BT’s first quantum key distribution network

The trial of a commercial quantum-secured metro network has started in London.

The BT network enables customers to send data securely between sites by first sending encryption keys over optical fibre using a technique known as quantum key distribution (QKD).

The attraction of QKD is that any attempt to eavesdrop and intercept the keys being sent is discernable at the receiver.

The network uses QKD equipment and key management software from Toshiba while the trial also involves EY, the professional services company.

EY is using BT’s network to connect two of its London sites and will showcase the merits of QKD to its customers.

London’s quantum network

BT has been trialling QKD for data security for several years. It had announced a QKD trial in Bristol in the U.K. that uses a point-to-point system linking two businesses.

BT and Toshiba announced last October that they were expanding their QKD work to create a metro network. This is the London network that is now being trialled with customers.

Building a quantum-secure network is a different proposition from creating point-to-point links.

“You can’t build a network with millions of separate point-to-point links,” says Professor Andrew Lord, BT’s head of optical network research. “At some point, you have to do some network efficiency otherwise you just can’t afford to build it.”

BT says quantum security may start with bespoke point-to-point links required by early customers but to scale a secure quantum network, a common pipe is needed to carry all of the traffic for customers using the service. BT’s commercial quantum network, which it claims is a world-first, does just that.

“We’ve got nodes in London, three of them, and we will have quantum services coming into them from different directions,” says Lord.

Not only do the physical resources need to be shared but there are management issues regarding the keys. “How does the key management share out those resources to where they’re needed; potentially even dynamically?” says Lord.

He describes the London metro network as QKD nodes with links between them.

One node connects Canary Wharf, London‘s financial district. Another node is in the centre of London for mainstream businesses while the third node is in Slough to serve the data centre community.

“We’re looking at everything really,” says Lord. “But we’d love to engage the data centre side, the financial side – those two are really interesting to us.”

Customers’ requirements will also differ; one might want a quantum-protected Ethernet service while another may only want the network to provide them with keys.

“We have a kind of heterogeneous network that we’re starting to build here, where each customer is likely to be slightly different,” says Lord.

QKD and post-quantum algorithms

QKD uses physics principles to secure data but cryptographic techniques also being developed are based on clever maths to make data secure, even against powerful future quantum computers.

Such quantum-resistant public-key cryptographic techniques are being evaluated and standardised by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

BT says it plans to also use such quantum-resistant techniques and are part of its security roadmap.

“We need to look at both the NIST algorithms and the key QKD ones,” says Lord. “Both need to be developed and to be understood in a commercial environment.“

Lord points out that the encryption products that will come out of the NIST work are not yet available. BT also has plenty of fibre, he says, which can be used not just for data transmission but also for security.

He also points out that the maths-based techniques will likely become available as freeware. “You could, if you have the skills, implement them yourself completely freely,” says Lord. “So the guys that make crypto kits using these maths techniques, how do they make money?”

Also, can a user be sure that those protocols are secure? “How do you know that there isn’t a backdoor into those algorithms?” says Lord. “There’s always this niggling doubt.”

BT says the post-quantum techniques are valuable and their use does not preclude using QKD.

Satellite QKD

Satellites can also be used for QKD.

Indeed, BT has an agreement with UK start-up Arqit which is developing satellite QKD technology whereby BT has exclusive rights to distribute and market quantum keys in the UK and to UK multinationals.

BT says satellite and fibre will both play a role, the question is how much of each will be used.

“They work well together but the fibre is not going to go across oceans, it’s going to be very difficult to do that,” says Lord. “And satellite does that very well.”

However, satellite QKD will struggle to provide dense coverage.

“If you think of a low earth orbit satellite coming overhead, it’s only gonna be able to lock onto to one ground station at a time, and then it’s gone somewhere else around the world,” says Lord. More satellites can be added but that is expensive.

He expects that a small number of satellite-based ground stations will be used to pick up keys at strategic points. Regional key distribution will then be used, based on fibre, with a reach of up to 100km.

“You can see a way in which satellite the fibre solutions come together,” says Lord, the exact balance being determined by economics.

Hollow-core fibre

BT says hollow-core fibre is also attractive for QKD since the hollowness of the optical fibre’s core avoids unwanted interaction between data transmissions and the QKD.

With hollow-core, light carrying regular data doesn’t interact with the quantum light operating at a different wavelength whereas it does for standard fibre that has a solid glass core.

“The glass itself is a mechanism that gets any photons talking to each other and that’s not good,” says Lord. “Particularly, it causes Raman scattering, a nonlinear process in glass, where light, if it’s got enough power, creates a lot of different wavelengths.”

In experiments using standard fibre carrying classical and quantum data, BT has had to turn down the power of the data signal to avoid the Raman effect and ensure the quantum path works.

Classical data generate noise photons that get into the quantum channel and that can’t be avoided. Moreover, filtering doesn’t work because the photons can’t be distinguished. It means the resulting noise stops the QKD system from working.

In contrast, with hollow-core fibre, there is no Raman effect and the classical data signal’s power can be ramped to normal transmission levels.

Another often-cited benefit of hollow-core fibre is its low latency performance. But for QKD that is not an issue: the keys are distributed first and the encryption may happen seconds or even minutes later.

But hollow-core fibre doesn’t just offer low latency, it offers tightly-controlled latency. With standard fibre the latency ‘wiggles around’ a lot due to the temperature of the fibre and pressure. But with a hollow core, such jitter is 20x less and this can be exploited when sending photons.

“As time goes on with the building of quantum networks, timing is going to become increasingly important because you want to know when your photons are due to arrive,” says Lord.

If a photon is expected, the detector can be opened just before its arrival. Detectors are sensitive and the longer they are open, the more likely they are to take in unwanted light.

“Once they’ve taken something in that’s rubbish, you have to reset them and start again,” he says. “And you have to tidy it all up before you can get ready for the next one. This is how these things work.“

The longer that detector can be kept closed, the better it performs when it is opened. It also means a higher key rate becomes possible.

“Ultimately, you’re going to need much better synchronisation and much better predictability in the fibre,” says Lord. “That’s another reason why I like hollow-core fibre for QKD.”

Quantum networks

“People focussed on just trying to build a QKD service, miss the point; that’s not going to be enough in itself,” says Lord. “This is a much longer journey towards building quantum networks.”

BT sees building quantum small-scale QKD networks as the first step towards something much bigger. And it is not just BT. There is the Innovate UK programme in the UK. There are also key European, US and China initiatives.

“All of these big nation-states and continents are heading towards a kind of Stage I, building a QKD link or a QKD network but that will take them to bigger things such as building a quantum network where you are now distributing quantum things.”

This will also include connecting quantum computers.

Lord says different types of quantum computers are emerging and no one yet knows which one is going to win. He believes all will be employed for different kinds of use cases.

“In the future, there will be a broad range of geographically scattered quantum computing resources, as well as classical compute resources,” says Lord. “That is a future internet.”

To connect such quantum computers, quantum information will need to be exchanged between them.

Lord says BT is working with quantum computing experts in the UK to determine what the capabilities of quantum computers are and what they are good at solving. It is classifying quantum computing capabilities into the different categories and matching them with problems BT has.

“In some cases, there’s a good match, in some cases, there isn’t,” says Lord. “So we try to extrapolate from that to say, well, what would our customers want to do with these and it’s a work in progress.”

Lord says it is still early days concerning quantum computing. But he expects quantum resources to sit alongside classical computing with quantum computers being used as required.

“Customers probably won’t use it for very long; maybe buying a few seconds on a quantum computer might be enough for them to run the algorithm that they need,” he says. In effect, quantum computing will eventually be another accelerator alongside classical computing.

”You already can buy time by the second on things like D-Wave Systems’ quantum computers, and you may think, well, how is that useful?” says Lord. “But you can do an awful lot in that time on a quantum computer.”

Lord already spends a third of his working week on quantum.

“It’s such a big growing subject, we need to invest time in it,” says Lord.

A quantum leap in fear

The advent of quantum computing poses a threat which could break open the security systems protecting the world’s financial data and transactions.

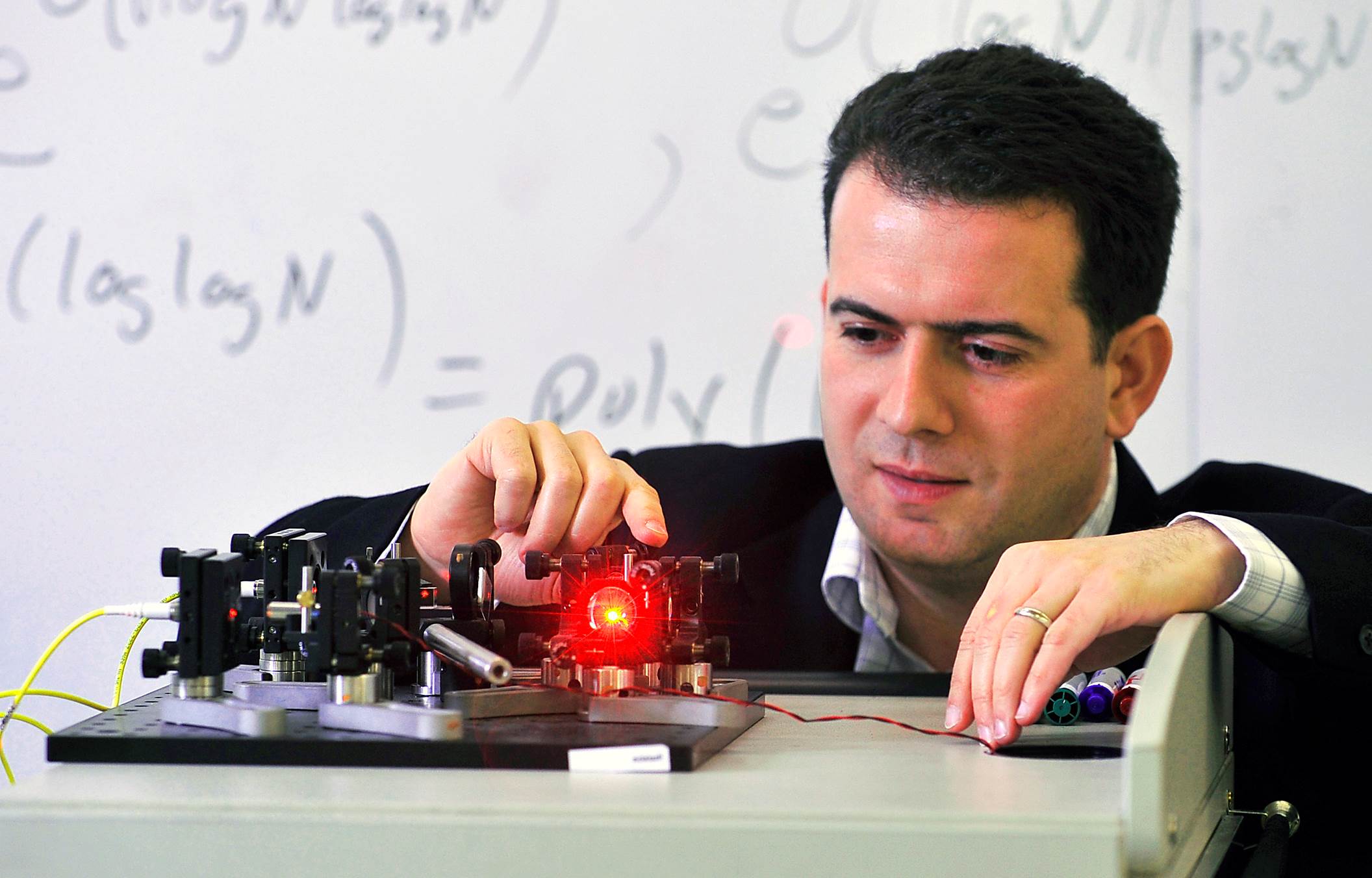

Professor Michele Mosca

Professor Michele Mosca

Protecting financial data has always been a cat-and-mouse game. What is different now is that the cat could be de-clawed. Quantum computing, a new form of computer processing, promises to break open the security systems that safeguard much of the world’s financial data and transactions.

Quantum computing is expected to be much more powerful than anything currently available because it does not rely on the binary digits 1 or 0 to represent data but exploits the fact that subatomic particles can exist in more than one state at once.

Experts cannot say with certainty when a fully-fledged quantum computer will exist but, once it does, public key encryption schemes in use today will be breakable. Quantum computer algorithms that can crack such schemes have already been put through their paces.

The good news is that cryptographic techniques resilient to quantum computers exist. And while such “quantum-safe” technologies still need to be constructed, security experts agree that financial institutions must prepare now for a quantum-computer world.

Experts cannot say with certainty when a fully-fledged quantum computer will exist but, once it does, public key encryption schemes in use today will be breakable

Ticking clock

There is a 50 percent chance that a quantum computer will exist by 2031, according to Professor Michele Mosca, co-founder of the Institute for Quantum Computing at the University of Waterloo, Canada, and of security company evolutionQ.

A one-in-two chance of a fully working quantum computer by 2031 suggests financial institutions have time to prepare, but that is not the case. Since financial companies are required to keep data confidential for many years, quantum-safe protocols need to be in place for the same length of time that confidentiality is mandated prior to quantum computing. So, for example, if data must be kept confidential for seven years, quantum-safe techniques need to be in place by 2024 at the latest. Otherwise, cyber criminals need only intercept and store RSA-encrypted data after 2024 and wait until 2031 to have a 50-50 chance of access to sensitive information.

Unsurprisingly, replacing public key infrastructure with quantum-safe technology is itself a multi-year project. First, the new systems must be tested and verified to ensure they meet existing requirements – not just that their implementation is secure but that their execution times for various applications are satisfactory. Then, all the public key infrastructure needs to be revamped – a considerable undertaking. This means that, if upgrading infrastructure takes five years, companies should be preparing if quantum computers arrive by 2031.

Professor Renato Renner, the head of the quantum information theory research group at ETH Zurich, the Swiss science and technology university, sees the potential for even more immediate risk. “Having a full-blown quantum computer is not necessarily what you need to break cryptosystems,” he says. In his view, financial companies should be worried that there are already early examples of quantum computers that are stronger than current computers. “It could well be that in five years we have already sufficiently powerful devices that can break RSA cryptosystems,” says Renner.

Quantum-safe approaches

Quantum-safe technologies comprise two approaches, one based on maths and another that exploits the laws of physics.

The maths approach delivers new public key algorithms that are designed to be invulnerable to quantum computing, known as post-quantum or quantum-resistant techniques.

The US National Institute of Science and Technology is taking submissions for post-quantum algorithms with the goal of standardising a suite of protocols by the early to mid-2020s. These include lattice-based, coding-based, isogenies-based and hash-function-based schemes. The maths behind these schemes is complex but the key is that none of them is based on the multiplication of prime numbers and hence susceptible to factoring, which is what quantum computers excel at.

It could well be that in five years we have already sufficiently powerful devices that can break RSA cryptosystems

Nigel Smart, co-founder of Dyadic Security, a software-defined cryptography company, points out that companies are already experimenting with post-quantum lattice schemes. Earlier this year, Google used it in experimental versions of its Chrome browser when talking to its sites. “My betting is that lattice-based systems will win,” says Smart.

The other quantum-safe approach exploits the physics of the very small – quantum mechanics – to secure links so that an eavesdropper on the link cannot steal data. Here particles of light – photons – are used to send the key used to encrypt data (see Cryptosystems – two ways to secure data below) where each photon carries a digital bit of the key.

Financial and other companies that secure data should already be assessing the vulnerabilities of their security systems

Should an adversary eavesdrop with a photodetector and steal the photon, the photon will not arrive at the other end. Should the hacker be more sophisticated and try to measure the photon before sending it on, here they come up against the laws of physics where measuring a photon changes its parameters.

Given these physical properties of photons, the sender and receiver typically reserve at random a number of the key’s photons to detect a potential eavesdropper. If the receiver detects an altered photon, the change suggests the link is compromised.

But quantum key distribution only solves a particular class of problem – for example, protecting data sent across links such as a bank sending information to a data centre for back-up. Moreover, the distances a single photon can travel is a few tens of kilometres. If longer links are needed, intermediate trusted sites are required to regenerate the key, which is expensive and cumbersome.

The technique is also dependent on light and so is not as widely applicable as quantum-resistant techniques. “People are more interested in post-quantum cryptography,” claims Smart.

What now?

BT, working with Toshiba and ADVA Optical Networking, the optical transport equipment maker, has demonstrated a quantum-protected link operating at 100 gigabits-per-second.

What is missing still is a little bit more industrialisation,” says Andrew Lord, head of optical communications at BT. “Quantum physics is pretty sound but we still need to check that the way this is implemented, there are no ways of breaching it.”

Kelly Richdale

Kelly Richdale

ID Quantique, the Swiss quantum-safe crypto technology company, supplied one early-adopter bank with its quantum key distribution system as far back as 2007. The bank uses a symmetric key scheme coupled with a quantum key.

“You can think of it as adding an additional layer of quantum security on top of everything you already have,” says Kelly Richdale, ID Quantique’s vice-president of quantum-safe security.

“Quantum key distribution has provable security. You know it will be safe against a quantum computer if implemented correctly,” she says. “With post-quantum algorithms, it is a race against time, since in the future there may be new quantum attacks that could render them as vulnerable as RSA.”

Andersen Cheng, chief executive of start-up PQ Solutions, a security company with products including secure communication using post-quantum technology, argues that both quantum- resistant and quantum key distribution will be needed. “You can use both but quantum key distribution on its own is not enough and it is expensive,” he says.

Most organisations do not have a detailed map of where all their information assets are and which business functions rely on which crypto algorithms

What next?

Mosca says that leading financial services companies are aware of the threat posed by quantum computing but their strategies vary: some point to more pressing priorities while others want to know what they can buy now to solve the problem.

He disagrees with both extreme approaches. Financial companies should, in his view, already be assessing the vulnerabilities of their systems. “Most organisations do not have a detailed map of where all their information assets are and which business functions rely on which crypto algorithms,” he says.

Companies should also plan for their systems to change a lot over the next decade. That is why it is premature to settle on a solution now since it will probably need upgrading. And they must test quantum-resistant algorithms. “We don’t have a winner yet,” says Mosca.

Most importantly, financial institutions cannot afford to delay. “Do you really want to be in the catch-up game and hope someone else will solve the problem for you?” asks Mosca.

The article first appeared in the June-July issue of the Financial World, the journal of The London Institute of Banking & Finance, published six times per year in association with the Centre for The Study of Financial Innovation (CSFI).

Cryptosystems – two ways to secure data

To secure data, special digital “keys” are used to scramble the information. Two encryption schemes are used – based on asymmetric and symmetric keys.

Public key cryptography that uses a public and private key pair is an example of an asymmetric scheme. The public key, as implied by the name, is published with the user’s name. Any party wanting to send data securely to the user employs the published public key to scramble the data. Only the recipient, with the associated private key, can decode the sent data. The RSA algorithm is a widely used example. (RSA stands for the initials of the developers: Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir and Leonard Adleman.) A benefit of public key cryptography is that it can be used as a digital signature scheme as well as for protecting data. The downside is that it requires a lot of processing power and is slow even then.

Symmetric schemes, in contrast, are much less demanding to run and use the same key at both link ends to lock and unlock the data. A well-known symmetric key algorithm is the Advanced Encryption Standard, which uses keys up to 256-bits long (AES-256); the more bits, the more secure the encryption.

The issue with the symmetrical scheme is getting the secret key to the recipient without it being compromised. One way is to send a security guard handcuffed to a locked case. A more digital-age approach is to send the secret key over a secure link. Here, public key cryptography can be used; the asymmetric key scheme can be employed to protect the symmetric key transmission prior to secure symmetric communication.

Quantum computing is a potent threat because it undermines both schemes when existing public key cryptography is involved.

BT bolsters research in quantum technologies

BT is increasing its investment in quantum technologies. “We have a whole team of people doing quantum and it is growing really fast,” says Andrew Lord, head of optical communications at BT.

The UK incumbent is working with companies such as Huawei, ADVA Optical Networking and ID Quantique on quantum cryptography, used for secure point-to-point communications. And in February, BT joined the Telecom Infra Project (TIP), and will work with Facebook and other TIP members at BT Labs in Adastral Park and at London’s Tech City. Quantum computing is one early project.

Andrew LordThe topics of quantum computing and data security are linked. The advent of quantum computers promises the break the encryption schemes securing data today, while developments in quantum cryptography coupled with advances in mathematics promise new schemes resilient to the quantum computer threat.

Andrew LordThe topics of quantum computing and data security are linked. The advent of quantum computers promises the break the encryption schemes securing data today, while developments in quantum cryptography coupled with advances in mathematics promise new schemes resilient to the quantum computer threat.

Securing data transmission

To create a secure link between locations, special digital keys are used to scramble data. Two common data encryption schemes are used, based on symmetric and asymmetric keys.

A common asymmetric key scheme is public key cryptography which uses a public and private key pair that are uniquely related. The public key is published along with its user’s name. Any party wanting to send data securely to the user looks up their public key and uses it to scramble the data. Only the user, which has the associated private key, can unscramble the data. A widely used public-key crypto-system is the RSA algorithm.

There are algorithms that can be run on quantum computers that can crack RSA. Public key crypto has a big question mark over it in the future and anything using public key crypto now also has a question mark over it.

In contrast, symmetric schemes use the same key at both link ends, to lock and unlock the data. A well-known symmetric key algorithm is the Advanced Encryption Standard which uses keys up to 256-bits long (AES-256); the more bits, the more secure the encryption.

The issue with a symmetrical key scheme, however, is getting the key to the recipient without it being compromised. One way is to deliver the secret key using a security guard handcuffed to a case. An approach more befitting the digital age is to send the secret key over a secure link, and here, public key cryptography can be used. In effect, an asymmetric key is used to encrypt the symmetric key for transmission to the destination prior to secure communication.

But what worries governments, enterprises and the financial community is the advent of quantum computing and the risk it poses to cracking public key algorithms which are the predominant way data is secured. Quantum computers are not yet available but government agencies and companies such as Intel, Microsoft and Google are investing in their development and are making progress.

Michele Mosca estimates that there is a 50 percent chance that a quantum computer will exist by 2030. Professor Mosca, co-founder of the Institute for Quantum Computing at the University of Waterloo, Canada and of the security firm, evolutionQ, has a background in cyber security and has researched quantum computing for 20 years.

This is a big deal, says BT’s Lord. “There are algorithms that can be run on quantum computers that can crack RSA,” he says. “Public key crypto has a big question mark over it in the future and anything using public key crypto now also has a question mark over it.”

A one-in-two chance by 2030 suggests companies have time to prepare but that is not the case. Companies need to keep data confidential for a number of years. This means that they need to protect data to the threat of quantum computers at least as many years in advance since cyber-criminals could intercept and cache the data and wait for the advent of quantum computers to crack the coded data.

Upping the game

The need to have secure systems in place years in advance of quantum computer systems is leading security experts and researchers to pursue two approaches to data security. One uses maths while the other is based on quantum physics.

Maths promises new algorithms that are not vulnerable to quantum computing. These are known as post-quantum or quantum-resistant techniques. Several approaches are being researched including lattice-based, coding-based and hash-function-based techniques. But these will take several years to develop. Moreover, such algorithms are deemed secure because they are based on sound maths that is resilient to algorithms run on quantum computers. But equally, they are secure because techniques to break them have not been widely investigated, by researchers and cyber criminals alike.

The second, physics approach uses quantum mechanics for key distribution across an optical link, which is inherently secure.

“Do you pin your hopes on a physics theory [quantum mechanics] that has been around for 100 years or do you base it on maths?” says BT’s Lord. “Or do you do both?”

In the world of the very small, things are linked, even though they are not next to each other

Quantum cryptography

One way to create a secure link is to send the information encoded on photons - particles of light. Here, each photon carries a single bit of the key.

If the adversary steals the photon, it is not received and, equally, they are taking information that is no use to them, says Lord. A more sophisticated technique is to measure the photon while it passes through but here they come up against the quantum mechanical effect where measuring a photon changes its parameters. The transmitter and receiver typically reserve at random a small number of the key’s photons to detect a potential eavesdropper. If the receiver detects photons that were not sent, the change alerts them that the link has been compromised.

The issue with such quantum key distribution techniques is that the distances a single photon can be sent are limited to a few tens of kilometres only. If longer links are needed, intermediate secure trusted sites are used to regenerate the key. These trusted sites need to be secure.

Entanglement, whereby two photons are created such that they are linked even if they are physically in separate locations, is one way researchers are looking to extend the distance keys can be distributed. With such entangled photons, any change or measurement of one instantly affects the twin photon. “In the world of the very small, things are linked, even though they are not next to each other,” says Lord.

Entanglement could be used by quantum repeaters to increase the length possible for key distribution not least for satellites, says Lord: “A lot of work is going on how to put quantum key distribution on orbiting satellites using entanglement.”

But quantum key distribution only solves a particular class of problem such as protecting data sent across links, backing up data between a bank and a data centre, for example. The technique is also dependent on light and thus is not as widely applicable as post-quantum algorithms. "There is a view emerging in the industry that you throw both of these techniques [post quantum algorithms and quantum key distribution] especially at data streams you want to keep secure."

Practicalities

BT working with Toshiba and optical transport equipment maker ADVA Optical Networking have already demonstrated a quantum protected link operating at 100 gigabits-per-second.

BT’s Lord says that while quantum cryptography has been a relatively dormant topic for the last decade, this is now changing. “There are lots of investment around the world and in the UK, with millions poured in by the government,” he says. BT is also encouraged that there are more companies entering the market including Huawei.

“What is missing is still a little bit more industrialisation,” says Lord. “Quantum physics is pretty sound but we still need to check that the way this is implemented, there are no ways of breaching it; to be honest we haven't really done that yet.”

BT says it has spent the last few months talking to financial institutions and claims there is much interest, especially with quantum computing getting much closer to commercialisation. “That is going to force people to make some decisions in the coming years,” says Lord.

IoT will drive chip design and new styles of computing

Looking back 20 years hence, how will this period be viewed? The question was posed by the CEO of imec, Luc Van de hove, during his opening talk at a day event imec organised in Tel-Aviv.

For Van den hove, this period will be seen as one of turbulent technological change. “The world is changing at an incredible rate,” he says. “The era of digital disruption is changing our industry and this disruption is not going to stop.”

Luc Van den hove

Luc Van den hove

It was the Belgium nonoelectronics R&D centre’s second visit to Israel to promote its chip and systems expertise as it seeks to expand its links with Israel’s high-tech industry. And what most excites imec is the Internet of Things (IoT), the advent of connected smart devices that turn data into information and adapt the environment to our needs.

The world is changing at an incredible rate. The era of digital disruption is changing our industry and this disruption is not going to stop

Internet of Things

Imec is focussing on five IoT areas: Smart Health - wearable and diagnostic devices, Smart Mobility which includes technologies for autonomous cars, drones and robots, Smart Cities, Smart Industry and Smart Energy. “In all these areas we look at how we can leverage our semiconductor know-how,” says Van den hove. “How we can bring innovative solutions by using our microchip technology.”

The broad nature of the IoT means imec must form partnerships across industries while strengthening its systems expertise. In healthcare, for example, imec is working with John Hopkins University, while last October, imec completed the acquisition of iMinds, a Belgium research centre specialising in systems software and security.

“One of the challenges of IoT is that there is not one big killer application,” says Van den hove. “How to bring these technologies to market is a challenge.” And this is where start-ups can play a role and explains why imec is visiting Israel, to build its partnerships with local high-tech firms.

Imec also wants to bring its own technologies to market through start-ups and has established a €100 million investment fund to incubate new ideas and spin-offs.

Technologies

Imec’s expertise ranges from fundamental semiconductor research to complex systems-on-chip. It is focussing on advanced sensor designs for IoT as this is where it feels it can bring an advantage. Imec detailed a radar chip design for cars that operates at 79GHz yet is implemented in CMOS. It is also developing a Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) chip for cars based on integrated photonics. Future cars will have between 50 to 100 sensors including cameras, LIDAR, radar and ultrasound.

Imec's multi-project wafers. Source: imec

Imec's multi-project wafers. Source: imec

The data generated from these sensors must be processed, fused and acted upon. Imec is doing work in the areas of artificial intelligence and machine learning. In particular, it is developing neuromorphic computing devices that use analogue circuits to mimic the biological circuitry of the brain. Quantum computing is another area imec has begun to explore.

One of the challenges of IoT is that there is not one big killer application

“There is going to be so much data generated,” says Van den Hove. “And it is better to do it [processing] locally because computation is cheaper than bandwidth.”

Imec envisages a network with layers of intelligence, from the sensors all the way to the cloud core. As much of the data as possible will be processed by the sensor so that it can pass on more intelligent information to the network edge, also known as fog computing. Meanwhile, the cloud will be used for long-term data storage, for historical trending and for prediction using neuromorphic algorithms, says Van den Hove.

But to perform intensive processing on-chip and send the results off-chip in a power-efficient manner will require advances in semiconductor technology and the continuation of Moore’s law.

Moore's law

Imec remains confident that Moore’s law will continue to advance for some years yet but notes it is getting harder. In the past, semiconductor technology had a predictable roadmap such that chip designers could plan ahead and know their design goals would be met. Now chip technologists and designers must work together, a process dubbed technology-design co-optimisation.

Van den hove cites the example of imec’s work with ARM Holdings to develop a 7nm CMOS process node. “You can create some circuit density improvement just by optimising the design, but you need some specific technology features to do that,” he says. For example, by using a self-alignment technique, fewer metal tracks can be used when designing a chip's standard cell circuitry. "Using the same pitch you get an enormous shrink," he says. But even that is not going to be enough and techniques such as system-technology co-optimisation will be needed.

Imec is working on FinFETs, a style of transistor, to extend CMOS processes down to 5nm and then sees the use of silicon nanowire technology - first horizontal and then vertical designs - to extend the roadmap to 3nm, 2.5nm and even 1.8nm feature sizes.

Imec is also working on 3D chip stacking techniques that will enable multi-layer circuits to be built. “You can use specific technologies for the SRAM, processing cores and the input-output.” Imec is an active silicon photonics player, seeing the technology playing an important role for optical interconnect.

Imec awarded Gordon Moore a lifetime of innovation award last year, and Van den hove spent an afternoon at Moore’s home in Hawaii. Van den hove was struck with Moore’s humility and sharpness: “He was still so interested in the technology and how things were going.”

Intelligent networking: Q&A with Alcatel-Lucent's CTO

Alcatel-Lucent's corporate CTO, Marcus Weldon, in a Q&A with Gazettabyte. Here, in Part 1, he talks about the future of the network, why developing in-house ASICs is important and why Bell Labs is researching quantum computing.

Marcus Weldon (left) with Jonathan Segel, executive director in the corporate CTO Group, holding the lightRadio cube. Photo: Denise Panyik-Dale

Marcus Weldon (left) with Jonathan Segel, executive director in the corporate CTO Group, holding the lightRadio cube. Photo: Denise Panyik-Dale

Q: The last decade has seen the emergence of Asian Pacific players. In Asia, engineers’ wages are lower while the scale of R&D there is hugely impressive. How is Alcatel-Lucent, active across a broad range of telecom segments, ensuring it remains competitive?

A: Obviously we have a Chinese presence ourselves and also in India. It varies by division but probably half of our workforce in R&D is in what you would consider a low-cost country. We are already heavily present in those areas and that speaks to the wage issue.

But we have decided to use the best global talent. This has been a trait of Bell Labs in particular but also of the company. We believe one of our strengths is the global nature of our R&D. We have educational disciplines from different countries, and different expertise and engineering foci etc. Some of the Eastern European nations are very strong in maths, engineering and device design. So if you combine the best of those with the entrepreneurship of the US, you end up with a very strong mix of an R&D population that allows for the greatest degree of innovation.

We have no intention to go further towards a low-cost country model. There was a tendency for that a couple of years ago but we have pulled back as we found that we were losing our innovation potential.

We are happy with the mix we have even though the average salary is higher as a result. And if you take government subsidies into account in European nations, you can get almost the same rate for a European engineer as for a Chinese engineer, as far as Alcatel-Lucent is concerned.

One more thing, Chinese university students, interestingly, work so hard up to getting into university that university is a period where they actually slack off. There are several articles in the media about this. The four years that students spend in university, away from home for the first time, they tend to relax.

Chinese companies were complaining that the quality of engineers out of university was ever decreasing because of what was essentially a slacker generation, they were arguing, of overworked high-school students that relaxed at college. Chinese companies found that they had to retrain these people once employed to bring them to the level needed.

So that is another small effect which you could argue is a benefit of not being in China for some of our R&D.

Alcatel-Lucent's Bell Labs: Can you spotlight noteworthy examples of research work being done?

Certainly the lightRadio cube stuff is pure Bell Labs. The adaptive antenna array design, to give you an example, was done between the US - Bell Labs' Murray Hill - and Stuttgart, so two non-Asian sites at Bell Labs involved in the innovations. These are wideband designs that can operate at any frequencies and are technology agnostic so they can operate for GSM, 3G and LTE (Long Term Evolution).

"We believe that next-generation network intelligence, 10-15 years from now, might rely on quantum computing"

The designs can also form beams so you can be very power-efficient. Power efficiency in the antenna is great as you want to put the power where it is needed and not just have omni (directional) as the default power distribution. You want to form beams where capacity is needed.

That is clearly a big part of what Bell Labs has been focussing on in the wireless domain as well as all the overlaying technologies that allow you to do beam-forming. The power amplifier efficiency, that is another way you lose power and you operate at a more costly operational expense. The magic inside that is another focus of Bell Labs on wireless.

In optics, it is moving from 100 Gig to 400 Gig coherent. We are one of the early innovators in 100 Gig coherent and we are now moving forward to higher-order modulation and 400 Gig.

On the DSL side it the vectoring/ crosstalk cancellation work where we have developed our own ASIC because the market could not meet the need we had. The algorithms ended up producing a component that will be in the first release of our products to maintain a market advantage.

We do see a need for some specialised devices like the FlexPath FP3 network processor, the IPTV product, the OTN (Optical Transport Network) switch that is at the heart of our optical products is our own ASIC, and the vectoring/ crosstalk cancellation engine in our DSL products. Those are the innovations Bell Labs comes up with and very often they lead to our portfolio innovations.

There is also a lot of novel stuff like quantum computing that is on the fringes of what people think telecoms is going to leverage but we are still active in some of those forward-looking disciplines.

We have quite a few researchers working on quantum computing, leveraging some of the material expertise that we have to fabricate novel designs in our lab and then create little quantum computing structures.

Why would quantum computing be useful in telecom?

It is very good for parsing and pattern matching. So when you are doing complex searches or analyses, then quantum computing comes to the fore.

We do believe there will be processing that will benefit from quantum computing constructs to make decisions in ever-increasingly intelligent networks. Quantum computing has certain advantages in terms of its ability to recognise complex states and do complex calculations. We believe that next-generation network intelligence, 10-15 years from now, might rely on quantum computing.

We don't have a clear application in mind other than we believe it is a very important space that we need to be pioneering.

"Operators realise that their real-estate resource - including down to the central office - is not the burden that it appeared to be a couple of years ago but a tremendous asset"

You wrote a recent blog on the future of the network. You mentioned the idea of the emergence of one network with the melding of wireless and wireline, and that this will halve the total cost of ownership. This is impressive but is it enough?

The half number relates to the lightRadio architecture. There are many ingredients in it. The most notable is that traffic growth is accounted for in that halving of the total cost of ownership. We calculated what the likely traffic demand would be going forward: a 30-fold increase in five years.

Based on that growth, when we computed how much the lightRadio architecture, involving the adaptive antenna arrays, small cells and the move to LTE, if you combine these things and map it into traffic demand, the number comes up that you can build the network for that traffic demand and with those new technologies and still halve the total cost of ownership.

It really is quite a bit more aggressive than it appears because it is taking account of a very significant growth in traffic.

Can we build that network and still lower the cost? The answer is yes.

You also say that intelligence will be increasingly distributed in the network, taking advantage of Moore's Law. This raises two questions. First, when does it make sense to make your own ASICs?

When I say ASICs I include FPGAs. FPGAs are your own design just on programmable silicon and normally you evolve that to an ASIC design once you get to the right volumes.

There is a thing called an NRE (non-recurring engineering) cost, a non-refundable engineering cost to product an ASIC in a fab. So you have to have a certain volume that makes it worthwhile to produce that ASIC, rather than keeping it in an FPGA which is a more expensive component because it is programmable and has excess logic. On the other hand, there is economics that says an FPGA is the right way for sub-10,000 volumes per annum whereas for millions of parts you would do an ASIC.

We work on both those types of designs. And generally, and I think even Huawei would agree with us, a lot of the early innovation is done in FPGAs because you are still playing with the feature set.

Photo: Denise Panyik-Dale

Photo: Denise Panyik-Dale

Often there is no standard at that point, there may be preliminary work that is ongoing, so you do the initial innovation pre-standard using FPGAs. You use a DSP or FPGA that can implement a brand new function that no one has thought of, and that is what Bell Labs will do. Then, as it starts becoming of interest to the standard bodies, you have it implemented in a way that tries to follow what the standard will be, and you stay in a FPGA for that process. At some point later, you take a bet that the functionality is fixed and the volume will be high enough, and you move to an ASIC.

So it is fairly commonplace for novel technology to be implemented by the [system] vendors. And only in the end stage when it has become commoditised to move to commercial silicon, meaning a Broadcom or a Marvell.

Also around the novel components we produce there are a whole host of commercial silicon components from Texas Instruments, Broadcom, Marvell, Vitesse and all those others. So we focus on the components where the magic is, where innovation is still high and where you can't produce the same performance from a commercial part. That is where we produce our own FPGAs and ASICs.

Is this trend becoming more prevalent? And if so, is it because of the increasing distribution of intelligence in network.

I think it is but only partly because of intelligence. The other part is speed. We are reaching the real edges of processing speed and generally the commercial parts are not at that nanometer of [CMOS process] technology that can keep up.

To give an example, our FlexPath processor for the router product we have is on 40nm technology. Generally ASICs are a technology generation behind FPGAs. To get the power footprint and the packet-processing performance we need, you can't do that with commercial components. You can do it in a very high-end FPGA but those devices are generally very expensive because they have extremely low yields. They can cost hundreds or thousands of dollars.

The tendency is to use FPGAs for the initial design but very quickly move to an ASIC because those [FGPA] parts are so rare and expensive; nor do they have the power footprint that you want. So if you are running at very high speeds - 100Gbps, 400Gbps - you run very hot, it is a very costly part and you quickly move to an ASIC.

Because of intelligence [in the network] we need to be making our own parts but again you can implement intelligence in FPGAs. The drive to ASICs is due to power footprint, performance at very high speeds and to some extent protection of intellectual property.

FPGAs can be reverse-engineered so there is some trend to use ASICs to protect against loss of intellectual property to less salubrious members of the industry.

Second, how will intelligence impact the photonic layer in particular?

You have all these dimensions you can trade off each other. There are things like flexible bit-rate optics, flexible modulation schemes to accommodate that, there is the intelligence of soft-decision FEC (forward error correction) where you are squeezing more out of a channel but not just making it a hard-decision FEC - is it a '0' or a '1' but giving a hint to the decoder as to whether it is likely to be a '0' or a '1'. And that improves your signal-to-noise ratio which allows you to go further with a given optics.

So you have several intelligent elements that you are going to co-ordinate to have an adaptive optical layer.

I do think that is the largest area.

Another area is smart or next-generation ROADMs - we call it connectionless, contentionless, and directionless.

There is a sense that as you start distributing resources in the network - cacheing resources and computing resources - there will be far more meshing in the metro network. There will be a need to route traffic optically to locally positioned resources - highly distributed data centre resources - and so there will be more photonic switching of traffic. Think of it as photonic offload to a local resource.

We are increasingly seeing operators realise that their real-estate resource - including down to the central office - is not the burden that it appeared to be a couple of years ago but a tremendous asset if you want to operate a private cloud infrastructure and offer it as a service, as you are closer to the user with lower latency and more guaranteed performance.

So if you think about that infrastructure, with highly distributed processing resources and offloading that at the photonic layer, essentially you can easily recognise that traffic needs to go to that location. You can argue that there will be more photonic switching at the edge because you don't need to route that traffic, it is going to one destination only.

This is an extension of the whole idea of converged backbone architecture we have, with interworking between the IP and optical domains, you don't route traffic that you don't need to route. If you know it is going to a peering point, you can keep that traffic in the optical domain and not send it up through the routing core and have it constantly routed when you know from the start where it is going.

So as you distribute computing and cacheing resources, you would offload in the optical layer rather than attempt to packet process everything.

There are smarts at that level too - photonic switching - as well as the intelligent photonic layer.

For the second part of the Q&A, click here