Optical networking: The next 10 years

Predicting the future is a foolhardy endeavour, at best one can make educated guesses.

Ioannis Tomkos is better placed than most to comment on the future course of optical networking. Tomkos, a Fellow of the OSA and the IET at the Athens Information Technology Centre (AIT), is involved in several European research projects that are tackling head-on the challenges set to keep optical engineers busy for the next decade.

“We are reaching the total capacity limit of deployed single-mode, single-core fibre,” says Tomkos. “We can’t just scale capacity because there are limits now to the capacity of point-to-point connections.”

Source: Infinera

Source: Infinera

The industry consensus is to develop flexible optical networking techniques that make best use of the existing deployed fibre. These techniques include using spectral super-channels, moving to a flexible grid, and introducing ‘sliceable’ transponders whose total capacity can be split and sent to different locations based on the traffic requirements.

Once these flexible networking techniques have exhausted the last Hertz of a fibre’s C-band, additional spectral bands of the fibre will likely be exploited such as the L-band and S-band.

After that, spatial-division multiplexing (SDM) of transmission systems will be used, first using already deployed single-mode fibre and then new types of optical transmission systems that use SDM within the same optical fibre. For this, operators will need to put novel fibre in the ground that have multiple modes and multiple cores.

SDM systems will bring about change not only with the fibre and terminal end points, but also the amplification and optical switching along the transmission path. SDM optical switching will be more complex but it also promises huge capacities and overall dollar-per-bit cost savings.

Tomkos is heading three European research projects - FOX-C, ASTRON & INSPACE.

FOX-C involves adding and dropping all-optically sub-channels from different types of spectral super-channels. ASTRON is undertaing the development of a one terabit transceiver photonic integrated circuit (PIC). The third, INSPACE, will undertake the development of new optical switch architectures for SDM-based networks.

FOX-C

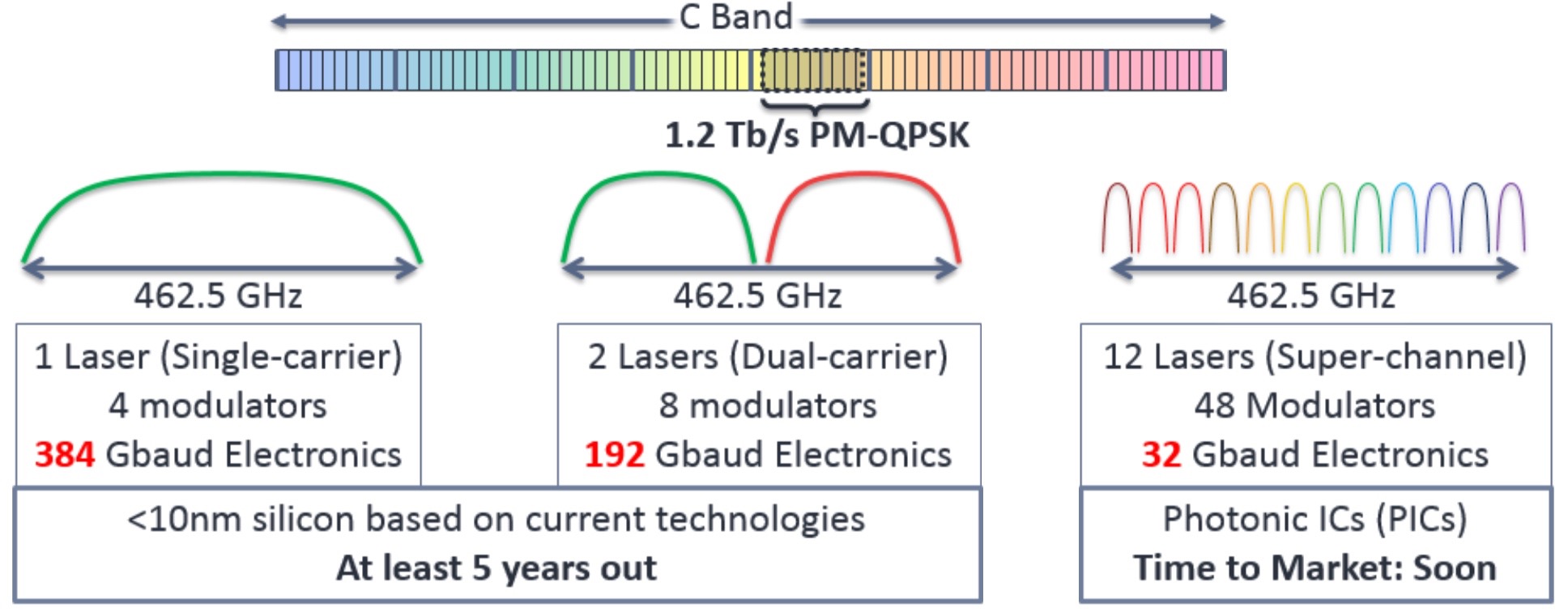

Spectral super-channels are used to create high bit-rate signals - 400 Gigabit and greater - by combining a number of sub-channels. Combining sub-channels is necessary since existing electronics can’t create such high bit rates using a single carrier.

Infinera points out that a 1.2 Terabit-per-second (Tbps) signal implemented using a single carrier would require 462.5 GHz of spectrum while the accompanying electronics to achieve the 384 Gigabaud (Gbaud) symbol rate would require a sub-10nm CMOS process, a technology at least five years away.

- Those that use non-overlapping sub-channels implemented using what is called Nyquist multiplexing.

- And those with overlapping sub-channels using orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM).

OFDM promises compact Terabit transceivers

Source ECI Telecom

Source ECI Telecom

A one Terabit super-channel, crafted using orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (OFDM), has been transmitted over a live network in Germany. The OFDM demonstration is the outcome of a three-year project conducted by the Tera Santa Consortium comprising Israeli companies and universities.

Current 100 Gig coherent networks use a single carrier for the optical transmission whereas OFDM imprints the transmitted data across multiple sub-carriers. OFDM is already used as a radio access technology, the Long Term Evolution (LTE) cellular standard being one example.

With OFDM, the sub-carriers are tightly packed with a spacing chosen to minimise the interference at the receiver. OFDM is being researched for optical transmission as it promises robustness to channel impairments as well as implementation benefits, especially as systems move to Terabit speeds.

"It is clear that the market has voted for single-carrier transmission for 400 Gig," says Shai Stein, chairman of the Tera Santa Consortium and CTO of system vendor, ECI Telecom. "But at higher rates, such as 1 Terabit, the challenge will be to achieve compact, low-power transceivers."

The real contribution [of OFDM] is implementation efficiency

Shai Stein

One finding of the project is that the OFDM optical performance matches that of traditional coherent transmission but that the digital signal processing required is halved. "The real contribution [of OFDM] is implementation efficiency," says Stein.

For the trial, the 175GHz-wide 1 Terabit super-channel signal was transmitted through several reconfigurable optical add/drop multiplexer (ROADM) stages. The 175GHz spectrum comprises seven, 25GHz bands. Two OFDM schemes were trialled: 128 sub-carriers and 1024 sub-carriers across each band.

To achieve 1 Terabit, the net data rate per band was 142 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps). Adding the overhead bits for forward error corrections and pilot signals, the gross data rate per band is closer to 200Gbps.

The 128 or 1024 sub-carriers per band are modulated using either quadrature phase-shift keying (QPSK) or 16-quadrature amplitude modulation (16-QAM). One modulation scheme - QPSK or 16-QAM - was used across a band, although Stein points out that the modulation scheme can be chosen on a sub-carrier by sub-carrier basis, depending on the transmission conditions.

The trial took place at the Technische Universität Dresden, using the Deutsches Forschungsnetz e.V. X-WiN research network. The signal recovery was achieved offline using MATLAB computational software. "It [the trial] was in real conditions, just the processing was performed offline," says Stein. The MATLAB algorithms will be captured in FPGA silicon and added to the transciever in the coming months.

Using a purpose-built simulator, the Tera Santa Consortium compared the OFDM results with traditional coherent super-channel transmission. "Both exhibited the same performance," says David Dahan, senior research engineer for optics at ECI Telecom. "You get a 1,000km reach without a problem." And with hybrid EDFA-Raman amplification, 2,000km is possible. The system also demonstrated robustness to chromatic dispersion. Using 1024 sub-carriers, the chromatic dispersion is sufficient low that no compensation is needed, says ECI.

Stein says the project has been hugely beneficial to the Israeli optical industry: "There has been silicon photonics, transceiver and algorithmic developments, and benefits at the networking level." For ECI, it is important that there is a healthy local optical supply chain. "The giants have that in-house, we do not," says Stein.

One Terabit transmission will be realised in the marketplace in the next two years. Due to the project, the consortium companies are now well placed to understand the requirements, says Stein.

Set up in 2011, the Tera Santa Consortium includes ECI Telecom, Finisar, MultiPhy, Cello, Civcom, Bezeq International, the Technion Israel Institute of Technology, Ben-Gurion University, and the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Bar-Ilan University and Tel-Aviv University.

A FOX-C approach to flexible optical switching

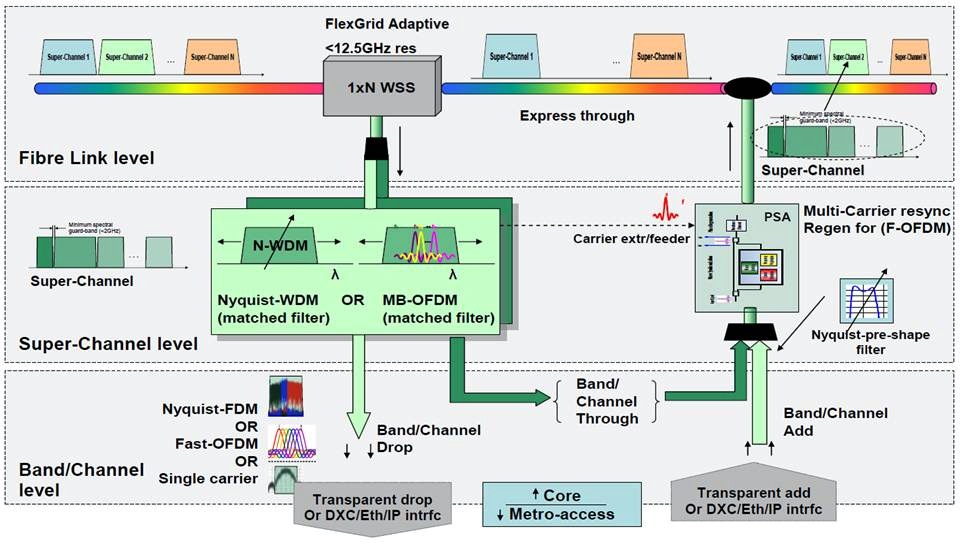

Flexible switching of high-capacity traffic carried over ’super-channel' dense-wavelength division multiplexing wavelengths is the goal of the European Commission Seventh Framework Programme (FP7) research project.

The €3.6M FOX-C (Flexible optical cross-connect nodes) will develop a flexible spectrum reconfigurable optical add/drop multiplexer (ROADM) for 400Gbps and one Terabit optical transmission. The ROADM will be designed not only to switch super-channels but also the carrier constituent components.

Companies involved in the project include operator France Telecom and optical component player Finisar. However, no major European system vendor is taking part in the FOX-C project although W-Onesys, a small system vendor from Spain, is participating.

“We want to transfer to the optical layer the switching capability”

“We want to transfer to the optical layer the switching capability”

Erwan Pincemin, FT-Orange

“It is becoming more difficult to increase the spectral efficiency of such networks,” says Erwan Pincemin, senior expert in fibre optic transmission at France Telecom-Orange. “We want to increase the advantages of the network by adding flexibility in the management of the wavelengths in order to adapt the network as services evolve.”

FOX-C will increase the data rate carried by each wavelength to achieve a moderate increase in spectral efficiency. Pincemin says such modulation schemes as orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM) and Nyquist WDM will be explored. But the main goal is to develop flexible switching based on an energy efficient and cost effective ROADM design.

The ROADM’s filtering will be able to add and drop 10 and 100 Gigabit sub-channels or 400 Gigabit and 1 Terabit super-channels. By using the developed filter to switch optically at speeds as low as 10 Gigabit, the aim is to avoid having to do the switching electrically with its associated cost and power consumption overhead. “We want to transfer to the optical layer the switching capability,” says Pincemin.

While the ROADM design is part of the project’s goals, what is already envisaged is a two-stage pass-through-and-select architecture. The first stage, for coarse switching, will process the super-channels and will be followed by finer filtering to extract (drop) and insert (add) individual lower-rate tributaries.

The project started in Oct 2012 and will span three years. The resulting system testing will take place at France-Telecom Orange's Lab in Lannion, France.

Project players

The project’s technical leader is the Athens Institute of Technology (AIT), headed by Prof. Ioannis Tomkos, while the administrator leader is the Greek company Optronics Technologies.

Finisar will provide the two-stage optical switch while France Telecom-Orange will test the resulting ROADM and will build the multi-band OFDM transmitter and receiver to evaluate the design.

Athens Institute of Technology will work with Finisar on the technical aspects and in particular a flexible networking architecture study. The Hebrew University is working with Finisar on the design and the building of the ultra-selective adaptive optical filter, and has expertise is free-space optical systems. The Spanish firm, W-Onesys, is a system integration specialist and will also work with Finisar to integrate its wavelength-selective switch for the ROADM. Other project players include Aston University, Tyndall National Institute and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.

No major European system vendor is taking part in the FOX-C project. According to Pincemin this is regrettable although he points out that the equipment players are involved in other EC FP7 projects addressing flexible networking.

He believes that their priorities are elsewhere and that the FOX-C project may be deemed as too forward looking and risky. “They want to have a clear return on investment on their research,” says Pincemin.

Briefing: Flexible elastic-bandwidth networks

Vendors and service providers are implementing the first examples of flexible, elastic-bandwidth networks. Infinera and Microsoft detailed one such network at the Layer123 Terabit Optical and Data Networking conference held earlier this year.

Optical networking expert Ioannis Tomkos of the Athens Information Technology Center explains what is flexible, elastic bandwidth.

Part 1: Flexible elastic bandwidth

"We cannot design anymore optical networks assuming that the available fibre capacity is abundant"

Prof. Tomkos

Several developments are driving the evolution of optical networking. One is the incessant demand for bandwidth to cope with the 30+% annual growth in IP traffic. Another is the changing nature of the traffic due to new services such as video, mobile broadband and cloud computing.

"The characteristics of traffic are changing: A higher peak-to-average ratio during the day, more symmetric traffic, and the need to support higher quality-of-service traffic than in the past," says Professor Ioannis Tomkos of the Athens Information Technology Center.

"The growth of internet traffic will require core network interfaces to migrate from the current 10, 40 and 100Gbps to 1 Terabit by 2018-2020"

Operators want a more flexible infrastructure that can adapt to meet these changes, hence their interest in flexible elastic-bandwidth networks. The operators also want to grow bandwidth as required while making best use of the fibre's spectrum. They also require more advanced control plane technology to restore the network elegantly and promptly following a fault, and to simplify the provisioning of bandwidth.

The growth of internet traffic will require core network interfaces to migrate from the current 10, 40 and 100Gbps to 1 Terabit by 2018-2020, says Tomkos. Such bit-rates must be supported with very high spectral efficiencies, which according to latest demonstrations are only a factor of 2 away of the Shannon's limit. Simply put, optical fibre is rapidly approaching its maximum limit.

"We cannot design anymore optical networks assuming that the available fibre capacity is abundant," says Tomkos. "As is the case in wireless networks where the available wireless spectrum/ bandwidth is a scarce resource, the future optical communication systems and networks should become flexible in order to accommodate more efficiently the envisioned shortage of available bandwidth.”

The attraction of multi-carrier schemes and advanced modulation formats is the prospect of operators modifying capacity in a flexible and elastic way based on varying traffic demands, while maintaining cost-effective transport.

Elastic elements

Optical systems providers now realise they can no longer keep increasing a light path's data rate while expecting the signal to still fit in the standard International Telecommunication Union (ITU) - defined 50GHz band.

It may still be possible to fit a 200 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) light path in a 50GHz channel but not a 400Gbps or 1 Terabit signal. At 400Gbps, 80GHz is needed and at 1 Terabit it rises to 170GHz, says Tomkos. This requires networks to move away from the standard ITU grid to a flexible-based one, especially if operators want to achieve the highest possible spectral efficiency.

Vendors can increase the data rate of a carrier signal by using more advanced modulation schemes than dual polarisation, quadrature phase-shift keying (DP-QPSK), the defacto 100Gbps standard. Such schemes include amplitude modulation at 16-QAM, 64-QAM and 256-QAM but the greater the amplitude levels used and hence the data rates, the shorter the resulting reach.

Another technique vendors are using to achieve 400Gbps and 1Tbps data rates is to move from a single carrier to multiple carriers or 'super-channels'. Such an approach boosts the data rate by encoding data on more than one carrier and avoids the loss in reach associated with higher order QAM. But this comes at a cost: using multiple carriers consumes more, precious spectrum.

As a result, vendors are looking at schemes to pack the carriers closely together. One is spectral shaping. Tomkos also details the growing interest in such schemes as optical orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM) and Nyquist WDM. For Nyquist WDM, the subcarriers are spectrally shaped so that they occupy a bandwidth close or equal to the Nyquist limit to avoid inter symbol interference and crosstalk during transmission.

Both approaches have their pros and cons, says Tomkos, but they promise optimum spectral efficiency of 2N bits-per-second-per-Hertz (2N bits/s/Hz), where N is the number of constellation points.

The attraction of these techniques - multi-carrier schemes and advanced modulation formats - is the prospect of operators modifying capacity in a flexible and elastic way based on varying traffic demands, while maintaining cost-effective transport.

"With flexible networks, we are not just talking about the introduction of super-channels, and with it the flexible grid," says Tomkos. "We are also talking about the possibility to change either dynamically."

According to Tomkos, vendors such as Infinera with its 5x100Gbps super-channel photonic integrated circuit (PIC) are making an important first step towards flexible, elastic-bandwidth networks. But for true elastic networks, a flexible grid is needed as is the ability to change the number of carriers on-the-fly.

"Once we have those introduced, in order to get to 1 Terabit, then you can think about playing with such parameters as modulation levels and the number of carriers, to make the bandwidth really elastic, according to the connections' requirements," he says.

Meanwhile, there are still technology advances needed before an elastic-bandwidth network is achieved, such as software-defined transponders and a new advanced control plane.

Tomkos says that operators are now using control plane technology that co-ordinates between layer three and the optical layer to reduce network restoration time from minutes to seconds. Microsoft and Infinera cite that they have gone from tens of minutes down to a few seconds using the more advanced optical infrastructure. "They [Microsoft] are very happy with it," says Tomkos.

But to provision new capacity at the optical layer, operators are talking about requirements in the tens of minutes; something they do not expect will change in the coming years. "Cloud services could speed up this timeframe," says Tomkos.

"There is usually a big lag between what operators and vendors do and what academics do," says Tomkos. "But for the topic of flexible, elastic networking, the lag between academics and the vendors has become very small."

Further reading:

FSAN close to choosing the next generation of PON

Briefing: Next-gen PON

Part 1: NG-PON2

The next-generation passive optical network (PON) will mark a departure from existing PON technologies. Some operators want systems based on the emerging standard for deployment by 2015.

“One of the goals in FSAN is to converge on one solution that can serve all the markets"

Derek Nesset, co-chair of FSAN's NGPON task group

The Full Service Access Network (FSAN) industry group is close to finalising the next optical access technology that will follow on from 10 Gigabit GPON.

FSAN - the pre-standards forum consisting of telecommunications service providers, testing labs and equipment manufacturers - crafted what became the International Telecommunication Union's (ITU) standards for GPON (Gigabit PON) and 10 Gigabit GPON (XGPON1). In the past year FSAN has been working on NG-PON2, the PON technology that comes next.

“One of the goals in FSAN is to converge on one solution that can serve all the markets - residential users, enterprise and mobile backhaul," says Derek Nesset, co-chair of FSAN's NGPON task group.

Some mobile operators are talking about backhaul demands that will require multiple 10 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) links to carry the common public radio interface (CPRI), for example. The key design goal, however, is that NG-PON2 retains the capability to serve residential users cost-effectively, stresses Nesset.

FSAN says it has a good description of each of the candidate technologies: what each system looks like and its associated power consumption. "We are trying to narrow down the solutions and the ideal is to get down to one,” says Nesset.

The power consumption of the proposed access scheme is of key interest for many operators, he says. Another consideration is the risk associated with moving to a novel architecture rather than adopting an approach that builds on existing PON schemes.

Operators such as NTT of Japan and Verizon in the USA have a huge installed base of PON and want to avoid having to amend their infrastructure for any next-generation PON scheme unable to re-use power splitters. Other operators such as former European incumbents are in the early phases of their rollout of PON and have Greenfield sites that could deploy other passive infrastructure technologies such as arrayed waveguide gratings (AWG).

"The ideal is we select a system that operates with both types of infrastructure," says Nesset. "Certain flavours of WDM-PON (wavelength division multiplexing PON) don't need the wavelength splitting device at the splitter node; some form of wavelength-tuning can be installed at the customer premises." That said, the power loss of existing optical splitters is higher than AWGs which impacts PON reach – one of several trade-offs that need to be considered.

Once FSAN has concluded its studies, member companies will generate 'contributions' for the ITU, intended for standardisation. The ITU has started work on defining high-level requirements for NG-PON2 through contributions from FSAN operators. Once the NG-PON2 technology is chosen, more contributions that describe the physical layer, the media access controller and the customer premise equipment's management requirements will follow.

Nesset says the target is to get such documents into the ITU by September 2012 but achieving wide consensus is the priority rather than meeting this deadline. "Once we select something in FSAN, we expect to see the industry ramp up its contributions based on that selected technology to the ITU," says Nesset. FSAN will select the NG-PON2 technology before September.

NG-PON2 technologies

Candidate technologies include an extension to the existing GPON and XGPON1 based on time-division multiplexing (TDM). Already vendors such as Huawei have demonstrated prototype 40 Gigabit capacity PON systems that also support hybrid TDM and WDM-PON (TWDM-PON). Other schemes include WDM-PON, ultra-dense WDM-PON and orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM).

Nesset says there are several OFDM variants being proposed. He views OFDM as 'DSL in the optical domain’: sub-carriers finely spaced in the frequency domain, each carrying low-bit-rate signals.

One advantage of OFDM technology, says Nesset, includes taking a narrowband component to achieve a broadband signal: a narrowband 10Gbps transmitter and receiver can achieve 40Gbps using sub-carriers, each carrying quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM). "All the clever work is done in CMOS - the digital signal processing and the analogue-to-digital conversion," he says. The DSP executes the fast Fourier transform (FFT) and the inverse FFT.

"We are trying to narrow down the solutions and the ideal is to get down to one"

Another technology candidate is WDM-PON including an ultra-dense variant that promises a reach of up to 100km and 1,000 wavelengths. Such a technology uses a coherent receiver to tune to the finely spaced wavelengths.

In addition to being compatible with existing infrastructure, another FSAN consideration is compatibility with existing PON standards. This is to avoid having to do a wholesale upgrade of users. For example, with XGPON1, the optical line terminal (OLT) using an additional pair of wavelengths - a wavelength overlay - sits alongside the existing GPON OLT. ”The same principle is desirable for NG-PON2,” says Nesset.

However, an issue is that spectrum is being gobbled up with each generation of PON. PON systems have been designed to be low cost and the transmit lasers used are not wavelength-locked and drift with ambient temperature. As such they consume spectrum similar to coarse WDM wavelength bands. Some operators such as Verizon and NTT also have a large installed base of analogue video overlay at 1550nm.

”So in the 1500 band you've got 1490nm for GPON, 1550nm for RF (radio frequency) video, and 1577nm for XGPON; there are only a few small gaps,” says Nesset. A technology that can exploit such gaps is both desirable and a challenge. “This is where ultra-dense WDM-PON could come into play,” he says. This technology could fit tens of channels in the small remaining spectrum gaps.

The technological challenges implementing advanced WDM-PON systems that will likely require photonic integration is also a concern for the operators. "The message from the vendors is that ’when you tell us what to do, we have got the technology to do it’,” says Nesset. ”But they need the see the volume applications to justify the investment.” However, operators need to weigh up the technological risks in developing these new technologies and the potential for not realising the expected cost reductions.

Timetable

Nesset points out that each generation of PON has built on previous generations: GPON built on BPON and XGPON on GPON. But NG-PON2 will inevitably be based on new approaches. These include TWDM-PON which is an evolution of XG-PON into the wavelength domain, virtual point-to-point approaches such as WDM-PON that may also use an AWG, and the use of digital signal processing with OFDM or coherent ultra dense WDM-PON. ”It is quite a challenge to weigh up such diverse technological approaches,” says Nesset.

If all goes smoothly it will take two ITU plenary meetings, held every nine months, to finalise the bulk of the NG-PON2 standard. That could mean mid-2013 at the earliest.

FSAN's timetable is based on operators wanting systems deployable in 2015. That requires systems to be ready for testing in 2014.

“[Once deployed] we want NG-PON2 to last quite a while and be scalable and flexible enough to meet future applications and markets as they emerge,” says Nesset.

The evolution of optical networking

An upcoming issue of the Proceeedings of the IEEE will be dedicated solely to the topic of optical networking. This, says the lead editor, Professor Ioannis Tomkos at the Athens Information Technology Center, is a first in the journal's 100-year history. The issue, entitled The Evolution of Optical Networking, will be published in either April or May and will have a dozen invited papers.

One topic that will change the way we think about optical networks is flexible or elastic optical networks.

Professor Ioannis Tomkos

"If I have to pick one topic that will change the way we think about optical networks, it is flexible or elastic optical networks, and the associated technologies," says Tomkos.

A conventional dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) network has fixed wavelengths. For long-haul optical transmission each wavelength has a fixed bit rate - 10, 40 or 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps), a fixed modulation format, and typically occupies a 50GHz channel. "Such a network is very rigid," says Tomkos. "It cannot respond easily to changes in the network's traffic patterns."

This arrangement has come about, says Tomkos, because the assumption has always been that fibre bandwidth is abundant. "But at the moment we are only a factor of two away from reaching the Shannon limit [in terms of spectral efficiency bits/s/Hz) so we are going to hit the fibre capacity wall by 2018-2020," he warns.

The maximum theoretically predicted spectral efficiency for an optical communication system based on standard single-mode fibres is about 9bits/s/Hz per polarisation for typical long-haul system reaches of 500km without regeneration, says Tomkos. "At the moment the most advanced hero experiments demonstrated in labs have achieved a spectral efficiency of about 4-6bits/s/Hz," he says. This equates to a total transmission capacity close to 100 Terabits-per-second (Tbps). After that, deploying more fibre will be the only way to further scale networks.

Accordingly, new thinking is required.

Two approaches are being proposed. One is to treat the optical network in the same way as the air interface in cellular networks: spectrum is scarce and must be used effectively.

"We are running close to fundamental limits, that's why the optical spectrum of available deployed standard single mode fibers should be utilized more efficiently from now on as is the case with wireless spectrum," says Tomkos.

How optical communication is following in the footsteps of wireless.

The second technique - spatial multiplexing - looks to extend fibre capacity well beyond what can be achieved using the first approach alone. Such an option would need to deploy new fibre types that support multiple cores or multi-mode transmission.

Flexible spectrum

"We have to start thinking about techniques used in wireless networks to be adopted in optical networks," says Tomkos (See text box). With a flexible network, the thinking is to move from the 50GHz fixed grid, down to 12.50GHz, then 6.25GHz or 1.50GHz or even eliminate the ITU grid entirely, he says. Such an approach is dubbed flexible spectrum or a gridless network.

With such an approach, the optical transponders can tune the bit rate and the modulation format according to the reach and capacity requirements. The ROADMs or, more aptly, the wavelength-selective switches (WSSes) on which they are based, also have to support such gridless operation.

WSS vendors Finisar and Nistica already support such a flexible spectrum approach, while JDS Uniphase has just announced it is readying its first products. Meanwhile US operator Verizon is cheerleading the industry to support gridless. "I'm sure Verizon is going to make this happen, as it did at 100 Gigabit," says Tomkos.

Spatial multiplexing

The simplest way to implement spatial multiplexing is to use several fibres in parallel. However, this is not cost-effective. Instead, what is being proposed is to create multi-core fibres - fibres that have more than one core - seven, 19 or more cores in an hexagonal arrangement, down which light can be transmitted. "That will increase the fibre's capacity by a factor of ten of 20," says Tomkos.

Another consideration is to move from single-mode to multi-mode fibre that will support the transmission of multiple modes, as many as several hundred.

The issue with multi-mode fibre is its very high modal dispersion which limits its bandwidth-distance product. "Now with improved techniques from signal processing like MIMO [multiple-input, multiple out] processing, OFDM [orthogonal frequency division multiplexing] to more advanced optical technologies, you can think that all these multiple modes in the fibre can be used potentially as independent channels," says Tomkos. "Therefore you can potentially multiply your fibre capacity by 100x or 200x."

The Proceedings of the IEEE issue will have a paper on flexible networking by NEC Labs, USA, and a second, on the ultimate capacity limits in optical communications, authored by Bell Labs.

Further reading:

MODE-GAP EU Seventh Framework project, click here.

OFC/NFOEC 2012: Technical paper highlights

Source: The Optical Society

Source: The Optical Society

Novel technologies, operators' experiences with state-of-the-art optical deployments and technical papers on topics such as next-generation PON and 400 Gigabit and 1 Terabit optical transmission are some of the highlights of the upcoming OFC/NFOEC conference and exhibition, to be held in Los Angeles from March 4-8, 2012. Here is a taste of some of the technical paper highlights.

Optical networking

In Spectrum, Cost and Energy Efficiency in Fixed-Grid and Flew-Grid Networks (Paper number 1248601) an evaluation of single and multi-carrier networks at rates up to 400 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) is made by the Athens Information Technology Center. One finding is that efficient spectrum utilisation and fine bit-rate granularity are essential if cost and energy efficiencies are to be realised.

In several invited papers, operators report their experiences with the latest networking technologies. AT&T Labs discusses advanced ROADM networks; NTT details the digital signal processing (DSP) aspects of 100Gbps DWDM systems and, in a separate paper, the challenge for Optical Transport Network (OTN) at 400Gbps and beyond, while Verizon gives an update on the status of MPLS-TP. As part of the invited papers, Finisar's Chris Cole outlines the next-generation CFP modules.

Optical access

Fabrice Bourgart of FT-Orange Labs details where the next generation PON standards - NGPON2 - are going while NeoPhotonics's David Piehler outlines the state of photonic integrated circuit (PIC) technologies for PONS. This is also a topic tackled by Oclaro's Michael Wale: PICs for next-generation optical access systems. Meanwhile Ao Zhang of Fiberhome Telecommunication Technologies discusses the state of FTTH deployments in the world's biggest market, China.

Switching, filtering and interconnect optical devices

NTT has a paper that details a flexible format modulator using a hybrid design based on a planar lightwave circuit (PLC) and lithium niobate. In a separate paper, NTT discusses silica-based PLC transponder aggregators for a colourless, directionless and contentionless ROADM, while Nistica's Tom Strasser discusses gridless ROADMs. Compact thin-film polymer modulators for telecoms is a subject tackled by GigOptix's Raluca Dinu.

One novel paper is on graphene-based optical modulators by Ming Liu, Xiang at the UC Berkeley (Paper Number: 1249064). The optical loss of graphene can be tuned by shifting its Fermi level, he says. The paper shows that such tuning can be used for a high-speed optical modulator at telecom wavelengths.

Optoelectronic Devices

CMOS photonic integrated circuits is the topic discussed by MIT's Rajeev Ram, who outlines a system-on-chip with photonic input and output. Applications range from multiprocessor interconnects to coherent communications (Paper Number: 1249068).

A polarisation-diversity coherent receiver on polymer PLC for QPSK and QAM signals is presented by Thomas Richter of the Fraunhofer Institute for Telecommunications (Paper Number: 1249427). The device has been tested in systems using 16-QAM and QPSK modulation up to 112 Gbps.

Core network

Ciena's Maurice O'Sullivan outlines 400Gbps/ 1Tbps high-spectral efficiency technology and some of the enabling subsystems. Alcatel-Lucent's Steven Korotky discusses traffic trends: drivers and measures of cost-effective and energy-efficient technologies and architectures for the optical backbone networks, while transport requirements for next-generation heterogeneous networks is the subject tackled by Bruce Nelson of Juniper Networks.

Data centre

IBM's Casimir DeCusatis presents a future - 2015-and-beyond - view of data centre optical networking. The data centre is also tackled by HP's Moray McLaren, in his paper on future computing architectures enabled by optical and nanophotonic interconnects. Optically-interconnected data centres are also discussed by Lei Xu of NEC Labs America.

Expanding usable capacity of fibre syposium

There is a special symposium at OFC/ NFOEC entitled Enabling Technologies for Fiber Capacities Beyond 100 Terabits/second. The papers in the symposium discuss MIMO and OFDM, technologies more commonly encountered in the wireless world.

R&D: At home or abroad?

Omer Industrial Park in the Negev, Israel - the location of ECI Telecom's latest R&D centre.

Omer Industrial Park in the Negev, Israel - the location of ECI Telecom's latest R&D centre.

Chaim Urbach likes working at the Omer Industrial Park site. Normally located at ECI’s headquarters in Petah Tikva, he visits the Omer site - some 100km away - once or twice a week and finds he is more productive there. Urbach employs an open door policy and has fewer interruptions at the Omer site since engineers are focussed solely on R&D work.

ECI set up its latest R&D centre in May 2010 with a staff of ten. “In 2009 we realised we needed more engineers,” says Urbach. One year on the site employs 150, by the end of the year it will be 200, and by year-end 2012 the company expects to employ 300. ECI has already taken one unit at the Industrial Park and its operations have already spilt over into a second building.

Urbach says that the decision to locate the new site in the south of Israel was not straightforward.

The company has 1,300 R&D staff, with research centres in the US, India and China. Having a second site in Israel helps in terms of issues of language and time zones but employing an R&D engineer in Israel is several times more costly than an engineer in India or China.

The photos on the wall are part of the winning entries in an ECI company-wide photo competition.

The photos on the wall are part of the winning entries in an ECI company-wide photo competition.

But the Israeli Government’s Office of the Chief Scientist (OCS) is keen to encourage local high-tech ventures and has helped with the funding of the site. In return the backed-venture must undertake what is deemed innovative research with the OCS guaranteed royalties from sales of future telecom systems developed at the site.

One difficulty Urbach highlights is recruiting experienced hardware and software engineers given that there are few local high-tech companies in the south of the country. Instead ECI has relocated experienced engineering managers from Petah Tikva, tasked with building core knowledge by training graduates from nearby Ben-Gurion University and from local colleges.

Work on the majority of ECI’s new projects in being done at the Omer site, says Urbach. Projects include developing GPON access technology for a BT tender as well as extending its successful XDM hybrid+ SDH to all-IP transport platform, which has over 30% market share in India. ECI is undertaking the research on one terabit transmission using OFDM technology, part of the Tera Santa Consortium, at its HQ.

“We realised we needed more engineers”

“We realised we needed more engineers”

Chaim Urbach, ECI Telecom

Urbach admits it is a challenge to compete with leading Far Eastern system vendors on cost and given their R&D budgets. But he says the company is focussed on building innovative platforms delivered as part of a complete solution. “We do not just provide a box,” says Urbach. “And customers know if they have a problem, we go the extra mile to solve it.”

Omer Industrial Park

The company is highly business oriented, he says, delivering solutions that fit customers’ needs. “Over 95% of all systems ECI has developed have been sold,” he says.

Urbach also argues that Israeli engineers are suited to R&D. “Engineers don’t do everything by the book,” he says. “And they are dedicated and motivated to succeed.”

For more photos of the Omer Industrial Park, click here

Terabit Consortium embraces OFDM

“This project is very challenging and very important”

“This project is very challenging and very important”

Shai Stein, Tera Santa Consortium

Given the continual growth in IP traffic, higher-speed light paths are going to be needed, says Shai Stein, chairman of the Tera Santa Consortium and ECI Telecom’s CTO: “If 100 Gigabit is starting to be deployed, within five years we’ll start to see links with tenfold that capacity, meaning one Terabit.”

The project is funded by the seven participating firms and the Israeli Government. According to Stern, the Government has invested little in optical projects in recent years. “When we look at the [Israeli] academies and industry capabilities in optical, there is no justification for this,” says Stern. “We went with this initiative in order to get Government funding for something very challenging that will position us in a totally different place worldwide.”

Orthogonal frequency division multiplexing

OFDM differs from traditional dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) technology in how fibre bandwidth is used. Rather than sending all the information on a lightpath within a single 50 or 100GHz channel – dubbed single-carrier transmission – OFDM uses multiple narrow carriers. “Instead of using the whole bandwidth in one bulk and transmitting the information over it, [with OFDM] you divide the spectrum into pieces and on each you transmit a portion of the data,” says Stein. “Each sub-carrier is very narrow and the summation of all of them is the transmission.”

“Each time there is a new arena in telecom we find that there is a battle between single carrier modulation and OFDM; VDSL began as single carrier and later moved to OFDM,” says Amitai Melamed, involved in the project and a member of ECI’s CTO office. “In the optical domain, before running to [use] single-carrier modulation as is currently done at 100 Gigabit, it is better to look at the OFDM domain in detail rather than jump at single-carrier modulation and question whether this was the right choice in future.”

OFDM delivers several benefits, says Stern, especially in the flexibility it brings in managing spectrum. OFDM allows a fibre’s spectrum band to be used right up to its edge. Indeed Melamed is confident that by adopting OFDM for optical, the spectrum efficiency achieved will eventually match that of wireless.

“OFDM is very tolerant to rate adaptation.”

Amitai Melamed, ECI Telecom

The technology also lends itself to parallel processing. “Each of the sub-carriers is orthogonal and in a way independent,” says Stern. “You can use multiple small machines to process the whole traffic instead of a single engine that processes it all.” With OFDM, chromatic dispersion is also reduced because each sub-carrier is narrow in the frequency domain.

Using OFDM, the modulation scheme used per sub-carrier can vary depending on channel conditions. This delivers a flexibility absent from existing single-carrier modulation schemes such as quadrature phase-shift keying (QPSK) that is used across all the channel bandwidth at 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps). “With OFDM, some of the bins [sub-carriers] could be QPSK but others could be 16-QAM or even more,” says Melamed.

The approach enables the concept of an adaptive transponder. “I don’t always need to handle fibre as a time-division multiplexed link – either you have all the capacity or nothing,” says Melamed. “We are trying to push this resource to be more tolerant to the media: We can sense the channels' and adapt the receiver to the real capacity.” Such an approach better suits the characteristics of packet traffic in general he says: “OFDM is very tolerant to rate adaptation.”

The Consortium’s goal is to deliver a 1 Terabit light path in a 175GHz channel. At present 160, 40Gbps can be crammed within the a fibre's C-band, equating to 6.4Tbps using 25GHz channels. At 100Gbps, 80 channels - or 8Tbps - is possible using 50GHz channels. A 175GHz channel spacing at 1Tbps would result in 23Tbps overall capacity. However this figure is likely to be reduced in practice since frequency guard-bands between channels are needed. The spectrum spacings at speeds greater than 100Gbps are still being worked out as part of ITU work on "gridless" channels (see OFC announcements and market trends story).

ECI stresses that fibre capacity is only one aspect of performance, however, and that at 1Tbps the optical reach achieved is reduced compared to transmissions at 100Gbps. “It is not just about having more Gigabit-per-second-per-Hertz but how we utilize the resource,” says Melamed. “A system with an adaptive rate optimises the resource in terms of how capacity is managed.” For example if there is no need for a 1Tbps link at a certain time of the day, the system can revert to a lower speed and use the spectrum freed up for other services. Such a concept will enable the DWDM system to be adaptive in capacity, time and reach.

Project focus

The project is split between digital and analogue, optical development work. The digital part concerns OFDM and how the signals are processed in a modular way.

The analogue work involves overcoming several challenges, says Stern. One is designing and building the optical functions needed for modulation and demodulation with the accuracy required for OFDM. Another is achieving a compact design that fits within an optical transceiver. Dividing the 1Tbps signal into several sub-bands will require optical components to be implemented as a photonic integrated circuit (PIC). The PIC will integrate arrays of components for sub-band processing and will be needed to achieve the required cost, space and power consumption targets.

Taking part in the project are seven Israeli companies - ECI Telecom, the Israeli subsidiary of Finisar, MultiPhy, Civcom, Orckit-Corrigent, Elisra-Elbit and Optiway- as well as five Israeli universities.

Two of the companies in the Consortium

“There are three types of companies,” says Stern. “Companies at the component level – digital components like digital signal processors and analogue optical components, sub-systems such as transceivers, and system companies that have platforms and a network view of the whole concept.”

The project goal is to provide the technology enablers to build a terabit-enabled optical network. A simple prototype will be built to check the concepts and the algorithms before proceeding to the full 1Terabit proof-of-concept, says Stern. The five Israeli universities will provide a dozen research groups covering issues such as PIC design and digital signal processing algorithms.

Any intellectual property resulting from the project is owned by the company that generates it although it will be made available to any other interested Consortium partner for licensing.

Project definition work, architectures and simulation work have already started. The project will take between 3-5 years but it has a deadline after three years when the Consortium will need to demonstrate the project's achievements. “If the achievements justify continuation I believe we will get it [a funding extension],” says Stern. “But we have a lot to do to get to this milestone after three years.

Project funding for the three years is around US $25M, with the Israeli Office of the Chief Scientist (OCS) providing 50 million NIS (US $14.5M) via the Magnet programme, which ECI says is “over half” of the overall funding.

Further reading:

Optical transmission beyond 100Gbps

Part 3: What's next?

Given the 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) optical transmission market is only expected to take off from 2013, addressing what comes next seems premature. Yet operators and system vendors have been discussing just this issue for at least six months.

And while it is far too early to talk of industry consensus, all agree that optical transmission is becoming increasingly complex. As Karen Liu, vice president, components and video technologies at market research firm Ovum, observed at OFC 2010, bandwidth on the fibre is no longer plentiful.

“We need to keep a very close eye that we are not creating more problems than we are solving.”

“We need to keep a very close eye that we are not creating more problems than we are solving.”

Brandon Collings, JDS Uniphase.

As to how best to extend a fibre’s capacity beyond 80, 100Gbps dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) channels spaced 50GHz apart, all options are open.

“What comes after 100Gbps is an extremely complicated question,” says Brandon Collings, CTO of JDS Uniphase’s consumer and commercial optical products division. “It smells like it will entail every aspect of network engineering.”

Ciena believes that if operators are to exploit future high-speed transmission schemes, new architected links will be needed. The rigid networking constraints imposed on 40 and 100Gbps to operate over existing 10Gbps networks will need to be scrapped.

“It will involve a much broader consideration in the way you build optical systems,” says Joe Berthold, Ciena’s vice president of network architecture. “For the next step it is not possible [to use existing 10Gbps links]; no-one can magically make it happen.”

Lightpaths faster than 100Gbps simply cannot match the performance of current optical systems when passing through multiple reconfigurable optical add/drop multiplexer (ROADM) stages using existing amplifier chains and 50GHz channels.

Increasing traffic capacity thus implies re-architecting DWDM links. “Whatever the solution is it will have to be cheap,” says Berthold. This explains why the Optical Internetworking Forum (OIF) has already started a work group comprising operators and vendors to align objectives for line rates above 100Gbps.

If new links are put in then changing the amplifier types and even their spacing becomes possible, as is the use of newer fibre. “If you stay with conventional EDFAs and dispersion managed links, you will not reach ultimate performance,” says Jörg-Peter Elbers, vice president, advanced technology at ADVA Optical Networking,

Capacity-boosting techniques

Achieve higher speeds while matching the reach of current links will require a mixture of techniques. Besides redesigning the links, modulation schemes can be extended and new approaches used such as going ‘gridless” and exploiting sophisticated forward error-correction (FEC) schemes.

For 100Gbps, polarisation and phase modulation in the form of dual polarization, quadrature phase-shift keying (DP-QPSK) is used. By adding amplitude modulation, quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM) schemes can be extended to include 16-QAM, 64-QAM and even 256 QAM.

Alcatel-Lucent is one firm already exploring QAM schemes but describes improving spectral efficiency using such schemes as a law of diminishing returns. For example, 448Gbps based on 64-QAM achieves a bandwidth of 37GHz and a sampling rate of 74 Gsamples/s but requires use of high-resolution A/D converters. “This is very, very challenging,” says Sam Bucci, vice president, optical portfolio management at Alcatel-Lucent.

Infinera is also eyeing QAM to extend the data performance of its 10-channel photonic integrated circuits (PICs). Its roadmap goes from today’s 100Gbps to 4Tbps per PIC.

Infinera has already announced a 10x40Gbps PIC and says it can squeeze 160 such channels in the C-band using 25GHz channel spacing. To achieve 1 Terabit would require a 10x100Gbps PIC.

How would it get to 2Tbps and 4Tbps? “Using advanced modulation technology; climbing up the QAM ladder,” says Drew Perkins, Infinera’s CTO.

Glenn Wellbrock, director of backbone network design at Verizon Business, says it is already very active in exploring rates beyond 100Gbps as any future rate will have a huge impact on the infrastructure. “No one expects ultra-long-haul at greater than 100Gbps using 16-QAM,” says Wellbrock.

Another modulation approach being considered is orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (OFDM). “At 100Gbps, OFDM and the single-carrier approach [DP-QPSK] have the same spectral efficiency,” says Jonathan Lacey, CEO of Ofidium. “But with OFDM, it’s easy to take the next step in spectral efficiency – required for higher data rates - and it has higher tolerance to filtering and polarisation-dependent loss.”

One idea under consideration is going “gridless”, eliminating the standard ITU wavelength grid altogether or using different sized bands, each made up of increments of narrow 25GHz ones. “This is just in the discussion phase so both options are possible,” says Berthold, who estimates that a gridless approach promises up to 30 percent extra bandwidth.

Berthold favours using channel ‘quanta’ rather than adopting a fully flexibility band scheme - using a 37GHz window followed by a 17GHz window, for example - as the latter approach will likely reduce technology choice and lead to higher costs.

Wellbrock says coarse filtering would be needed using a gridless approach as capturing the complete C-Band would be too noisy. A band 5 or 6 channels wide would be grabbed and the signal of interest recovered by tuning to the desired spectrum using a coherent receiver’s tunable laser, similar to how a radio receiver works.

Wellbrock says considerable technical progress is needed for the scheme to achieve a reach of 1500km or greater.

“Whatever the solution is it will have to be cheap”

“Whatever the solution is it will have to be cheap”

Joe Berthold, Ciena.

JDS Uniphase’s Collings sounds a cautionary note about going gridless. “50GHz is nailed down – the number of questions asked that need to be addressed once you go gridless balloons,” he says. “This is very complex; we need to keep a very close eye that we are not creating more problems than we are solving.”

“Operators such as AT&T and Verizon have invested heavily in 50GHz ROADMs, they are not just going to ditch them,” adds Chris Clarke, vice president strategy and chief engineer at Oclaro.

More powerful FEC schemes and in particular soft-decision FEC (SD-FEC) will also benefit optical performance for data rates above 100Gbps. SD-FEC delivers up to a 1.3dB coding gain improvement compared to traditional FEC schemes at 100Gbps.

SD-FEC also paves the way for performing joint iterative FEC decoding and signal equalisation at the coherent receiver, promising further performance improvements, albeit at the expense of a more complex digital signal processor design.

400Gbps or 1 Tbps?

Even the question of what the next data rate after 100Gbps will be –200Gbps, 400Gbps or even 1 Terabit-per -second – remains unresolved.

Verizon Business will deploy new 100Gbps coherent-optimised routes from 2011 and would like as much clarity as possible so that such routes are future-proofed. But Collings points out that this is not something that will stop a carrier addressing immediate requirements. “Do they make hard choices that will give something up today?” he says.

At the OFC Executive Forum, Verizon Business expressed a preference for 1Tbps lightpaths. While 400Gbps was a safe bet, going to 1Tbps would enable skipping one additional stage i.e. 400Gbps. But Verizon recognises that backing 1Tbps depends on when such technology would be available and at what cost.

According to BT, speeds such as 200, 400Gbps and even 1 Tbps are all being considered. “The 200/ 400Gbps systems may happen using multiple QAM modulation,” says Russell Davey, core transport Layer 1 design manager at BT. “Some work is already being done at 1Tbps per wavelength although an alternative might be groups or bands of wavelengths carrying a continuous 1Tbps channel, such as ten 100Gbps wavelengths or five 200Gbps wavelengths.”

Davey stresses that the industry shouldn’t assume that bit rates will continue to climb. Multiple wavelengths at lower bitrates or even multiple fibres for short distances will continue to have a role. “We see it as a mixed economy – the different technologies likely to have a role in different parts of network,” says Davey.

Niall Robinson, vice president of product marketing at Mintera, is confident that 400Gbps will be the chosen rate.

Traditionally Ethernet has grown at 10x rates while SONET/SDH has grown in four-fold increments. However now that Ethernet is a line side technology there is no reason to expect the continued faster growth rate, he says. “Every five years the line rate has increased four-fold; it has been that way for a long time,” says Robinson. “100Gbps will start in 2012/ 2013 and 400Gbps in 2017.”

“There is a lot of momentum for 400Gbps but we’ll have a better idea in a six months’ time,” says Matt Traverso, senior manager, technical marketing at Opnext. “The IEEE [and its choice for the next Gigabit Ethernet speed after 100GbE] will be the final arbiter.”

Software defined optics and cognitive optics

Optical transmission could ultimately borrow two concepts already being embraced by the wireless world: software defined radio (SDR) and cognitive radio.

SDR refers to how a system can be reconfigured in software to implement the most suitable radio protocol. In optical it would mean making the transmitter and receiver software-programmable so that various transmission schemes, data rates and wavelength ranges could be used. “You would set up the optical transmitter and receiver to make best use of the available bandwidth,” says ADVA Optical Networking’s Elbers.

This is an idea also highlighted by Nokia Siemens Networks, trading capacity with reach based on modifying the amount of information placed on a carrier.

“For a certain frequency you can put either one bit [of information] or several,” says Oliver Jahreis, head of product line management, DWDM at Nokia Siemens Networks. “If you want more capacity you put more information on a frequency but at a lower signal-to-noise ratio and you can’t go as far.”

Using ‘cognitive optics’, the approach would be chosen by the optical system itself using the best transmission scheme dependent capacity, distance and performance constraints as well as the other lightpaths on the fibre. “You would get rid of fixed wavelengths and bit rates altogether,” says Elbers.

Market realities

Ovum’s view is it remains too early to call the next rate following 100Gbps.

Other analysts agree. “Gridless is interesting stuff but from a commercial standpoint it is not relevant at this time,” says Andrew Schmitt, directing analyst, optical at Infonetics Research.

Given that market research firms look five years ahead and the next speed hike is only expected from 2017, such a stance is understandable.

Optical module makers highlight the huge amount of work still to be done. There is also a concern that the benefits of corralling the industry around coherent DP-QPSK at 100Gbps to avoid the mistakes made at 40Gbps will be undone with any future data rate due to the choice of options available.

Even if the industry were to align on a common option, developing the technology at the right price point will be highly challenging.

“Many people in the early days of 100Gbps – in 2007 – said: ‘We need 100Gbps now – if I had it I’d buy it’,” says Rafik Ward, vice president of marketing at Finisar. “There should be a lot of pent up demand [now].” The reason why there isn’t is that such end users always miss out key wording at the end, says Ward: “If I had it I’d buy it - at the right price.”

For Part 1, click here

For Part 2, click here