The ONF adapts after sale of spin-off Ananki to Intel

Intel’s acquisition of Ananki, a private 5G networking company set up within the ONF last year, has meant the open-model organisation has lost the bulk of its engineering staff.

The ONF, a decade-old non-profit consortium led by the telecom operators, has developed some notable networking projects over the years such as CORD, OpenFlow, one of the first software-defined networking (SDN) standards, and Aether, the 5G edge platform.

Its joint work with the operators has led to virtualised and SDN building blocks that, when combined, can address comprehensive networking tasks such as 5G, wireline broadband and private wireless networks.

The ONF’s approach has differed from other open-source organisations. Its members pay for an in-house engineering team to co-develop networking blocks based on disaggregation, SDN and cloud.

The ONF and its members have built a comprehensive portfolio of networking functions which last year led to the organisation spinning out a start-up, Ananki, to commercialise a complete private end-to-end wireless network.

Now Intel has acquired Ananki, taking with it 44 of the ONF’s 55 staff.

“Intel acquired Ananki, Intel did not acquire the ONF,” says Timon Sloane, the ONF’s newly appointed general manager. “The ONF is still whole.”

The ONF will now continue with a model akin to other open-source organisations.

ONF’s evolution

The ONF began by tackling the emerging interest in SDN and disaggregation.

“After that phase, considered Phase One, we broke the network into pieces and it became obvious that it was complicated to then build solutions; you have these pieces that had to be reassembled,” says Sloane.

The ONF used its partner funding to set up a joint development team to craft solutions that were used to seed the industry.

The ONF pursued this approach for over six years but Sloane said that it felt increasingly that the model had run its course.“We were kind of an insular walled garden, with us and a small number of operators working on things,” says Sloane. “We needed to flip the model inside out and go broad.”

This led to the spin-out of Ananki, a separate for-profit entity that would bring in funding yet would also be an important contributor to open source. And as it grew, the thinking was that it would subsume some of the ONF’s engineering team.

“We thought for the next phase that a more typical open-source model was needed,” says Sloane. “Something like Google with Kubernetes, where one company builds something, puts it in open source and feeds it, even for a couple of years, until it grows, and the community grows around it.”

But during the process of funding Ananki, several companies expressed an interest in acquiring the start-up. The ONF will not say the other interested players but hints that it included telecom operators and hyperscalers.

The merit of Intel, says Sloane, is that it is a chipmaker with a strong commitment to open source.

Deutsche Telekom’s ongoing ORAN trial in Berlin uses key components from the ONF including the SD-Fabric, 5G and 4G core functions, and the uONOS near real-time RAN Intelligent controller (RIC). Source: ONF, DT.

Deutsche Telekom’s ongoing ORAN trial in Berlin uses key components from the ONF including the SD-Fabric, 5G and 4G core functions, and the uONOS near real-time RAN Intelligent controller (RIC). Source: ONF, DT.

Post-Ananki

“Those same individuals who were wearing an ONF hat, are swapping it for an Intel hat, but are still on the leadership of the project,” says Sloane. “We view this as an accelerant for the project contributions because Intel has pretty deep resources and those individuals will be backed by others.”

The ONF acknowledges that its fixed broadband passive optical networking (PON) work is not part of Ananki’s interest. Intel understands that there are operators reliant on that project and will continue to help during a transition period. Those vendors and operators directly involved will also continue to contribute.

“If you look at every other project that we’re doing: mobile core, mobile RAN, all the P4 work, programmable networks, Intel has been very active.”

Meanwhile, the ONF is releasing its entire portfolio to the open-source community.

“We’ve moved out of the walled-garden phase into a more open phase, focused on the consumption and adoption [of the designs,” says Sloane. The projects will stay remain under the auspices of the ONF to get the platforms adopted within networks.

The ONF will use its remaining engineers to offer its solutions using a Continuous Integration/ Continuous Delivery (CI/CD) software pipeline.

“We will continue to have a smaller engineering team focused on Continuous Integration so that we’ll be able to deliver daily builds, hourly builds, and continuous regression testing – all that coming out of ONF and the ONF community,” says Sloane. “Others can use their CD pipelines to deploy and we are delivering exemplar CD pipelines if you want to deploy bare metal or in a cloud-based model.”

The ONF is also looking at creating a platform that enables the programmability of a host using silicon such as a data processing unit (DPU) as part of larger solutions.

“It’s a very exciting space,” says Sloane. “You just saw the Pensando acquisition; I think that others are recognising this is a pretty attractive space.” AMD recently announced it is acquiring Pensando, to add a DPU architecture to AMD’s chip portfolio.

The ONF’s goal is to create a common platform that can be used for cloud and telecom networking and infrastructure for applications such as 5G and edge.

“And then there is of course the whole edge space, which is quite fascinating; a lot is going on there as well,” says Sloane. “So I don’t think we’re done by any means.”

Deutsche Telekom's Access 4.0 transforms the network edge

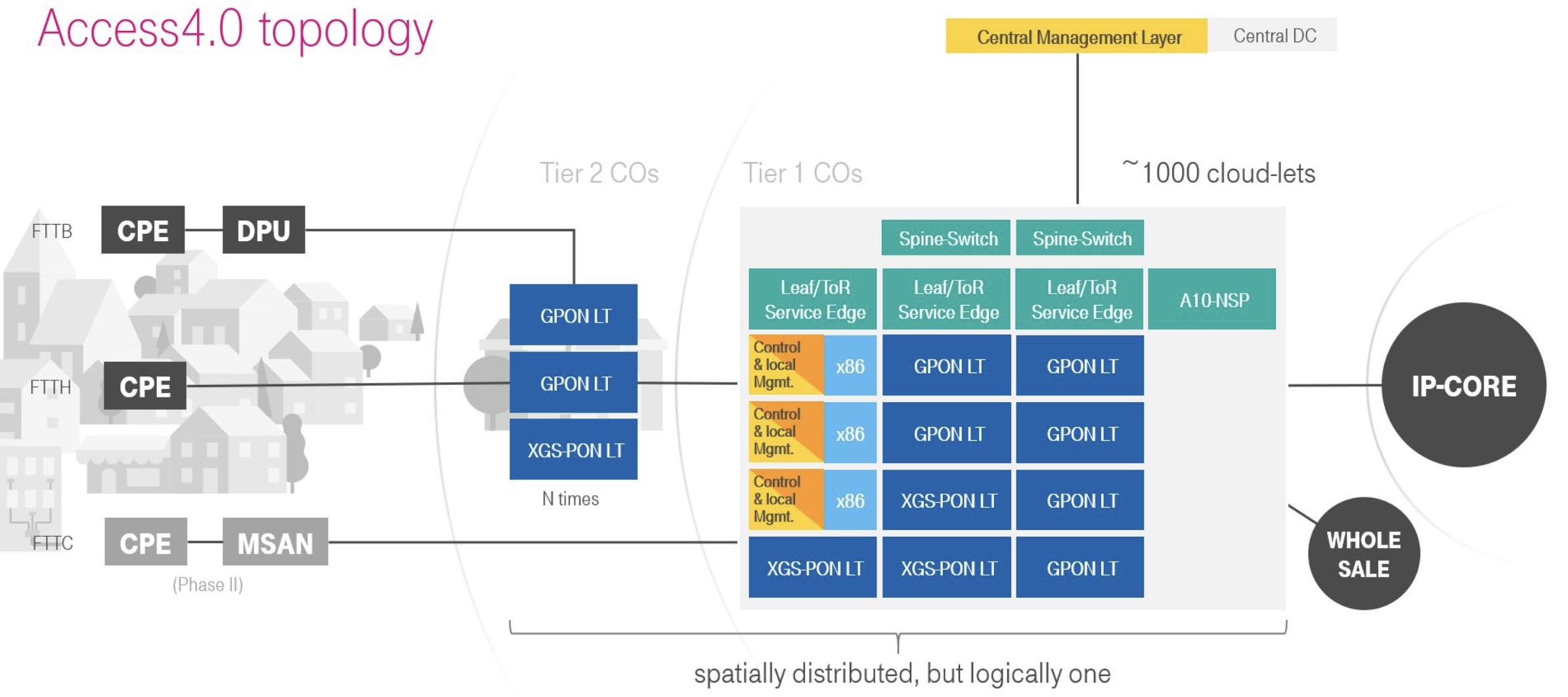

Deutsche Telekom has a working software platform for its Access 4.0 architecture that will start delivering passive optical network (PON) services to German customers later this year. The architecture will also serve as a blueprint for future edge services.

Access 4.0 is a disaggregated design comprising open-source software and platforms that use merchant chips – ‘white-boxes’ – to deliver fibre-to-the-home (FTTH) and fibre-to-the-building (FTTB) services.

“One year ago we had it all as prototypes plugged together to see if it works,” says Hans-Jörg Kolbe, chief engineer and head of SuperSquad Access 4.0. “Since the end of 2019, our target software platform – a first end-to-end system – is up and running.”

Deutsche Telekom has about 1,000 central office sites in Germany, several of which will be upgraded this year to the Access 4.0 architecture.

“Once you have a handful of sites up and running and you have proven the principle, building another 995 is rather easy,” says Robert Soukup, senior program manager at Deutsche Telekom, and another of the co-founders of the Access 4.0 programme.

Origins

The Access 4.0 programme emerged with the confluence of two developments: a detailed internal study of the costs involved in building networks and the advent of the Central Office Re-architected as a Datacentre (CORD) industry initiative.

Deutsche Telekom was scrutinising the costs involved in building its networks. “Not like removing screws here and there but looking at the end-to-end costs,” says Kolbe.

Separately, the operator took an interest in CORD that was, at the time, being overseen by ON.Labs.

At first, Kolbe thought CORD was an academic exercise but, on closer examination, he and his colleague, Thomas Haag, the chief architect and the final co-founder of Access 4.0, decided the activity needed to be investigated internally. In particular, to assess the feasibility of CORD, how bringing together cloud technologies with access hardware would work, and quantify the cost benefits.

“The first goal was to drive down cost in our future network,” says Kolbe. “And that was proven in the first month by a decent cost model. Then, building a prototype and looking into it, we found more [cost savings].”

Given the cost focus, the operator hadn’t considered the far-reaching changes involve with adopting white boxes and the disaggregation of software and hardware, nor the consequences of moving to a mainly software-based architecture in how it could shorten the introduction of new services.

“I knew both these arguments were used when people started to build up Network Functions Virtualisation (NFV) but we didn’t have this in mind; it was a plain cost calculation,” says Kolbe. “Once we starting doing it, however, we found both these things.”

Cost engineering

Deutsche Telekom says it has learnt a lot from the German automotive industry when it comes to cost engineering. For some companies, cost is part of the engineering process and in others, it is part of procurement.

“The issue is not talking to a vendor and asking for a five percent discount on what we want it to deliver,” says Soukup, adding that what the operator seeks is fair prices for everybody.

“Everyone needs to make a margin to stay in business but the margin needs to be fair,” says Soukup. “If we make with our customers a margin of ’X’, it is totally out of the blue that our vendors get a margin of ‘10X’.”

The operator’s goal with Access 4.0 has been to determine how best to deploy broadband internet access on a large scale and with carrier-grade quality. Access is an application suited to cost reduction since “the closer you come to the customer, the more capex [capital expenditure] you have to spend,” says Soukup, adding that since capex is always less than what you’d like, creativity is required.

“When you eat soup, you always grasp a spoon,” says Soukup. “But we asked ourselves: ‘Is a spoon the right thing to use?’”

Software and White Boxes

Access 4.0 uses two components from the Open Networking Foundation (ONF): Voltha and the Software Defined Networking (SDN) Enabled Broadband Access (SEBA) reference design.

Voltha provides a common control and management system for PON white boxes while making the PON network appear to the SDN controller that resides above as a programmable switch. “It abstracts away the [PON] optical line terminal (OLT) so we can treat it as a switch,” says Soukup

SEBA supports a range of fixed broadband technologies that include GPON and XGS-PON. “SEBA 2.0 is a design we are using and are compliant,” says Soukup.

“We are bringing our technology to geographically-distributed locations – central offices – very close to the customer,” says Kolbe. Some aspects are common with the cloud technology used in large data centres but there are also differences.

For example, virtualisation technologies such as Kubernetes are shared while large data centres use OpenStack which is not needed for Access 4.0. In turn, a leaf-spine switching architecture is common as is the use of SDN technology.

“One thing we have learned is that you can’t just take the big data centre technology and put it in distributed locations and try to run heavy-throughput access networks on them,” says Kolbe. “This is not going to work and it led us to the white box approach.”

The issue is that certain workloads cannot be tackled efficiently using x86-based server processors. An example is the Broadband Network Gateway (BNG). “You need to do significant enhancements to either run on the x86 or you offload it to a different type of hardware,” says Kolbe.

Deutsche Telekom started by running a commercial vendor’s BNG on servers. “In parallel, we did the cost calculation and it was horrible because of the throughput-per-Euro and the power-per-Euro,” says Kolbe. And this is where cost engineering comes in: looking at the system, the biggest cost driver was the servers.

“We looked at the design and in the data path there are three programmable ASICs,” says Kolbe. “And this is what we did; it is not a product yet but it is working in our lab and we have done trials.” The result is that the operator has created an opportunity for a white-box design.

There are also differences in the use of switching between large data centres and access. In large data centres, the switching supports the huge east-west traffic flows while in carrier networks, especially close to the edge, this is not required.

Instead, for Access 4.0, traffic from PON trees arrives at the OLT where it is aggregated by a chipset before being passed on to a top-of-rack switch where aggregation and packet processing occur.

The leaf-and-spine architecture can also be used to provide a ‘breakout’ to support edge-cloud services such as gaming and local services. “There is a traffic capability there but we currently don’t use it,” says Kolbe. “But we are thinking that in the future we will.”

Deutsche Telekom has been public about working with such companies as Reply, RtBrick and Broadcom. Reply is a key partner while RtBrick contributes a major element of the speciality domain BNG software.

Kolbe points out that there is no standard for using network processor chips: “They are all specific which is why we need a strong partnership with Broadcom and others and build a common abstraction layer.”

Deutsche Telekom also works closely with Intel, incumbent network vendors such as ADTRAN and original design manufacturers (ODMs) including EdgeCore Networks.

Challenges

About 80 percent of the design effort for Access 4.0 is software and this has been a major undertaking for Deutsche Telekom.

“The challenge is to get up to speed with software; that is not a thing that you just do,” says Kolbe. “We can’t just pretend we are all software engineers.”

Deutsche Telekom also says the new players it works with – the software specialists – also have to better understand telecom. “We need to meet in the middle,” says Kolbe.

Soukup adds that mastering software takes time – years rather than weeks or months – and this is only to be expected given the network transformation operators are undertaking.

But once achieved, operators can expect all the benefits of software – the ability to work in an agile manner, continuous integration/ continuous delivery (CI/DC), and the more rapid introduction of services and ideas.

“This is what we have discovered besides cost-savings: becoming more agile and transforming an organisation which can have an idea and realise it in days or weeks,” says Soukup. The means are there, he says: “We have just copied them from the large-scale web-service providers.”

Status

The first Access 4.0 services will be FTTH delivered from a handful of central offices in Germany later this year. FTTB services will then follow in early 2021.

“Once we are out there and we have proven that it works and it is carrier-grade, then I think we are very fast in onboarding other things,” says Soukup. “But they are [for now] not part of our case.”

Edgecore exploits telecom’s open-networking opportunity

Edgecore Networks is expanding its open networking portfolio with cell-site gateways and passive optical networking (PON) platforms.

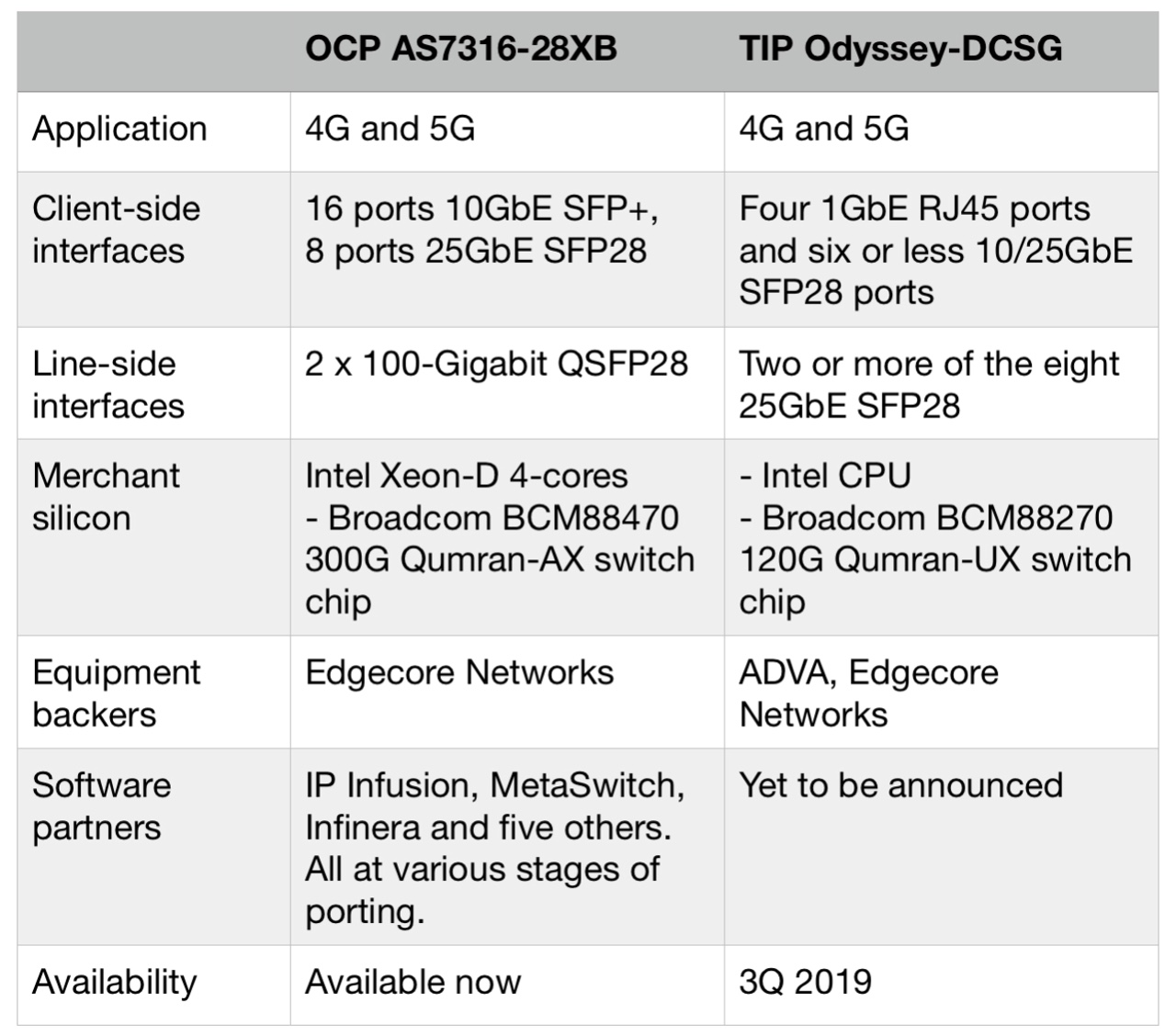

The company is backing two cell-site gateway designs that aggregate traffic from baseband units for 4G and 5G mobile networks. One design is from the Open Compute Project (OCP) that is available now and the second is from the Telecom Infra Project (TIP) that is planned for 2019 (see table).

Edgecore has also announced PON optical line terminal (OLT) platforms addressing 10-gigabit XGS-PON and GPON.

Source: ADVA, Edgecore Networks

Source: ADVA, Edgecore Networks

Edgecore is a wholly-ownedsubsidiary of Accton Technology, a Taiwanese original design manufacturer (ODM) employing over 700 networking engineers that reported revenues exceeding $1.2 billion in 2017.

Open networking

Edgecore is a leading proponent of open networking that first data centre operators and now telecom operators are adopting.

Open networking refers to disaggregated designs where the hardware and software comes from separate companies. The hardware is a standardised white box developed in an open framework, while the accompanying software can be commercial code from a company or open-sourced.

Our focus is on all those attributes of open networking: disaggregation, the hardware and software design of standard platforms, and making those designs open

Telecom networks have traditionally been built using proprietary equipment from systems vendors that includes the complete software stack. But the leading telcos have moved away from this approach to avoid being locked into a systems vendor's roadmap. Instead, they are active in open frameworks and are embracing disaggregated open designs, having seen the benefits achieved by the internet content providers that pioneered the approach.

“The IT industry for years have been buying servers and purposing them for whatever application they are designated for, adding an operating system and application software on top,” says Mark Basham, vice president business development and marketing, EMEA at Edgecore. “Now we are seeing the telecom industry shift to that model; they see where the value should be.”

White-box platforms built using merchant silicon promise to reduce the number of specialised platforms in an operator’s network, reducing costs by simplifying platform qualification and support.

“Our focus is on all those attributes of open networking: disaggregation, the hardware and software design of standard platforms, and making those designs open,” says Bill Burger, vice president, business development and marketing for North America at Edgecore.

OCP, TIP and ONF

Edgecore is active in three leading open framework initiatives whose memberships include large-scale data centre operators, telcos, equipment makers, systems integrators, software partners and chip players.

Edgecore is a member of OCP that was founded to address the data centre but now plays an important role in telecoms. The company is also part of TIP that was established in 2016 and includes internet giants Facebook and Microsoft as well as leading telecom operators, systems vendors, components players and others. Edgecore is also a key white-box partner as part of the Open Networking Foundation’s (ONF) reference-design initiative.

Edgecore Networks' involvement in the ONF's reference design projects. Diagram first published in July 2018. Source: ONF.

Edgecore Networks' involvement in the ONF's reference design projects. Diagram first published in July 2018. Source: ONF.

Cell-site gateways

Edgecore has announced the availability of its AS7316-26XB, the industry’s first open cell-site gateway white-box design from the OCP that originated as an AT&T specification.

The company is also active in TIP’s cell-site gateway initiative. Edgecore will make and market the Odyssey Disaggregated Cell Site Gateway (Odyssey-DCSG) design that is backed by TIP’s operator members Telefonica, Orange, TIM Brazil and Vodafone. BT is also believed to be backing the TIP gateway.

The gateway aggregates the radio baseband unit (BBU) at a cell site back into the transport network.

The OCP cell-site gateway has a more advanced specification compared to the Odyssey. The AS7316-26XB uses a more powerful Intel processor and employs a 300-gigabit Broadcom Qumran-AX switch chip that aggregates the baseband traffic for transmission into the network.

The platform’s client-side interfaces include 16 SFP+ ports that supports either 1 Gigabit Ethernet (GbE) SFP or 10GbE SFP+ pluggable modules, eight 25GbE ports that accommodate either 10GbE SFP+ or 25GbE SFP28 modules, and two 100GbE QSFP28 uplinks. Some of the 25GbE ports could be used to expand the uplink capacity, if needed.

In contrast, the TIP Odyssey-DCSG platform uses a 120-gigabit Qumran switch chip while its interfaces include provide four 1GbE RJ45 ports and eight 10GbE or 25GbE SFP28 ports. Accordingly, the platform’s uplinks are at 25GbE.

“They [the OCP and TIP gateways] are very different boxes in terms of their performance,” says Basham.

Current deployed mobile platforms don't have sufficient capacity to support LTE Advanced Pro, never mind 5G, says Basham: “All the operators are looking at what is the right time to insert these boxes in the network.”

Telcos need to decide how much they are willing to spend up front. They could deploy a larger capacity but costlier cell-site gateway to future-proof their mobile backhaul for up to a decade. Or they could install the smaller-capacity Odyssey-DCSG that will suffice for five years before requiring an upgrade.

Given that the largest operators will deploy the gateways in units of hundreds of thousands, the capital expenditure outlay will be significant.

Basham says there will be a family of cell-site gateways and points out that the TIP specification originally had three ‘service configurations’. The latest TIP specification document now has a fourth service configuration that differs significantly from the other three in its port count and capabilities. “It shows that there is no one-size-fits-all,” says Basham.

The company also has announced two open disaggregated PON products, part of the OCP.

The ASXvOLT16 is a 10-gigabit OLT platform that supports XGS-PON and NG-PON2. The open OLT platform uses Broadcom’s 800-gigabit Qumran-MX switch chip and its BCM68620 Maple OLT device.

The platform’s interfaces includes 16 XFP ports supporting 10-gigabit optics while for the uplink traffic, four 100GbE ports are used. Each 10-gigabit interface will support 32 or 64 PON optical network units (ONU) typically.

“To support NG-PON2 will require the virtual OLT hardware abstraction layer to be adapted slightly, and also firmware to be put on the Broadcom chips,” says Basham. “The big difference between XGS-PON and NG-PON2 is in the plug-in optics.” More costly tunable optics will be required for NG-PON2. The 1 rack unit (1RU) PON OLT design is available now.

Edgecore has also contributed GPON OLT designs that conform with Deutsche Telecom’s Open GPON OLT design. The Edgecore ASGvOLT32 and ASGvOLT64 GPON OLTs support 32- and 64-GPON ports, respectively, while there are two 100GbE and eight 25GbE uplink ports.

The two GPON OLTs will sample in the first quarter of 2019, moving to volume production one quarter later.

We are at the cusp of bringing together all the parts to make Cassini a deployable solution

Cassini

Edgecore is also bringing its Cassini packet-optical transport white-box platform to market.

Like TIP’s Voyager box, Cassini uses the Broadcom StrataXGS Tomahawk 3.2-terabit switch chip. But while the Voyager comes with built-in coherent interfaces based on Acacia’s AC-400 module, Cassini is a modular design that has eight card slots. Each slot can accommodate one of three module options: a coherent CFP2-ACO, a coherent CFP2-DCO or two QSFP28 100-gigabit pluggables. The Cassini platform also has 16 fixed QSFP28 ports.

Accordingly, the 1.5RU Cassini box can be configured using only the coherent interfaces required. The box could be set up as a 3.2-terabit switch using QSFP28 modules only or as a transport box with up to 1.6 terabits of client-side interfaces and 1.6 terabits of line-side coherent interfaces. This contrasts with the 1RU Voyager that offers 2 terabits of switch capacity with its dozen 100-gigabit client-side interfaces and 800 gigabits of coherent line-side capacity.

“We are at the cusp of bringing together all the parts to make Cassini a deployable solution,” says Basham. “The focus is to get it deployed in the market.”

Edgecore sees Cassini as a baseline for future products. One obvious direction is to increase the platform’s capacity using Broadcom’s 12.8-terabit Tomahawk 3 switch chip. Edgecore already offers a Tomahawk 3-based switch for the data centre.

Such a higher-capacity Cassini platform would support 400GbE client-side interfaces and 400- or 800-gigabit coherent line-side interfaces. “We think that there is a future need for such a platform but we are not actively developing it right now,” says Burger.

A second direction for Cassini’s development is as a platform suited to routeing using larger look-up tables and deep buffering. Such a platform would use merchant silicon such as Broadcom’s Jericho chip. “We think there is a need for that as service providers deploy packet transport platforms in their networks,” says Burger.

Business model

The Cassini platform arose as part of Edgecore’s detailed technology planning discussions with its leading internet content provider customers.

“We recognised a need for more modularity in an open-packet transponder, the ability to mix-and-match the number of packet switching interfaces with the coherent optical interfaces,” says Burger.

Edgecore then approached TIP before contributing the Cassini platform to the organisation’s Open Optical and Packet Transport group.

When Edgecore contributes a design to an open framework such as the OCP or TIP, the design undergoes a review resulting in valuable feedback from member companies.

“We end up making modifications to improve the design in some cases and it then goes through an approval process,” says Burger. “After that, we contribute the design package and its available to anyone without any royalty obligation.”

At first glance, it is not obvious how contributing a platform design that other firms can build benefits Edgecore. But Burger says Edgecore benefits is several ways.

The organisation members’ feedback improves the product’s design. Edgecore also raises industry awareness of its platforms including among the OCP’s and TIP’s large service provider members.

Making the design available to members also offers the operators a potential second source for Edcore’s white box designs, strengthening confidence and their appeal.

And once a design is open sourced, software partners including start-ups will investigate the design as a platform for their code which can result in partnerships. “This benefits us and benefits the software companies,” says Burger.

Edgecore stresses that open-networking platforms are going to take time before they become widely adopted across service providers’ networks.

“It is going to be an evolution, starting with high-volume, more standardised use cases,” concludes Burger.

Part 1: TIP white-box designs, click here