to 5 megawatts. Power is consumed by IT and networking equipment within the data centre – not a C-3PO project focus – and by optical networking equipment that links the data centre to other sites. “Large enterprises have to transport huge amounts of capacity between data centres, and requirements are growing exponentially,” says Smith. “They [enterprises] are looking for huge capacity at low cost and are increasingly concerned about the overall impact on power consumption.”

One C-3PO goal is to explore how to scale traffic without impacting the data centre’s overall power consumption. Conventional dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) equipment isn’t necessarily the most power-efficient given that DWDM tunable lasers requires their own cooling. “There is the power that goes into cooling the transponder, and to get the heat away you need to multiply again by the power needed for air conditioning,” says Smith.

Another idea gaining attention is operating data centres at higher ambient temperatures to reduce the air conditioning needed. This idea works with chips that have a wide operating temperature but the performance of optics - indium phosphide-based actives - degrade with temperature such that extra cooling is required. As such, power consumption could even be worse, says Smith

A more controversial optical transport idea is changing how line-side transport is done. Adding transceivers directly to IP core routers saves on the overall DWDM equipment deployed. This is not a new idea, says Smith, and an argument against this is it places tunable lasers and their cooling on an IP router which operates at a relatively high ambient temperature. The power reduction sought may not be achieved.

But by adopting a new transceiver design, using coolerless and colourless (reflective) components, operating at a wider temperature range without needing significant cooling is possible. “It is speculative but there is a good commercial argument that this could be effective,” says Smith.

C-3PO will also exploit material systems to extend devices’ temperature range - 75oC to 85oC - to eliminate as much cooling as possible. Such material systems expertise is the result of CIP’s involvement in other collaborative projects.

"If the [WDM-PON] technology is deployed on a broad scale - that is millions of user lines – every single watt counts"

Klaus Grobe, ADVA Optical Networking

Indeed a companion project, to be announced soon, will run alongside C-3PO based on what Smith describes as ‘revolutionary new material systems’. These systems will greatly improve the temperature performance of opto-electronics. “C-3PO is not dependent on this [project] but may benefit from it,” he says.

Colourless and coolerless

CIP’s role in the project will be to integrate modulators and arrays of lasers and detectors to make coolerless and colourless optical transmission technology. CIP has its own hybrid optical integration technology called HyBoard.

“Coolerless is something that will always be aspirational,” says Smith. C-3PO will develop technology to reduce and even eliminate cooling where possible to reduce overall power consumption. “Whether you can get all parts coolerless, that is something to be strived for,” he says.

Colourless implies wavelength independence. For light sources, one way to achieve colourless operation is by using tunable lasers, another is to use reflective optics.

CIP Technologies has been working on reflective optics as part of its work on wavelength division multiplexing, passive optical networks (WDM-PON). Given such reflective optics work for distances up to 100km for optical access, CIP has considered using the technology for metro and enterprise networking applications.

Smith expects the technology to work over 200-300km, at data rates from 10 to 28 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) per channel. Four 28Gbps channels would enable low-cost 100Gbps DWDM interfaces.

Reflective transmission

CIP’s building-block components used for colourless transmission include a multi-wavelength laser, an arrayed waveguide grating (AWG), reflective modulators and receivers (see diagram).

Reflective DWDM architecture. Source: CIP Technologies

Reflective DWDM architecture. Source: CIP Technologies

Smith describes the multi-wavelength laser as an integrated component, effectively an array of sources. This is more efficient for longer distances than using a broadband source that is sliced to create particular wavelengths. “Each line is very narrow, pure and controlled,” says Smith.

The laser source is passed through the AWG which feds individual wavelengths to the reflective modulators where they are modulated and passed back through the AWG. The benefit of using a reflective modulator rather than a pass-through one is a simpler system. If the light source is passed through the modulator, a second AWG is needed to combine all the sources, as well as a second fibre. Single-ended fibre is also simpler to package.

For data rates of 1 or 2Gbps, the reflective modulator used can be a reflective semiconductor optical amplifier (RSOA). At speeds of 10Gbps and above, the complementary SOA-REAM (reflective electro-absorption modulator) is used; the REAM offers a broader bandwidth while the SOA offers gain.

The benefit of a reflective scheme is that the laser source, made athermal and coolerless, consumes far less power than tunable lasers. “It has to be at least half the cost and we think that is achievable,” says Smith.

Using the example of the IP router, the colourless SFP transceiver – made up of a modulator and detector - would be placed on each line card. And the multi-wavelength laser source would be fed to each card’s module.

Another part of the project is looking at using arrays of REAMs for WDM-PON. Such an modulator array would be used at the central office optical line terminal (OLT). “Here there are real space and cost savings using arrays of reflective electro-absorption modulators given their low power requirements,” says Smith. “If we can do this with little or no cooling required there will be significant savings compared to a tunable laser solution.”

ADVA Optical Networking points out that with an 80-channel WDM-PON system, there will be a total of 160 wavelengths (see the business case for WDM-PON). “If you consider 80 clients at the OLT being terminated with 80 SFPs, there will be a cost, energy consumption and form-factor overkill,” says Klaus Grobe, senior principal engineer at ADVA Optical Networking. “The only known solution for this is high integration of the transceiver arrays and that is exactly what C-3PO is about.”

The low-power aspect of C-3PO for WDM-PON is also key. “In next-gen access, it is absolutely vital,” says Grobe. “If the technology is deployed on a broad scale - that is millions of user lines – every single watt counts, otherwise you end up with differences in the approaches that go into the megawatts and even gigawatts.”

There is also a benchmarking issue: the WDM-PON OLT will be compared to the XG-PON standard, the next-generation 10Gbps Gigabit passive optical network (GPON) scheme. Since XG-PON will use time-division multiplexing, there will be only one transceiver at the OLT. But this is what a 40- or 80-channel WDM-PON OLT will be compared with.

There is also a benchmarking issue: the WDM-PON OLT will be compared to the XG-PON standard, the next-generation 10Gbps Gigabit passive optical network (GPON) scheme. Since XG-PON will use time-division multiplexing, there will be only one transceiver at the OLT. But this is what a 40- or 80-channel WDM-PON OLT will be compared with.

CIP will also be working closely with 3-CPO partner, IMEC, as part of the design of the low-power ICs to drive the modulators.

Project timescales

The C-3PO project started in June 2010 and will last three years. The total funding of the project is €2.6 million with the European Union contributing €1.99 million.

The project will start by defining system requirements for the WDM-PON and optical transmission designs.

At CIP the project will employ the equivalent of two full-time staff for the project’s duration though Smith estimates that 15 CIP staff will be involved overall.

ADVA Optical Networking plans to use the results of the project – the WDM-PON and possibly the high-speed transmission interfaces - as part of its FSP 3000 WDM platform.

CIP expects that the technology developed as part of 3-CPO will be part of its advanced product offerings.

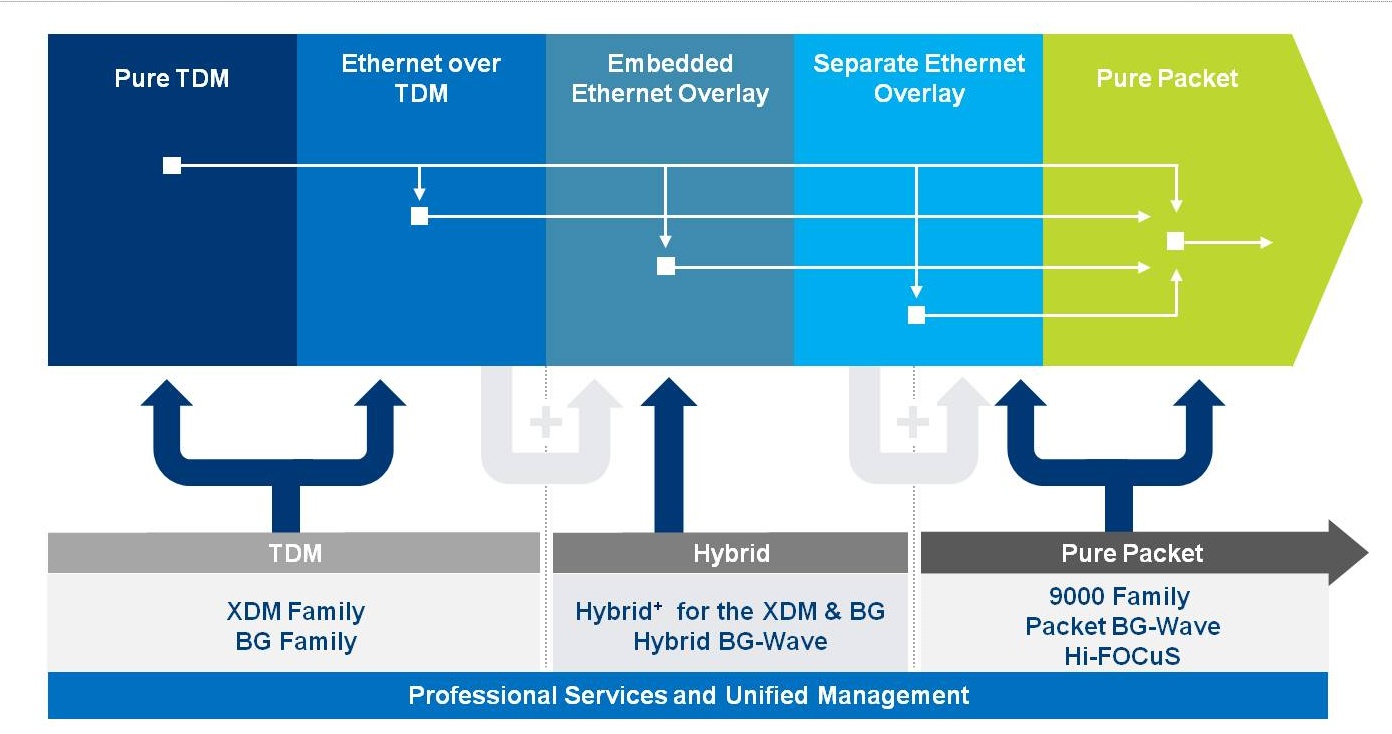

Wireless backhaul: The many routes to packet

ECI Telecom has detailed its wireless backhaul offering that spans the cell tower to the metro network. The 1Net wireless backhaul architecture supports traditional Sonet/SDH to full packet transport, with hybrid options in between, across various physical media.

“We can support any migration scheme an operator may have over any type of technology and physical medium, be it copper, fibre or microwave,” says Gil Epshtein, senior product marketing manager, network solutions division at ECI Telecom.

Why is this important?

Operators are experiencing unprecedented growth in wireless data due to the rise of smart phones and notebooks with 3G dongles for mobile broadband.

Mobile data surpassed voice traffic for the first time in December 2009, according to Ericsson, with the crossover occurring at approximately 140,000 terabytes per month in both voice and data traffic. According to Infonetics Research, mobile broadband subscribers surpassed digital subscriber line (DSL) subscribers in 2009, and will grow to 1.5 billion worldwide in 2014. By then, there will be 3.6 exabytes (3.6 billion gigabytes) per month of mobile data traffic, with two thirds being wireless video, forecasts Cisco Systems.

“The challenge is that almost all the growth is packet internet traffic, and that is not well suited to sit on the classic TDM backhaul network originally designed for voice,” says Michael Howard, principal analyst, carrier and data center networks at Infonetics Research. TDM refers to time division multiplexing based on Sonet/SDH where for wireless backhaul T1/E1lines are used.

“There is a gap between the technology hype and real life”

Gil Epshtein, ECI Telecom

The fast growth also implies an issue of scale, with the larger mobile operators having many cell sites to backhaul. E1/TI lines are also expensive even if prices are coming down, says Howard: “It is much cheaper to use Ethernet as a transport – the cost per bit is enormously better.”

This is why operators are keen to upgrade their wireless backhaul networks from Sonet/SDH to packet-based Ethernet transport. “But there is a gap between the technology hype and real life,” says Epshtein. Operators have already invested heavily in existing backhaul infrastructure and upgrading to packet will be costly. The operators also know that projected revenues from data services will not keep pace with traffic growth.

“Operators are faced with how to build out their backhaul infrastructures to meet service demands at cost points that provide an adequate return on investment,” says Glen Hunt, principal analyst, carrier transport and routing at Current Analysis. Such costs are multi-faceted, he says, on the capital side and the operational side. “Carriers do not want to buy an inexpensive device that adds complexity to network operations which then offsets any capital savings.”

“It is much cheaper to use Ethernet as a transport –the cost per bit is enormously better.”

Michael Howard, Infonetics Research

To this aim, ECI offers operators a choice of migration schemes to packet-based backhaul. Its solution supports T1/E1lines and Ethernet frame encapsulation over TDM, Ethernet overlay networks, and packet-only networks (see chart above).

With Ethernet overlay, an Ethernet network runs alongside the TDM network. The two can co-exist within a common network element, what ECI calls embedded Ethernet overlay, or separately using distinct TDM and packet switch platforms. And when an operator adopts all-packet, legacy TDM traffic can be carried over packets using circuit emulation pseudo-wire technology.

“ECI’s offering is significant since it includes all the components and systems necessary to handle nearly any type of backhaul requirement,” says Hunt. The same is true for most of the larger system vendors, he says. However, many vendors integrate third party devices to complete their solutions – ECI itself has done this with microwave. But with 1NET for wireless backhaul, ECI will now offer its own microwave backhaul systems.

According to Infonetics, between 55% and 60% of all backhaul links are microwave outside of North America. And 80% of all microwave sales are for mobile backhaul. Moreover, Infonetics estimates that 70 to 80% of operator spending on mobile backhaul through 2012 will be on microwave. “Those are the figures that explain why ECI has decided to go it alone,” says Howard. Until now ECI has used products from its microwave specialist partner, Ceragon Networks.

“ECI has all the essential features that the other big players have like Ericsson, Alcatel-Lucent, Nokia Siemens Networks and Huawei,” says Howard. What is different is that ECI does not supply radio access network (RAN) equipment such as basestations. “It is ok, though, because almost all of the [operator] backhaul tenders separate between RAN and backhaul,” says Howard.

ECI argues that by adopting a technology-agnostic approach, it can address operators’ requirements without forcing them down a particular path. “Operators are looking for guidance as to which path is best from this transition,” says Epshtein. There is no one-model fits all. “We have so many exceptions you really need to look on a case-by-case basis.”

In developed markets, for example, the building of packet overlay is generally happening faster. Some operators with fixed line networks have already moved to packet and that, in theory, simplifies upgrading the backhaul to packet. But organisational issues across an operator’s business units can complicate and delay matters, he says.

And Epshtein cites one European operator that will use its existing network to accommodate growth in data services over the coming years: “It is putting aside the technology hype and looking at the bottom line."

In emerging markets, moving to packet is happening more slowly as mobile users’ income is limited. But on closer inspection this too varies. In Africa, certain operators are moving straight to all-IP, says Ephstein, whereas others are taking a gradual approach.

What’s been done?

ECI has launched new products as well as upgraded existing ones as part of its 1NET wireless backhaul offering.

The company has announced its BG-Wave microwave systems. There are two offerings: an all-packet microwave system and a hybrid one that supports both TDM and Ethernet traffic. ECI says that having its own microwave products will allow it to gain a foothold with operators it has not had design wins before.

“ECI will need to prove the value of its microwave products with actual field deployments”

Glen Hunt, Current Analysis

ECI has announced two additional 9000 carrier Ethernet switch routers (CESR) families: the 9300 and 9600. These have switching capacities and a product size more suited to backhaul. The switches support Layer 3 IP-MPLS and Layer 2 MPLS-TP, as well as the SyncE and IEEE 1588 Version 2 synchronisation protocols.

ECI has also upgraded its XDM multi-service provisioning platform (MSPP) to enable an embedded overlay with Ethernet and TDM traffic supported within the platform.

“When an operator is choosing to add packet backhaul to existing TDM backhaul, typically it is a separate network – they keep voice on TDM and add a second network for packet,” says Howard. This hybrid approach involves adding another set of equipment. “ECI has added functions to existing equipment, which operators may already have, that allows two networks to run over a single set of products.”

Also included in the solution are ECI’s BroadGate and its Hi-FOCuS multi-service access node (MSAN). This is not for operators to deploy the platform for wireless backhaul but rather those operators that have the MSAN can now use it for backhauling traffic, says Ephstein. This is useful in dense urban areas and for operators offering wholesale services to other operators.

All the network elements are controlled using ECI’s LightSoft management system.

“ECI’s solution has the advantage that all the systems use the same operating system and support the same features,” says Hunt. He cites the example of MPLS-TP which is implemented on ECI’s carrier Ethernet and optical platforms.

“ECI has a full range of platforms that all work together to meet the needs of mobile as well as fixed operator,” says Hunt. “ECI will need to prove the value of its microwave products with actual field deployments.”

Operator interest

ECI has secured general telecom wins with large incumbent operators in Western Europe and has been winning business in Eastern Europe, Russia, India and parts of Asia.

ECI’s sweet spot has been its relationship with Tier 2 and Tier 3 operators, says Hunt, and since the company offers broadband access, optical transport, and carrier Ethernet, it can use these successes to help expand into areas such as wireless backhaul.

But wireless backhaul is already a key part of the company’s business, accounting for over 30% of revenues, says Ephstein. Late last year ECI estimated that it was carrying between 30% and 40% of the mobile backbone traffic in India, a rapidly growing market.

As for 1NET wireless backhaul, ECI has announced one win so far - Israeli mobile operator Cellcom which has selected the 9000 CESR family. “Cellcom shows that ECI can continue to expand its presence in the network - in this case leveraging business Ethernet services to add backhaul,” says Hunt.

In addition one European operator, as yet unnamed, has selected ECI’s embedded overlay. “Several other operators are in various stages of selecting the right option for them,” says Ephstein.

- For some ECI wireless backhaul papers and case studies, click here

Ten years gone: Optical components after the boom

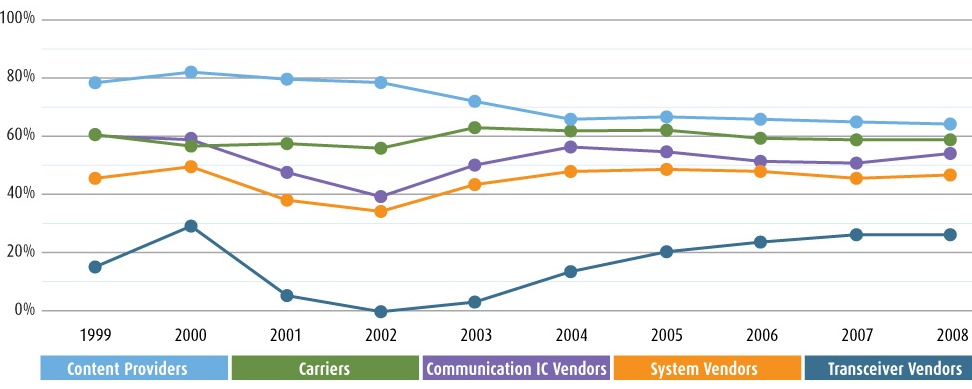

Average gross margin by industry. Source: LightCounting

Average gross margin by industry. Source: LightCounting

The biggest change in the last decade has been the way optics is perceived. That is the view of Vladimir Kozlov, boss of optical transceiver market research firm, LightCounting. “In 2000, optics was set to change the world,” he says. “The intelligent optical network would do all the work for the carrier; nothing would be done electrically.”

The boom of 1999-2000 saw hundreds of start-ups enter the market. Ten years on and a handful only remain; none changed the industry dramatically.

“The worse is definitely behind us”

“The worse is definitely behind us”

Vladimir Kozlov, LightCounting

Kozlov cites tunable lasers as an example. In 2000, the CEO of one start-up claimed the market for tunable lasers would grow to US$1 billion. Today the tunable laser market is worth several tens of millions. “It [the tunable laser] is a useful product that is selling but expectation didn’t match reality,” says Kozlov.

Another example is planar lightwave circuits used to make devices such as arrayed waveguide gratings used to multiplex and demultiplex wavelengths. “Intel was the biggest cheerleader,” says Kozlov. “Did planar lightwave circuits change the industry? No, but it is a useful technology.”

Where significant progress has been made is in the reliability, compactness and cost reduction of optical components. High-end lasers with complex control electronics have been replaced by small, single-chip devices that have minimal associated circuitry, says Kozlov.

Pragmatism not euphoria

The biggest surprise for Kozlov has been how many companies have survived the extremely tough market conditions. “There were almost no sales in 2001 and the market didn’t recover till 2004,” he says. Companies latched on to niche markets outside telecom to get by while many of the start-ups survived on their funding before folding, merging or being acquired by larger players.

“The leading companies such as Finisar, Excelight (now merged with Eudyna to form Sumitomo Electric Device Innovations), Avago Technologies and Opnext were also leading companies 10 years ago,” said Kozlov, who adds Oclaro, created with the merger of Bookham and Avanex.

The market has experienced hiccups since 2004 such as the dip of 2008-2009. “The worse is definitely behind us,” says Kozlov. Many vendors have a good vision as to what to do and plan accordingly. He notes companies are maintaining resources to be well placed to respond to rapid increases in demand. And profitability is rising sharply after the belt-tightening of 2008-09. “Whoever gets in first makes the profit,” says Kozlov. “That is what happened in 1999, although that was an extreme.”

Transceiver vendors and gross margins

Another notable development of the last decade has been the advent of optical transceivers. In the late 1990s system vendors such as Alcatel, Fujitsu, Marconi, NEC and Nortel designed their own optical systems before divesting their optical component arms. Optical component companies exploited the opportunity by developing optical transceivers to sell to the systems vendors.

LightCounting forecasts that the global optical transceiver market will total $2.2 billion in 2010, yet Kozlov still has doubts about the optical transceiver vendors’ business model. “Optical transceiver vendors still have to prove they are profitable and viable, that they are a real layer in the food chain.”

Comparing the gross margin performance of the industry layers that make up the telecom industry, optical transceiver vendors are last (see chart at the top of the page). Gross margin is an efficiency measure as to how well a vendor turns what they manufacture into income. Companies such as Cisco Systems have impressive gross margins of 75%. “You have to own a market, to have something unique to maintain such a margin,” says Kozlov.

Cisco has a unique position and to a degree so do semiconductors players which have gross margins twice those of the transceiver vendors. Contract manufacturers, however, have even lower margins than the 25% achieved by the transceiver vendors, adds Kozlov, but they benefit from large manufacturing volumes.

The main challenge for transceiver vendors is differentiating their products. There is also fierce competition across product segments. “A gross margin of 25% is not the end of the world as long as there are sufficient volumes,” says Kozlov. “And of course 25% in China is a lot – local [optical transceiver] vendors don’t think twice about entering the market.”

Kozlov says there are now between 20-30 Chinese optical transceiver vendors. “Some two thirds are benefiting from government funding but a third are building laser manufacturing and making transceivers, are real, and are here to stay.”

Bandwidth drives components

LightCounting collects quarterly shipment data from leading optical transceiver vendors worldwide. It also forecasts market demand based on a traffic model. Kozlov stresses the importance of the adoption of broadband schemes such as fibre-to-the-x (FTTx) as a traffic driver and ultimately transceiver sales.

A small change in the bandwidth utilisation of the access network has a huge impact on the network core. The advent of a killer application or the emergence of devices such as the iPhone and iPad that change user habits and drive access network utilisation from 2% to 5% would have a marked impact on operators’ networks. “This would require a significant upgrade and would result in a very nice bubble,” says Kozlov.

Utilised bandwidth (terabits-per-second). Scenario 2 with the higher utilisation in the access network quickly impacts core network capacity. Source: LightCounting

Utilised bandwidth (terabits-per-second). Scenario 2 with the higher utilisation in the access network quickly impacts core network capacity. Source: LightCounting

Another effect LightCounting has noted is that the total transceiver capacity is not keeping pace with growth in network traffic. This discrepancy is caused by operators running their networks more efficiently, explains Kozlov. Collapsing the number of platforms when operators adopt newer, more integrated systems is removing interfaces from the network.

LightCounting does not see operators’ traffic data such that Kozlov can’t know to what degrees operators are running their networks closer to capacity but given the rapid clip in traffic growth this is not a sustainable policy and hence does not explain this overall trend.

The next decade

Kozlov expects the next decade to continue like recent years with optical component companies being conservative and pragmatic. He is optimistic about optics’ adoption in the data centre as interface speeds move to 10Gbps and above, pushing copper to its limit. He also believes active optical cables are here to stay, while photonic integration will play an increasingly important role over time.

Kozlov also believes another bubble could occur especially if there is a need for more bandwidth at the network edge that will with a knock-on effect on the core.

But what gives him most optimism is that he simply doesn’t know. “We were all really wrong 10 years ago, maybe we will be again.”

- Lightwave July 2010: Interview with Vladimir Kozlov. "Can the optical transceiver industry sustain double-digit growth?

Ciena post-MEN

“The 40G and 100G technology were key to the deal and we made sure that the core team was still there”

Tom Mock, Ciena

The company has announced the CN 5150 service aggregation switch, added Nortel’s 40 Gigabit-per-seconds (Gbps) coherent transmission technology to its flagship CN 4200 platform, and announced 140 job cuts, mostly in Europe. US operator AT&T has also selected the company as one of two suppliers of its optical and transport equipment.

Ciena provides optical transport, optical switching and Carrier Ethernet equipment. “We were finding it difficult to fund the required R&D in all three segments,” says Tom Mock, senior vice president of strategic planning at Ciena. “We saw this [the MEN acquisition] as an opportunity to bring good technology on board and give the company the scale needed to execute in these technology areas.”

According to Mock, Ciena was one of several firms interested in the Nortel unit but that Nokia Siemens Networks was the main counter-bidder in the auction process. Ciena won after agreeing to pay US $773.8 million, gaining MEN’s R&D group and associated sales and marketing.

In particular, it gained the R&D for optical transport – Nortel’s Optical Multiservice Edge (OME) 6500 product line for 40Gbps and 100Gbps, the Optical Metro 5200 metro and enterprise platform, Carrier Ethernet, and the R&D for software and network management. Most of these activities are based in Ottawa, Ontario.

“We had pretty good solutions in optical switching and carrier Ethernet but we were looking for a stronger transport offering, which is what Nortel brought to us,” says Mock. The acquisition, which effectively doubles the company’s size, means that Ciena now plays in a “$18 billion sandbox” comprising optical networking and Ethernet transport and services, according to market research firm Ovum.

Did Ciena secure Nortel’s MEN’s key staff, given the lengthy period – over a year – to complete the acquisition? “We agreed with Nortel that we would get 2000 staff out of a total of 2300 staff,” says Mock.

Yet Ciena had no visibility regarding staff since Nortel remained a competitor until the deal was completed. “We were very pleasantly surprised at the quality of the people who were in MEN,” says Mock. “When companies are in hard times the best people begin to leave, and because of the uncertainty I’m sure some people did leave.”

Ciena claims it secured MEN’s core 40 and 100Gbps team despite announcements such as Infinera's that it had recruited John McNicol, a senior engineer involved in the development of Nortel’s coherent technology. “The 40G and 100G technology were key to the deal and we made sure that the core team was still there,” says Mock.

He also dismisses the view that Nortel’s 100Gbps coherent technology market lead has been eroded due to the uncertainty. Mock claims it has a 12- to 18-month lead and points to Verizon Business’ deployment of Nortel’s 100Gbps system in late 2009 as proof that MEN continued to push the technology.

Strategy

Ciena’s primary focus is on what it calls carrier optical Ethernet, described by Mock as the marrying of the capacity scaling and reliability of optical transport with the ubiquity, flexibility and economics of Ethernet.

For Ciena this translates to three main product lines:

- Packet optical transport, primarily optical transport with some aggregation.

- Packet optical switching based on Ciena’s CoreDirector platform with its time-division multiplexing (TDM) and Ethernet switching, as well as control plane technology.

- Carrier Ethernet service delivery.

According to Ovum, Ciena is now the third “billion dollar club” optical networking vendor member with a 9% market share, behind Huawei and Alcatel-Lucent, with 24% and 19%, respectively. It also becomes the North American leader, with a 20% share while improving its standing in all other regional markets. In contrast, for Ethernet the combined company had only 3% share in 2009. “We are emerging as a leader in the Carrier Ethernet space,” claims Mock. “In 4Q 2009 we were leading in North America, according to Heavy Reading.”

Ciena sees optical transport and switching blurring but says that most of its customers still see these as separate products. “Both our packet optical switching and packet optical transport platforms can be used in these applications, for example the OME 6500 is looked at as a transport device but it has TDM and packet switching as well,” says Mock. But with time Ciena says optical switching and optical transport product families will increasingly consolidate.

What next?

Having completed the deal, one of the first things Ciena did was determine its product portfolio and tell its operator customers its plans.

Issues set to preoccupy Ciena for the next 12 to 18 months include the integration of Nortel’s 40Gbps and 100Gbps technology onto Ciena’s transport and switching platforms, getting the control plane of Ciena’s switching product integrated onto Nortel’s products, and bringing all the products under common network management.

At OFC/ NFOEC 2010 Ciena showcased Nortel’s OME 6500 transmitting over Ciena’s CN 4200 line system with both being overseen by Ciena’s OnCenter management software. “I wouldn’t point to the network management integration as a finished product but a step along the path,” says Mock.

According to Ovum, the demonstrations included 100Gbps over 1,500km of Corning ultra-low-loss fiber, 100Gbps over 800km in the presence of large and fast polarisation mode dispersion transients, and 40Gbps ultra-long haul transmission over 3,500km.

Ciena has said it expects its business to grow at least at the market rate: 10 to 12 percent yearly.

AT&T domain supplier

In April, AT&T announced that it had selected Ciena as a domain supplier. AT&T's domain supplier programme involves the operator splitting its networking requirements across several technologies, choosing two players for each domain. AT&T plans to work closely with each domain supplier ensuring that AT&T gains equipment tailored to its requirements while vendors such as Ciena can focus their R&D spending by seeing early the operator’s roadmap.

Did Ciena acquire Nortel to become a domain partner? “We would not make an acquisition to win the business of any one carrier,” says Mock. “But we realised that if we going to be a significant player in next-generation infrastructure we needed a certain critical mass, in portfolio and market coverage globally.

“Did we get selected because of Nortel, it’s hard to say – I’m sure it didn’t hurt - but we've been a supplier to AT&T for 10 years,” says Mock. He also highlights the operator’s own announcement to explain Ciena’s selection: “They talk about two technologies in particular – 100Gbps technology and Optical Transport Networking (OTN).”

Ovum argues in its “Telecoms in 2020: network infrastructure” report that the future prospects of specialist vendors will be as rosy as full-service ones. “We do view ourselves as specialists even though we’ve essentially doubled the size of the company, and there is absolutely a place for specialist companies as they are genuinely more agile,” says Mock.

Mock also expects further system vendor consolidation. “Optical transport remains fragmented so there are opportunities for further consolidation,” he says. Fragmented in what way? “If you look at the router space there are two dominant players, in optical transport there are 10 – no-one has a 40 to 50 percent market share.”

Opnext's multiplexer IC plays its part in 100Gbps trial

AT&T’s 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) coherent trial between Louisiana and Florida detailed earlier this week was notable for several reasons. It included a mix of 10, 40 and 100Gbps wavelengths, Cisco Systems' newest IP core router, the CRS-3, and a 100Gbps line-side design from Opnext.

According to Andrew Schmitt, directing analyst of optical at Infonetics Research, what is significant about the 100Gbps AT&T trial is the real-time transmission; unlike previous 100Gbps trials no received data was block-captured and decoded offline.

Such real-time transmission required the use of Opnext’s 100Gbps coherent design comprising its silicon germanium (SiGe) multiplexer chip, announced in January, and an FPGA mock-up of the receiver circuitry.

"Several industry observers claim coherent detection is the most significant development since the advent of dense wavelength division multiplexing"

The multiplexer IC implements polarisation-multiplexing quadrature phase-shift keying (PM-QPSK) modulation (also known as dual-polarisation QPSK or DP-QPSK) at a line rate of up to 128Gbit/s, to accommodate advanced forward error correction (FEC) needed for 100Gbps transmission.

Yet despite the high speed electronics, the IC can be surface-mounted, simplifying packaging and assembly while reducing the cost of the 100Gbps transponder.

Why is the multiplexer IC important?

To enable the transition to 100Gbps optical transmission its economics needs to be improved. 100Gbps line-side MSA modules are needed to complement emerging IEEE 100 Gigabit Ethernet optical transceivers.

The Optical Internetworking Forum (OIF) backed by industry players have alighted on PM-QPSK as the chosen modulation approach for 100Gbps line-side interfaces. Operators such as AT&T and Verizon also back the technology for 100Gbps deployments.

Such industry recognition of coherent detection using PM-QPSK is based on the technological benefits already demonstrated at 40Gbps by Nortel. Indeed several industry observers claim coherent detection is the most significant development since the advent of dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM). While Verizon has stated that its next-generation links will be optimised for 100Gbps coherent transmission.

But developing 100Gbps technology is costly, which is why the OIF and operators are keen to focus the industry’s development R&D dollars on a single technological approach to avoid what has happened for 40Gbps transmission where four modulation schemes were developed and are still being deployed.

Opnext is the first company to detail a 100Gbps multiplexer chip. By operating at 128Gbit/s, the device supports the OIF’s 100Gbps ultra long haul DWDM Framework document yet the chip is packaged within a ball grid array to enable the use of surface-mount manufacturing on the printed circuit board. This avoids the expense and design complications associated with using radio frequency connectors.

The IC could also be used for 40Gbps PM-QPSK transponders. “We might have chosen CMOS [for a 40Gbps design] but there is no reason not to run it at a lower speed,” says Matt Traverso, senior manager, technical marketing at Opnext.

Method used

The multiplexer IC is manufactured using a 0.13 micron SiGe process. The in-house design has been developed by the engineering team Opnext acquired with the purchase of StrataLight.

Design work began a year ago. The resulting chip takes 10 channels, each at up to 11.3Gbit/s, and coverts the data to four 32Gbps channels that are then phase encoded. The multiplexer chip outputs are two polarisations, each comprising two 32Gbps I and Q data streams (see diagram). For a complete 100Gbps line-card diagram, showing the multiplexer IC, demultiplexer/ receiver ASIC that make up the line side and the client-side module, click here.

The input channel rate of 11.3Gbps is to support the Optical Transport Network (OTN) ODU-4 format while the 32Gbps per channel ensures that there is sufficient bit headroom for powerful forward error correction. It is the need to support 32Gbps data rates that required Opnext to use SiGe technology. “CMOS is good for 25 to 28Gbps rates; beyond that for good optical transport you need silicon germanium,” says Traverso.

The consensus however is that the industry will consolidate on CMOS for the multiplexer and demultiplexer/ receiver ICs. It could be that when Opnext defined its multiplexer design goals and timeline, CMOS was not an option.

How was the use of surface-mount technology (SMT) made possible? “The physical interface of the IC was designed based upon SMT packaging models to allow for sufficient margin in the jitter budget to achieve good transmission performance,” says Traverso. “The goal is to match the impedance over frequency from the chip contact through the packaging to the printed circuit board.”

Opnext has not said which foundry it is using to make the chip. Hitachi and IBM are obvious candidates but given Opnext’s history, Hitachi is most likely.

What next?

For 100Gbps line side transmission both multiplexing and demultiplexing circuitry are required. Opnext has detailed the multiplexing circuitry only.

At 100Gbps, the receiver circuitry requires the inverse demultiplexer circuitry – decoding the PM-QPSK signal and recovering the original 100Gbps (10x10Gbps) data. But also required are very high-speed analogue-to-digital converters (ADCs) along with a computationally powerful digital signal processor (DSP).

The ADC and DSP are used to recover the signal, compensating for chromatic and polarisation mode dispersions experienced during transmission. Given the channel data rate is 32Gbps, it implies that the ADCs are operating at 64 Gsample/s.

This is why developing such a chip is expensive and so technically challenging. “It requires finances, technical talent, significant optics expertise, integrated circuit knowledge, DSP design and ADC expertise,” says Traverso.

The reputed fee for developing such an ASIC is US $20m. Given there are at least four system vendors, Opnext, and two transponder/ chip players believed to be developing such an ASIC, this is a huge collective investment. But then the ASIC is where system vendors and transponder makers can differentiate their coherent-based products.

The ASIC also highlights the marked difference between Gigabit Ethernet (GbE) and line-side interfaces.

For 40 and 100GbE transceivers, interoperability between vendors’ transceivers is key. Long-haul connections, in contrast, tend to be proprietary. The industry may have alighted on a common modulation approach but paramount is optical performance. The ASIC, and the DSP and FEC algorithms it executes, is how vendor differentiation is achieved.

At OFC/NFOEC 2010 later this month working 100Gbps PM-QPSK modules are not expected. But it is likely that Opnext and others will detail their 100Gbps demultiplexing/ receiver ASICs. Meanwhile, coherent modules at 40Gbps are expected.

References

[1] “Performance of Dual-Polarization QPSK for Optical Transport Systems” by Kim Roberts et al, click here.

Jagdeep Singh's Infinera effect

Talking to gazettabyte, he reflects on the ups and downs of being a CEO, his love of running, 40 Gigabit transmission and why he is looking forward to his next role at Infinera.

"We are looking to lead the 40 Gig market, not be first to market.”

Jagdeep Singh, Infinera CEO

Ask Jagdeep Singh about how Infinera came about and there is no mistaking the enthusiasm and excitement in his voice.

During the bubble era of 2000 he started to question whether the push to all-optical networking pursued by numerous start-ups made sense. “The reason for these all-optical device companies was that they were developing the analogue functions needed,” says Singh. “Yet what operators really wanted was access to the [digital] bits.”

This led him to think about optical-to-electrical (O-E) conversion and the digital processing of signals to correct for transmission impairments. “The question then was: could this be done in a low-cost way?” says Singh. Achieving O-E conversion would also allow access to the bits for add/ drop, switching and grooming functions at the sub-wavelength level before using inverse electrical-to-optical (E-O) conversion to continue the optical transmission.

“We came at this from an orthogonal direction: building lower-cost O-E-O. Was it possible?” says Singh. “The answer was that most of the cost was in the packaging and that led us to think about photonic integration.”

Singh started out with his colleague Drew Perkins (now Infinera’s CTO) with whom he co-founded Lightera, a company acquired by Ciena in 1999. Then the two met with Dave Welch at a Christmas party in 2000. Welch had been CTO of SDL, a company just acquired by JDS Uniphase. “It was clear that he was not that happy and there were a lot of VCs (venture capitalists) chasing him,” says Singh. “He (Welch) recognised the power of what we were planning.” In January 2001 the three founded Infinera.

So why is he stepping down as CEO? The answer is to focus on long-term strategy. And perhaps to reclaim time outside work, given he has a young family.

He may even have more time for running.

Singh typically runs at least two marathons a year. “As a CEO your schedule is fully booked. There is so much stuff there is no time to think.” Running for him is quiet time. “I can get out and recharge the batteries. I find it invaluable. I can process things and it keeps the stress levels down.”

Being CEO

“There are two roles to being a CEO: running the business – the P&Ls (profit and loss statements), financials, sales – all real-time and urgent; and then there is the second part – setting the product vision: what products will be needed in two, three, four years’ time?” he says.

This second part is particularly important for Infinera given it develops products around its photonic integrated circuit (PIC) designs, requiring a longer development cycle than other optical equipment makers. “We have to get the requirements right up front,” says Singh.

And it is this part of the CEO’s role, he says, that gets trumped due to real-time tasks that must be addressed. Thus, from January, Singh will become Infinera’s executive chairman focussing exclusively on product planning. “If I had to choose [between the two roles], the longer term stuff is more appealing,” he says.

Looking back over his period as CEO, he believes his biggest achievement has been the team assembled at Infinera. “What I’ve learnt over the years is that the quality of success depends on the quality of the team.

“We started after the telecom bust,” says Singh. “There were world-class people that were never that locked in and [once on board] they knew people that they respected.” Now Infinera has a staff of 1,000, and had gone from a start-up to a publicly-listed company.

One downside of becoming a large company is that Singh regrets no longer personally knowing all his staff. “What I miss is that I knew everyone, I was part of a small team with a lot of energy,” he says. Another change is all the regulatory, legal and accounting that a public company must do. “I was also free to do and say what I wanted. Now I have to be a lot more careful.”

The Infinera effect

Asked about why Infinera is still not shipping a PIC with 40Gbps line rate channels, it is Singh-as-scrutinised-CEO that kicks in. “If we built 40 Gig purely using off-the-shelf components we’d have a product.” But he argues that the economics of 40 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) are still not compelling. According to market research firm Ovum, he says, it will only be 2012 when 40Gbps dips below four times the cost of 10Gbps.

Indeed in Q3 2009 shipments of 40Gbps slipped. According to Ovum, this was in part due to what it calls the “Infinera effect” that is lowering the cost of existing 10Gbps technology. Only when 40Gbps is around 2.5x the cost of 10Gbps that it is likely to take off; the economic rule-of-thumb with all previous optical speed hikes.

“Our goal is to come in with a 40 Gig solution that is economically viable,” says Singh. This is what Infinera is working on with its 10x40Gbps PIC pair of chips that integrate hundreds of optical functions. “With the PIC we are looking to lead the 40 Gig market, not be first to market.”

This year also saw Infinera introduce its second class of platform, the ATN, aimed at metro networks. The platform was developed across three Infinera sites: in Silicon Valley, India and China.

Coupled with Infinera’s DTN, the ATN allows end-to-end bandwidth management of its systems. “Until now we have only played in long-haul; this now doubles the market we play in,” says Infinera's CEO. Italian operator Tiscali announced in December 2009 its plan to deploy Infinera’s systems with the ATN being deployed in 80 metro locations.

How are cheap wavelength-selective switches and tunability impacting Infinera’s business? Singh bats away the question: “We just don’t see it in our space.”

Singh agrees with Infinera’s Dave Welch’s thesis that PICs are optics’ current disruption. What developments can he cite that will indicate this is indeed happening?

There are several examples that would confirm this, he says: “PICs in adjacent devices such as routers or switches; you would need something like a PIC to reduce the power and space of such platforms.” Other areas of adoption include connecting multiple bays such as required for the largest IP core routers, and even chip-to-chip interconnect.

Surely chip-to-chip is silicon photonics not Infinera’s PICs’ based on indium phosphide technology? Is silicon photonics of interest to Infinera?

"We are an optical transport company. To generate light over vast distances requires indium phosphide,” says Singh. “But if and when there is a breakthrough in silicon to generate light efficiently, we’d want to take advantage of that.”

One wonders what ideas Singh will come up with on his two-hour runs once he can think beyond the next financial quarter.