How scaling optical networks is soon to change

Carrier division multiplexing and spatial division multiplexing (CSDM) are both needed, argues Lumentum’s Brian Smith.

The era of coherent-based optical transmission as is implemented today is coming to an end, argues Lumentum in a White Paper.

Brian Smith

The author of the paper, Brian Smith, product and technology strategy, CTO Office at Lumentum, says two factors account for the looming change.

One is Shannon’s limit that defines how much information can be sent across a communications channel, in this case an optical fibre.

The second, less discussed regarding coherent-based optical transport, is how Moore’s law is slowing down.

”Both are happening coincidentally,” says Smith. “We believe what that means is that we, as an industry, are going to have to change how we scale capacity.”

Accommodating traffic growth

A common view in telecoms, based on years of reporting, is that internet traffic is growing 30 per cent annually. The CEO of AT&T mentioned over 30 per cent traffic growth in its network for the last three years during the company’s last quarterly report of 2023.

Smith says that data on the rate of traffic growth is limited. He points to a 2023 study by market research firm TeleGeography that shows traffic growth is dependent on region, ranging from 25 to 45 per cent CAGR.

Since the deployment of the first optical networking systems using coherent transmission in 2010, almost all networking capacity growth has been achieved in the C-band of a fibre, which comprises approximately 5 terahertz (THz) of spectrum.

Cramming more data into the C-band has come about by increasing the symbol rate used to transmit data and the modulation scheme used by the coherent transceivers, says Smith.

The current coherent era – labelled the 5th on the chart – is coming to an end. Source: Lumentum.

The current coherent era – labelled the 5th on the chart – is coming to an end. Source: Lumentum.

Pushing up baud rate

Because of the Shannon limit being approached, marginal gains exist to squeeze more data within the C-band. It means that more spectrum is required. In turn, the channel bandwidth occupied by an optical wavelength now goes up with baud rate such that while each wavelength carries more data, the capacity limit within the C-band has largely been reached.

Current systems use a symbol rate of 130-150 gigabaud (GBd). Later this year Ciena will introduce its 200GBd WaveLogic 6e coherent modem, while the industry has started work on developing the next generation 240-280GBd systems.

Reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexers (ROADMs) have had to become ‘flexible’ in the last decade to accommodate changing channel widths. For example, a 400-gigabit wavelength fits in a 75GHz channel while an 800-gigabit wavelength fits within a 150GHz channel.

Another consequence of Shannon’s limit is that the transmission distance limit for a certain modulation scheme has been reached. Using 16-ary quadrature amplitude modulation (16-QAM), the distance ranges from 800-1200km. Doubling the baud rate doubles the data rate per wavelength but the link span remains fixed.

“There is a fundamentally limit to the maximum reach that you can achieve with that modulation scheme because of the Shannon limit,” says Smith.

At the recent OFC show held in March in San Diego, a workshop discussed whether a capacity crunch was looming.

The session’s consensus was that, despite the challenges associated with the latest OIF 1600ZR and ZR+ standards, which promise to send 1.6 terabits of data on a single wavelength, the industry is confident that it will meet the OIF’s 240-280+ GBd symbol rates.

However, in the discussion about the next generation of baud rate—400-500GBd—the view is that while such rates look feasible, it is unclear how they will be achieved. The aim is always to double baud rate because the increase must be meaningful.

“If the industry can continue to push the baud rate, and get the cost-per-bit, power-per-bit, and performance required, that would be ideal,” says Smith.

But this is where the challenges of Moore’s law slowing down comes in. Achieving 240GBd and more will require a coherent digital signal processor (DSP) made using a 3nm CMOS process at least. Beyond this, transistors start to approach atomic scale and the performance becomes less deterministic. Moreover, the development costs of advanced CMOS processes – 3nm, 2nm and beyond – are growing exponentially.

Beyond 240GBd, it’s also going to become more challenging to achieve the higher analogue bandwidths for the electronics and optics components needed in a coherent modem, says Smith. How the components will be packaged is key. There is no point in optimising the analogue bandwidth of each component only for the modem performance to degrade due to packaging. “These are massive challenges,” says Smith.

This explains why the industry is starting to think about alternatives to increasing baud rate, such as moving to parallel carriers. Here a coherent modem would achieve a higher data rate by implementing multiple wavelengths per channel.

Lumentum refers to this approach as carrier division multiplexing.

Capacity scaling

The coherent modem, while key to optical transport systems, is only part of the scaling capacity story.

Prior to coherent optics, capacity growth was achieved by adding more and more wavelengths in the C-band. But with the advent of coherent DSPs compensating for chromatic and polarisation mode dispersion, suddenly baud rate could be increased.

“We’re starting to see the need, again, for growing spectrum,” says Smith. “But now, we’re growing spectrum outside the C-band.”

First signs of this are how optical transport systems are adding the L-band alongside the C-band, doubling a fibre’s spectrum from five to 10THz.

“The question we ask ourselves is: what happens once the C and L bands are exhausted?” says Smith.

Lumentum’s belief is that spatial division multiplexing will be needed to scale capacity further, starting with multiple fibre pairs. The challenge will be how to build systems so that costs don’t scale linearly with each added fibre pair.

There are already twin wavelength selective switches used for ROADMs for the C-band and L-bands. Lumentum is taking a first step in functional integration by combining the C- and L-bands in a single wavelength selective switch module, says Smith. “And we need to keep doing functional integration when we move to this new generation where spatial division multiplexing is going to be the approach.”

Another consideration is that, with higher baud-rate wavelengths, there will be far fewer channels per fibre. And with growing fibre pairs per route, that suggests a future need for fibre-switched networking not just wavelength switching networking as used today.

“Looking into the future, you may find that your individual routeable capacity is closer to a full C-band,” says Smith.

Will carrier division multiplexing happen before spatial division multiplexing?

Smith says that spatial division multiplexing will likely be first because Shannon’s limit is fundamental, and the industry is motivated to keep pushing Moore’s law and baud rate.

“With Shannon’s limit and with the expansion from C-band to C+L Band, if you’re growing at that nominal 30 per cent a year, a single fibre’s capacity will exhaust in two to three years’ time,” says Smith. “This is likely the first exhaust point.”

Meanwhile, even with carrier division multiplexing and the first parallel coherent modems after 240GBd, advancing baud rate will not stop. The jumps may diminish from the doublings the industry knows and that will continue for several years yet. But they will still be worth having.

Lumentum’s CTO discusses photonic trends

CTO interviews part 2: Brandon Collings

- The importance of moving to parallel channels will only increase given the continual growth in bandwidth.

- Lumentum’s integration of NeoPhotonics’ engineers and products has been completed.

- The use of coherent techniques continues to grow, which is why Lumentum acquired the telecom transmission product lines and staff of IPG Photonics.

“It has changed quite significantly given what Lumentum is engaging in,” he says. “My role spans the entire company; I’m engaged in a lot of areas well beyond communications.”

A decade ago, the main focus was telecom and datacom. Now Lumentum also addresses commercial lasers, 3D sensing, and, increasingly, automotive lidar.

Acquisitions

Lumentum was busy acquiring in 2022. The deal to buy NeoPhotonics closed last August. The month of August was also when Lumentum acquired IPG Photonics’ telecom transmission product lines, including its coherent digital signal processing (DSP) team.

NeoPhotonics’ narrow-linewidth tunable lasers complement Lumentum’s modulators and access tunable modules. Meanwhile, the two companies’ engineering teams and portfolios have now been merged.

NeoPhotonics was active in automotive lidar, but Lumentum stresses it has been tackling the market for several years.

“It’s an area with lots of nuances as to how it is going to be adopted: where, how fast and the cost dependences,” says Collings. “We have been supplying illuminators, VCSELs, narrow-linewidth lasers and other technologies into lidar solutions for several different companies.”

Lumentum gained a series of technological capabilities and some products with the IPG acquisition. “The big part was the DSP capability,” says Collings.

ROADMs

Telecom operators have been assessing IP-over-DWDM anew with the advent of coherent optical modules that plug directly into an IP router.

Cisco’s routed optical networking approach argues the economics of using routers and the IP layer for traffic steering rather than at the optical layer using reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexers (ROADMs).

Is Lumentum, a leading ROADM technology supplier, seeing such a change?

“I don’t think there is a sea change on the horizon of moving from optical to electrical switching,” says Collings. “The reason is still the same: transceivers are still more expensive than optical switches.”

That balance of when to switch traffic optically or electrically remains at play. Since IP traffic continues to grow, forcing a corresponding increase in signalling speed, savings remain using the optical domain.

“There will, of course, be IP routers in networks but will they take over ROADMs?” says Collings. “It doesn’t seem to be on the horizon because of this growth.”

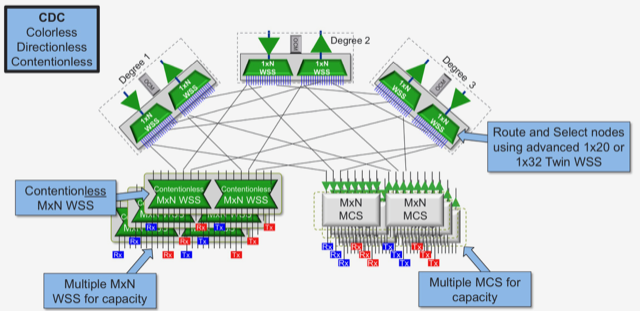

Meanwhile, the transition to more flexible optical networking using colourless, directionless, contentionless (CDC) ROADMs, is essentially complete.

Lumentum undertook four generations of switch platform design in the last decade to enable CDC-ROADM architectures that are now dominant, says Collings.

Lumentum moved from a simple add-drop to a route-and-select and a colourless, contentionless architecture.

A significant development was Lumentum’s adoption of liquid-crystal-on-silicon (LCOS) technology that enabled twin wavelength-selective switches (WSSes) per node that adds flexibility. LCOS also has enabled a flexible grid which Lumentum knew would be needed.

“We’re increasingly using MEMS technology alongside LCOS to do more complex switching functions embedded in colourless, directionless and contentionless networks today,” says Collings.

Shannon’s limit

If the last decade has been about enabling multiplexing and demultiplexing flexibility, the next challenge will be dealing with Shannon’s limit.

“We can’t stuff much more information into a single optical fibre – or that bit of the amplified spectrum of the optical fibre – and go the same distance,” says Collings. “We’ve sort of tapped out or reached that capacity.”

Adding more capacity requires amplified fibre bandwidth, such as using the L-band alongside the C-band or adding a second fibre.

Enabling such expansion in a cost- and power-efficient way will be fundamental, says Collings, and will define the next generation of optical networks.

Moreover, he expects consumer demand for bandwidth growth to continue. More sensing and more up-hauling of data to the cloud for processing will occur.

Accordingly, optical transceivers will continue to develop over the next decade.

“They are the complement requirement for scaling bandwidth, cost and power effectively,” he says.

Parallelism

Continual growth of bandwidth over the next decade will cause the industry to experience technological ceilings that will drive more parallelism in communications.

“If you look in data centres and datacom interconnects, they have long moved to parallel interface implementations because they felt that bandwidth ceiling from a technological, power dissipation or economic reason.”

Coherent systems have a symbol rate of 128 gigabaud (GBd), and the industry is working on 256GBd systems. Sooner or later, the consensus will be that the symbol rate is fast enough, and it is time to move to a parallel regime.

“In large-scale networks, parallelism is going to be the new thing over the next ten years,” says Collings.

Coherent technology

Collings segments the coherent optical market into three.

There are high-end coherent designs for long-haul transport developed by optical transport vendors such as Ciena, Cisco, Huawei, Infinera and Nokia.

Then there are designs such as 400ZR developed for data centre interconnect. Here a ‘pretty aggressive’ capability is needed but not full-scale performance.

At the lower end, there are application areas where direct-detect optics is reaching its limit. For example, inside the data centre, campus networks and access networks. Here the right solution is coherent or a ‘coherent-light’ technology that is a compromise between direct detection and full-scale coherence used for the long haul.

“So there is emerging this wide continuum of applications that need an equal continuum of coherent technology,” says Collings.

Now that Lumentum has a DSP capability with the IPG acquisition, it can engage with those applications that need solutions that use coherent but may not need the highest-end performance.

800 gigabits and 1.6 terabits

There is also an ongoing debate about the role of coherent for 800-gigabit and 1.6-terabit transceivers, and Collings says the issues remain unclear.

There’s a range of application requirements: 500m, 2km, and 10km. A direct-detect design may meet the 500m application but struggle at 2k and break down at 10km. “There’s a grey area, just in this simple example,” he says.

Also, the introduction of coherent should be nuanced; what is not needed is a long-haul 5,000km DSP. It is more a coherent-light solution or a borrowing from coherent technologies, says Collings: “You’re still trying to solve a problem that you can almost do with direct detect but not quite.”

The aim is to use the minimum needed to accomplish the goal because the design must avoid paying the cost and power to implement the full complement coherent long-haul.

“So that’s the other part of the grey area: how much you borrow?” he says. “And how much do you need to borrow if you’re dealing with 10km versus 2km, or 800 gigabits versus 1.6 terabits.”

Data centres are already using parallel solutions, so there is always the option to double a design through parallelism.

“Eight hundred gigabit could be the baseline with twice as many lanes as whatever we’re doing at 400 gigabits,” he says. “There is always this brute force approach that you need to best if you’re going to bring in new technologies.”

Optical interconnect

Another area Lumentum is active is addressing the issues of artificial intelligence machine-learning clusters. The machine-learning architectures used must scale at an unprecedented rate and use parallelism in processors, multiple such processors per cluster, and multiple clusters.

Scaling processors requires the scaling of their interconnect. This is driving a shift from copper to optics due to the bandwidth growth involved and the distances: 100, 200 and 400 gigabits and lengths of 30-50 meters, respectively.

The transition to an integrated optical interconnect capability will include VCSELs, co-packaged optics, and much denser optical connectivity to connect the graphic processing units (GPUs) rather than architectures based on pluggables that the industry is so familiar with, says Collings.

Co-packaged optics address a power dissipation interconnect challenge and will likely first be used for proprietary interconnect in very high density GPU artificial intelligence clusters.

Meanwhile, pluggable optics will continue to be used with Ethernet switches. The technology is mature and addresses the needs for at least two more generations.

“There’s an expectation that it’s not if but when the switchover happens to co-packaged optics and the Ethernet switch,” says Collings.

Material systems

Lumentum has expertise in several material systems, including indium phosphide, silicon photonics and gallium arsenide.

All these materials have strengths and weaknesses, he says.

Indium phosphide has bandwidth advantages and is best for light generation. Silicon is largely athermal, highly parallelisable and scalable. Staff joining from NeoPhotonics and IPG have strengthened Lumentum’s silicon photonics expertise.

“The question isn’t silicon photonics or indium phosphide. It’s how you get the best out of both material systems, sometimes in the same device,” says Collings. “Sticking in one sandbox is not going to be as competitive as being agile and having the ability to bring those sandboxes together.”

BT's IP-over-DWDM move

- BT will roll out next year IP-over-DWDM using pluggable coherent optics in its network

- At ECOC 2022, BT detailed network trials that involved the use of ZR+ and XR optics coherent pluggable modules

Telecom operators have been reassessing IP-over-DWDM with the advent of 400-gigabit coherent optics that plug directly into IP routers.

According to BT, using pluggables for IP-over-DWDM means a separate transponder box and associated ‘grey’ (short-reach) optics are no longer needed.

Until now, the transponder has linked the IP router to the dense wavelength-division multiplexing (DWDM) optical line system.

“Here is an opportunity to eliminate unnecessary equipment by putting coloured optics straight onto the router,” says Professor Andrew Lord, BT’s head of optical networking.

Removing equipment saves power and floor space too.

DWDM trends

Operators need to reduce the cost of sending traffic, the cost-per-bit, given the continual growth of IP traffic in their networks.

BT says its network traffic is growing at 30 per cent a year. As a result, the operator is starting to see the limits of its 100-gigabit deployments and says 400-gigabit wavelengths will be the next capacity hike.

Spectral efficiency is another DWDM issue. In the last 20 years, BT has increased capacity by lighting a new fibre pair using upgraded optical transport equipment.

Wavelength speeds have gone from 2.5 to 10, then to 40, 100, and soon 400 gigabits, each time increasing the total traffic sent over a fibre pair. But that is coming to an end, says BT.

“If you go to 1.2 terabits, it won’t go as far, so something has to give,” says Lord. ”So that is a new question we haven’t had to answer before, and we are looking into it.”

Fibre capacity is no longer increasing because coherent optical systems are already approaching the Shannon limit; send more data on a wavelength and it occupies a wider channel bandwidth.

Optical engineers have improved transmission speeds by using higher symbol rates. Effectively, this enables more data to be sent using the same modulation scheme. And keeping the same modulation scheme means existing reaches can still be met. However, upping the symbol rate is increasingly challenging.

Other ways of boosting capacity include making use of more spectral bands of a fibre: the C-band and the L-band, for example. BT is also researching spatial division multiplexing (SDM) schemes.

IP-over-DWDM

IP-over-DWDM is not a new topic, says BT. To date, IP-over-DWDM has required bespoke router coherent cards that take an entire chassis slot, or the use of coherent pluggable modules that are larger than standard QSFP-DD client-side optics ports.

“That would affect the port density of the router to the point where it’s not making the best use of your router chassis,“ says Paul Wright, optical research manager at BT Labs.

The advent of OIF-defined 400ZR optics has catalysed operators to reassess IP-over-DWDM.

The 400ZR standard was developed to link equipment housed in separate data centres up to 120km apart. The 120km reach is limiting for operators but BT’s interest in ZR optics stems from the promise of low-cost, high-volume 400-gigabit coherent optics.

“It [400ZR optics] doesn’t go very far, so it completely changes our architecture,” says Lord. “But then there’s a balance between the numbers of [router] hops and the cost reduction of these components.”

BT modelled different network architectures to understand the cost savings using coherent ZR and ZR+ optics; ZR+ pluggables have superior optical performance compared to 400ZR.

The networks modelled included IP routers in a hop-by-hop architecture where the optical layer is used for point-to-point links between the routers.

This worked well for traffic coming into a hub site but wasn’t effective when traffic growth occurred across the network, says Wright, since traffic cascaded through every hop.

BT also modelled ZR+ optics in a reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexer (ROADM) network architecture, as well as a hybrid arrangement using both ZR+ and traditional coherent optics. Traditional coherent optics, with its superior optical performance, can pass through a string of ROADM stages where ZR+ optics falls short.

BT compared the cost of the architectures assuming certain reaches for the various coherent optics and published the results in a paper presented at ECOC 2020. The study concluded that ZR and ZR+ optics offer significant cost savings compared to coherent transponders.

ZR+ pluggables have since improved, using higher output powers to better traverse a network’s ROADM stages. “The [latest] ZR+ optics should be able to go further than we predicted,” says Wright.

It means BT is now bought into IP-over-DWDM using pluggable optics.

BT is doing integration tests and plans to roll out the technology sometime next year, says Lord.

XR optics

BT is a member of the Open XR Forum, promoting coherent optics technology that uses optical sub-carriers.

Dubbed XR optics, if all the subs-carriers originate at the same point and are sent to a common destination, the technology implements a point-to-point communication scheme.

Sub-carrier technology also enables traffic aggregation. Each sub-carrier, or a group of sub-carriers, can be sent from separate edge-network locations to a hub where they are aggregated. For example, 16 endpoints, each using a 25-gigabit sub-carrier, can be aggregated at a hub using a 400-gigabit XR optics pluggable module. Here, XR optics is implementing point-to-multipoint communication.

Lord views XR optics as innovative. “If only we could find a way to use it, it could be very powerful,” he says. “But that is not a given; for some applications, XR optics might be too big and for others it may be slightly too small.”

ECOC 2022

BT’s Wright shared the results of recent trial work using ZR+ and XR optics at the recent ECOC 2022 conference, held in Basel in September.

The 400ZR+ were plugged into Nokia 7750 SR-s routers for an IP-over-DWDM trial that included the traffic being carried over a third-party ROADM system in BT’s network. BT showed the -10dBm launch-power ZR+ optics working over the ROADM link.

For Wright, the work confirms that 0dBm launch-power ZR+ optics will be important for network operators when used with ROADM infrastructures.

BT also trialled XR optics where traffic flows were aggregated.

“These emerging technologies [ZR+ and XR optics] open up for the first time the ability to deploy a full IP-over-DWDM solution,” concluded Wright.

Effect Photonics buys the coherent DSP team of Viasat

Effect Photonics has completed the acquisition of Viasat’s staff specialising in coherent digital signal processing and forward error correction (FEC) technologies and the associated intellectual property.

The company also announced a deal with Jabil Photonics – a business unit of manufacturing services firm Jabil – to co-develop coherent optical modules that the two companies will sell.

The deals enable Effect Photonics to combine Viasat’s coherent IP with its indium phosphide laser and photonic integrated circuit (PIC) expertise to build coherent optical designs and bring them to market.

Strategy

Harald Graber, chief commercial officer at Effect Photonics, says the company chose to target the coherent market after an internal strategic review about how best to use its PIC technology.

The company’s goal is to make coherent technology as affordable as possible to address existing and emerging markets.

“We have a kind of semiconductor play,” says Graber. By which he means high-volume manufacturing to make the technology accessible.

“When you go to low cost, you cannot depend 100 per cent on buying the coherent digital signal processor (DSP) from the merchant market,” he says. “So the idea was relatively early-born that somehow we had to address this topic.”

This led to talks with Viasat and the acquisition of its team and technology.

Markets

“We also saw, as with some of our competitors, that making modules for satellite or free-space optics has a natural harmony for the roadmaps,” says Graber.

Effect Photonics and Jabil Photonics will bring to market an advanced, low-power coherent module design based on the QSFP-DD form factor.

Graber says 400ZR+ coherent modules fall short in their output power which is noticeable for networks with multiple reconfigurable optical add/drop multiplexing (ROADM) stages.

“So you need a little more [output power], and our technology allows us to do more,” he says.

By owning a coherent DSP and PIC, the company can integrate closely the two to optimise the coherent engine’s optical performance.

“You have a lot of room for improvement, which you cannot do when you buy a merchant DSP, especially when we talk about a 1.6 terabit design and above,” says Graber. “Our optical machine is already fully integrated, including the laser. It’s just now this last piece part to alleviate the current industry barriers.”

Effect Photonics’ focus is the communications sector. “We are putting everything in place to serve the hyperscalers,” says Graber.

The company is also looking at satellite communications and free-space optics.

Effect Photonics is working with Aircision, a company developing a free-space optics system that can send 10 gigabit-per-second (Gbps) over a 5km link for mobile backhaul and broadband applications.

Having all the parts for coherent designs will enable the company to address other markets like quantum key distribution (QKD) and lidar.

“The main problem with QKD is you cannot use amplification,” says Graber. “You need to have something fully integrated, with a nice output power to achieve the links.”

Graber says that for QKD, the company will only have to tweak its chip.

“We just have to make sure that the internal noise is in the right levels and these kinds of things,” says Graber. “So there’s a lot of opportunities; it puts us in a nice position.”

Company

Effect Photonics is headquartered in The Netherlands and has offices in four countries.

Last year, the company raised $43M in Series-C funding. The company raised a further $20 million with the Viasat deal.

The company has 250 staff, split between engineering and a large manufacturing facility.

Lumentum ships a 400G CFP2-DCO coherent module

Lumentum has started supplying customers with its CFP2-DCO coherent optical module. Operators use the pluggable to add an optical transport capability to equipment.

The company describes the CFP2-DCO as a workhorse; a multi-purpose pluggable for interface requirements ranging from connecting equipment in separate data centres to long-haul optical transmission. The module works at 100-, 200-, 300- and 400-gigabit line rates.

The pluggable also complies with the OpenROADM multi-source agreement. It thus supports the open Forward Error Correction (oFEC) standard, enabling interoperability with oFEC-compliant coherent modules from other vendors.

“We are encountering a fundamental limit set by mother nature around spectral efficiency,”

“Optical communications is getting more diverse and dynamic with the inclusion of the internet content providers (ICPs) alongside traditional telecom operators,” says Brandon Collings, CTO at Lumentum.

The CFP2-DCO module is being adopted by traditional network equipment makers and by the ICPs who favour more open networking.

CFP2-DCOs modules from vendors support the OIF’s 400ZR standard that links switching and routing equipment in data centres up to 120km apart and more demanding custom optical transmission performance requirements, referred to as ZR+.

So what differentiates Lumentum’s CFP2-DCO from other coherent module makers?

Kevin Affolter, Lumentum’s vice president, strategic marketing for transmission, highlights the company’s experience in making coherent modules using the CFP form factor. Lumentum also makes the indium phosphide optical components used for its modules.

“We are by far the leading vendor of CFP2-ACO modules and that will go on for several years yet,” says Affolter.

Unlike the CFP2-DCO that integrates the optics and the digital signal processor (DSP), the earlier generation CFP2-ACO module includes optics only, with the coherent DSP residing on the line card.

The company also offers a 200-gigabit CFP2-DCO that has been shipping for over 18 months.

As a multi-purpose design, Affolter says some customers want to use the CFP2-DCO primarily at 200 gigabits for its long-haul reach while others want the improved performance of the proprietary 400-gigabit mode and its support of Ethernet and OTN clients.

“Each of the [merchant] DSPs has subtly different features,” says Affolter. “Some of those features are important to protect applications, especially for some of the hyperscalers’ applications.”

Higher baud rates

Lumentum did not make any announcements at the recent OFC virtual conference and show regarding indium phosphide-based coherent components operating at the next symbol rate of 128 gigabaud (GBd). But Collings says work continues in its lab: “This is a direction we are all headed.”

The latest coherent optical components operate at 100GBd, making possible 800-gigabit-per-wavelength transmissions. Moving to a 128GBd symbol rate enables a greater reach for the given transmission speed as well as the prospect of 1.2+ terabit wavelengths.

This means fewer coherent modules are needed to send a given traffic capacity, saving costs. But moving to a higher baud rate does not improve overall spectral density since a higher baud rate signal requires a wider channel.

“We are encountering a fundamental limit set by mother nature around spectral efficiency,” says Collings.

Optical transmission technology continues to follow the familiar formula where the more challenging high-end, high-performance coherent systems start as a line-card technology and then, as it matures, transitions to a more compact pluggable format. This trend will continue, says Collings.

The industry goal remains to scale capacity and reduce the dollars-per-bit cost and that applies to high-end line cards and pluggables. This will be achieved using greater integration and increasing the current baud rate.

“Getting capacity up, driving dollars-per-bit down is now what the game is going to be about for a while,” says Collings.

Whether the industry will go significantly above 128GBd such as 256GBd remains to be seen as this is seen as a technically highly challenging task.

However, the industry continues to demand higher network capacity and lower cost-per-bit. So Collings sees a couple of possible approaches to continue satisfying this demand.

The first is to keep driving down the cost of the 128GBd generations of transceivers, satisfying lower cost-per-bit and expanding capacity by using more and more transceivers.

The second approach is to develop transceivers that integrate multiple optical carriers into a single ‘channel’. A channel here refers to a unit of optical spectrum managed through the ROADM network. This would increase capacity per transceiver and lower the cost-per-bit.

“Both approaches are technical and implementation challenges and it remains to be seen which, or both, will be realised across the industry,” says Collings.

100-gigabit PAM-4 directly modulated laser

At OFC Lumentum announced that its 100-gigabit PAM-4 directly modulated laser (DML), which is being used for 500m applications, now supports the 2km-reach FR single-channel and FR4 four-channel client-side module standards.

This is a normal progression of client-side modules for the data centre where the higher performance externally-modulated laser (EML) for a datacom transceiver is the one paving the way. As the technology matures, the EML is replaced by a DML which is cheaper and has simpler drive and control circuitry.

“We started this [trait] with the -LR4 which was dominated by EMLs,” says Mike Staskus, vice president, product line management, datacom at Lumentum. “The fundamental cost savings of a DML is its smaller chip size, more chips per wafer, and fewer processes, fewer regrowths.”

The company is working on a 200-gigabit EML and a next-generation 100-gigabit DML that promises to be lower cost and possibly uncooled.

Reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexers (ROADMs)

Lumentum is working to expand its wavelength-selective switches (WSSes) to support the extended C-band, and C- and L-band options as a way to increase transmission capacity.

“We are expanding the overall ROADM portfolio to accommodate extended C-band and more efficient C-band and L-band opportunities to continue to build capacity into ROADM networks,” says Collings. “As spectral efficiency saturation sets in, we are going to need more amplified bandwidth and more fibres, and the C- and L-bands will double fibre capacity.”

The work includes colourless and directionless; colourless, directionless and contentionless, and higher-degree ROADM designs.

Lumentum on ROADM growth, ZR+, and 800G

CTO interview: Brandon Collings

- The ROADM market is experiencing a period of sustained growth

- The Open ROADM MSA continues to advance and expand its scope

- ZR+ coherent modules will support some interoperability to avoid becoming siloed but optical performance differentiation remains key

Lumentum reckons the ROADM growth started some 18-24 months ago.

Brandon Collings gave a Market Focus talk at the recent ECOC show in Dublin, where he explained why it is a good time to be in the reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexer (ROADM) business.

“Quantities are growing substantially and it is not one reason but a multitude of reasons,” says Collings. The CTO of Lumentum reckons the growth started some 18-24 months ago.

ROADM markets

Lumentum highlights three factors fuelling the demand for ROADM components.

The first is the emergence of markets such as China and India that previously did not use ROADMs.

“China has pretty universally adopted ROADMs going forward,” says Collings. Previously, Optical Transport Network (OTN) point-to-point links and large OTN switches have been used. But ongoing traffic growth means this solution alone is not sustainable, both in terms of the switch capacity and the number of optical transceivers required.

“The bandwidth needed for these OTN switches is scaling beyond the rational use of optical-electrical-optical (OEO) node configuration,” says Collings. “You need 50 to 300 terabits of OTN [switch capacity] surrounded by the equivalent amount of optical transceivers, and that is not economical.”

The Chinese service providers have adopted a hybrid ROADM and OTN network architecture. The ROADMs perform optical bypass – passing on lightpaths destined for other nodes in the network – to reduce the optical transceivers and OTN switch capacity needed.

The network operators in India, in contrast, are using ROADMs to cope with the many fibre cuts they experience. The ROADMs are used to restore the network by rerouting traffic around the faults.

A second market magnifier is how modern ROADM networks use more wavelength-selective switches (WSSes). Both colourless and directionless (CD) ROADMs, and colourless, directionless and contentionless (CDC) ROADMs use more WSSes per node (see diagram above).

Such ROADMs also use more advanced WSS designs. Using an MxN WSS for the multicast switch in a route-and-select CDC ROADM, for example, delivers system benefits especially when adding and dropping wider optical channels that are starting to be used. Collings says Lumentum’s own MxN WSS is now close to volume manufacturing.

The third factor fuelling ROADM growth is the ongoing demand for more capacity. “Every time you fill a fibre, you typically use another degree in your [ROADM] node and light up a second fibre to grow capacity,” says Collings.

Operators with limited fibre are exploiting the fibre’s spectrum by using the C-band and L-band to grow capacity. This, too, requires more WSSes per node.

“All of these growth factors are happening simultaneously,” says Collings.

Open ROADM MSA

Lumentum is also a member of the Open ROADM multi-source agreement (MSA) that has created a disaggregated design to enable interoperability between systems vendors’ ROADMs.

AT&T is deploying Open ROADM systems in its metro networks while the MSA members have begun work on Revision 6.0 of the standard.

“Open ROADM is maturing and increasing its span of interest,” says Collings.

At first glance, Lumentum’s membership is surprising given it supplies ROADM building-blocks to vendors that make the ROADM systems. Moreover, the Open ROADM standard views a ROADM as an enclosed system.

“The Open ROADM has set certain boundaries where it defines interfaces so that vendor A can talk to vendor B,” says Collings. “And it has set that boundary pretty much at the complete ROADM node.”

Yet Lumentum is an MSA member because part of the software involved in controlling the ROADM is within the node. “It is not just a hardware solution, it is hardware and a significant software solution to supply into that,” says Collings.

Pluggable optics is also a part of the Open ROADM MSA, another reason for Lumentum’s interest. “There is a general discussion about potentially making a boundary condition around pluggable optics as well,” he says.

Collings says the MSA continues to build the ecosystem and the management system to help others use Open ROADM, not just AT&T.

400ZR, OpenZR+ and ZR+

As a supplier of coherent optics and line-side modules, Lumentum is interested in the OIF’s 400ZR standard and what is referred to as ZR+.

ZR+ offers an extended set of features and enhance optical performance. Both 400ZR and ZR+ will be implemented using QSFP-DD and OSFP pluggable modules.

The 400ZR specification has been developed for a specific purpose: to deliver 400 Gigabit Ethernet for distances of at least 80km for data centre interconnect applications. But 400ZR is not suited for more demanding metro mesh and longer-distance metro-regional applications.

This is what ZR+ aims to address. However, ZR+, unlike 400ZR, is not a standard and is a broad term.

At ECOC, Acacia Communications and NTT Electronics detailed interoperability between their coherent DSPs using what they call ‘OpenZR+’. OpenZR+ uses Ethernet traffic like 400ZR but also supports the additional data rates of 100, 200 and 300 Gigabit Ethernet. OpenZR+ also borrows from the OpenROADM specification to enable module interoperability between vendors for data centre interconnect applications with reaches beyond 120km.

But ZR+ encompasses differentiated coherent designs that support 400 gigabits in a compact pluggable but also lower transmission rates that trade capacity for reach.

“So, yes, both classes of ‘ZR+’ are emerging,” says Collings.

OpenZR+ seeks interoperability in compact pluggables, as well as higher power, higher performance modes less focused on interoperability, while ZR+ includes proprietary, higher-power solutions. “That [ZR+] is an area where distance and capacity equal money, in terms of savings and value,” says Collings. “That is going to be an area of differentiation, as it has always been for coherent interfaces.”

Collings favours some standardisation around ZR+, to enable interchangeability among module vendors and avoid the creation of a siloed market.

“But I don’t think we are going to find ZR+ interfaces defined for interoperability because you will find yourself walking back on that differentiation in terms of value that the network operators are looking to extract,” says Collings. “They need every bit of distance they can get.”

Network operators want compact, cost-effective solutions that do ‘even more stuff’ than they are used to. “400ZR checks that box but for bigger, broader networks, operators want the same thing,” says Collings.

There is a continuum of possibilities here, he says: “It is high value from a network operator point of view and it’s a technology challenge for the likes of us and the [DSP] chip vendors.”

800G Pluggable MSA

Lumentum also recently joined the 800G Pluggable MSA that was announced at the CIOE show, held in Shenzhen in September.

“Like any client interface where Lumentum is a supplier of the underlying [laser] chips – whether DMLs, EMLs or VCSELs – we feel it is pretty important for us to be in the definition setting of the interface,” says Collings. “We want the interface to be aligned optimally to what the chip can do.”

Lumentum announced last year that it is exiting the client-side module business and therefore will be less involved in the module aspects of the interface work.

“Having moved out of the [client-side] module business, we’re finding an awful lot of customers interested in engaging with us on the chip level, much more than before,” says Collings.

Further information

For an Optical Connections article about OpenZR+, co-authored by Acacia, NTT Electronics, Lumentum, Juniper Networks and Fujitsu Optical Components, click here

Will white boxes predominate in telecom networks?

Will future operator networks be built using software, servers and white boxes or will traditional systems vendors with years of network integration and differentiation expertise continue to be needed?

AT&T’s announcement that it will deploy 60,000 white boxes as part of its rollout of 5G in the U.S. is a clear move to break away from the operator pack.

The service provider has long championed network transformation, moving from proprietary hardware and software to a software-controlled network based on virtual network functions running on servers and software-defined networking (SDN) for the control switches and routers.

Glenn WellbrockNow, AT&T is going a stage further by embracing open hardware platforms - white boxes - to replace traditional telecom hardware used for data-path tasks that are beyond the capabilities of software on servers.

Glenn WellbrockNow, AT&T is going a stage further by embracing open hardware platforms - white boxes - to replace traditional telecom hardware used for data-path tasks that are beyond the capabilities of software on servers.

For the 5G deployment, AT&T will, over several years, replace traditional routers at cell and tower sites with white boxes, built using open standards and merchant silicon.

“White box represents a radical realignment of the traditional service provider model,” says Andre Fuetsch, chief technology officer and president, AT&T Labs. “We’re no longer constrained by the capabilities of proprietary silicon and feature roadmaps of traditional vendors.”

But other operators have reservations about white boxes. “We are all for open source and open [platforms],” says Glenn Wellbrock, director, optical transport network - architecture, design and planning at Verizon. “But it can’t just be open, it has to be open and standardised.”

Wellbrock also highlights the challenge of managing networks built using white boxes from multiple vendors. Who will be responsible for their integration or if a fault occurs? These are concerns SK Telecom has expressed regarding the virtualisation of the radio access network (RAN), as reported by Light Reading.

“These are the things we need to resolve in order to make this valuable to the industry,” says Wellbrock. “And if we don’t, why are we spending so much time and effort on this?”

Gilles Garcia, communications business lead director at programmable device company, Xilinx, says the systems vendors and operators he talks to still seek functionalities that today’s white boxes cannot deliver. “That’s because there are no off-the-shelf chips doing it all,” says Garcia.

We’re no longer constrained by the capabilities of proprietary silicon and feature roadmaps of traditional vendors

White boxes

AT&T defines a white box as an open hardware platform that is not made by an original equipment manufacturer (OEM).

A white box is a sparse design, built using commercial off-the-shelf hardware and merchant silicon, typically a fast router or switch chip, on which runs an operating system. The platform usually takes the form of a pizza box which can be stacked for scaling, while application programming interfaces (APIs) are used for software to control and manage the platform.

As AT&T’s Fuetsch explains, white boxes deliver several advantages. By using open hardware specifications for white boxes, they can be made by a wider community of manufacturers, shortening hardware design cycles. And using open-source software to run on such platforms ensures rapid software upgrades.

Disaggregation can also be part of an open hardware design. Here, different elements are combined to build the system. The elements may come from a single vendor such that the platform allows the operator to mix and match the functions needed. But the full potential of disaggregation comes from an open system that can be built using elements from different vendors. This promises cost reductions but requires integration, and operators do not want the responsibility and cost of both integrating the elements to build an open system and integrating the many systems from various vendors.

Meanwhile, in AT&T’s case, it plans to orchestrate its white boxes using the Open Networking Automation Platform (ONAP) - the ‘operating system’ for its entire network made up of millions of lines of code.

ONAP is an open software initiative, managed by The Linux Foundation, that was created by merging a large portion of AT&T’s original ECOMP software developed to power its software-defined network and the OPEN-Orchestrator (OPEN-O) project, set up by several companies including China Mobile and China Telecom.

AT&T has also launched several initiatives to spur white-box adoption. One is an open operating system for white boxes, known as the dedicated network operator system (dNOS). This too will be passed to The Linux Foundation.

The operator is also a key driver of the open-based reconfigurable optical add/ drop multiplexer multi-source agreement, the OpenROADM MSA. Recently, the operator announced it will roll out OpenROADM hardware across its network. AT&T has also unveiled the Akraino open source project, again under the auspices of the Linux Foundation, to develop edge computing-based infrastructure.

At the recent OFC show, AT&T said it would limit its white box deployments in 2018 as issues are still to be resolved but that come 2019, white boxes will form its main platform deployments.

Xilinx highlights how certain data intensive tasks - in-line security, performed on a per-flow basis, routing exceptions, telemetry data, and deep packet inspection - are beyond the capabilities of white boxes. “White boxes will have their place in the network but there will be a requirement, somewhere else in the network for something else, to do what the white boxes are missing,” says Garcia.

Transport has been so bare-bones for so long, there isn’t room to get that kind of cost reduction

AT&T also said at OFC that it expects considerable capital expenditure cost savings - as much as a halving - using white boxes and talked about adopting in future reverse auctioning each quarter to buy its equipment.

Niall Robinson, vice president, global business development at ADVA Optical Networking, questions where such cost savings will come from: “Transport has been so bare-bones for so long, there isn’t room to get that kind of cost reduction. He also says that there are markets that already use reverse auctioning but typically it is for items such as components. “For a carrier the size of AT&T to be talking about that, that is a big shift,” says Robinson.

Layer optimisation

Verizon’s Wellbrock first aired reservations about open hardware at Lightwave’s Open Optical Conference last November.

In his talk, Wellbrock detailed the complexity of Verizon’s wide area network (WAN) that encompasses several network layers. At layer-0 are the optical line systems - terminal and transmission equipment - onto which the various layers are added: layer-1 Optical Transport Network (OTN), layer-2 Ethernet and layer-2.5 Multiprotocol Label Switching (MPLS). According to Verizon, the WAN takes years to design and a decade to fully exploit the fibre.

“You get a significant saving - total cost of ownership - from combining the layers,” says Wellbrock. “By collapsing those functions into one platform, there is a very real saving.” But there is a tradeoff: encapsulating the various layers’ functions into one box makes it more complex.

“The way to get round that complexity is going to a Cisco, a Ciena, or a Fujitsu and saying: ‘Please help us with this problem’,” says Wellbrock. “We will buy all these individual piece-parts from you but you have got to help us build this very complex, dynamic network and make it work for a decade.”

Next-generation metro

Verizon has over 4,000 nodes in its network, each one deploying at least one ROADM - a Coriant 7100 packet optical transport system or a Fujitsu Flashwave 9500. Certain nodes employ more than one ROADM; once one is filled, a second is added.

“Verizon was the first to take advantage of ROADMs and we have grown that network to a very large scale,” says Wellbrock.

The operator is now upgrading the nodes using more sophiticated ROADMs, as part of its next-generation metro. Now each node will need only one ROADM that can be scaled. In 2017, Verizon started to ramp and upgraded several hundred ROADM nodes and this year it says it will hit its stride before completing the upgrades in 2019.

“We need a lot of automation and software control to hide the complexity of what we have built,” says Wellbrock. This is part of Verizon’s own network transformation project. Instead of engineers and operational groups in charge of particular network layers and overseeing pockets of the network - each pocket being a ‘domain’, Verizon is moving to a system where all the networks layers, including ROADMs, are managed and orchestrated using a single system.

The resulting software-defined network comprises a ‘domain controller’ that handles the lower layers within a domain and an automation system that co-ordinates between domains.

“Going forward, all of the network will be dynamic and in order to take advantage of that, we have to have analytics and automation,” says Wellbrock.

In this new world, there are lots of right answers and you have to figure what the best one is

Open design is an important element here, he says, but the bigger return comes from analytics and automation of the layers and from the equipment.

This is why Wellbrock questions what white boxes will bring: “What are we getting that is brand new? What are we doing that we can’t do today?”

He points out that the building blocks for ROADMs - the wavelength-selective switches and multicast switches - originate from the same sub-system vendors, such that the cost points are the same whether a white box or a system vendor’s platform is used. And using white boxes does nothing to make the growing network complexity go away, he says.

“Mixing your suppliers may avoid vendor lock-in,” says Wellbrock. “But what we are saying is vendor lock-in is not as serious as managing the complexity of these intelligent networks.”

Wellbrock admits that network transformation with its use of analytics and orchestration poses new challenges. “I loved the old world - it was physics and therefore there was a wrong and a right answer; hardware, physics and fibre and you can work towards the right answer,” he says. “In this new world, there are lots of right answers and you have to figure what the best one is.”

Evolution

If white boxes can’t perform all the data-intensive tasks, then they will have to be performed elsewhere. This could take the form of accelerator cards for servers using devices such as Xilinx’s FPGAs.

Adding such functionality to the white box, however, is not straightforward. “This is the dichotomy the white box designers are struggling to address,” says Garcia. A white box is light and simple so adding extra functionality requires customisation of its operating system to run these application. And this runs counter to the white box concept, he says.

We will see more and more functionalities that were not planned for the white box that customers will realise are mandatory to have

But this is just what he is seeing from traditional systems vendors developing designs that are bringing differentiation to their platforms to counter the white-box trend.

One recent example that fits this description is Ciena’s two-rack-unit 8180 coherent network platform. The 8180 has a 6.4-terabit packet fabric, supports 100-gigabit and 400-gigabit client-side interfaces and can be used solely as a switch or, more typically, as a transport platform with client-side and coherent line-side interfaces.

The 8180 is not a white box but has a suite of open APIs and has a higher specification than the Voyager and Cassini white-box platforms developed by the Telecom Infra Project.

“We are going through a set of white-box evolutions,” says Garcia. “We will see more and more functionalities that were not planned for the white box that customers will realise are mandatory to have.”

Whether FPGAs will find their way into white boxes, Garcia will not say. What he will say is that Xilinx is engaged with some of these players to have a good view as to what is required and by when.

It appears inevitable that white boxes will become more capable, to handle more and more of the data-plane tasks, and as a response to the competition from traditional system vendors with their more sophisticated designs.

AT&T’s white-box vision is clear. What is less certain is whether the rest of the operator pack will move to close the gap.

ON2020 rallies industry to address networking concerns

Source: ON2020

Source: ON2020

The slide shows how router-blade client interfaces are scaling at 40% annually compared to the 20% growth rate of general single-wavelength interfaces (see chart).

Extrapolating the trend to 2024, router blades will support 20 terabits while client interfaces will only be at one terabit. Each blade will thus require 20 one-terabit Ethernet interfaces. “That is science fiction if you go off today’s technology,” says Winzer, director of optical transmission subsystems research at Nokia Bell Labs and a member of the ON2020 steering committee.

This is where ON2020 comes in, he says, to flag up such disparities and focus industry efforts so they are addressed.

ON2020

Established in 2016, the companies driving ON2020 are Fujitsu, Huawei, Nokia, Finisar, and Lumentum.

The reference to 2020 signifies how the group looks ahead four to five years, while the name is also a play on 20/20 vision, says Brandon Collings, CTO of Lumentum and also a member of the steering committee.

Brandon CollingsON2020 addresses a void in the industry, says Collings. The Optical Internetworking Forum (OIF) organisation may have a similar conceptual mission but it is more hands-on, focussing on components and near-term implementations. ON2020 looks further out.

“Maybe you could argue it is a two-step process,” says Collings. “First, ON2020 is longer term followed by the OIF’s definition in the near term.”

To build a longer-term view, ON2020 surveyed network operators worldwide including the largest internet content providers players and leading communications service providers.

ON2020 reported its findings at the recent ECOC show under three broad headings: traffic growth and the impact on fibre capacity and interfaces, interconnect requirements, and network management and operations.

Things will have to get cheaper; that is the way things are.

Network management

One key survey finding is the importance network operators attach to software-defined networking (SDN) although the operators are frustrated with the lack of SDN solutions available, forcing them to work with vendors to address their needs.

Peter WinzerThe network operators also see value in white boxes and disaggregation, to lower hardware costs and avoid vendor lock-in. But as with SDN, there are challenges with white boxes and disaggregation.

“Let’s not forget that SDN comes from the big webscales,” says Winzer, companies with abundant software and control experience. Telecom companies don’t have such sophisticated resources.

“This produces a big conundrum for the telecom operators: they want to get the benefits without spending what the webscales are spending,” says Winzer. The telcos also need higher network reliability such that their job is even harder.

Responding to ON2020’s anonymous survey, the telecom players stress how SDN, disaggregation and the adoption of white boxes will require a change in practices and internal organisation and even the employment of system integrators.

“They are really honest. They say, nice, but we are just overwhelmed,” says Winzer. “It highlights the very important organisational challenges operators are facing.”

Operators are frustrated with the lack of SDN solutions available.

Capacity and connectivity

The webscales and telecom operators were also surveyed about capacity and connectivity issues.

Both classes of operator use 10-terabit links or more and this will soon rise to 40 terabits. The consensus is that the C-band alone is insufficient given their capacity needs.

Those operators with limited fibre want to grow capacity by also using the L-band with the C-band, while operators with plenty of fibre want to combine fibre pairs - a form of spatial division multiplexing - and using the C and L bands. The implication here is that there is an opportunity for hardware integration, says ON2020.

Network operators use backbone wavelengths at 100, 200 and 400 gigabits. As for service feeds - what ON2020 refers to as granularity - webscale players favour 25 gigabit-per-second (Gbps) whereas telecom operators continue to deal with much slower feeds - 10Mbps, 100Mbps, and 1Gbps.

What can ON2020 do to address the demanding client-interface requirements of IP router blades, referred to in the chart?

Xiang Liu, distinguished scientist, transmission product line at Huawei and a key instigator in the creation of ON2020, says photonic integration and a tighter coupling between photonics and CMOS will be essential to reduce the cost-per-bit and power-per-bit of future client interfaces.

Xiang Liu

Xiang Liu

“As the investment for developing routers with such throughputs could be unprecedentedly high, it makes sense for our industry to collectively define the specifications and interfaces,” says Liu. “ON2020 can facilitate such an industry-wide effort.”

Another survey finding is that network operators favour super-channels once client interfaces reach 400 gigabits and higher rates. Super-channels are more efficient in their use of the fibre’s spectrum while also delivering operations, administration, and management (OAM) benefits.

The network operators were also asked about their node connectivity needs. While they welcome the features of advanced reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexers (ROADMs), they don’t necessarily need them all. A typical response being they will adopt such features if they are practically for free.

This, says Winzer, is typical of carriers. “Things will have to get cheaper; that is the way things are.”

Photonic integration and a tighter coupling between photonics and CMOS will be essential to reduce the cost-per-bit and power-per-bit of future client interfaces

Future plans

ON2020 is still seeking feedback from additional network operators, the survey questionnaire being availability for download on its website. “The more anonymous input we get, the better the results will be,” says Winzer.

Huawei’s Liu says the published findings are just the start of the group’s activities.

ON2020 will conduct in-depth studies on such topics as next-generation ROADM and optical cross-connects; transport SDN for resource optimisation and multi-vendor interoperability; 5G-oriented optical networking that delivers low latency, accurate synchronisation and network slicing; new wavelength-division multiplexing line rates beyond 200 gigabit; and optical link technologies beyond just the C-band and new fibre types.

ON2020 will publish a series of white papers to stimulate and guide the industry, says Liu.

The group also plans to provide input to standardisation organisations to enhance existing standards and start new ones, create proof-of-concept technology demonstrators, and enable multi-vendor interoperable tests and field trials.

Discussions have started for ON2020 to become an IEEE Industry Connections programme. “We don’t want this to be an exclusive club of five [companies],” says Winzer. “We want broad participation.”

OFC 2015 digest: Part 1

- Several vendors announced CFP2 analogue coherent optics

- 5x7-inch coherent MSAs: from 40 Gig submarine and ultra-long haul to 400 Gig metro

- Dual micro-ITLAs, dual modulators and dual ICRs as vendors prepare for 400 Gig

- WDM-PON demonstration from ADVA Optical Networking and Oclaro

- More compact and modular ROADM building blocks

JDSU also showed a dual-carrier coherent lithium niobate modulator capable of 400 Gig for long-reach applications. The company is also sampling a dual 100 Gig micro-ICR also for multiple sub-channel applications.

Avago announced a micro-ITLA device using its external cavity laser that has a line-width less than 100kHz. The micro-ITLA is suited for 100 Gig PM-QPSK and 200 Gig 16-QAM modulation formats and supports a flex-grid or gridless architecture.

OIF prepares for virtual network services

The Optical Internetworking Forum has begun specification work for virtual network services (VNS) that will enable customers of telcos to define their own networks. VNS will enable a user to define a multi-layer network (layer-1 and layer-2, for now) more flexibly than existing schemes such as virtual private networks.

Vishnu Shukla"Here, we are talking about service, and a simple way to describe it [VNS] is network slicing," says OIF president, Vishnu Shukla. "With transport SDN [software-defined networking], such value-added services become available."

Vishnu Shukla"Here, we are talking about service, and a simple way to describe it [VNS] is network slicing," says OIF president, Vishnu Shukla. "With transport SDN [software-defined networking], such value-added services become available."

The OIF work will identify what carriers and system vendors must do to implement VNS. Shukla says the OIF already has experience working across multiple networking layers, and is undertaking transport SDN work. "VNS is a really valuable extension of the transport SDN work," says Shukla.

The OIF expects to complete its VNS Implementation Agreement work by year-end 2015.

Meanwhile, the OIF's Carrier Working Group has published its recommendations document, entitled OIF Carrier WG Requirements for Intermediate Reach 100G DWDM for Metro Type Applications, that provides input for the OIF's Physical Link Layer (PLL) Working Group.

The PLL Working Group is defining the requirements needed for a compact, low-cost and low-power 100 Gig interface for metro and regional networks. This is similar to the OIF work that successfully defined the first 100 Gig coherent modules in a 5x7-inch MSA.

The Carrier Working Group report highlights key metro issues facing operators. One is the rapid growth of metro traffic which, according to Cisco Systems, will surpass long-haul traffic in 2014. Another is the change metro networks are undergoing. The metro is moving from a traditional ring to a mesh architecture with the increasing use of reconfigurable optical add/drop multiplexers (ROADMs). As a result, optical wavelengths have further to travel, must contend with passing through more ROADMs stages and more fibre-induced signal impairments.

Shukla stresses there are differences among operators as to what is considered a metro network. For example, metro networks in North America span 400-600km typically and can be as much as 1,000km. In Europe such spans are considered regional or even long-haul networks. Metro networks also vary greatly in their characteristics. "Because of these variations, the requirements on optical modules varies so much, from unit to unit and area to area," says Shukla.

Given these challenges, operators want a module with sufficient optical performance to contend with the ROADM stages, and variable distances and network conditions encountered. "Sometimes we feel that the requirements [between metro and long-haul] won't be that much [different]," says Shukla. Indeed, the Carrier Working Group report discusses how the boundaries between metro and long-haul networks are blurring.

Yet operators also want such robust optical module performance at a greatly reduced price. One of the report's listed requirements is the need for the 100 Gig intermediate-reach interfaces to cost 'significantly' less than the cheapest long-haul 100 Gig.

To this aim, the report recommends that the 100 Gig pluggable optical modules such as the CFP or CFP2 be used. Standardising on industry-accepted pluggable MSAs will drive down cost as happened with the introduction of 100 Gig long haul 5x7-inch MSA modules.

Metro and regional coherent interfaces will also allow the specifications to be relaxed in terms of the DSP-ASIC requirements and the modulation schemes used. "When we come to the metro area, chances are that some of the technologies can be done more simply, and the cost will go down," says Shukla. Using pluggables will also increase 100 Gig line card densities, further reducing cost, while the report also favours the DSP-ASIC being integrated into the pluggable module, where possible.

Contributors to the Carrier Working Group report include representatives from China Telecom, Deutsche Telekom, Orange, Telus and Verizon, as well as module maker Acacia.