To efficiency and beyond

Part 3: ROADM and control plane developments

ROADMs and control plane technology look set to finally deliver reconfigurable optical networks but challenges remain.

Operators are assessing how best to architect their networks - from the router to the optical layer - to boost efficiencies and reduce costs. It is developments at the photonic layer that promise to make the most telling contribution to lowering the cost of transport, a necessity given how the revenue-per-bit that carriers receive continues to dwindle.

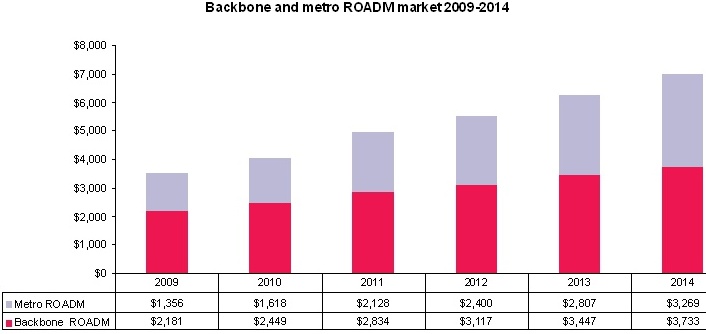

Global ROADM forecast 2009 -14 in US $ miliions Source: Ovum

Global ROADM forecast 2009 -14 in US $ miliions Source: Ovum

“The challenge of most service providers largely hasn’t changed for some time: dealing with growth in demand economically,” says Drew Perkins, CTO of Infinera. “How can operators grow the capacity on each route and switch it, largely on a packet-by-packet basis, without increasing the numbers of dollars going into the network.”

Until now, dynamic optical networking has been conducted at the electrical layer. Electrical switches set up connections within a second, support shared mesh restoration in under 100 milliseconds (ms), and have a proven control plane that oversees networks up to 1,000 networking nodes. This is the baseline performance that a photonic layer scheme will be compared to, says Joe Berthold, vice president of network architecture at Ciena.

AT&T’s Optical Mesh is one such electrically-enable service. Using Ciena’s CoreDirector electrical switches, customers can change their access circuits in SONET STS-1 (50 Megabits-per-second) increments via a web interface. AT&T wants to expand further the capacity increments it places in customers’ hands.

“The real problem with operators today is that it takes way too long to set up a new connection with existing optical infrastructure.”

Tom McDermott, Fujitsu Network Communications

Developments at the photonic layer such as advances in reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexers (ROADMs) as well as control plane and management software complement the electrical layer control. ROADMs enable the redirection of large bandwidths while the electrical layer, with its sub-wavelength grroming and switching at the packet level, accommodates more rapid traffic changes. Operators will benefit as the two layers are used more efficiently.

“The photonic layer is the cheapest per bit per function, cheaper than the transport layer – OTN (Optical Transport Network) or the SONET layer – and the packet layer,” says Brandon Collings, CTO of JDS Uniphase’s consumer and commercial optical products division. “The more efficient, functional and powerful the control plane, the better off operators will be.”

ROADM evolution

ROADMs sit at the core of the network and largely define its properties. “The network’s wavelengths may be 10, 40 or 100 Gig; that is just bolting something on the edge. The ROADM sits in the middle, it’s there, and it has to handle whatever you throw at it,” says Simon Poole, director new business ventures at Finisar.

Operators have gone from using fixed optical add-drop multiplexers (OADMs) to ROADMs with fixed add-drop ports to now colourless and directionless ROADMs. Each step increases the flexibility of the switching devices while reducing the manual intervention required when setting up new lightpaths.

“There has been a much greater drive in the US [for ROADMs] but it is now picking up in Europe”

“There has been a much greater drive in the US [for ROADMs] but it is now picking up in Europe”

Ulf Persson, Transmode Systems

Network architectures also reflect these advances. First ROADMs were typically two-dimensional nodes that enabled metro rings. Now optical mesh networks are possible using the ROADMs’ greater number of interfaces, or degrees.

Transmode Systems has many of its customers – smaller tier one and tier two operators - in Europe, and focusses on the access, metro and metro-regional markets.

“It is not just the type and size of the operators, there are also regional differences in how all-optical and ROADMs are used,” says Ulf Persson, director of network architecture at Transmode. “There has been a much greater drive in the US [for ROADMs] but it is now picking up in Europe.” One reason for limited ROADM demand in Europe, says Persson, is that for smaller networks it is easier to design and predict growth.

Operators with fixed OADMs must plan their networks carefully. When provisioning a service, engineers have to visit and reconfigure the nodes needed to support the new route. In contrast, with fixed add-drop port ROADMs, engineers only need visit the end points.

The end points require manual intervention since the ROADM restricts the lightpath’s direction and wavelength. ROADMs at nodes along the route can at least change the direction but not the lightpath’s wavelength. “You can do the express routing efficiently, it is the [ROADM] drop side that that is not automated at this point,” says Poole.

This still benefits operators even if it doesn’t meet all their optical layer requirements. “Where ROADMs have helped is that while service technicians must visit the end points - connecting the transponder card and client equipment - they save on the intermediate site visits,” says Jörg-Peter Elbers, vice president, advanced technology at ADVA Optical Networking. “Just by a mouse click, you can set up all the nodes in the right configurations without the hassle of doing this manually.”

The result is largely static networks that once set up are seldom changed. “The real problem with operators today is that it takes way too long to set up a new connection with existing optical infrastructure,” says Tom McDermott, distinguished strategic planner, Fujitsu Network Communications.

Colourless and directionless ROADMs aim to solve this. A tunable transponder can now be pointed to any of the ROADM’s network interfaces while exploiting its tunability for the lightpath’s wavelength or colour.

The ROADM percentage of the total metro WDM market. The market comprises Coarse WDM, fixed and reconfigurable OADMs. Source: Ovum

The ROADM percentage of the total metro WDM market. The market comprises Coarse WDM, fixed and reconfigurable OADMs. Source: Ovum

Such colourless and directionless ROADMs offer several benefits. An operator can have several transponders ready for provisioning to meet new service demand. This arrangement for ‘deployment velocity’ has yet to take hold since operators are reluctant to have costly transponders idle, especially if they are 40 and 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) ones.

Colourless and directionless ROADMs will more likely be used for network restoration during maintenance or a fibre cut. This is slow restoration, nowhere near the 100ms associated with electrical signalling; optical signals are analogue and each lightpath must be turned up carefully. “When you re-route an optical signal going more than 1,000km, taking it off one route affects all the other signals on that route and they need to be rebalanced; then putting it on another route, they too need to be rebalanced,” says Infinera’s Perkins. “It is very difficult to manage.”

ADVA Optical Networks cites the example of operators using 1+1 route protection. When one route is down for maintenance, the remaining route is left unprotected. Colourless and directionless ROADMs can be used to set up a spare route during the maintenance. In developing countries, where fibre cuts are more common, 1+N protection can provide operators with redundancy to survive multiple failures. Such a restoration strategy is especially needed if getting to a fault in remote area may take days.

The extra flexibility of the newer ROADMs provide will also aid operators with load balancing, moving traffic away from hotspots as the network grows.

WSSs at the core

The building block at the core of the ROADM is the wavelength-selective switch (WSS). Such switch building-blocks are implemented using light-switching technologies such as liquid crystal, liquid crystal on silicon and MEMS. The WSS routes a lightpath to a particular fibre, with the WSS’s degree in several configurations: 1x2, 1x4, 1x9 and, under development, a 1x23. The ROADM’s degree relates to the network interfaces it supports - a 2-degree ROADM supports two fibre pairs, pointing east and west. A WSS is used for each ROADM degree and hence with each fibre pair.

A 1:9 WSS supports an 8-degree ROADM with the remaining two ports used for local multiplexing and demultiplexing. So far, eight fibre pairs have been sufficient. A 1:23 WSS is being developed to support yet more degrees at a node. For example, more than one fibre pair can be sent in the same direction (doubling a route’s capacity) and for adding extra add-drop banks. JDS Uniphase is one vendor developing a 1:23 WSS.

"Where I’m seeing first interest beyond 1x9 is business service or edge applications - where at a given node point operators need a lot of attachments to different enterprise networks at high capacity multi-wavelength levels,” says Tom Rarick, principal engineer, transport, at Tellabs. “Within infrastructure applications, a 1x9 provides the degree of fibre connectivity necessary; I rarely see beyond a 1x6.”

“The next big thing [after colourless and directionless] is what people call contentionless and gridless, adding yet more flexibility to the optical infrastructure.”

“The next big thing [after colourless and directionless] is what people call contentionless and gridless, adding yet more flexibility to the optical infrastructure.”

Jörg-Peter Elbers, ADVA Optical Networking

For a WSS, the common port connects to the outbound fibre of any given direction, whereas the 9 ports [for a 1:9] face inwards to the centre of the node, says JDSU’s Collings (click here for a JDSU presentation). He describes the WSS as a gatekeeper that determine which lightpaths from which fibres leave a node. As for the incoming fibre, the lightpaths carried are sent to each of the other ROADM node WSSs, one for each direction. “Each WSS selects which channel from which port leaves the node,” says Collings.

To make a ROADM colourless and directionless, extra add-drop ports hardware must be added. These route lightpaths to any node and on any wavelength, or drop any lightpath from any of the other nodes. The add-drop node is built using further WSSs.

One issue still to be resolved is whether WSS sub-system vendors provide all the elements that are added to the WSS to make the ROADM colourless and directionless. “It is not clear whether we should be developing the whole thing or providing the modules for the customers’ line cards and systems,” says Poole.

“The next big thing [after colourless and directionless] is what people call contentionless and gridless, adding yet more flexibility to the optical infrastructure,” says Elbers.(Click here for an ADVA Optical Networking ROADM presentation)

Contentionless refers to avoiding same-wavelength contention. With a colourless and directional ROADM, only one copy of a particular wavelength can be dropped. “With a four-degree node you can have a 96-channel fibre on each,” says Krishna Bala, executive vice president, WSS division at Oclaro. “You may want to drop at the node lambda1 from the east and the same lambda1 coming from the west.” To drop the two, same wavelengths, an extra add-drop block is required.

To make the ROADM fully contentionless, as many add-drop blocks as ROADM degrees are needed. This requires more WSSs, or alternatively 1:N splitters, as well as N:1 selection switches. This way any of the dropped wavelengths from any of the incoming fibres can be routed to any one of the add-drop’s transponders.

“The building blocks for colourless and directionless ROADMs are there; we sell them as a product,” says Elbers, who stresses that the cost of the WSS building block is coming down. But the question remains whether an operator values such network functionality sufficiently to pay. “Without naming names, big carriers are looking at these – they want to have a future-proof, simple-to-plan network,” says Elders.

“It is strictly economics,” agrees Ciena’s Berthold. “We’ve offered a colourless-directionless ROADM for some time. Some buy that but more often they are going for lower cost.”

Gridless

A further ROADM attribute being added to the WSS is gridless even though it will be several years before it is needed. WSS vendors are keen to add the feature – adaptive channel widths - now so that operators’ ROADM deployments will be future-proofed.

“They [WSS vendors] have got to be in a tough spot. They have to invest all that [R&D] money while they [carriers/ system vendors] ask for the world.”

“They [WSS vendors] have got to be in a tough spot. They have to invest all that [R&D] money while they [carriers/ system vendors] ask for the world.”

Ron Kline, Ovum.

Channel bandwidths wider than 50GHz will be needed for line speeds above 100Gbps. Gridless refers to the ability to accommodate lightpaths that do not just fit on the International Telecommunication Union’s (ITU) 50 or 100GHz grid. WSS makers are developing fine pass-band filters that when combined in integer increments form variable channel widths.

“There is a great deal of concern from operators about how they can efficiently use the spectrum to maximize fibre capacity,” says Poole. What operators want is the ability to generate channel bandwidth with much finer granularity and to move away from fixed channel widths.

According to Poole, NTT have demonstrated a ROADM with 12.5GHz increments, others are thinking 25GHz or even 37.5GHz. Finisar says this issue has gained much operator attention in the last six months and that there is urgency for WSS vendors to implement gridless so that any ROADM deployed will be able to support future transmission rates beyond 100Gbps.

“They [WSS vendors] have got to be in a tough spot,” says Ron Kline, principal analyst for network infrastructure at Ovum. “They have to invest all that [R&D] money while they [carriers/ system vendors] ask for the world.”

Coherent receiver technology used for 100Gbps optical transmission will also help enable dynamic optical networking by overcoming technical issues when rerouting paths.

Optical signal distortion in the form of chromatic dispersion and polarisation mode dispersion (PMD) are so much worse at 40Gbps and 100Gbps. Even on 10Gbps routes, where tolerance to dispersion is greater, compensation can be an issue when redirecting a lightpath during network restoration. That is because the alternative route is likely to be longer. Unless the dispersion compensation is correct, there is uncertainty as to whether the alternative link will work, says Ciena’s Berthold.

“With a coherent receiver, you are now independent of dispersion since you can adaptively compensate for dispersion using the [receiver’s] DSP ASIC,” says Berthold. “You no longer have to worry is you have it [the compensation tuning] just right.”

The ASIC can also deliver real-time latency, chromatic dispersion and PMD network measurements at path set-up. This avoids first testing the link, and possible errors when entering measurements in the planning-path network set-up tools. “Coherent technology for 40 Gig and 100 Gig is potentially a game changer in making ROADMs work,” says Berthold.

Coherent digital transponders at 40 and 100Gbps will also drive the deployment of more advanced ROADMs, argues Oclaro. “The need to extract value from the bank of [40 and 100G coherent] transponders in a colourless-directionless sense becomes a lot more important,” says Peter Wigley, director, marketing and technology strategy at Oclaro.

Control plane

Tunable lasers, flexible ROADMS and even coherent technology may be prerequisites for agile optical networks, but another key component is the control plane software. “Many of the networks today have some of the hardware components to make them agile but lack the software,” says Andrew Schmitt, directing analyst, optical, at Infonetics Research. (See ROADM Q&A with Andrew Schmitt.)

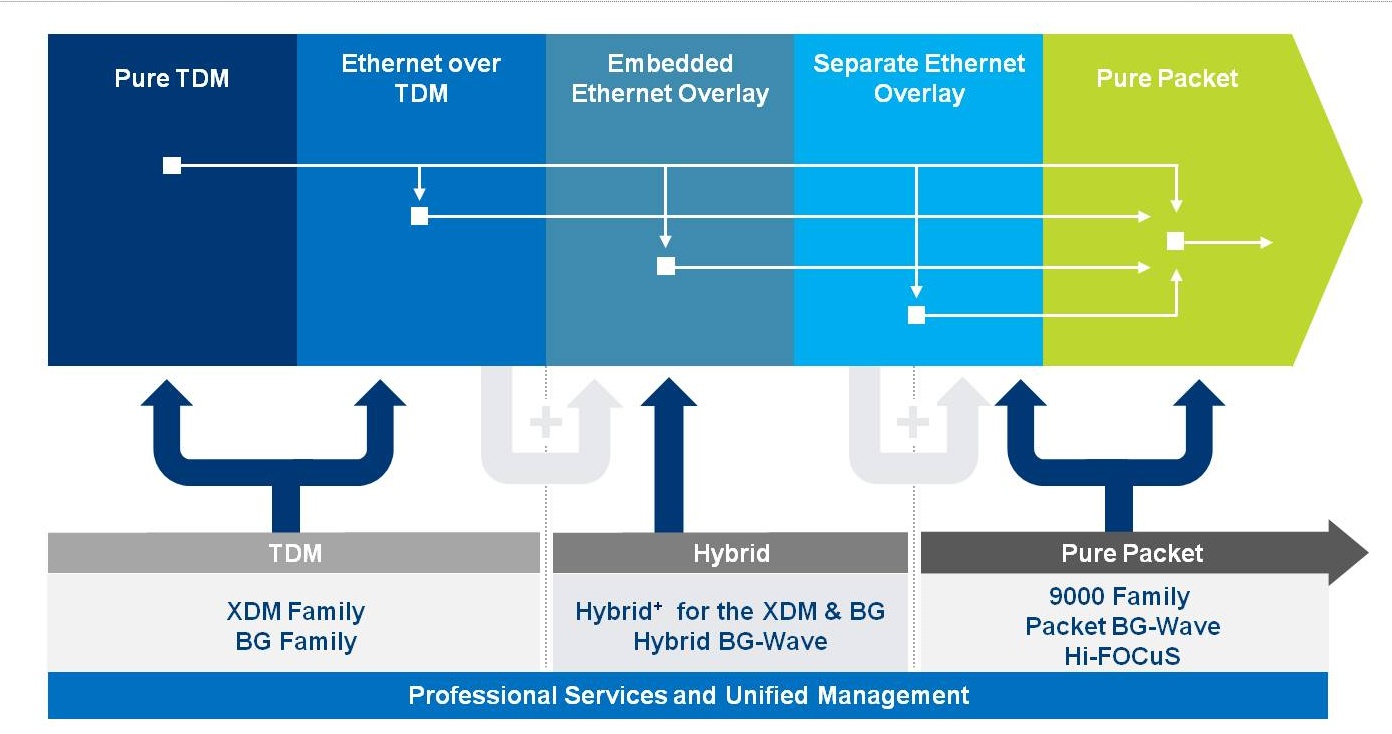

The network can be split into the data plane, used to transport traffic, the control plane that uses routing and signalling protocols to set up connections between nodes, and the management plane that oversees the control plane.

The network can be split into the data plane, used to transport traffic, the control plane that uses routing and signalling protocols to set up connections between nodes, and the management plane that oversees the control plane.

“What is deployed mostly today is a SONET/SDH control plane,” says Tellabs’ Rarick. “This is to manage SONET/SDH ring or mesh networks, using standalone cross-connects or partnered with ROADMs, with the switching primarily done electrically.”

Three industry bodies are advancing control plane technology in several areas including the optical level.

The Internet Engineering Task Force (IEFT) is standardising Generalized Multiprotocol Label Switching (GMPLS) while the ITU is developing control plane requirements and architecture dubbed Automatically Switched Optical Networks (ASON). The third body, the Optical Internetworking Forum (OIF) oversees the implementation efforts.

“The [GMPLS/ASON] control plane comprises a common part and technology-specific part,” says Hans-Martin Foisel, OIF president. The specific technologies include SONET/SDH, OTN, MPLS Transport Profile (MPLS-TP) and the all-optical layer.

"The more efficient, functional and powerful, the control plane, the better off operators will be"

"The more efficient, functional and powerful, the control plane, the better off operators will be"

Brandon Collings, JDS Uniphase.

“Using a control plane with all-optical is a challenge,” says Foisel. “The control plane has to have a very simplified knowledge of the optical parameters.” The photonic layer has numerous optical parameters that can be used. Any protocol needs to streamline the process such that simple rules are used by operators to decide whether a route can be completed or whether signal regeneration is needed.

The IETF is working on wavelength switched optical networks (WSON), the all-optical component of GMPLS, to enable such simplified rules within a single network domain. “GMPLS cannot control wavelengths today using ROADMs and that is what is being standardised in WSON,” says Persson.

What is beyond of scope of WSON is routing transparently between vendors, says Foisel. "It is almost impossible to indentify all the optical parameters in an inter-vendor way for operators to fully use,” says Fujitsu’s McDermott. "You end up with a huge parameter set."

So what will the photonic control plane look like?

“The whole architecture of control will be different that what is done in the electrical domain,” says Berthold. It will combine three main functions. One is embedded intelligence that will learn fibre-route characteristics and optical parameters from the network, data which will use be by each vendor in a proprietary way. Another is a propagation modelling planning tool that will process data offline to determine the viable network paths. These paths will then be preloaded into network elements as well as recommendations as to the preferred ones to use to avoid contention. Finally, use will be made of the signalling to turn these paths up as rapidly as possible. “This is certainly not the same model as electrical,” says Berthold.

By combining electrical and optical switching, operators will be able to continually optimise their networks. “They can devolve their networks to the lowest cost and most power-efficient solution,” says Berthold.

Ciena, for example, is adding colourless-directionless ROADMs to its 3.6 terabit-per-second 5430 electrical switch. “When you start growing traffic from a low level you need electrical switches in many places in order to efficiently fill wavelengths,” says Berthold. “But as traffic grows there is more opportunity to bypass intermediate nodes with an optical path.” By tying the ROADM with the electric switch, traffic can be regroomed and electrical paths set up on-demand to continually optimise the network.

Challenges

Despite progress in ROADM hardware and control plane management, challenges remain before a remotely controlled all-ROADM mesh network will be achieved.

One is handling customer application rates at 1, 10 and 40Gbps on 100 Gbps infrastructure. This will use the OTN protocol and will require electrical switch and control plane support.

Interoperability between vendors’ equipment must also be demonstrated. “Interlayer management – it is not enough just to do optical,” says Kline. “And it is not only between layers but interoperability between vendors’ equipment.” Thus, even if Verizon Business is correct that colourless, directionless ROADMs will become generally available in 2012; the vision of a dynamic optical network will take longer.

“Coherent technology for 40 Gig and 100 Gig is potentially a game changer in making ROADMs work”

“Coherent technology for 40 Gig and 100 Gig is potentially a game changer in making ROADMs work”

Joe Berthold, Ciena

“GMPLS/ASON are still years out and some operators may never deploy them,” says Schmitt at Infonetics. But Kline highlights the vendors Huawei and Alcatel-Lucent as keen promoters of control-plane-enabled dynamic optical networking.

“Huawei has 250 ASON applications with over 80 carriers, and 30-plus OTN WDM ASON applications,” says Kline. Here, an ASON application is described a ring or nodes that use a control plane for automated networking. “These are small and self-contained; not AT&T’s and Verizon’s [sized] meshed networks,” says Kline, who adds that Alcatel-Lucent also has such ASON deployments.

There are also business-case hurdles associated with photonic switching to be overcome.

Doing things on-demand may be compelling but need to be proven, says Jim King, executive director of new technology product development and engineering at AT&T Labs. This is easier to prove deeper in the network. “In the middle of the network it is easy because the law of large numbers means I know I need lots of capacity out of Chicago, say; I just don’t know whether it needs to go north, east or south,” says King. “But when a just-in-time delivery requirement extends to the end of the network, the financials are much more challenging based on how close you need to get to customer premises, cell towers or critical customer data centres.”

What next?

Oclaro too believes that it will be another two years before colourless, directionless and contentionless ROADMs start to be deployed in volume. The challenge thereafter is driving down their cost.

Another development that is likely to emerge after gridless is faster switching speeds to reduce network latency. Operators are using their mesh networks for restoration but there is a growing interest in protection and restoration at the optical layer, says Bala. “We were seeing RFPs (request-for-proposals) where a WSS of below 2s was ok,”’ he says. “Now it is: ‘How fast can you switch?’ and “Can you switch below 100ms’.”

This is driving interest in optical channel monitoring. “Ultimately it will require the ability to monitor the ROADM ports from signal power and to detect contention, and you’ll need to do this quickly,” says Wigley. “It is not very useful having a fast WSS unless you know quickly where the traffic is going.”

Technology will continue to provide incremental enhancements. The cost-per-bit-per-kilometer has come down six or seven orders of magnitude in the last two decade, says Finisar’s Poole. Apart from the erbium-doped fibre amplifier (EDFA), no single technology has made such a sizable contribution. Rather it has been a sequence of multiple incremental optimisations. “Coherent technology is one way of getting more data down a pipe; gridless is another to get a 2x improvement down a pipe,” says Poole. “Each of these is incremental, but you have to keep doing these steps to drive the cost-per-bit down.”

Meanwhile operators will look to further efficiencies to keep driving down transport costs. “Operators are looking at tradeoffs of router versus optical switching,” says McDermott. “They are going through various tradeoffs, the new services they might offer, and what is a flexible but cost effective solution.” As yet there is no universal agreement, he says.

“The balance between the two [the optical and electrical layer] is the key,” says Infinera’s Perkins. “There is a balance you have to reach to achieve the best economics: the lowest cost network supporting the highest capacity possible at a cost you can afford, and operate it with the fewest people.”

And ROADMs will be deployed more widely. “In 3-5 years’ time everything will have a ROADM in it – it better have a ROADM in it,” says Kline. At the electrical layer it will be Ethernet and at the optical it will be OTN and lightpaths. “It is all about simplification and saving costs.”

Other dynamic optical network briefing sections

Part 1: Still some way to go

Part 2: ROADMS: reconfigurable but still not agile

Reflecting light to save power

System vendors will be held increasingly responsible for the power consumption of their telecom and datacom platforms. That’s because for each watt the equipment generates, up to six watts is required for cooling. It is a burden that will only get heavier given the relentless growth in network traffic.

"Enterprises are looking for huge capacity at low cost and are increasingly concerned about the overall impact on power consumption"

"Enterprises are looking for huge capacity at low cost and are increasingly concerned about the overall impact on power consumption"

David Smith, CIP Technologies

No surprise, then, that the European 7th Framework Programme has kicked-off a research project to tackle power consumption. The Colorless and Coolerless Components for Low-Power Optical Networks (C-3PO) project involves six partners that include component specialist CIP Technologies and system vendors ADVA Optical Networking.

CIP is the project’s sole opto-electronics provider while ADVA Optical Networking's role is as system integrator.

“It’s not the power consumption of the optics alone,” says David Smith, CTO of CIP Technologies. “The project is looking at component technology and architectural issues which can reduce overall power consumption.”

The data centre is an obvious culprit, requiring up to 5 megawatts. Power is consumed by IT and networking equipment within the data centre – not a C-3PO project focus – and by optical networking equipment that links the data centre to other sites. “Large enterprises have to transport huge amounts of capacity between data centres, and requirements are growing exponentially,” says Smith. “They [enterprises] are looking for huge capacity at low cost and are increasingly concerned about the overall impact on power consumption.”

One C-3PO goal is to explore how to scale traffic without impacting the data centre’s overall power consumption. Conventional dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) equipment isn’t necessarily the most power-efficient given that DWDM tunable lasers requires their own cooling. “There is the power that goes into cooling the transponder, and to get the heat away you need to multiply again by the power needed for air conditioning,” says Smith.

Another idea gaining attention is operating data centres at higher ambient temperatures to reduce the air conditioning needed. This idea works with chips that have a wide operating temperature but the performance of optics - indium phosphide-based actives - degrade with temperature such that extra cooling is required. As such, power consumption could even be worse, says Smith

A more controversial optical transport idea is changing how line-side transport is done. Adding transceivers directly to IP core routers saves on the overall DWDM equipment deployed. This is not a new idea, says Smith, and an argument against this is it places tunable lasers and their cooling on an IP router which operates at a relatively high ambient temperature. The power reduction sought may not be achieved.

But by adopting a new transceiver design, using coolerless and colourless (reflective) components, operating at a wider temperature range without needing significant cooling is possible. “It is speculative but there is a good commercial argument that this could be effective,” says Smith.

C-3PO will also exploit material systems to extend devices’ temperature range - 75oC to 85oC - to eliminate as much cooling as possible. Such material systems expertise is the result of CIP’s involvement in other collaborative projects.

"If the [WDM-PON] technology is deployed on a broad scale - that is millions of user lines – every single watt counts"

Klaus Grobe, ADVA Optical Networking

Indeed a companion project, to be announced soon, will run alongside C-3PO based on what Smith describes as ‘revolutionary new material systems’. These systems will greatly improve the temperature performance of opto-electronics. “C-3PO is not dependent on this [project] but may benefit from it,” he says.

Colourless and coolerless

CIP’s role in the project will be to integrate modulators and arrays of lasers and detectors to make coolerless and colourless optical transmission technology. CIP has its own hybrid optical integration technology called HyBoard.

“Coolerless is something that will always be aspirational,” says Smith. C-3PO will develop technology to reduce and even eliminate cooling where possible to reduce overall power consumption. “Whether you can get all parts coolerless, that is something to be strived for,” he says.

Colourless implies wavelength independence. For light sources, one way to achieve colourless operation is by using tunable lasers, another is to use reflective optics.

CIP Technologies has been working on reflective optics as part of its work on wavelength division multiplexing, passive optical networks (WDM-PON). Given such reflective optics work for distances up to 100km for optical access, CIP has considered using the technology for metro and enterprise networking applications.

Smith expects the technology to work over 200-300km, at data rates from 10 to 28 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) per channel. Four 28Gbps channels would enable low-cost 100Gbps DWDM interfaces.

Reflective transmission

CIP’s building-block components used for colourless transmission include a multi-wavelength laser, an arrayed waveguide grating (AWG), reflective modulators and receivers (see diagram).

Reflective DWDM architecture. Source: CIP Technologies

Reflective DWDM architecture. Source: CIP Technologies

Smith describes the multi-wavelength laser as an integrated component, effectively an array of sources. This is more efficient for longer distances than using a broadband source that is sliced to create particular wavelengths. “Each line is very narrow, pure and controlled,” says Smith.

The laser source is passed through the AWG which feds individual wavelengths to the reflective modulators where they are modulated and passed back through the AWG. The benefit of using a reflective modulator rather than a pass-through one is a simpler system. If the light source is passed through the modulator, a second AWG is needed to combine all the sources, as well as a second fibre. Single-ended fibre is also simpler to package.

For data rates of 1 or 2Gbps, the reflective modulator used can be a reflective semiconductor optical amplifier (RSOA). At speeds of 10Gbps and above, the complementary SOA-REAM (reflective electro-absorption modulator) is used; the REAM offers a broader bandwidth while the SOA offers gain.

The benefit of a reflective scheme is that the laser source, made athermal and coolerless, consumes far less power than tunable lasers. “It has to be at least half the cost and we think that is achievable,” says Smith.

Using the example of the IP router, the colourless SFP transceiver – made up of a modulator and detector - would be placed on each line card. And the multi-wavelength laser source would be fed to each card’s module.

Another part of the project is looking at using arrays of REAMs for WDM-PON. Such an modulator array would be used at the central office optical line terminal (OLT). “Here there are real space and cost savings using arrays of reflective electro-absorption modulators given their low power requirements,” says Smith. “If we can do this with little or no cooling required there will be significant savings compared to a tunable laser solution.”

ADVA Optical Networking points out that with an 80-channel WDM-PON system, there will be a total of 160 wavelengths (see the business case for WDM-PON). “If you consider 80 clients at the OLT being terminated with 80 SFPs, there will be a cost, energy consumption and form-factor overkill,” says Klaus Grobe, senior principal engineer at ADVA Optical Networking. “The only known solution for this is high integration of the transceiver arrays and that is exactly what C-3PO is about.”

The low-power aspect of C-3PO for WDM-PON is also key. “In next-gen access, it is absolutely vital,” says Grobe. “If the technology is deployed on a broad scale - that is millions of user lines – every single watt counts, otherwise you end up with differences in the approaches that go into the megawatts and even gigawatts.”

There is also a benchmarking issue: the WDM-PON OLT will be compared to the XG-PON standard, the next-generation 10Gbps Gigabit passive optical network (GPON) scheme. Since XG-PON will use time-division multiplexing, there will be only one transceiver at the OLT. But this is what a 40- or 80-channel WDM-PON OLT will be compared with.

There is also a benchmarking issue: the WDM-PON OLT will be compared to the XG-PON standard, the next-generation 10Gbps Gigabit passive optical network (GPON) scheme. Since XG-PON will use time-division multiplexing, there will be only one transceiver at the OLT. But this is what a 40- or 80-channel WDM-PON OLT will be compared with.

CIP will also be working closely with 3-CPO partner, IMEC, as part of the design of the low-power ICs to drive the modulators.

Project timescales

The C-3PO project started in June 2010 and will last three years. The total funding of the project is €2.6 million with the European Union contributing €1.99 million.

The project will start by defining system requirements for the WDM-PON and optical transmission designs.

At CIP the project will employ the equivalent of two full-time staff for the project’s duration though Smith estimates that 15 CIP staff will be involved overall.

ADVA Optical Networking plans to use the results of the project – the WDM-PON and possibly the high-speed transmission interfaces - as part of its FSP 3000 WDM platform.

CIP expects that the technology developed as part of 3-CPO will be part of its advanced product offerings.

BroadLight’s GPON ICs: from packets to apps

BroadLight has announced its Lilac family of customer premise equipment (CPE) chips that support the Gigabit Passive Optical Network (GPON) standard.

The company claims its GPON devices with be the first to be implemented using a 40nm CMOS process. The advanced CMOS process, coupled with architectural enhancements, will double the devices' processing performance while improving by five-fold the packet-processing capability. The devices also come with a hardware abstraction layer that will help system vendors tailor their equipment.

"Traffic models and service models are not stable, and there are a lot of differences from carrier to carrier"

Didi Ivancovsky, BroadLight

Lilac will also act as a testbed for technologies needed for XG-PON, the emerging next generation GPON standard. XG-PON will support a 10 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) downstream and 2.5Gbps upstream rate, and is set for approval by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in September.

Why is this important?

GPON networks are finally being rolled out by carriers after a slow start. Yet the GPON chip market is already mature; Lilac is BroadLight’s third-generation CPE family.

Major chip vendors such as Broadcom and Marvell are also now competing with the established GPON chip suppliers such as BroadLight and PMC-Sierra. “The [big] gorillas are entering [the market],” says Didi Ivancovsky, vice president of marketing at BroadLight.

BroadLight claims it has 60% share of the GPON CPE chip market. For the central office, where the optical line terminal (OLT) GPON integrated circuits (ICs) reside, the market is split between 40% merchant ICs and 60% FPGA-based designs. BroadLight claims it has over 90% of the OLT merchant IC market.

The Lilac family is Broadlight’s response to increasing competition and its attempt to retain market share as deployments grow.

GPON market

US operator Verizon with its FiOS service remains the largest single market in terms of day-to-day GPON deployments. But now significant deployments are taking place in Asia.

“Verizon might still be the largest individual deployer, but China Telecom and China Mobile are catching up fast,” says Jeff Heynen, directing analyst, broadband and video at Infonetics Research. “In fact, the aggregate GPON market in China is now larger than what Verizon has been deploying, given that Verizon’s OLT numbers have really slowed while its optical network terminal (ONT) shipments remain high at some 200,000 per quarter.”

“Verizon might still be the largest individual deployer, but China Telecom and China Mobile are catching up fast”

Jeff Heynen, Infonetics Research

Chinese operators are deploying both GPON and Ethernet PON (EPON) technologies. According to BroadLight, Chinese carriers are moving from deploying multi-dwelling unit (MDU) systems to single family unit (SFU) ONTs.

An MDU deployment involves bringing PON to the basement of a building and using copper to distribute the service to individual apartments. However such deployments have proved less popular that expected such that operators are favouring an ONT-per-apartment.

“Through this transition, China Telecom and China Unicom are also making the transition to GPON,” says Ivancovsky. “End–to-end prices of EPON and GPON are practically the same,” GPON has a download speed of 2.5Gbps and an upload speed of 1.25Gbps (Gbps) while for EPON it is 1.25Gbps symmetrical.

China Telecom and China Unicom are deploying GPON is several provinces whereas in major population centres the PON technology is being left unspecified; vendors can propose either the use of EPON or GPON. “This is a big change, really a big change,” says Ivancovsky.

In India, BSNL and a handful of private developers have been the primary GPON deployers, though the Indian market is still in its infancy, says Heynen. Ericsson has also announced a GPON deployment with infrastructure provider Radius Infratel that will involve 600,000 homes and businesses.

“I expect there to be a follow-on tender for BSNL later this year or early next year that will be twice the size of the first tender of 700,000 total GPON lines,” says Heynen. He also expects MTNL to begin deploying GPON early next year.

In other markets, Taiwan’s Chunghwa Telecom has issued its first tender for GPON. Telekom Malaysia is deploying GPON as is Hong Kong Broadband Network (HKBN), while in Australia the National Broadband Network Company will roll-out a 100Mbps fibre-to-the-home network to 90% of Australian premises over eight years working with Alcatel-Lucent.

“Let’s not forget about Europe, which has been basically dormant from a GPON perspective,” adds Heynen. “We now have commitments from France Telecom, Deutsche Telekom, and British Telecom to roll out more FTTH using GPON, which should help increase the overall market, which really was being driven by Telefonica, Portugal Telecom, and Eitsalat.”

Infonetics expects 2010 to be the first year that GPON revenue will exceed EPON revenue: US $1.4 billion worldwide compared to $1.02 billion. By 2014, the market research firm expects GPON revenue to reach $2.5 billion with EPON revenue - 1.25Gbps and 10Gbps EPON - to be US $1.5 billion. “At this point, China, Japan, and South Korea will be the only major EPON markets with many MSOs also using EPON for FTTH and business services,” says Heynen.

What’s been done?

BroadLight offers a range of devices in the Lilac family. It has enhanced the control processing performance of the CPE devices using 40nm CMOS, and has also added more network processor unit (NPU) cores to enhance the ICs’ data plane processing performance.

“It’s been the same story for some time now,” says Heynen. “System-on-chip vendors differentiate themselves on four key aspects: footprint, power consumption, speed and, most importantly, cost”

A key driver for upping the Lilac family’s control processor’s performance is to support the Java programming language and the OSGi Framework, says Ivancovsky. The OSGi Framework used with embedded systems has yet to be deployed on gateways but is becoming mandatory. This will enable the CPE gateway to run downloaded applications much as applications stores now complement mobile handsets.

BroadLight has also doubled to four the on-chip RunnerGrid NPU cores. “Traffic models and service models are not stable, and there are a lot of differences from carrier to carrier” says Ivancovsky. “This [on-chip] flexibility helps us to have a single device that can support many different requirements.”

As an example, Broadlights cites South Korean operator, SK Broadband, which is deploying an ONT supporting two gigabit Ethernet (GbE) ports – one for laptops and the other for the home’s set-top box. Thus a single GPON 2.5Gbps stream is delivered down the fibre and shared between the PON’s 32 or 64 ONTs, with each ONT having two 1GbE links.“The carrier wants to limit the IPTV downstream rate according to the service level agreement,” says Ivancovsky. Having the network processor as part of the CPE, the carrier can avoid deploying more more expensive NPUs at the central office.

The overall result is a Lilac family rated at 2,000 Dhrystone MIPS (DMIPS) and a packet processing capability of 15 million packets per second (Mpps) compared to BroadLight’s current-generation CPE family of 650-900 DMIPs and 3Mpps.

“Broadlight understands that you have to have a range of chips that provide flexibility across a wide range of CPE and infrastructure types,” says Heynen. The CPE demands of a Verizon differ markedly from those of China Telecom, for example, primarily because average-revenue-per-user expectations are so different. Verizon wants to provide the most advanced integrated CPE, with the ability to do TR-069 remote provisioning and both broadcast and on-demand TV, while China Telecom is concerned with achieving sustained downstream bandwidth, with IPTV being a secondary concern, he says.

Heynen also highlights the devices’ software stack with its open application programming interfaces (APIs) that allow third-party developers to develop applications on top of features already provided in BroadLight’s software stack.

“Residential gateway software stacks used to be dominated by Jungo (NDS). But now chipset companies are developing their own, which helps to reduce licensing costs on a per CPE basis,” says Heynen. “If a silicon vendor can provide a hardware abstraction layer like this, it makes it very attractive to system vendors who need an easy way to customise feature sets for a wide range of customers.”

Is the Lilac GPON family fast enough to support XG-PON?

“We are deep in the design of XG-PON end-to-end: one team is working on the OLT and one on the ONT,” says Ivancovsky. “We expect an FPGA prototype very early in 2011.”

The first XG-PON product will be an OLT ASIC rated at 40Gbps: supporting four XG-PON or 16 GPON ports. One XG-PON challenge is developing a 10Gbps SERDES (serialiser/ deserialiser), says Ivancovsky: “The SERDES in Lilac is a 10Gbps one, a preparation for XG-PON devices.”

Meanwhile, the first XG-PON CPE design will be implemented using an FPGA but the control processor used will be the one used for Lilac. As for data plane processing, NPUs will be added to the OLT design while more NPUs cores will be needed within the CPE device. “The number of cores in the Lilac will not be enough; we are talking about 40Gbps,” says Ivancovsky.

Lilac device members

Ivancovsky highlights three particular devices in the Lilac family that will start appearing from the fourth quarter of this year:

- The BL23530 aimed at GPON single family units with VoIP support. To reduce its cost, a low-cost packaging will be used.

- The BL23570 which is aimed at the integrated GPON gateway market.

- The BL23510, a compact 10x10mm IC to be launched after the first two. The chip’s small size will enable it to fit within an SFP form-factor transceiver. The resulting SFP transceiver can be added to connect a DSLAM platform, or upgrade an enterprise platform, to GPON.

“This new system-on-chip is a technology improvement, especially with respect to the residential gateway software layer, which is a requirement among most operators,” concludes Heynen. “But it should be noted this is an addition to, not a replacement for, existing BroadLight chips that solve different infrastructure requirements.”

ROADMS: When "-less" is more

One only has to look at neighbouring IT and cloud computing in particular with its PaaS, IaaS and SaaS (Platform-, Infrastructure- and Software-as-a-Service).

But when it comes to agile optical networking and the reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexer (ROADM), what is notable is the smarts that are being added and yet all are described using the “-less” suffix: colourless, directionless, contentionless and gridless.

These are all logical names once the enhancements they add are explained. But as Infonetics Research analyst Andrew Schmitt has pointed out, the industry could do better with its naming schemes. Even the most gifted sales person may be challenged selling the merits of a colourless, directionless product.

Colourless is a term long in use for such optical devices as arrayed-waveguide gratings. So to expect the industry to change now is perhaps unrealistic. But could better names be chosen? And does it matter?

Well, yes, if it undersells the benefits new products deliver.

The four smarts

Colourless refers to the decoupling of the wavelength dependency, so is “wavelength independent” better? What about colourful? Sales people are on a better footing already.

Then there is directionless. The idea here is that the latest ROADMs have full flexibility in routing a lightpath to any of the network interface ports. So instead of directionless, what about ROADMs that are omnidirectional or all-directional?

"Even the most gifted sales person may be challenged selling the merits of a colourless, directionless product."

Contentionless means non-blocking, a well-known term widely used to describe switch and router designs.

And gridless comes from the concept of relaxing the rigid ITU grid for wavelengths. Again, a perfectly logical name. But it sells short the adaptive channel widths that new ROADMs will support for data rates above 100 Gigabit-per-second.

So third-generation ROADMs are colourless, directionless, contentionless and gridless products. But does colourful, all-directional, non-blocking and adaptive-channel ROADMs sound better?

Suggestions welcome.

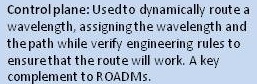

Wireless backhaul: The many routes to packet

ECI Telecom has detailed its wireless backhaul offering that spans the cell tower to the metro network. The 1Net wireless backhaul architecture supports traditional Sonet/SDH to full packet transport, with hybrid options in between, across various physical media.

“We can support any migration scheme an operator may have over any type of technology and physical medium, be it copper, fibre or microwave,” says Gil Epshtein, senior product marketing manager, network solutions division at ECI Telecom.

Why is this important?

Operators are experiencing unprecedented growth in wireless data due to the rise of smart phones and notebooks with 3G dongles for mobile broadband.

Mobile data surpassed voice traffic for the first time in December 2009, according to Ericsson, with the crossover occurring at approximately 140,000 terabytes per month in both voice and data traffic. According to Infonetics Research, mobile broadband subscribers surpassed digital subscriber line (DSL) subscribers in 2009, and will grow to 1.5 billion worldwide in 2014. By then, there will be 3.6 exabytes (3.6 billion gigabytes) per month of mobile data traffic, with two thirds being wireless video, forecasts Cisco Systems.

“The challenge is that almost all the growth is packet internet traffic, and that is not well suited to sit on the classic TDM backhaul network originally designed for voice,” says Michael Howard, principal analyst, carrier and data center networks at Infonetics Research. TDM refers to time division multiplexing based on Sonet/SDH where for wireless backhaul T1/E1lines are used.

“There is a gap between the technology hype and real life”

Gil Epshtein, ECI Telecom

The fast growth also implies an issue of scale, with the larger mobile operators having many cell sites to backhaul. E1/TI lines are also expensive even if prices are coming down, says Howard: “It is much cheaper to use Ethernet as a transport – the cost per bit is enormously better.”

This is why operators are keen to upgrade their wireless backhaul networks from Sonet/SDH to packet-based Ethernet transport. “But there is a gap between the technology hype and real life,” says Epshtein. Operators have already invested heavily in existing backhaul infrastructure and upgrading to packet will be costly. The operators also know that projected revenues from data services will not keep pace with traffic growth.

“Operators are faced with how to build out their backhaul infrastructures to meet service demands at cost points that provide an adequate return on investment,” says Glen Hunt, principal analyst, carrier transport and routing at Current Analysis. Such costs are multi-faceted, he says, on the capital side and the operational side. “Carriers do not want to buy an inexpensive device that adds complexity to network operations which then offsets any capital savings.”

“It is much cheaper to use Ethernet as a transport –the cost per bit is enormously better.”

Michael Howard, Infonetics Research

To this aim, ECI offers operators a choice of migration schemes to packet-based backhaul. Its solution supports T1/E1lines and Ethernet frame encapsulation over TDM, Ethernet overlay networks, and packet-only networks (see chart above).

With Ethernet overlay, an Ethernet network runs alongside the TDM network. The two can co-exist within a common network element, what ECI calls embedded Ethernet overlay, or separately using distinct TDM and packet switch platforms. And when an operator adopts all-packet, legacy TDM traffic can be carried over packets using circuit emulation pseudo-wire technology.

“ECI’s offering is significant since it includes all the components and systems necessary to handle nearly any type of backhaul requirement,” says Hunt. The same is true for most of the larger system vendors, he says. However, many vendors integrate third party devices to complete their solutions – ECI itself has done this with microwave. But with 1NET for wireless backhaul, ECI will now offer its own microwave backhaul systems.

According to Infonetics, between 55% and 60% of all backhaul links are microwave outside of North America. And 80% of all microwave sales are for mobile backhaul. Moreover, Infonetics estimates that 70 to 80% of operator spending on mobile backhaul through 2012 will be on microwave. “Those are the figures that explain why ECI has decided to go it alone,” says Howard. Until now ECI has used products from its microwave specialist partner, Ceragon Networks.

“ECI has all the essential features that the other big players have like Ericsson, Alcatel-Lucent, Nokia Siemens Networks and Huawei,” says Howard. What is different is that ECI does not supply radio access network (RAN) equipment such as basestations. “It is ok, though, because almost all of the [operator] backhaul tenders separate between RAN and backhaul,” says Howard.

ECI argues that by adopting a technology-agnostic approach, it can address operators’ requirements without forcing them down a particular path. “Operators are looking for guidance as to which path is best from this transition,” says Epshtein. There is no one-model fits all. “We have so many exceptions you really need to look on a case-by-case basis.”

In developed markets, for example, the building of packet overlay is generally happening faster. Some operators with fixed line networks have already moved to packet and that, in theory, simplifies upgrading the backhaul to packet. But organisational issues across an operator’s business units can complicate and delay matters, he says.

And Epshtein cites one European operator that will use its existing network to accommodate growth in data services over the coming years: “It is putting aside the technology hype and looking at the bottom line."

In emerging markets, moving to packet is happening more slowly as mobile users’ income is limited. But on closer inspection this too varies. In Africa, certain operators are moving straight to all-IP, says Ephstein, whereas others are taking a gradual approach.

What’s been done?

ECI has launched new products as well as upgraded existing ones as part of its 1NET wireless backhaul offering.

The company has announced its BG-Wave microwave systems. There are two offerings: an all-packet microwave system and a hybrid one that supports both TDM and Ethernet traffic. ECI says that having its own microwave products will allow it to gain a foothold with operators it has not had design wins before.

“ECI will need to prove the value of its microwave products with actual field deployments”

Glen Hunt, Current Analysis

ECI has announced two additional 9000 carrier Ethernet switch routers (CESR) families: the 9300 and 9600. These have switching capacities and a product size more suited to backhaul. The switches support Layer 3 IP-MPLS and Layer 2 MPLS-TP, as well as the SyncE and IEEE 1588 Version 2 synchronisation protocols.

ECI has also upgraded its XDM multi-service provisioning platform (MSPP) to enable an embedded overlay with Ethernet and TDM traffic supported within the platform.

“When an operator is choosing to add packet backhaul to existing TDM backhaul, typically it is a separate network – they keep voice on TDM and add a second network for packet,” says Howard. This hybrid approach involves adding another set of equipment. “ECI has added functions to existing equipment, which operators may already have, that allows two networks to run over a single set of products.”

Also included in the solution are ECI’s BroadGate and its Hi-FOCuS multi-service access node (MSAN). This is not for operators to deploy the platform for wireless backhaul but rather those operators that have the MSAN can now use it for backhauling traffic, says Ephstein. This is useful in dense urban areas and for operators offering wholesale services to other operators.

All the network elements are controlled using ECI’s LightSoft management system.

“ECI’s solution has the advantage that all the systems use the same operating system and support the same features,” says Hunt. He cites the example of MPLS-TP which is implemented on ECI’s carrier Ethernet and optical platforms.

“ECI has a full range of platforms that all work together to meet the needs of mobile as well as fixed operator,” says Hunt. “ECI will need to prove the value of its microwave products with actual field deployments.”

Operator interest

ECI has secured general telecom wins with large incumbent operators in Western Europe and has been winning business in Eastern Europe, Russia, India and parts of Asia.

ECI’s sweet spot has been its relationship with Tier 2 and Tier 3 operators, says Hunt, and since the company offers broadband access, optical transport, and carrier Ethernet, it can use these successes to help expand into areas such as wireless backhaul.

But wireless backhaul is already a key part of the company’s business, accounting for over 30% of revenues, says Ephstein. Late last year ECI estimated that it was carrying between 30% and 40% of the mobile backbone traffic in India, a rapidly growing market.

As for 1NET wireless backhaul, ECI has announced one win so far - Israeli mobile operator Cellcom which has selected the 9000 CESR family. “Cellcom shows that ECI can continue to expand its presence in the network - in this case leveraging business Ethernet services to add backhaul,” says Hunt.

In addition one European operator, as yet unnamed, has selected ECI’s embedded overlay. “Several other operators are in various stages of selecting the right option for them,” says Ephstein.

- For some ECI wireless backhaul papers and case studies, click here

Ten years gone: Optical components after the boom

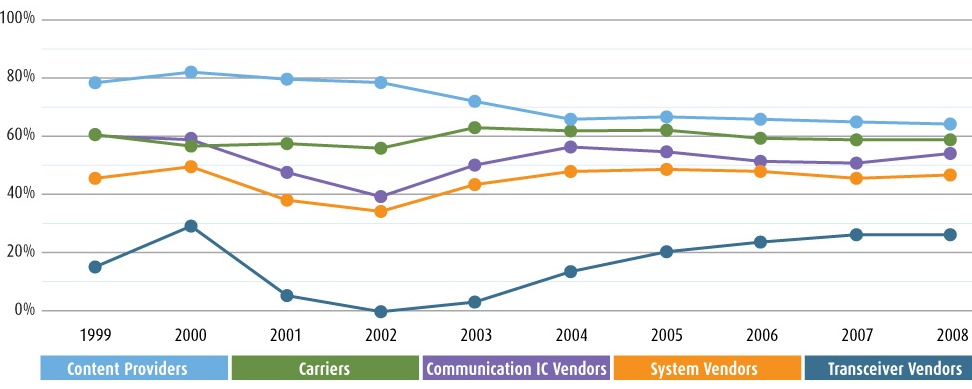

Average gross margin by industry. Source: LightCounting

Average gross margin by industry. Source: LightCounting

The biggest change in the last decade has been the way optics is perceived. That is the view of Vladimir Kozlov, boss of optical transceiver market research firm, LightCounting. “In 2000, optics was set to change the world,” he says. “The intelligent optical network would do all the work for the carrier; nothing would be done electrically.”

The boom of 1999-2000 saw hundreds of start-ups enter the market. Ten years on and a handful only remain; none changed the industry dramatically.

“The worse is definitely behind us”

“The worse is definitely behind us”

Vladimir Kozlov, LightCounting

Kozlov cites tunable lasers as an example. In 2000, the CEO of one start-up claimed the market for tunable lasers would grow to US$1 billion. Today the tunable laser market is worth several tens of millions. “It [the tunable laser] is a useful product that is selling but expectation didn’t match reality,” says Kozlov.

Another example is planar lightwave circuits used to make devices such as arrayed waveguide gratings used to multiplex and demultiplex wavelengths. “Intel was the biggest cheerleader,” says Kozlov. “Did planar lightwave circuits change the industry? No, but it is a useful technology.”

Where significant progress has been made is in the reliability, compactness and cost reduction of optical components. High-end lasers with complex control electronics have been replaced by small, single-chip devices that have minimal associated circuitry, says Kozlov.

Pragmatism not euphoria

The biggest surprise for Kozlov has been how many companies have survived the extremely tough market conditions. “There were almost no sales in 2001 and the market didn’t recover till 2004,” he says. Companies latched on to niche markets outside telecom to get by while many of the start-ups survived on their funding before folding, merging or being acquired by larger players.

“The leading companies such as Finisar, Excelight (now merged with Eudyna to form Sumitomo Electric Device Innovations), Avago Technologies and Opnext were also leading companies 10 years ago,” said Kozlov, who adds Oclaro, created with the merger of Bookham and Avanex.

The market has experienced hiccups since 2004 such as the dip of 2008-2009. “The worse is definitely behind us,” says Kozlov. Many vendors have a good vision as to what to do and plan accordingly. He notes companies are maintaining resources to be well placed to respond to rapid increases in demand. And profitability is rising sharply after the belt-tightening of 2008-09. “Whoever gets in first makes the profit,” says Kozlov. “That is what happened in 1999, although that was an extreme.”

Transceiver vendors and gross margins

Another notable development of the last decade has been the advent of optical transceivers. In the late 1990s system vendors such as Alcatel, Fujitsu, Marconi, NEC and Nortel designed their own optical systems before divesting their optical component arms. Optical component companies exploited the opportunity by developing optical transceivers to sell to the systems vendors.

LightCounting forecasts that the global optical transceiver market will total $2.2 billion in 2010, yet Kozlov still has doubts about the optical transceiver vendors’ business model. “Optical transceiver vendors still have to prove they are profitable and viable, that they are a real layer in the food chain.”

Comparing the gross margin performance of the industry layers that make up the telecom industry, optical transceiver vendors are last (see chart at the top of the page). Gross margin is an efficiency measure as to how well a vendor turns what they manufacture into income. Companies such as Cisco Systems have impressive gross margins of 75%. “You have to own a market, to have something unique to maintain such a margin,” says Kozlov.

Cisco has a unique position and to a degree so do semiconductors players which have gross margins twice those of the transceiver vendors. Contract manufacturers, however, have even lower margins than the 25% achieved by the transceiver vendors, adds Kozlov, but they benefit from large manufacturing volumes.

The main challenge for transceiver vendors is differentiating their products. There is also fierce competition across product segments. “A gross margin of 25% is not the end of the world as long as there are sufficient volumes,” says Kozlov. “And of course 25% in China is a lot – local [optical transceiver] vendors don’t think twice about entering the market.”

Kozlov says there are now between 20-30 Chinese optical transceiver vendors. “Some two thirds are benefiting from government funding but a third are building laser manufacturing and making transceivers, are real, and are here to stay.”

Bandwidth drives components

LightCounting collects quarterly shipment data from leading optical transceiver vendors worldwide. It also forecasts market demand based on a traffic model. Kozlov stresses the importance of the adoption of broadband schemes such as fibre-to-the-x (FTTx) as a traffic driver and ultimately transceiver sales.

A small change in the bandwidth utilisation of the access network has a huge impact on the network core. The advent of a killer application or the emergence of devices such as the iPhone and iPad that change user habits and drive access network utilisation from 2% to 5% would have a marked impact on operators’ networks. “This would require a significant upgrade and would result in a very nice bubble,” says Kozlov.

Utilised bandwidth (terabits-per-second). Scenario 2 with the higher utilisation in the access network quickly impacts core network capacity. Source: LightCounting

Utilised bandwidth (terabits-per-second). Scenario 2 with the higher utilisation in the access network quickly impacts core network capacity. Source: LightCounting

Another effect LightCounting has noted is that the total transceiver capacity is not keeping pace with growth in network traffic. This discrepancy is caused by operators running their networks more efficiently, explains Kozlov. Collapsing the number of platforms when operators adopt newer, more integrated systems is removing interfaces from the network.

LightCounting does not see operators’ traffic data such that Kozlov can’t know to what degrees operators are running their networks closer to capacity but given the rapid clip in traffic growth this is not a sustainable policy and hence does not explain this overall trend.

The next decade

Kozlov expects the next decade to continue like recent years with optical component companies being conservative and pragmatic. He is optimistic about optics’ adoption in the data centre as interface speeds move to 10Gbps and above, pushing copper to its limit. He also believes active optical cables are here to stay, while photonic integration will play an increasingly important role over time.

Kozlov also believes another bubble could occur especially if there is a need for more bandwidth at the network edge that will with a knock-on effect on the core.

But what gives him most optimism is that he simply doesn’t know. “We were all really wrong 10 years ago, maybe we will be again.”

- Lightwave July 2010: Interview with Vladimir Kozlov. "Can the optical transceiver industry sustain double-digit growth?

ROADMs: reconfigurable but still not agile

Part 2: Wavelength provisioning and network restoration

How are operators using reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexers (ROADMs) in their networks? And just how often are their networks reconfigured? gazettabyte spoke to AT&T and Verizon Business.

Operators rarely make grand statements about new developments or talk in terms that could be mistaken for hyperbole.

“You create new paths; the network is never finished”

“You create new paths; the network is never finished”

Glenn Wellbrock, Verizon Business

AT&T’s Jim King certainly does not. When questioned about the impact of new technologies, his answers are thoughtful and measured. Yet when it comes to developments at the photonic layer, and in particular next-generation reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexers (ROADMs), his tone is unmistakable.

“We really are at the cusp of dramatic changes in the way transport is built and architected,” says King, executive director of new technology product development and engineering at AT&T Labs.

ROADMs are now deployed widely in operators’ networks.

AT&T’s ultra-long-haul network is all ROADM-based as are the operator’s various regional networks that bring traffic to its backbone network.

Verizon Business has over 2,000 ROADMs in its medium-haul metropolitan networks. “Everywhere we deploy FiOS [Verizon’s optical access broadband service] we put a ROADM node,” says Glenn Wellbrock, director of backbone network design at Verizon Business.

“FiOS requires a lot of bandwidth to a lot of central offices,” says Wellbrock. Whereas before, one or two OC-48 links may have been sufficient, now several 10 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) links are needed, for redundancy and to meet broadcast video and video-on-demand requirements.

According to Infonetics Research, the optical networking equipment market has been growing at an annual compound rate of 8% since 2002 while ROADMs have grown at 46% annually between 2005 and 2009. Ovum, meanwhile, forecasts that the global ROADM market will reach US$7 billion in 2014.

While lacking a rigid definition, a ROADM refers to a telecom rack comprising optical switching blocks—wavelength-selective switches (WSSs) that connect lightpaths to fibres —optical amplifiers, optical channel monitors and control plane and management software. Some vendors also include optical transponders.

ROADMs benefit the operators’ networks by allowing wavelengths to remain in the optical domain, passing through intermediate locations without requiring the use of transponders and hence costly optical-electrical conversions. ROADMs also replace the previous arrangement of fixed optical add-drop multiplexers (OADMs), external optical patch panels and cabling.

Wellbrock estimates that with FiOS, ROADMs have halved costs. “Beforehand we used OADMs and SONET boxes,” he says. “Using ROADMs you can bypass any intermediate node; there is no SONET box and you save on back-to-back transponders.”

Verizon has deployed ROADMs from Tellabs, with its 7100 optical transport series, and Fujitsu with its 9500 packet optical networking platform. The first generation Verizon platform ROADMs are degree-4 with 100GHz dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) channel spacings while the second generation platforms have degree-8 and 50GHz spacings. The degree of a WSS-enabled ROADM refers to the number of directions an optical lightpath can be routed.

Network adaptation

Wavelength provisioning and network restoration are the main two events requiring changes at the photonic layer.

Provisioning is used to deliver new bandwidth to a site or to accommodate changes in the network due to changing traffic patterns. Operators try and forecast demand in advance but inevitably lightpaths need to be moved to achieve more efficient network routing. “You create new paths; the network is never finished,” says Wellbrock.

“We want to move around those wavelengths just like we move around channels or customer VPN circuits in today’s world”

Jim King, AT&T Labs

In contrast, network restoration is all about resuming services after a transport fault occurs such as a site going offline after a fibre cut. Restoration differs from network protection that involves much faster service restoration – under 50 milliseconds – and is handled at the electrical layer.

If the fault can be fixed within a few hours and the operator’s service level agreement with a customer will not be breached, engineers are sent to fix the problem. If the fault is at a remote site and fixing it will take days, a restoration event is initiated to reroute the wavelength at the physical layer. But this is a highly manual process. A new wavelength and new direction need to be programmed and engineers are required at both route ends. As a result, established lightpaths are change infrequently, says Wellbrock.

At first sight this appears perplexing given the ‘R’ in ROADMs. Operators have also switched to using tunable transponders, another core component needed for dynamic optical networking.

But the issue is that when plugged into a ROADM, tunability is lost because the ROADM’s restricts the operating wavelength. The lightpath's direction is also fixed. “If you take a tunable transponder that can go anywhere and plug it into Port 2 facing west, say, that is the only place it can go at that [network] ingress point,” says Wellbrock.

When the wavelength passes through intermediate ROADM stages – and in the metro, for example, 10 to 20 ROADM stages can be encountered - the lightpath’s direction can at least be switched but the wavelength remains fixed. “At the intermediate points there is more flexibility, you can come in on the east and send it out west but you can’t change the wavelength; at the access point you can’t change either,” says Wellbrock.

“Should you not be able to move a wavelength deployed on one route onto another more efficiently? Heck, yes,” says King. “We want to move around those wavelengths just like we move around channels or customer VPN circuits in today’s world.”

Moving to a dynamic photonic layer is also a prerequisite for more advanced customer services. “If you want to do cloud computing but the infrastructure is [made up of] fixed ‘hard-wired’ connections, that is basically incompatible,” says King. “The Layer 1 cloud should be flexible and dynamic in order to enable a much richer set of customer applications.”]

To this aim operators are looking to next-generation WSS technology that will enable ROADMS to change a signal’s direction and wavelength. Known as colourless and directionless, these ROADMs will help enable automatic wavelength provisioning and automatic network restoration, circumventing manual servicing. To exploit such ROADMs, advances in control plane technology will be needed (to be discussed in Part 3) but the resulting capabilities will be significant.

“The ability to deploy an all-ROADM mesh network and remotely control it, to build what we need as we need it, and reconfigure it when needed, is a tremendously powerful vision,” says King.

When?

Verizon’s Wellbrock expects such next-generation ROADMs to be available by 2012. “That is when we will see next-generation long-haul systems,” he says, adding that the technology is available now but it is still to be integrated.

King is less willing to commit to a date and is cautious about some of the vendors’ claims. “People tell me 100Gbps is ready today,” he quipped.

Other sections of this briefing

Part 1: Still some way to go

Part 3: To efficiency and beyond

Still some way to go

Part 1: The vision .... back in 2000

I came across this article (below) on the intelligent all-optical network. I wrote it in 2000 while working at the EMAP magazine, Communications Week International, later to become Total Telecom.

What is striking is just how much of the vision of a dynamic photonic layer is still to be realised. Back then it had also been discussed for over a decade. And bandwidth management, like in 2000, is still largely at the electrical layer.

And yet much progress has been made in networking technology. But the way the network has evolved means that a more flexible photonic layer, while wanted by operators, is only one aspect of the network optimisation they seek to reduce the cost of transporting bits.

The second and third parts of the dynamic optical networking briefing will discuss how often operators reconfigure their networks and what is required, as well as developments in reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexer (ROADM) and control plane technologies that promise to increase the flexibility of the photonic layer.

--+++--

Seeing the light (April 17th, 2000)

The next generation of networks is coming, with abundant bandwidth and flexible services available on-demand, and intelligent management and provisioning at the optical layer. Roy Rubenstein finds out what's in store and who's set fair in this optical future.

For all its air of novelty, all-optical networking is actually a mature idea. Discussed for the best part of a decade, all-optical networks have perennially promised to deliver the next generation of “intelligent” services, yet besides the stir caused by the arrival of dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM), forcing greater capacity over fiber networks, there has been little in the way of tangible development.

Now, with limited ceremony, optical networking is reasserting itself, and the signs are that you could reap the benefits sooner than you think.

What excites operators most is the prospect of bandwidth on demand: high-speed links set up with little more than a few mouse clicks. But the technology is creating dilemmas as well as opportunities. On the one hand, the newer operators can enter the market with a sleeker network - fewer layers and fewer nodes - accompanied by the latest billing and management software. On the other hand, incumbent operators are facing the dilemma of when to embrace the technology and how to integrate it with their legacy equipment.

“Most of the network planners agree this is the way to go,” says Barry Flanigan, senior consultant at Ovum Ltd., of London. "The question is the precise technology and timing."

Flexible bandwidth

Flexible bandwidth provisioning will enable a range of services that have not been practicable until now. For example, network planners in corporations will no longer have to guess - and live with the consequences - each time they budget their capacity requirements and agree horribly rigid contract terms.

In fact all manner of on-tap services become possible when bandwidth is set up and collapsed on an hourly or minute-by-minute basis. One example is bandwidth trading between carriers, enabling operators with their own networks to grab business such as voice services while demand is there, and off load capacity when it is not.

A further example is the broadcasting of sporting events. Instead of satellite coverage, a TV company could set up a cheaper terrestrial network link to each sporting venue, but provision capacity only for the duration of the event. And content providers can offer services locally. Opening pipes, a provider can download and store video on demand on a country-by-country basis ready for delivery, before closing the links.

“That way the service seems a lot quicker,” says Andy Wood, chief technology officer at Storm Telecommunications Ltd., based in London.

Adding intelligence

The key to this flexible bandwidth provisioning is optical switches, which introduce “intelligence” to the optical layer. An optical switch-whether electrically based or all-optical-routes complete wavelengths of light packed with up to 10 megabits of data.

“The scenario today is that bandwidth management is at the electrical layer,” says Richard Dade, director for industry liaison, optical networking group, at Lucent Technologies Inc., Murray Hill, New Jersey. “By the end of this year-2001 it will transition into the optical layer.”

This is also the view of Nick Critchell, product marketing manager for core optical internetworking products at San Jose, California-based Cisco Systems Inc. “Looking forward two years to the core routing, it will provide intelligent switching and intelligent restoration,” he says.

But others question the impact such technologies are having on the awareness of the underlying optical network. “Intelligence may be too strong a word for it,” says Dr. David Huber, chief executive of Corvis Corp., the Columbia, Maryland-based optical networking technology start-up.

What interests him is the sheer data traffic-handling capabilities--transporting terabits of data--and network efficiencies that all-optical switches promise. For example Huber predicts network utilization will exceed 80% using all optical switches. Current network utilization figures are below 50%.

When it comes to the operators, it seems the newer breed is keenest to embrace the technology. For them, adopting intelligent optical switching provides a simpler network, removing the need for Sonet/Synchronous Digital Hierarchy (SDH) transmission equipment. They also gain in reduced operating costs and system efficiencies through the use of the latest network operating system, billing and management systems.