Infinera goes multi-terabit with its latest photonic IC

In his new book, The Great Acceleration, Robert Colvile discusses how things we do are speeding up.

In 1845 it took U.S. President James Polk six months to send a message to California. Just 15 years later Abraham Lincoln's inaugural address could travel the same distance in under eight days, using the Pony Express. But the use of ponies for transcontinental communications was shortlived once the electrical telegraph took hold. [1]

The relentless progress in information transfer, enabled by chip advances and Moore's law, is taken largely for granted. Less noticed is the progress being made in integrated photonic chips, most notably by Infinera.

In 2000, optical transport sent data over long-haul links at 10 gigabit-per-second (Gbps), with 80 such channels supported in a platform. Fifteen years later, Infinera demonstrated its latest-generation photonic integrated circuit (PIC) and FlexCoherent DSP-ASIC that can transmit data at 600Gbps over 12,000km, and up to 2.4 terabit-per-second (Tbps) - three times the data capacity of a state-of-the-art dense wavelength-division multiplexing (DWDM) platform back in 2000 - over 1,150km.

Infinite Capacity Engine

Infinera dubs its latest optoelectronic subsystem the Infinite Capacity Engine. The subsystem comprises a pair of indium-phosphide PICs - a transmitter and a receiver - and the FlexCoherent DSP-ASIC. The performance capabilities that the Infinite Capacity Engine enables were unveiled by Infinera in January with its Advanced Coherent Toolkit announcement. Now, to coincide with OFC 2016, Infinera has detailed the underlying chips that enable the toolkit. And company product announcements using the new hardware will be made later this year, says Pravin Mahajan, the company's director of product and corporate marketing.

The claimed advantages of the Infinite Capacity Engine include a 82 percent reduction in power consumption compared to a system using discrete optical components and a dozen 100-gigabit coherent DSP-ASICs, and a 53 percent reduction in total-cost-of-ownership compared to competing dense WDM platforms. The FlexCoherent chip also features line rate data encryption.

"The Infinite Capacity Engine is the industry's first multi-terabit it super-channel, says Mahajan. "It also delivers the industry's first multi-terabit layer one encryption."

Multi-terabit PIC

Infinera's first transmitter and receiver PIC pair, launched in 2005, supported 10, 10-gigabit channels and implemented non-coherent optical transmission.

In 2011 Infinera introduced a 500-gigabit super-channel coherent PIC pair used with Infinera's DTN-X platforms and also its Cloud Xpress data centre interconnect platform launched in 2014. The 500 Gigabit design implemented 10, 50 gigabit channels that implemented polarisation-multiplexed, quadrature phase-shift keying (PM-QPSK) modulation. The accompanying FlexCoherent DSP-ASIC was implemented using a 40nm CMOS process node and support a symbol rate of 16 gigabaud.

The PIC design has since been enhanced to also support additional modulation schemes such as as polarisation-multiplexed, binary phase-shift keying (PM-BPSK) and 3 quadrature amplitude modulation (PM-3QAM) that extend the DTN-X's ultra long-haul performance.

In 2015 Infinera also launched the oPIC-100, a 100-gigabit PIC for metro applications that enables Infinera to exploit the concept of sliceable bandwidth by pairing oPIC-100s with a 500 gigabit PIC. Here the full 500 gigabit super-channel capacity can be pre-deployed even if not all of the capacity is used. Using Infinera's time-based instant bandwidth feature, part of that 500 gigabit capacity can be added between nodes in a few hours based on a request for greater bandwidth.

Now, with the Infinite Capacity Engine PIC, the effective number of channels has been expanded to 12, each capable of supporting a range of modulation techniques (see table below) and data rates. In fact, Infinera uses multiple Nyquist sub-carriers spread across each of the 12 channels. By encoding the data across multiple sub-carriers a lower-baud rate can be used, increasing the tolerance to non-linear channel impairments during optical transmission.

Mahajan says the latest PIC has a power consumption similar to its current 500 Gigabit super-channel PIC but because the photonic design supports up to 2.4 terabit, the power consumption in gigabit-per-Watt is reduced by 70 percent.

FlexCoherent encryption

The latest FlexCoherent DSP-ASIC is Infinera's most complex yet. The 1.6 billion transistor 28nm CMOS IC can process two channels, and supports a 33 gigabaud symbol rate. As a result, six DSP-ASICs are used with the 12-channel PIC.

It is the DSP-ASIC that enables the various elements of the advanced coherent toolkit that includes improved soft-decision forward error correction. "The net coding gain is 11.9dB, up 0.9 dB, which improves the capacity-reach," says Mahajan. Infinera says the ultra long-haul performance has also been improved from 9,500km to over 12,000km.

Source: Infinera

Source: Infinera

The DSP also features layer one encryption implementing the 256-bit Advanced Encryption Standard (AES-256). Infinera says the request for encryption is being led by the Internet content providers but wholesale operators and co-location providers also want to secure transmissions between sites.

Infinera introduced layer two MACsec encryption with its Cloud Xpress platform. This encrypts the Ethernet payload but not the header. With layer one encryption, it is the OTN frames that are encoded. "When we get down to the OTN level, everything is encrypted," says Mahajan. An operator can choose to encrypt the entire super-channel or encrypt at the service level, down to the ODU0 (1.244 Gbps) level.

System benefits

Using the Infinite Capacity Engine, the transmission capacity over a fibre increases from 9.5 terabit to up to 26.4 terabit.

And with the newest PIC, Infinera can expand the sliceable transponder concept for metro-regional applications. The 2.4 terabits of capacity can be pre-deployed and new capacity turned up between nodes. "You can suddenly turn up 200 gigabit for a month or two, rent and then return it," says Mahajan. However, to support the full 2.4 terabits of capacity, the PIC at the other end of the link would also need to support 16-QAM.

Infinera does say there will be other Infinite Capacity Engine variants. "There will be specific engines for specific markets, and we would choose a subset of the modulations," says Mahajan.

One obvious platform that will benefit from the first Infinite Capacity Engine is the DTN-X. Another that will likely use an ICE variant is Infinera's Cloud Xpress. At present Infinera integrates its 500-gigabit PIC in a 2 rack-unit box for data centre interconnect applications. By using the new PIC and implementing PM-16QAM, the line-side capacity per rack unit of a second-generation Cloud Xpress would rise from 250 gigabit to 1.2 terabit. And with layer one encryption, the MACsec IC may no longer be needed.

Mahajan says the Infinite Capacity Engine has already been tested in the Telstra trial detailed in January. "We have already proven its viability but it is not deployed and carrying live traffic," he says.

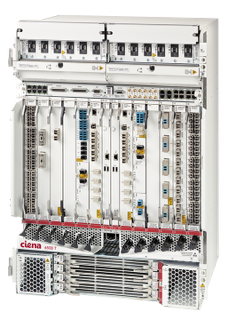

Ciena enhances its 6500 packet-optical transport family

"The 6500 T-Series is a big deal as Ciena can offer two different systems depending on what the customer is looking for," says Andrew Schmitt, founder and principal analyst of market research firm, Cignal AI.

Helen XenosIf customers want straightforward transport and the ability to reach a number of different distances, there is the existing 6500 S-series, says Schmitt. The T-series is a system specifically for metro-regional networks that can accommodate multiple traffic types – OTN or packet.

Helen XenosIf customers want straightforward transport and the ability to reach a number of different distances, there is the existing 6500 S-series, says Schmitt. The T-series is a system specifically for metro-regional networks that can accommodate multiple traffic types – OTN or packet.

"It has very high density for a packet-optical system and offers pay-as-you-grow with CFP2-ACO [coherent pluggable] modules," says Schmitt.

Ciena says the T-series has been developed to address new connectivity requirements service providers face. Content is being shifted to the metro to improve the quality of experience for end users and reduce capacity on backbone networks. Such user consumption of content is one factor accounting for the strong annual 40 percent growth in metro traffic.

According to Ciena, service providers have to deploy multiple overlays of network elements to scale capacity, including at the photonic switch layer, because they need more than 8-degree reconfigurable optical add/ drop multiplexers (ROADMs).

Operators are looking for a next-generation platform for these very high-capacity switching locations to efficiently distribute content

But overlays add complexity to the metro network and slow the turn-up times of services, says Helen Xenos, director, product and technology marketing at Ciena: "Operators are looking for a next-generation platform for these very high-capacity switching locations to efficiently distribute content."

U.S. service provider Verizon is the first to announce the adoption of the 6500 T-series to modernise its metro and is now deploying the platform. "Verizon is dealing with a heterogeneous network in the metro with many competing requirements," says Schmitt. "They don’t have the luxury of starting over or specialising like some of the hyper-scale transport architectures."

The T-series, once deployed, will handle the evolving requirements of Verizon's network. "Sure, it comes with additional costs compared with bare-bones transport but my conversation with folks at Verizon would indicate flexibility is worth the price," says Schmitt.

Ciena has over 500 customers in 50 countries for its existing 6500 S-series. Customers include 18 of the top 25 communications service providers and three of the top five content providers.

Xenos says an increasing number of service providers are interested in its latest platform. The T-series is part of six request-for-proposals (RFPs) and is being evaluated in several service providers' labs. The 6500 T-series will be generally available this month.

6500 T-series

The existing 6500 S-series family comprises four platforms, from the 2 rack-unit (RU) 6500-D2 chassis to the 22RU 6500-S32 that supports Ethernet, time-division multiplexed traffic and wavelength division multiplexing, and 3.2 terabit-per-second (Tbps) packet/ Optical Transport Network (OTN) switching.

The two T-series platforms are the half rack 6500-12T and the full rack 6500-24T. The cards have been upgraded from 100-gigabit switching per slot to 500-gigabit per slot.

The 6500-T12 has 12 service slots which house either service interfaces or photonic modules. There are also 2 control modules. Shown at the base of the chassis are four 500 Gig switching modules. Source: Ciena

The 6500-T12 has 12 service slots which house either service interfaces or photonic modules. There are also 2 control modules. Shown at the base of the chassis are four 500 Gig switching modules. Source: Ciena

The 500 gigabit switching per slot means the 6500-12T supports 6 terabits of switching capacity while the -24T will support 12 terabits by year end. The platforms have been tested and will support 1 terabit per slot, such that the -24T will deliver the full 24 terabit. Over 100 terabit of switching capacity will be possible in a multiple-chassis configuration, managed as a single switching node.

The latest platforms can use Ciena's existing coherent line cards that support two 100 gigabit wavelengths. The T-Series also supports a 500-gigabit coherent line card with five CFP2-ACOs coupled with Ciena's WaveLogic 3 Nano DSP-ASIC.

"We will support higher-capacity wavelengths in a muxponder configuration using our existing S-series," says Xenos. "But for switching applications, switching lower-speed traffic across the shelf onto a very high-capacity wavelength, this is something that the T-series would be used for."

The T-series also adds a denser, larger-degree ROADM, from an existing 6500 S-series 8-degree to a 16-degree flexible grid, colourless, directionless and contentionless (CDC) design. Xenos says the ROADM design is also more compact such that the line amplifiers fit on the same card.

"The requirements of this platform is that it has full integration of layer 0, layer 1 and layer 2 functions," says Xenos.

The 6500 T-series supports open application programming interfaces (APIs) and is being incorporated as part of Ciena's Emulation Cloud. The Emulation Cloud enabling customers to test software on simulated network configurations without requiring 6500 hardware and is being demonstrated at OFC 2016.

The 6500 is also being integrated as part of Ciena's Blue Planet orchestration and management architecture.

SDM and MIMO: An interview with Bell Labs

Part 2: The capacity crunch and the role of SDM

The argument for spatial-division multiplexing (SDM) - the sending of optical signals down parallel fibre paths, whether multiple modes, cores or fibres - is the coming ‘capacity crunch’. The information-carrying capacity limit of fibre, for so long described as limitless, is being approached due to the continual yearly high growth in IP traffic. But if there is a looming capacity crunch, why are we not hearing about it from the world’s leading telcos?

“It depends on who you talk to,” says Peter Winzer, head of the optical transmission systems and networks research department at Bell Labs. The incumbent telcos have relatively low traffic growth - 20 to 30 percent annually. “I believe fully that it is not a problem for them - they have plenty of fibre and very low growth rates,” he says.

Twenty to 30 percent growth rates can only be described as ‘very low’ when you consider that cable operators are experiencing 60 percent year-on-year traffic growth while it is 80 to 100 percent for the web-scale players. “The whole industry is going through a tremendous shift right now,” says Winzer.

In a recent paper, Winzer and colleague Roland Ryf extrapolate wavelength-division multiplexing (WDM) trends, starting with 100-gigabit interfaces that were adopted in 2010. Assuming an annual traffic growth rate of 40 to 60 percent, 400-gigabit interfaces become required in 2013 to 2014, and the authors point out that 400-gigabit transponder deployments started in 2013. Terabit transponders are forecast in 2016 to 2017 while 10 terabit commercial interfaces are expected from 2020 to 2024.

In turn, while WDM system capacities have scaled a hundredfold since the late 1990s, this will not continue. That is because systems are approaching the Non-linear Shannon Limit which estimates the upper limit capacity of fibre at 75 terabit-per-second.

Starting with 10-terabit-capacity systems in 2010 and a 30 to 40 percent core network traffic annual growth rate, the authors forecast that 40 terabit systems will be required shortly. By 2021, 200 terabit systems will be needed - already exceeding one fibre’s capacity - while petabit-capacity systems will be required by 2028.

Even if I’m off by an order or magnitude, and it is 1000, 100-gigabit lines leaving the data centre; there is no way you can do that with a single WDM system

Parallel spatial paths are the only physical multiplexing dimension remaining to expand capacity, argue the authors, explaining Bell Labs’ interest in spatial-division multiplexing for optical networks.

If the telcos do not require SDM-based systems anytime soon, that is not the case for the web-scale data centre operators. They could deploy SDM as soon as 2018 to 2020, says Winzer.

The web-scale players are talking about 400,000-server data centres in the coming three to five years. “Each server will have a 25-gigabit network interface card and if you assume 10 percent of the traffic leaves the data centre, that is 10,000, 100-gigabit lines,” says Winzer. “Even if I’m off by an order or magnitude, and it is 1000, 100-gigabit lines leaving the data centre; there is no way you can do that with a single WDM system.”

SDM and MIMO

SDM can be implemented in several ways. The simplest way to create parallel transmission paths is to bundle several single-mode fibres in a cable. But speciality fibre can also be used, either multi-core or multi-mode.

For the demo, Bell Labs used such a fibre, a coupled 3-core one, but Sebastian Randel, a member of technical staff, said its SDM receiver could also be used with a fibre supporting a few spatial modes. By increasing slightly the diameter of a single-mode fibre, not only is a single mode supported but two second-order modes. “Our signal processing would cope with that fibre as well,” says Winzer.

The signal processing referred to, that restores the multiple transmissions at the receiver, implements multiple input, multiple output or MIMO. MIMO is a well-known signal processing technique used for wireless and digital subscriber line (DSL).

They are garbled up, that is what the rotation is; undoing the rotation is called MIMO

Multi-mode fibre can support as many as 100 spatial modes. “But then you have a really big challenge to excite all 100 spatial modes individually and detect them individually,” says Randel. In turn, the digital signal processing computation required for the 100 modes is tremendous. “We can’t imagine we can get there anytime soon,” says Randel.

Instead, Bell Labs used 60 km of the 3-core coupled fibre for its real-time SDM demo. The transmission distance could have been much longer except the fibre sample was 60 km long. Bell Labs chose the coupled-core fibre for the real-time MIMO demonstration as it is the most demanding case, says Winzer.

The demonstration can be viewed as an extension of coherent detection used for long-distance 100 gigabit optical transmission. In a polarisation-multiplexed, quadrature phase-shift keying (PM-QPSK) system, coupling occurs between the two light polarisations. This is a 2x2 MIMO system, says Winzer, comprising two inputs and two outputs.

For PM-QPSK, one signal is sent on the x-polarisation and the other on the y-polarisation. The signals travel at different speeds while hugely coupling along the fibre, says Winzer: “The coherent receiver with the 2x2 MIMO processing is able to undo that coupling and undo the different speeds because you selectively excite them with unique signals.” This allows both polarisations to be recovered.

With the 3-core coupled fibre, strong coupling arises between the three signals and their individual two polarisations, resulting in a 6x6 MIMO system (six inputs and six outputs). The transmission rotates the six signals arbitrarily while the receiver, using 6x6 MIMO, rotates them back. “They are garbled up, that is what the rotation is; undoing the rotation is called MIMO.”

Demo details

For the demo, Bell Labs generated 12, 2.5-gigabit signals. These signals are modulated onto an optical carrier at 1550nm using three nested lithium niobate modulators. A ‘photonic lantern’ - an SDM multiplexer - couples the three signals orthogonally into the fibre’s three cores.

The photonic lantern comprises three single-mode fibre inputs fed by the three single-mode PM-QPSK transmitters while its output places the fibres closer and closer until the signals overlap. “The lantern combines the fibres to create three tiny spots that couple into a single fibre, either single mode or multi-mode,” says Winzer.

At the receiver, another photonic lantern demultiplexes the three signals which are detected using three integrated coherent receivers.

Don’t do MIMO for MIMO’s sake, do MIMO when it helps to bring the overall integrated system cost down

To implement the MIMO, Bell Labs built a 28-layer printed circuit board which connects the three integrated coherent receiver outputs to 12, 5-gigabit-per-second 10-bit analogue-to-digital converters. The result is an 600 gigabit-per-second aggregate output digital data stream. This huge data stream is fed to a Xilinx Virtex-7 XC7V2000T FPGA using 480 parallel lanes, each at 1.25 gigabit-per-second. It is the FPGA that implements the 6x6 MIMO algorithm in real time.

“Computational complexity is certainly one big limitation and that is why we have chosen a relatively low symbol rate - 2.5 Gbaud, ten times less than commercial systems,” says Randel. “But this helps us fit the [MIMO] equaliser into a single FPGA.”

Future work

With the growth in IP traffic, optical engineers are going to have to use space and wavelengths. “But how are you going to slice the pie?” says Winzer.

With the example of 10,000, 100-gigabit wavelengths, will 100 WDM channels be sent over 100 spatial paths or 10 WDM channels over 1,000 spatial paths? “That is a techno-economic design optimisation,” says Winzer. “In those systems, to get the cost-per-bit down, you need integration.”

That is what the Bell Lab’s engineers are working on: optical integration to reduce the overall spatial-division multiplexing system cost. “Integration will happen first across the transponders and amplifiers; fibre will come last,” says Winzer.

Winzer stresses that MIMO-SDM is not primarily about fibre, a point frequently misunderstood. The point is to enable systems with crosstalk, he says.

“So if some modulator manufacturer can build arrays with crosstalk and sell the modulator at half the price they were able to before, then we have done our job,” says Winzer. “Don’t do MIMO for MIMO’s sake, do MIMO when it helps to bring the overall integrated system cost down.”

Further Information:

Space-division Multiplexing: The Future of Fibre-Optics Communications, click here

For Part 1, click here

Coriant's 134 terabit data centre interconnect platform

“We have several customers that have either purpose-built data centre interconnect networks or have data centre interconnect as a key application riding on top of their metro or long-haul networks,” says Jean-Charles Fahmy, vice president of cloud and data centre at Coriant.

Jean-Charles Fahmy

Jean-Charles Fahmy

Each card in the platform is one rack unit (1RU) high and has a total capacity of 3.2 terabit-per-second, while the full G30 rack supports 42 such cards for a total platform capacity of 134 terabits. The G30's power consumption equates to 0.45W-per-gigabit.

The card supports up to 1.6 terabit line-side capacity and up to 1.6 terabit of client side interfaces. The card can hold eight silicon photonics-based CFP2-ACO (analogue coherent optics) line-side pluggables. For the client-side optics, 16, 100 gigabit QSFP28 modules can be used or 20 QSFP+ modules that support 40 or 4x10 gigabit rates.

Silicon photonics

Each CFP2-ACO supports 100, 150 or 200 gigabit transmission depending on the modulation scheme used. For 100 gigabit line rates, dual-polarisation, quadrature phase-shift keying (DP-QPSK) is used, while dual-polarisation, 8 quadrature amplitude modulation (DP-8-QAM) is used for 150 gigabit, and DP-16-QAM for 200 gigabit.

A total of 128 wavelengths can be packed into the C-band equating to 25.6 terabit when using DP-16-QAM.

It [the data centre interconnect] is a dynamic competitive market and in some ways customer categories are blurring. Cloud and content providers are becoming network operators, telcos have their own data centre assets, and all are competing for customer value

Coriant claims the platform can achieve 1,000 km using DP-16-QAM, 2,000 km using 8-QAM and up to 4,000 km using DP-QPSK. That said, the equipment maker points out that the bulk of applications require distances of a few hundred kilometers or less.

This is the first detailed CFP2-ACO module that supports all three modulation formats. Coriant says it has worked closely with its strategic partners and that it is using more than one CFP2-ACO supplier.

Acacia is one silicon photonics player that announced at OFC 2015 a chip that supports 100, 150 and 200 gigabit rates however it has not detailed a CFP2-ACO product yet. Acacia would not comment whether it is supplying modules for the G30 or whether it has used its silicon photonics chip in a CFP2-ACO. The company did say it is providing its silicon photonics products to a variety of customers.

“Coriant has been active in engaging the evolving ecosystem of silicon photonics,” says Fahmy. “We have also built some in-house capability in this domain.” Silicon photonics technology as part of the Groove G30 is a combination of Coriant’s own in-house designs and its partnering with companies as part of this ecosystem, says Fahmy: “We feel that this is one of the key competitive advantages we have.”

The company would not disclose the degree to which the CFP2-ACO coherent transceiver is silicon photonics-based. And when asked if the different CFP2-ACOs supplied are all silicon photonics-based, Fahmy answered that Coriant’s supply chain offers a range of options.

Oclaro would not comment as to whether it is supplying Coriant but did say its indium-phosphide CFP2-ACO has a linear interface that supports such modulation formats as BPSK, QPSK, 8-QAM and 16-QAM.

So what exactly does silicon photonics contribute?

“Silicon photonics offers the opportunity to craft system architectures that perhaps would not have been possible before, at cost points that perhaps may not have been possible before,” says Fahmy.

Modular design

Coriant has used a modular design for its 1RU card, enabling data centre operators to grow their system based on demand and save on up-front costs. For example, Coriant uses ‘sleds’, trays that slide onto the card that host different combinations of CFP2-ACOs, coherent DSP functionality and client-side interface options.

“This modular architecture allows pay-as-you-grow and, as we like to say, power-as-you-grow,” says Fahmy. “It also allows a simple sparing strategy.”

The Groove G30 uses a merchant-supplied coherent DSP-ASIC. In 2011, NSN invested in ClariPhy the DSP-ASIC supplier, and Coriant was founded from the optical networking arm of NSN. The company will noy say the ratio of DSP-ASICs to CFP2-ACOs used but it is possible that four DSP-ASICs serve the eight CFP2-ACOs, equating to two CFP2-ACOs and a DSP-ASIC per sled.

“Web-scale customers will most probably start with a fully loaded system, while smaller cloud players or even telcos may want to start with a few 10 or 40 gigabit interfaces and grow [capacity] as required,” says Fahmy.

Open interfaces

Coriant has designed the G30 with two software environments in mind. “The platform has a full set of open interfaces allowing the product to be integrated into a data centre software-defined networking (SDN) environment,” says Bill Kautz, Coriant’s director of product solutions. “We have also integrated the G30 into Coriant’s network management and control software: the TNMS network management and the Transcend SDN controller.”

Coriant also describes the G30 as a disaggregated transponder/ muxponder platform. The platform does not support dense WDM line functions such as optical multiplexing, ROADMs, amplifiers or dispersion compensation modules. Accordingly, Groove is designed to interoperate with Coriant’s line-system options.

Groove can also be used as a source of alien wavelengths over third-party line systems, says Fahmy. The latter is a key requirement of customers that want to use their existing line systems.

“It [the data centre interconnect] is a dynamic competitive market and in some ways customer categories are blurring,” says Fahmy. “Cloud and content providers are becoming network operators, telcos have their own data centre assets, and all are competing for customer value.”

Further information

IHS hosted a recent webinar with Coriant, Cisco and Oclaro on 100 gigabit metro evolution, click here

Ovum Q&A: Infinera as an end-to-end systems vendor

Infinera hosted an Insight analyst day on October 6th to highlight its plans now that it has acquired metro equipment player, Transmode. Gazettabyte interviewed Ron Kline, principal analyst, intelligent networks at market research firm, Ovum, who attended the event.

Q. Infinera’s CEO Tom Fallon referred to this period as a once-in-a-decade transition as metro moves from 10 Gig to 100 Gig. The growth is attributed mainly to the uptake of cloud services and he expects this transition to last for a while. Is this Ovum’s take?

Ron Kline, OvumRK: It is a transition but it is more about coherent technology rather than 10 Gig to 100 Gig. Coherent enables that higher-speed change which is required because of the level of bandwidth going on in the metro.

Ron Kline, OvumRK: It is a transition but it is more about coherent technology rather than 10 Gig to 100 Gig. Coherent enables that higher-speed change which is required because of the level of bandwidth going on in the metro.

We are going to see metro change from 10 Gig to 100 Gig, much like we saw it change from 2.5 Gig to 10 Gig. Economically, it is going to be more feasible for operators to deploy 100 Gig and get more bang for their buck.

Ten years is always a good number from any transition. If you look at SONET/SDH, it began in the early 1990s and by 2000 was mainstream.

If you look at transitions, you had a ten-year time lag to get from 2.5 Gig to 10 Gig and you had another ten years for the development of 40 Gig, although that was impacted by the optical bubble and the [2008] financial crisis. But when coherent came around, you had a three-year cycle for 100 gigabit. Now you are in the same three-year cycle for 200 and 400 gigabit.

Is 100 Gig the unit of currency? I think all logic tells us it is. But I’m not sure that ends up being the story here.

If you get line systems that are truly open then optical networking becomes commodity-based transponders - the white box phenomenon - then where is the differentiation? It moves into the software realm and that becomes a much more important differentiator.

Infinera’s CEO asserted that technology differentiation has never been more important in this industry. Is this true or only for certain platforms such as for optical networking and core routers?

If you look at Infinera, you would say their chief differentiator is the PIC (photonic integrated circuit) as it has enabled them to do very well. But other players really have not tried it. Huawei does a little but only in the metro and access.

It is true that you need differentiation, particularly for something as specialised as optical networking. The edge has always gone to the company that can innovate quickest. That is how Nortel did it; they were first with 10 gigabit for long haul and dominated the market.

When you look at coherent, the edge has gone to the quickest: Ciena, Alcatel-Lucent, Huawei and to a certain extent Infinera. Then you throw in the PIC and that gives Infinera an edge.

But then, on the flip side, there is this notion of disaggregation. Nobody likes to say it but it is the commoditisation of the technology; that is certainly the way the content providers are going.

If you get line systems that are truly open then optical networking becomes commodity-based transponders - the white box phenomenon - then where is the differentiation? It moves into the software realm and that becomes a much more important differentiator.

I do think differentiation is important; it always is. But I’m not sure how long your advantage is these days.

Infinera argues that the acquisition of Transmode will triple the total available market it can address.

Infinera definitely increases its total available market. They only had an addressable market related to long haul and submarine line terminating equipment. Now this [acquisition of Transmode] really opens the door. They can do metro, access, mobile backhaul; they can do a lot of different things.

We don’t necessarily agree with the numbers, though, it more a doubling of the addressable market.

The rolling annual long-haul backbone global market (3Q 2014 to 2Q 2015) and the submarine line terminating equipment market where they play [pre-Transmode] was $5.2 billion. If you assume the total market of $14.2 billion is addressable then yes it is nearly a tripling but that includes the legacy SONET/SDH and Bandwidth Management segments which are rapidly declining. Nevertheless, Tom’s point is well-taken, adding a further $5.8 billion for the metro and access WDM markets to their total addressable market is significant.

Tom Fallon also said vendor consolidation will continue, and companies will need to have scale because of the very large amounts of R&D needed to drive differentiation. Is scale needed for a greater R&D spend to stay ahead of the competition?

When you respond to an operator’s request-for-proposal, that is where having end-to-end scale helps Infinera; being able to be a one-stop shop for the metro and long haul.

If I’m an operator, I don’t have to get products from several vendors and be the systems integrator.

Infinera announced a new platform for long haul, the XT-500, which is described as a telecom version of its data centre interconnect Cloud Xpress platform. Why do service providers want such a platform, and how does it differ from cloud Xpress?

Infinera’s DTN-X long haul platform is very high capacity and there are applications where you don’t need a such a large platform. That is one application.

The other is where you lease space [to house your equipment]. If I am going to lease space, if I have a box that is 2 RU (rack unit) high and can do 500 gigabit point-to-point and I don’t need any cross-connect, then this smaller shelf size makes a lot of sense. I’m just transporting bandwidth.

Cloud Xpress is a scaled-down product for the metro. The XT-500 is carrier-class, e.g. NEBS [Network Equipment-Building System] compliant and can span long-haul distances.

Infinera has also announced the XTC-2. What is the main purpose of this platform?

The platform is a smaller DTN-X variant to serve smaller regions. For example you can take a 500 gigabit PIC super-channel and slice it up. That enables you to do a hub-and-spoke virtual ring and drop 100 Gig wavelengths at appropriate places. The system uses the new metro PICs introduced in March. At the hub location you use an ePIC that slices up the 500G into individually routable 100G channels and at the hub location, where the XTC-2 is, you use an oPIC-100.

Does the oPIC-100 offer any advantage compared to existing100 Gig optics?

I don’t think it has a huge edge other than the differentiation you get from a PIC. In fact it might be a deterrent: you have to buy it from Infinera. It is also anti-trend, where the trend is pluggables.

But the hub and spoke architecture is innovative and it will be interesting to see what they do with the integration of PIC technology in Transmode’s gear.

Acquiring Transmode provides Infinera with an end-to-end networking portfolio? Does it still lack important elements? For example, Ciena acquired Cyan and gained its Blue Planet SDN software.

Transmode has a lot of different technologies required in the metro: mobile back-haul, synchronisation, they are also working on mobile front-hauling, and their hardware is low power.

Transmode has pretty much everything you need in these smaller platforms. But it is the software piece that they don’t have. Infinera has a strategy that says: we are not going to do this; we are going to be open and others can come in through an interface essentially and run our equipment.

That will certainly work.

But if you take a long view that says that in future technology will be commoditised, then you are in a bad spot because all the value moves to the software and you, as a company, are not investing and driving that software. So, this could be a huge problem going forward.

What are the main challenges Infinera faces?

One challenge, as mentioned, is hardware commoditisation and the issue of software.

Hardware commodity can play in Infinera’s favour. Infinera should have the lowest-cost solution given its integrated solution, so large hardware volumes is good for them. But if pluggable optics is a requirement, then they could be in trouble with this strategy

The other is keeping up with the Joneses.

I think the 500 Gig in 100 Gig channels is now not that exciting. The 500 Gig PIC is not creating as much advantage as it did before. Where is the 1.2 terabit PIC? Where is the next version that drives Infinera forward?

And is it still going to be 100 Gig? They are leading me to believe it won’t just be. Are they going to have a PIC that is 12 channels that are tunable in modulation formats to go from 100 to 200 to 400 Gig.

They need to if they want to stay competitive with everyone else because the market is moving to 200 Gig and 400 Gig. Our figures show that over 2,000 multi-rate (QPSK and 16-QAM) ports have been shipped in the last year (3Q 2014 to 2Q 2015). And now you have 8-QAM coming. Infinera’s PIC is going to have to support this.

Infinera’s edge is the PIC but if you don’t keep progressing the PIC, it is no longer an edge.

These are the challenges facing Infinera and it is not that easy to do these things.