Is the tunable laser market set for an upturn?

Part 2: Tunable laser market

"The tunable laser market requires a lot of patience to research." So claims Vladimir Kozlov, CEO of LightCounting Market Research. Kozlov should know; he has spent the last 15 years tracking and forecasting lasers and optical modules for the telecom and datacom markets.

Source: LightCounting, Gazettabyte

Source: LightCounting, Gazettabyte

The tunable laser market is certainly sizeable; over half a million units will be shipped in 2014, says LightCounting. But the market requires care when forecasting. One subtlety is that certain optical component companies - Finisar, JDSU and Oclaro - are vertically integrated and use their own tunable lasers within the optical modules they sell. LightCounting counts these as module sales rather than tunable laser ones.

Another issue is that despite the development of advanced reconfigurable optical add/ drop multiplexers (ROADMs) and tunable lasers, the uptake of agile optical networking has been limited.

"Verizon is bullish on getting the next generation of colourless, directionless and contentionless ROADMS to reconfigure the network on-the-fly," says Kozlov. "But I'm not so sure Verizon is going to be successful in convincing the industry that this is going to be a good market for [ROADM] suppliers to sell into."

Reconfigurability helps engineers at installations when determining which channels to add or drop, but there is little evidence of operators besides Verizon talking about using ROADMS to change bandwidth dynamically, first in one direction and then the other, he says.

Another indicator of the reduced status of tunable lasers is NeoPhotonics's intention to purchase Emcore's tunable external cavity laser as well as its module assets for US $17.5 million. Emcore acquired the laser when it bought Intel's optical platform division for $85 million in 2007, while Intel acquired it from New Focus in 2002 for $50 million. NeoPhotonics has also spent more in the past: it bought Santur's tunable laser for $39 million in 2011.

"There was so much excitement with so many players [during the optical bubble of 1999-2000], the market was way too competitive and eventually it drove vendors to the point where they would prefer to sell the business for pennies rather than keep it running," says Kozlov. "Emcore has been losing money, it is not a highly profitable business." Yet for Kozlov, Emcore's tunable laser is probably the best in the business with its very narrow line-width compared to other devices.

Tunable laser market

Tunable lasers have failed to get into the mainstream of the industry. "If you look at DWDM, I'm guessing that 70 percent of lasers sold are still fixed wavelength or temperature-tunable over a few wavelengths," says Kozlov. System vendors such as Huawei and ZTE advertise their systems with tunable lasers. "But when we asked them how they are using tunable lasers, they admitted that the bulk of their shipments are fixed-wavelength devices because whatever little they can save on cost, they will."

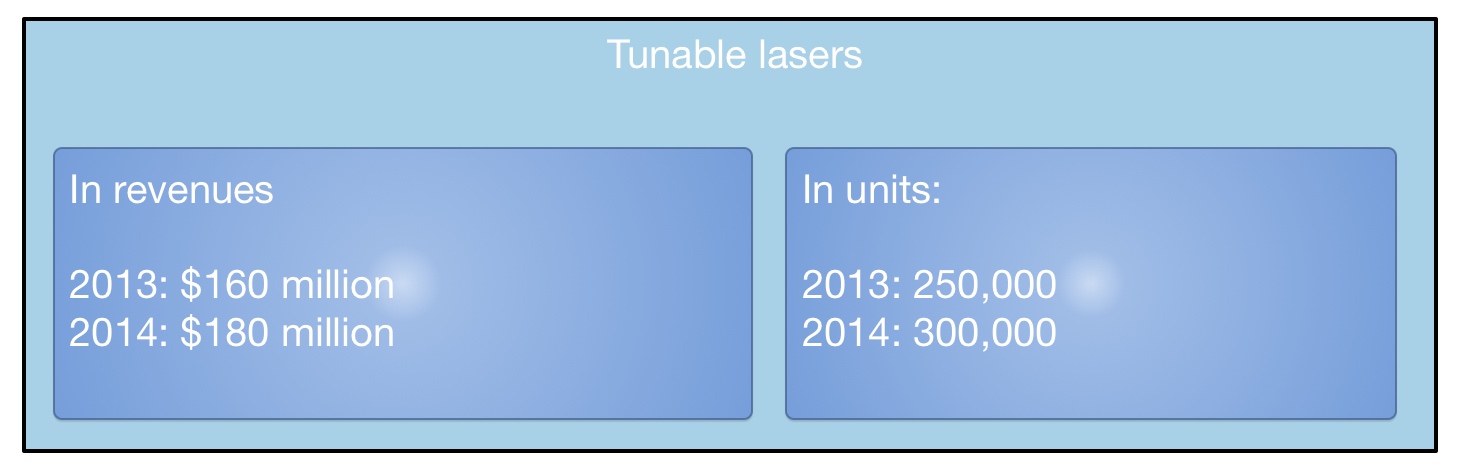

LightCounting valued the 2013 tunable laser market at $160 Million, growing to $180 Million in 2014. This equates to 250,000 units sold in 2013 and 300,000 units this year. "Most of these are for coherent systems," says Kozlov. The number of tunable lasers sold in modules - mainly XFPs but also SFPs and 300-pin modules - is 250,000 million units. "Half a million units a year; if you look at actual shipments, it is quite a lot," says Kozlov.

What next?

"I'm hoping we are reaching the low point in the tunable laser market as vendors are struggling and sales are at a very low valuation," says Kozlov.

The advent of more complex modulation schemes for 400 Gigabit and greater speed optical transmission, and the adoption of silicon photonics-based modulators for long haul will require higher powered lasers. But so much progress has been made by laser designers over the last 15 years, especially during the bubble, that it will last the industry for at least another decade or two, says Kozlov: "Incremental progress will continue and hopefully greater profitability."

For Part 1: NeoPhotonics to expand its tunable laser portfolio, click here

NeoPhotonics secures PIC specialist Santur

NeoPhotonics has completed the acquisition of Santur, the tunable laser and photonic integration specialist, boosting the company's annual turnover to a quarter of a billion dollars.

Source: Gazettabyte

Source: Gazettabyte

The acquisition helps NeoPhotonics become a stronger, vertically integrated transponder supplier. In particular, it broadens NeoPhotonics’ 40 and 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) component portfolio, turns the company into a leading provider of tunable lasers and enhances its photonic integration expertise.

“Our business over a number of years has grown as the importance of photonic integrated circuits and the products deriving from them have grown,” says Tim Jenks, CEO of NeoPhotonics. “We believe it is a critical part of the network architecture today and going forward.”

Some US $39.2M in cash has been paid for Santur, and could be up to $7.5M more depending on Santur’s products' market performance over the next year.

NeoPhotonics has largely focussed on telecom but Jenks admits it is broadening its offerings. “Certainly a very significant portion of fibre-optic components are consumed in data and storage, and while historically that has not been a significant part of NeoPhotonics, it is a large and important market overall,” says Jenks.

"It [optical components] portends the future of the technology industry"

Tim Jenks, NeoPhotonics

The company will continue to address telecom but will add products to additional segments, including datacom. In July, the company announced its first CFP module supporting the 40 Gigabit Ethernet (GbE) 40GBASE-LR4 standard. Santur also supplies 40Gbps and 100Gbps 10km transceivers, in QSFP and CFP form factors, respectively.

Santur made its name as a tunable laser supplier and is estimated to have a 50% market share, according to Ovum. More recently it has developed arrays of 10Gbps transmitters. Such photonic integrated circuits (PICs) are used for the 10x10 multi-source agreement (MSA).

The acquisition complements NeoPhotonics’ 40Gbps and 100Gbps integrated indium-phosphide receiver components, enabling the company to provide the various optical components needed for 40 and 100Gbps modules. Santur also has narrow line-width tunable laser technology used at the coherent transmitter and receiver. But Jenks confirms that the company has not announced a transmitter at 28Gbps using this narrow line-width laser.

10x10 MSA

Santur has been a key player in the 10x10 MSA, developed as a low cost competitor to the IEEE 100 Gigabit Ethernet (GbE) 10km 100GBASE-LR4 and 40km -ER4 standards.

Large content service providers such as Google want cheaper 100GbE interfaces and the 10x10 MSA module, built using 10x10Gbps electrical and optical interfaces, is approximately half the cost of the IEEE interfaces.

"There is an opportunity with the 10x10 MSA," says Jenks. "The 10x10 does not require the gearbox IC, it is therefore lower cost and lower power, and fulfills a need that a 4x25Gig, with a rather immature technology and a requirement for a gearbox IC, does not."

In August the 10x10 MSA announced further specifications: a 10km version of the 10x10 MSA as well as two 40km-reach WDM interfaces: a 4x10x10Gbps and an 8x10x10Gbps. "There are end users that want to use these," says Jenks.

“The ability for a system vendor to lead is a challenging task. For a system vendor to lead and simultaneous lead in developing their componentry is a daunting task.”

Acquisitions

NeoPhotonics has made several acquisitions over the years, including four in 2006 (see chart). But Santur's revenues - some $50m - are larger than the aggregated revenues of all the previous acquisitions.

"I think of acquisitions as being inorganic for maybe two years and after that they are all organic," says Jenks. The acquisitions have helped NeoPhotonics broaden its technologies, strengthen the company's know-how and acquire customers and relationships.

“If someone says what did you do with this product from that company, they are asking the wrong question,” says Jenks. “By the law of averages, some [acquisitions] do better, some do worse but overall it has been quite successful.”

System vendors and vertical integration

Jenks says he is aware of system vendors taking steps to develop components and technology in-house but he does not believe this will change the primary role of the component vendors.

"Equipment vendors are building some things in-house for a near-term cost advantage, better insights into cost of production or better insights in how the technology can go,” says Jenks. “All reasons to have some form of vertical integration.”

But in technology leadership, no one company has a monopoly of talent. As such vertical integration is a double-edged sword, he says, a company can become quite expert but it can also isolate itself from what the rest of the world is doing.

“The ability for a system vendor to lead is a challenging task,” says Jenks. “For a system vendor to lead, and simultaneous lead in developing their componentry, is a daunting task.”

The world is flat

Jenks, whose background is in mechanical and nuclear engineering, highlights two aspects that strike him about the optical component industry.

One is that telecoms is ubiquitous and because optical components go into telecoms, optical components is a global industry. "The world is very flat in optical components,” he says.

Second, the hurdles to undertake experiments in optical components is lower than the significant capital investment needed for nuclear engineering, for example. "Colleges and universities turn out graduates in physics and electrical engineering that are well trained and need a lighter physical plant,” says Jenks. This aspect of the education promotes a globally diverse and a rather 'flat' industry.

“When I go to a trade show in China, Europe or the US, I'm running into colleagues from the industry that I know from each country we do business, and that is a lot of countries,” he says.

All this, for Jenks, makes optical components a fascinating industry, one that is on the leading edge of technology and also industrial trend.

"It [optical components] portends the future of the technology industry: flatter and flatter with more global players and more global competition," says Jenks. “At the moment it is novel in optical components but in a few years' time it won't be unique to optical components.”

NeoPhotonics at a glance

The company segments its revenues into the areas of speed and agility (10-100Gbps products, planar lightwave circuits - ROADMs, arrayed waveguide gratings), access (FTTh, cable TV, wireless backhaul) and SDH and slow-speed DWDM, products designed 3-5 years ago.

Historically these three segments' revenues have been equal but this year the access business has been larger, accounting for 40% of revenues due to China's huge FTTx rollout.

Huawei is NeoPhotonics' largest customer. “They have been as much as half our revenue," says Jenks. And depending on the quarter, Ciena and Alcatel-Lucent have been reported as 10% customers.

Packet optical transport: Hollowing the network core

The platform enables a fully-meshed metropolitan network Intune Networks' CEO, Tim Fritzley (right) and John Dunne, co-founder and CTO with software support for web-based services, claims the Irish start-up.

Intune Networks' CEO, Tim Fritzley (right) and John Dunne, co-founder and CTO with software support for web-based services, claims the Irish start-up.

“What we have designed allows for the sharing of the same fibre switching assets across multiple services in the metro,” says Tim Fritzley, Intune’s CEO.

The company is in talks with several operators about its OPST system, which is being used for a nationwide network in Ireland. The system is also part of an EC seventh framework project that includes Spanish operator Telefónica.

OPST architecture

Intune’s OPST system, dubbed the Verisma iVX8000, uses dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) technology but with a twist. Each wavelength is assigned to a particular destination port, over which the data is transmitted in bursts. The result is an architecture that uses both wavelength-division and time-division multiplexing.

To enable the approach, Intune has developed a control algorithm that can switch and lock a tunable laser’s wavelength “in nanoseconds”. Such rapid laser switching enables wavelength addressing - assigning a dedicated wavelength to each destination port.

As packets arrive at the iVX8000, they are ‘coloured’ and queued before being sent on the required wavelength to their destination. In effect packets are routed at the optical layer, in contrast to traditional systems where traffic is packed onto a lightpath that has a fixed predefined point-to-point optical path.

The packets are sent in bursts based on their class-of-service. Intune uses a proprietary framing scheme for transmission, with Ethernet frames restored at the destination. At the input port, all the packets are queued based on their wavelength and class-of-service. The scheduler, which composes the bursts, picks bits to transmit from the queues based on their class, with the bits sent without having to be aligned with a frame’s boundaries.

“Instead of assigning an electrical address to a fixed wavelength, we are assigning electrical addresses to dynamic wavelengths”

“Instead of assigning an electrical address to a fixed wavelength, we are assigning electrical addresses to dynamic wavelengths”

Tim Fritzley, Intune Networks

Intune also uses dynamic bandwidth allocation: any bandwidth unused by the higher classes of service is assigned to lower priority traffic. This achieves over 80 percent utilisation of the Ethernet switching and the fibre, says Fritzley.

“You are responding to the dynamic loading of the traffic as it comes in, on a destination-by-destination, colour-by-colour basis,” says Fritzley “Instead of assigning an electrical address to a fixed wavelength [as with traditional systems], we are assigning electrical addresses to dynamic wavelengths.”

The result is a fully meshed architecture with any transponder able to talk to any other transponder on the network, says Fritzley.

System’s span

The network architecture is arranged as a ring with up to a 300km span. The ring connects up to 16 iVX8000 nodes each comprising four 10 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) ports and switching hardware. Each port is assigned a particular wavelength, equating to a total switch capacity of 640Gbps.

Intune has an 80-wavelength design even though only 64 are used. Indeed it uses two optical rings in parallel. The two rings run in opposite directions, providing optical protection for each port and effectively doubling overall capacity.

For the client side interfaces, the iVX8000 uses four 10 Gigabit Ethernet ports. Since transmissions are in bursts, multiple ports can transmit data to the same destination port even though they share the same wavelength.

The system’s 300km span is an artificial value set by Intune to guarantee “plug-and-play” performance. If the individual chassis are less than 65km apart and the total ring is 300km or under, Intune guarantees no DWDM engineering is required. “We auto-discover all the optical paths and nodes in the network; we automatically adjust all the amplification and set up the dispersion compensation,” says Fritzley. “This saves thousands of engineer-hours and truck rolls.”

Intune points out that it has engineered a 700km network but claims that for distances beyond 1,000km, point-to-point links connecting regions make more sense.

John Dunne, co-founder and CTO of Intune, claims the metro architecture simplifies networking greatly when connecting the network edge to the IP core. “It is different to what is there today because there are no routeing decisions to be made,” says Dunne. “All of the routes pre-exist, and that is because the tunable lasers contain all the colours of all the ports on the ring.”

As a result, setting up a flow of packets between the edge and core involves using a single interface to the ring. “You don’t have to talk to all the [ring’s] elements, you just talk to the ring,” says Dunne. “The ring is pre-engineered so it knows it’s a ring; it also knows how to guarantee the latency, the bandwidth, the jitter of any flow.”

This is the system’s main merit, says Dunne, the pre-engineered ring hides all the difficulty of building a control layer on top of a dynamic optical and layer-two switching system.

Bringing the web into the network

Intune realised that traditional telecom software would struggle to make best use of its distributed optical packet switch architecture. The company has adopted the representational state transfer (REST) software approach for its architecture instead.

“REST is the heart of web services,” says Fritzley. “The reason we did this is that there are hundreds of thousands of programmers that understand how to program it, so you are not into the arcane telecom languages of SNMP and TL1.” Adopting a 'RESTful' approach, claims Intune, reduces code development by 70 percent.

Moreover, REST by its nature is distributed such that it lends itself to supporting distributed transactions across Intune’s switch. “We have put a mini-http server on every card; we do not centralise control inside a node,” says Fritzley. “Every card peers with all of its peer-functions on the ring.”

In terms of the switch's operation, high-level XML commands are used instead of sending low-level instructions to numerous elements. “For example you ask the ring - set up this flow of packets with this bandwidth, this jitter and this delay,” says Dunne. “The ring replies that it can set this up and it performs the low-level stuff internal to the ring."

Such a capability will ultimately enable a machine to provision bandwidth for services, and enable machine-to-machine communications, says Intune. It will also enable third-party application developers to use the switch for service provisioning. This isn’t possible today because there is a lack of control, says Dunne.

“We have a full suite of XML-based interface commands,” he says. “All [the interface commands] would go to the carrier, the carrier would expose a subset to the Googles, the Googles would expose a subset to their application writers, and the application writers would expose a subset to the consumer.” Were the consumer to send a command to request some bandwidth, the call would be passed through the various layers directly into the switch, all in a controlled manner.

Provisioning of bandwidth in such an automated fashion is possible because Intune’s underlying network is bounded and predictable, says Dunne, with the optical path pre-engineered to work with the data path.

Meanwhile until XML becomes more commonplace, Intune uses a code translator that converts the XML code to SNMP or TL1 to interface to existing systems.

“The ring is pre-engineered so it knows it’s a ring; it also knows how to guarantee the latency, the bandwidth, the jitter of any flow”

“The ring is pre-engineered so it knows it’s a ring; it also knows how to guarantee the latency, the bandwidth, the jitter of any flow”

John Dunne, Intune Networks

Applications

The iVX8000 is being targetted at applications such as cloud computing services and the moving of virtualised environments between data centres. But the real target is using the platform to support multiple services – 3G and 4G wireless backhaul, on-demand IP TV as well as cloud. “No-one can do traffic planning anymore around such services,” says Fritzley.

The platform addresses what one large European operator calls ‘hollowing the core’. The operator wants to simplify its metro network by moving such networking elements as broadband remote access servers (BRASs) to the network edge. These will be connected using a simpler layer-two network that lessens the use of large, expensive IP core routers.”All the IP processing is on the edge and you go edge-to-edge on a flat layer two,” says Fritzley.

Market developments

Intune is using its system to enable the Exemplar network in Ireland. Backed by the Irish Government, the company’s systems will be used to build a nationwide network. The first phase involves a lab for application development and testing. So far 40 multi-nationals have signed up to use the network. Starting next year, a ring network will be up and running around Dublin to be followed with a nationwide roll-out in 2013.

The Irish start-up is also part of an EC Seventh Framework research project called MAINS. The project, which started in January, involves Telefónica which is using the iVX8000 to move virtualised resources between data centres depending on user demand and latency requirements. The project uses XML commands to call for bandwidth from the networking layer.

Meanwhile, Intune says that it is “deeply engaged” with four to five of the largest operators in North America and Europe.

Bringing WDM-PON to market

"We see just one way to bring down the cost, form-factor and energy consumption of the OLT’s multiple transceivers: high integration of transceiver arrays"

Klaus Grobe, ADVA Optical Networking

Considerable engineering effort will be needed to make next-generation optical access schemes using multiple wavelengths competitive with existing passive optical networks (PONs).

Such a multi-wavelength access scheme, known as a wavelength division multiplexing-passive optical network (WDM-PON), will need to embrace new architectures based on laser arrays and reflective optics, and use advanced photonic integration to meet the required size, power consumption and cost targets.

Current PON technology uses a single wavelength to deliver downstream traffic to end users. A separate wavelength is used for upstream data, with each user having an assigned time slot to transmit.

Gigabit PON (GPON) delivers 2.5 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) to between 32 or 64 users, while the next development, XG-PON, will extend GPON’s downstream data rate to 10 Gbps. The alternative PON scheme, Ethernet PON (EPON), already has a 10 Gbps variant. Vendors are also extending PON’s reach from 20km to 80km or more using signal amplification.

But the industry view is that after 10 Gigabit PON, the next step will be to introduce multiple wavelengths to extend the capacity beyond what a time-sharing approach can support. Extending the access network's reach to 100km will also be straightforward using WDM transport technology.

The advent of WDM-PON is also an opportunity for new entrants, traditional WDM optical transport vendors, to enter the access market. ADVA Optical Networking is one firm that has been vocal about its plans to develop next-generation access systems.

“We are seriously investigating and developing a next-generation access system and it is very likely that it will be a flavour of WDM-PON,” says Klaus Grobe, senior principal engineer at ADVA Optical Networking. “It [next-generation access] must be based on WDM simply because of bandwidth requirements.”

The system vendor views WDM-PON as addressing three main applications: wireless backhaul, enterprise connectivity and residential broadband. But despite WDM-PON’s potential to reduce operating costs significantly, the challenge facing vendors is reducing the cost of WDM-PON hardware. Indeed it is the expense of WDM-PON systems that so far has assigned the technology to specialist applications only.

A non-reflective tunable laser-based WDM-PON ONU. Source: ADVA Optical NetworkingAccording to Grobe, cost reduction is needed at both ends of the WDM-PON: the client receiver equipment known as the optical networking unit (ONU) and the optical line terminal (OLT) housed within an operator’s central office.

A non-reflective tunable laser-based WDM-PON ONU. Source: ADVA Optical NetworkingAccording to Grobe, cost reduction is needed at both ends of the WDM-PON: the client receiver equipment known as the optical networking unit (ONU) and the optical line terminal (OLT) housed within an operator’s central office.

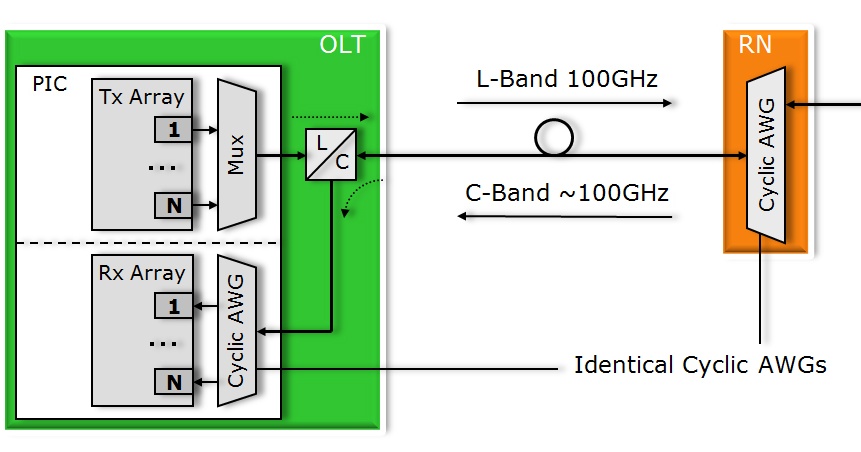

ADVA Optical Networking plans to use low-cost tunable lasers rather than a broadband light source and reflective optics for the ONU transceivers. “For the OLT, we see just one way to bring down the cost, form-factor and energy consumption of the OLT’s multiple transceivers: high integration of transceiver arrays,” says Grobe.

This is a considerable photonic integration challenge: a 40- or 80-wavelength WDM-PON uses 40 or 80 transceiver bi-directional clients, equating to 80 and 160 wavelengths. If 80 SFPs optical modules were used at the OLT, the resulting cost, size and power consumption would be prohibitive, says Grobe.

ADVA Optical Networking is working with several firms, one being CIP Technologies, to develop integrated transceiver arrays. ADVA Optical Networking and CIP Technologies are part of the EU-funded project, C-3PO, that includes the development of integrated transceiver arrays for WDM-PON.

Splitters versus filters

One issue with WDM-PON is that there is no industry-accepted definition. ADVA Optical Networking views WDM-PON as an architecture based on optical filters rather than splitters. Two consequences result once that choice is made, says Grobe.

One is insertion loss. Choosing filters implies arrayed waveguide gratings (AWGs), says Grobe. “No other filter technology is seriously considered for WDM-PON if filters are used,” he says.

With an AWG, the insertion loss is independent of the number of wavelengths supported. This differs from using a splitter-based architecture where every 1x2 device introduces a 3dB loss - “closer to 3.5dB”, he says. Using a 1x64 splitter, the insertion loss is 14 or 15dB whereas for a 40-channel AWG the loss can be as low as 4dB. “I just saw specs of a first 96-channel AWG, even that one isn’t much higher [than 4dB],” says Grobe. Thus using filters rather than splitters, the insertion loss is much lower for a comparable number of client ONUs.

There is also a cost benefit associated with a low insertion loss. To limit the cost of next-generation PON, the transceiver design must be constrained to a 25dB power budget associated with existing PON transceivers. “This is necessary to keep these things cheap, possibly dirt cheap,” says Grobe.

The alternative, using XG-PON’s sophisticated 10 Gbps burst-mode transceiver with its associated 35dB power budget, achieving low cost is simply not possible, he says. To live with transceivers with a 25dB power budget, the insertion loss of the passive distribution network must be minimised, explaining why filters are favoured.

The other main benefit of using filters is security. With a filter-based PON, wavelength point-to-point connections result. “You are not doing broadcast,” says Grobe. “You immediately get rid of almost all security aspects.” This is an issue with PON where traffic is shared.

Low power

Achieving a low-power WDM-PON system is another key design consideration. “In next-gen access, it is absolutely vital,” says Grobe. “If the technology is deployed on a broad scale - that is millions of user lines – every single watt counts, otherwise you end up with differences in the approaches that go into the megawatts and even gigawatts.”

There is also a benchmarking issue, says Grobe: the WDM-PON OLT will be compared to XG-PON’s even if the two schemes differ. Since XG-PON uses time-division multiplexing, there will be only one transceiver at the OLT. But this is what a 40- or 80-channel WDM-PON OLT will be compared with, even if the comparison is apples to pears, says Grobe.

WDM-PON workings

There are two approaches to WDM-PON.

In a fully reflective architecture, the OLT array and the ONUs are seeded using multi-wavelength laser arrays; both ends use the lasers arrays in combination with reflective optics for optical transmission.

ADVA Optical Networking is interested in using a reflective approach at the OLT but for the ONU it will use tunable lasers due to technical advantages. For example, using the same wavelength for the incoming and modulated streams in a reflective approach, Rayleigh crosstalk is an issue when the ONUs are 100km from the OLT. In contrast, Rayleigh crosstalk at the OLT is avoided because the multi-wavelength laser array is located only a few metres from the reflective electro-absorption modulators (REAMs).

REAMs are used rather than semiconductor optical amplifiers (SOAs) to modulate data at the OLT because they support higher bandwidth 10 Gbps wavelengths. Indeed the C-3PO project is likely to use a monolithically integrated SOA-REAM for this task. “The reflective SOA is narrower in bandwidth but has inherent gain while the REAM has loss rather than gain – it is just a modulator,” says Grobe. “The combination of the two is the ideal: giving high modulation bandwidth and high transmit power.”

The integrated WDM-PON OLT. In practice the transmit array uses a reflective architecture based on SOA-REAMs and is fed with a multi-wavelength laser source. Source: ADVA Optical Networking

The integrated WDM-PON OLT. In practice the transmit array uses a reflective architecture based on SOA-REAMs and is fed with a multi-wavelength laser source. Source: ADVA Optical Networking

For the OLT, a multi-wavelength laser is fed via an AWG into an array of SOA-REAMs which modulate the wavelengths and return them through the AWG where they are multiplexed and transmitted to the ONUs via a demultiplexing AWG. An added benefit of this approach, says Grobe, is that the same multi-wavelength laser source can be use to feed several WDM-PON OLTs, further decreasing system cost.

For the upstream path, each ONU’s wavelength is separated by the OLT’s AWG and fed to the receiver array. In a WDM-PON system, the OLT transmit wavelengths and receive wavelengths (from the ONUs) operate in separate optical bands.

Grobe expects its resulting WDM-PON system to use 40 or 80 channels. And to best meet size, power and cost constraints, the OLT design will likely implemented as a photonic integrated circuit. “We are after a single PIC solution,” he says. “It is clear that with the OLT, integration is the only way to meet requirements.” A photonically-integrated OLT design is one of the products expected from the C-3PO project, using CIP Technologies' hybrid integration technology.

ADVA Optical Networking has already said that its WDM-PON OLT will be implemented using its FSP 3000 platform.

- To see some WDM-PON architecture slides, click here.

Oclaro: R&D key for growth

“We didn’t sell to Intel,” explains Alain Couder, the boss of Oclaro. “Intel looked for a fab[rication plant] that has good VCSEL technology and that could scale and they found us.”

Couder was talking about how Oclaro became a supplier of vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers (VCSELs) for Intel’s Light Peak optical cable interface technology. VCSELs are part of Oclaro’s Advanced Photonics Solutions, a division addressing non-telecom markets accounting for between 10 and 15 percent of the company’s revenues.

“I believe very clearly that if a component is available on the market, even if you are a module builder, you are much better off selling to your competition rather than having others do so.”

Alain Couder, Oclaro

Couder joined Bookham in August 2007 and oversaw its merger with Avanex in 2009, resulting in Oclaro. The restructuring has been intensive, with unprofitable product lines discontinued, facilities closed and jobs cut.

“During all this restructuring we never cut R&D,” says Couder. “We have been able to increase our [R&D] people as a third are now in Asia,” he says. “Even in Europe – the UK and Italy – [the cost of] engineers are two-thirds that of the US or Japan.” Indeed Couder says the company is increasing R&D spending from 11 to 13 percent of its revenues. “With growth that we have had - on average 10 percent quarter-on-quarter - we are hiring R&D staff as quickly as we can.”

Vertical integration

Oclaro’s CEO believes being a vertically integrated company – making optical components and modules – is an important differentiator. By designing optical components, Oclaro can drive down cost and tailor designs that it can sell to system vendors and module makers. Such a capability also benefits Oclaro’s own modules.

Couder stresses that there is no conflict of interest selling optical components to module firms that Oclaro competes with. “I believe very clearly that if a component is available on the market, even if you are a module builder, you are much better off selling to your competition rather than having others do so.”

Oclaro supplies components to the likes of Finisar and Opnext, he says, and it has not stopped Oclaro being successful with its 10 Gigabit small form factor (SFF) transponder. Being vertically integrated benefits Oclaro’s modules, growing its market share, says Couder: “Like this year with the SFF and as we expect to be doing next year with our tunable XFPs.” Selling 10 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) modules also means telecom vendors are buying more modules and less optical components.

“We are going to pursue the same strategy at 40 and 100 Gig,” says Couder. System vendors such as Alcatel-Lucent and Ciena may design their line side optics but as designs become cheaper and performance optimised, Oclaro will be better able to compete. “Our own module solution, or at least our gold box, becomes more competitive than their own design,” he says.

Another important technology aiding vertical integration is photonic integration. “As you put more functions on one chip you get better value,” says Couder. Oclaro has integrated a laser and modulator in indium phosphide that replaces two optical functions that until now have been sold separately. The integrated design takes a third less space yet Oclaro can sell it at a better margin.

40 and 100Gbps markets

Oclaro supplies optical components for 40Gbps differential phase-shift keying (DPSK) modulation and offers its own components and module for 40Gbps differential quadrature phase-shift keying (DQPSK) for the metro/ regional market. Indeed Oclaro is a DQPSK reference design provider for Huawei, the Chinese system vendor with more than 30 percent market share at 40Gbps.

Oclaro is also developing a 100Gbps coherent detection module based on polarisation multiplexing quadrature phase-shift keying (PM-QPSK) modulation, the industry defacto standard. “We think for the very long haul there might be a small market for PM-QPSK at 40Gbps but most of the coherent modulation will be at 100Gbps,” says Couder. “But at the [40Gbps] module level we are continue to be focused on DQPSK.”

Given the recent flurry of 100Gbps coherent announcements, is Oclaro seeing signs of 40Gbps being squeezed and becoming a stop-gap market? “

The only thing I can tell you is that I got this morning again an escalation from one top customer because we can’t supply optical components fast enough for their 40Gbps deployment,” says Couder. “This is all the noise around coherent - 100Gbps will be deployed but even at 100Gbps people are looking at shorter distance solution that are cheaper than coherent. I have not seen any slowing down of 40Gbps.”

He expects 40Gbps to mirror the 10Gbps market which is set for healthy sales over the coming two to three years. Prices continue to come down at 10Gbps and the same is happening at 40Gbps. Ten gigabit modules range from $1,500 to $1,800 depending on their specification while 40Gbps modules are around $6,000. Meanwhile 100Gbps modules will at least be twice the cost of 40Gbps. “There are many sub-networks deployed with [40Gbps] DPSK and DQPSK and I don’t see how operators are going to change everything to 100Gbps on those sub-networks,” says Couder.

Clariphy investment

Oclaro recently announced it had invested US $7.5 million in chip firm Clariphy Communications. Oclaro will develop with Clariphy coherent receiver chip technology for 100Gbps optical transmission and co-market Clariphy's ICs. “We will train our sales force on Clariphy products so we can present to our customers a combination of optical and high-speed components,” says Couder. “We will go as far as giving reference designs.”

In addition to the emerging 100Gbps, there will be marketing of Oclaro’s tunable XFP+ with Clariphy’s ICs and also co-marketing of 40Gbps technology, for example Oclaro’s balanced receiver working with Clariphy’s 40Gbps coherent IC.

Choosing Clariphy was straightforward, says Couder. There were only three “serious” component suppliers: CoreOptics, Opnext and Clariphy. Cisco Systems has announced its plan to acquire CoreOptics while Opnext is a competitor. But Couder stresses that the investment in Clariphy also follows two years of working together.

Couder agrees that the 100Gbps coherent application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) market is heating up and that there are many potential entrants. That said, he is unaware of many other players that can present a combination of optical components and the ASIC. He also thinks Clariphy has an elegant ASIC that combines the analogue and digital circuitry on one chip.

Meanwhile the Cisco acquisition of CoreOptics is good news for Oclaro. “It took one of the suppliers out of the market; one that was well positioned.” Oclaro is also a supplier of optical components to CoreOptics and to Cisco. “We expect to continue to supply and for us this will be a plus as it [Cisco/ CoreOptics’s solutions] will scale much faster,” he says.

Growth

In other product areas, Oclaro is focussing on its tunable XFP after first launching a extended XFP tunable laser design. “We’re sampling this quarter the regular tunable XFP,” says Couder. “We have been selling a few extended XFPs – the X2 – but the big market is the tunable XFP.”

Oclaro has two offerings – a replacement for the 80km fixed-wavelength XFP that will ship at the end of the end of the year, and a higher specification tunable XFP aimed at replacing 10Gbps 300-pin tunable modules. Couder admits JDS Uniphase dominates tunable XFPs having been first to market. “But we are coming very close behind and what customers are telling me is our performance is better.”

The market for optical amplifiers is also experiencing growth. “We are back to the level before the downturn, back to the level of September 2008,” he says.

The drivers? More optical networking links in the core are being deployed to accommodate growth in wireless traffic, video servers and FTTx, he says. Oclaro is also starting to see demand for lower latency networks. “Some financial applications are looking for lower latency,” he says. “They need gain blocks for 40Gig now and 100Gig tomorrow.” Another telecom segment Oclaro claims it is doing well is tunable optical dispersion compensation modules.

Outside telecom Oclaro's next generation pump products are finding use in cosmetic products while its VCSELs are being used for a future disk drive design. Then there is Light Peak, Intel’s high-speed optical cable technology to link electronic devices. “Intel’s Light Peak will be big; when exactly it will deployed I'm not in a position to say but it will be calendar year 2011.”