The CFP2 pluggable module gains industry momentum

Finisar and Oclaro unveiled their first CFP2 optical transceiver products at the recent ECOC exhibition in Amsterdam. JDSU also announced that its ONT-100G test equipment now supports the latest 100Gbps module form factor.

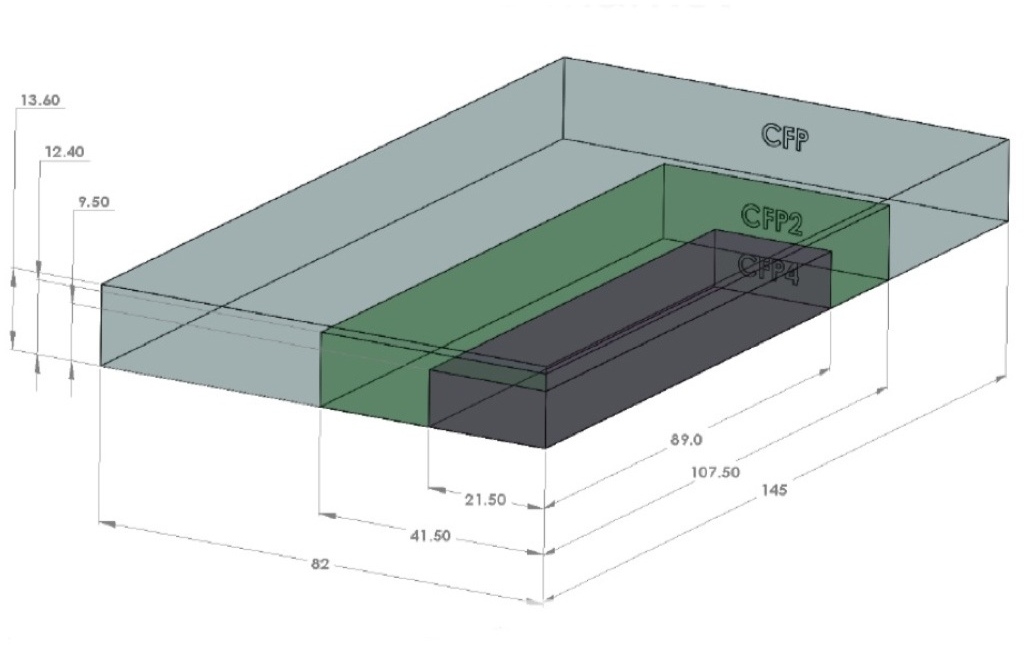

Source: Oclaro

Source: Oclaro

The CFP2 is the follow-on module to the CFP, supporting the IEEE 100 Gigabit Ethernet and ITU OTU4 standards. It is half the size of the CFP (see image) and typically consumes half the power. Equipment makers can increase the front-panel port density from four to eight by migrating to the CFP2.

Oclaro also announced a second-generation CFP supporting the 100GBASE-LR4 10km and OTU4 standards that reduces the power consumption from 24W to 16W. The power saving is achieved by replacing a two-chip silicon-germanium 'gearbox' IC with a single CMOS chip. The gearbox translates between the 10x10Gbps electrical interface and the 4x25Gbps signals interfacing to the optics.

The CFP2, in contrast, doesn’t include the gearbox IC.

"One of the advantages of the CFP2 module is we have a 4x25Gbps electrical interface," says Rafik Ward, vice president of marketing at Finisar. "That means that within the CFP2 module we can operate without the gearbox chip." The result is a compact, lower-power design, which is further improved by the use of optical integration.

"That 2.5x faster [interface of the CFP2] equates to about a 6x greater difficulty in signal integrity issues, microwave techniques etc"

Paul Brooks, JDSU

The transmission part of the CFP module typically comprises four externally modulated lasers (EMLs), each individually cooled. The four transmitter optical sub-assemblies (TOSAs) then interface to a four-channel optical multiplexer.

Finisar's CFP2 design uses a single TOSA holding four distributed feedback (DFB) lasers, a shared thermo-electric cooler and the multiplexer. The result of using DFBs and an integrated TOSA is that Finisar's CFP2 consumes just 8W.

Oclaro uses photonic integration on the receiver side, integrating four receiver optical sub-assemblies (ROSAs) as well as the optical demultiplexer into a single design, resulting in a 12W CFP2.

At ECOC, Oclaro demonstrated interoperability between its latest CFP and the CFP2. “It shows that the new modules will talk to existing ones,” says Robert Blum, director of product marketing for Oclaro's photonic components.

Meanwhile JDSU demonstrated its ONT-100G test set that supports the CFP2 and CFP4 MSAs.

"Initially the [test set] applications are focused on those doing the fundamental building blocks [for the 100G CFP2] – chip vendors, optical module vendors, printed circuit board developers," says Paul Brooks, director for JDSU's high speed transport test portfolio. "We will roll out more applications within the year that cover early deployment and production."

The standards-based client-side interfaces is an attractive market for test and measurement companies. For line-side optical transmission, much of the development work is proprietary such that developing a test set to serve vendors' proprietary solutions is not feasible.

The biggest engineering challenge for the CFP2 is its adoption of high-speed 25Gbps electrical interfaces. "The CFP was based on third generation, mature 10 Gig I/O [input/output]," says Brooks. "To get to cost-effective CFP2 [modules] is a very big jump: that 2.5x faster [interface] equates to about a 6x greater difficulty in signal integrity issues, microwave techniques etc."

The company says that what has been holding up the emergence of the CFP2 module has been the 104-pin connector: "The pluggable connector is the big headache," says Brooks. "The expectation is that very soon we should get some early connectors."

The test equipment also supports developers of the higher-density CFP4 module, and other form factors such as the QSFP2.

JDSU will start shipping its CFP2 test equipment in the first quarter of 2013.

Oclaro's second-generation CFP and the CFP2 transceivers are sampling, with volume production starting in early 2013.

Finisar's CFP2 LR4 product will sample in 2012 and enter volume production in 2013.

Huawei's novel Petabit switch

The Chinese equipment maker showcased a prototype optical switch at this year's OFC/NFOEC that can scale to 10 Petabit.

"Although the numbers [400,000 lasers] appear quite staggering, they point to a need for photonic integration"

Reg Wilcox, Huawei

Huawei has demonstrated a concept Petabit Packet Cross Connect (PPXC), a switching platform to meet future metro and data centre requirements. The demonstrator is not expected to be a commercial product before 2017.

Current platforms have switching capacities of several Terabits. Yet Huawei believes a one thousand-fold increase in switching capacity will be needed. Fibre capacity will be filled to 20 and eventually 50 Terabits using higher-order modulation schemes and flexible spectrum. This will add up to a Petabit (one million Gigabits) per site, assuming 200 switched fibres at busy network exchanges.

"We are not saying we will introduce a 10 Petabit product in five years' time, although the technology is capable of that," says Reg Wilcox, vice president of network marketing and product management at Huawei. "We will size it to what we deem the market needs at that time."

Source: Huawei

Source: Huawei

The PPXC uses optical burst transmission to implement the switching. Such burst transmission uses ultra-fast switching lasers, each set to a particular wavelength in nanoseconds. Like Intune Networks’ Verisma iVX8000 optical packet switching and transport system, each wavelength is assigned to a particular destination port. As OTN traffic or packets arrive, they are assigned a wavelength before being sent to a destination port.

Huawei's switch demonstration linked two Huawei OSN8800 32-slot platforms, each with an Optical Transport Network (OTN) switching capacity of 2.56 Terabit-per-second (Tbps), to either side of the core optical switch, to implement what is known as a three-stage Clos switching matrix.

With each OSN8800, half the slots are for inter-machine trunks to the core optical switch, the middle stage of the Clos switch. "The other half [of the OSN8800] would be dedicated to whatever services you want to have: Gigabit Ethernet, 10 Gigabit Ethernet; whatever traffic you want riding over OTN," says Wilcox.

The core optical switch implements an 80x80 matrix using 80 wavelengths, each operating at 25Gbps. The 80x80 matrix is surrounded by MxM fast optical switches to implement a larger 320x320 matrix that has an 8 Terabit capacity. It is these larger matrices - 'switch planes' - that are stacked to achieve 10 Petabit. The PPXC grooms traffic starting at 1 Gigabit rates and can switch 100Gbps and even higher speed incoming wavelengths in future.

Oclaro provided Huawei with the ultra-fast lasers for the demonstrator. The laser - a digital supermode-distributed Bragg reflector (DS-DBR) - has an electro-optic tuning mechanism, says Robert Blum, director of product marketing for Oclaro's photonic component. Here current is applied to the grating to set the laser's wavelength. The resulting tuning speed is in nanoseconds although Oclaro will not say the exact switching speed specified for the switch.

Each switch plane uses 4x80 or 320, 25Gbps lasers. A 10 Petabit switch requires 400,000 (320x1250) lasers. "Although the numbers appear quite staggering, they point to a need for photonic integration," says Wilcox. Huawei recently acquired photonic integration specialist CIP Technologies.

The demonstration highlighted the PPXC switching OTN traffic but Wilcox stresses that the architecture is cell-based and can support all packet types: "We are flexible in the technology as the world evolves to all-packet.” The design is therefore also suited to large data centres to switch traffic between servers and for linking aggregation routers. "It is applicable in the data centre as a flattened [switch] architecture," says Wilcox.

Huawei claims the Petabit switch will deliver other benefits besides scalability. "Rough estimates comparing this device to OTN switches, MPLS switches and routers yields savings of greater than 60% on power, anywhere from 15-80% on footprint and at least a halving of fibre interconnect," says Wilcox.

Meanwhile Oclaro says Huawei is not the only vendor interested in the technology. "We have seen quite some interest recently in this area [of optical burst transmission]." says Oclaro's Blum. "I wouldn't be surprised if other companies make announcements in this space."

Further reading:

- OFC/ NFOEC 2012 paper: An Optical Burst Switching Fabric of Multi-Granularity for Petabit/s Multi-Chassis Switches and Routers

Oclaro-Opnext merger will create second largest optical component company

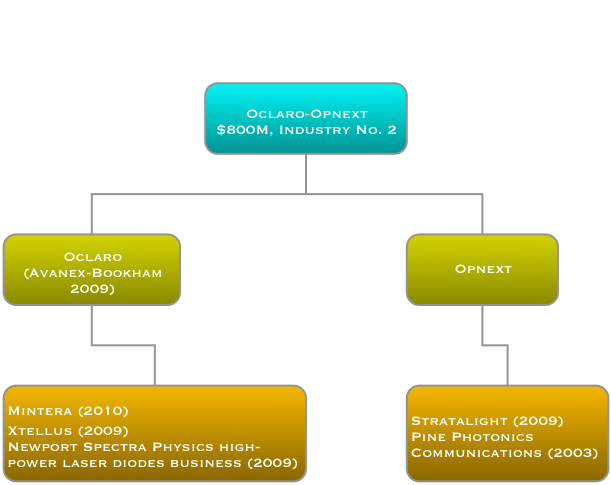

Oclaro has announced its plan to merge with Opnext. The deal, valued at US $177M, will result in Opnext's shareholders owning 42% of the combined company. The merger of the fifth and sixth largest optical component players, according to Ovum, will create a company with annual revenues of $800M, second only to Finisar. The deal is expected to be completed in the next 3-6 months.

Source: Gazettabyte

Source: Gazettabyte

Other details of the merger include:

- Combining the two companies will save between $35M-45M but will take 18 months to achieve.

- Restructuring and system integration will cost $20M-$30M.

- All five of the new company's fabs will be kept. The fabs are viewed as key assets.

- The new company will continue its use of contract manufacturers in Asia. Oclaro announced a recent deal with Venture, and that included the possibility of an Oclaro-Opnext merger.

- Oclaro's CEO, Alain Couder, will become the CEO of the new company. Harry Bosco, Opnext's CEO, will join the company's board of directors, made up of six Oclaro and four Opnext members.

- In 4Q 2011, Oclaro reported three customers, each accounting for greater than 10% sales: Fujitsu, Infinera and Ciena. Opnext reported 43% of its sales to Cisco Systems and Hitachi in the same period.

Industry scale

The motivation for the merger is to achieve industry scale, says Oclaro. "We have never been shy [of mergers and acquisitions] - we did Avanex and Bookham," says Yves LeMaitre, chief marketing officer for Oclaro. "We believe industry scale allows you to absorb certain fixed costs like fab infrastructure and the sales force." Scale also increases the absolute amount that can be invested in R&D, estimated at 12-13% of its revenues.

"It [the acquisition] is really about building a company that directly competes with Finisar," says Daryl Inniss, practice leader, components at Ovum. "It creates a stronger, vertically integrated company that starts at chips and goes all the way to the line card."

"We will be one of the most vertically integrated suppliers for 100 Gigabit coherent technology"

Mike Chan, Opnext

LightCounting believes the Oclaro-Opnext merger will be a success. Moreover, the market research firm expects further optical component M&As. Since the Oclaro-Opnext was announced, Sumitomo Electric Device Innovations has announced it will acquire Emcore's VCSEL and associated transceiver technology for $17M.

Meanwhile, Morgan Stanley Research is less positive about the merger, believing that the Opnext acquisition carries 'material risk'. It argues that the stated synergies are aggressive and that the integration of the two firms could distract Oclaro and lower its share price.

Products and technology

The deal expands Oclaro's transceiver portfolio, enhancing its offerings in telecom and strengthening its presence in datacom. It also expands the customer base: Opnext supplies Juniper, Google and H-P, new customers for Oclaro.

Common products shared by the two firms are limited, for high-end products the overlap is mainly 100 Gigabit coherent and tunable laser XFPs. LightCounting also points out that the two share some legacy SONET/SDH, WDM and Ethernet products: "Nothing that reduces competition significantly," it says in a research note.

"[With the Avanex-Bookham merger] There was a little bit of overlap in a few areas which we managed," says Oclaro's LeMaitre. "It is even easier in this case."

"We see potential, further down the road, for new very-short-reach optical interfaces"

Yves LeMaitre, Oclaro

Opnext acquired optical transmission subsystem vendor StrataLight in 2009 while Oclaro acquired Mintera in 2010. Both Oclaro and Opnext have used the expertise of the two subsystem vendors to become early market entrants of 100 Gigabit 168-pin multi-source modules.

But Oclaro makes the optical components for the modules - tunable lasers, lithium niobate modulators and integrated coherent transceivers - items that Opnext has to buy for its 100 Gig coherent module, says Ovum's Inniss: "Opnext has built decent gross margins when you consider that a lot of the optics they don't own themselves.” Oclaro's components will be used within Opnext's modules.

"We will be one of the most vertically integrated suppliers for key 100 Gigabit coherent technology moving forward," says Mike Chan, executive vice president of business development and marketing at Opnext.

Opnext stresses that it has its own programmes for integrated photonics. "We have been telling our customers that we have been working on some of these integrated photonics [for 100G coherent]," says Chan. "The StrataLight portion of Opnext also has a lot of work done, and IP created, in the coherent modem area."

Currently both companies' 100 Gigabit modules use NEL's coherent receiver DSP-ASIC. Oclaro has also made an investment in coherent chip start-up, ClariPhy. But for future coherent adaptive-rate designs, the joint company will be able to develop its own coherent chip. "We have the in-house know-how for the coherent modem chip," says Chan.

The merged company is well positioned to address client-side 100 Gigabit-ber-second (Gbps) transceivers. "Here the challenge is to achieve high density and low power [interfaces]," says Chan. Oclaro has VCSEL technology that can be used for very short reach 4x28Gbps arrays. Oclaro says it is the world's leading supplier of VCSELs for a variety of commercial applications and has now shipped over 150M units.

At OFC/NFOEC Opnext demonstrated a 1310nm LISEL (Lens-integrated Surface-Emitting distributed feedback Laser) array operating at 25-40Gbps. The surface-emitting distributed feedback (DFB) laser can also be used for the same 4x28Gbps design, says Chan. "Within the data centre 500m is the sweet-spot," says Chan. "It is not just the physical distance but the link-budget as the signal may have to go through a patch panel." The DFB can be used with multi-mode and single-mode fibre and Opnext believes it can achieve a 1km reach.

Oclaro does not rule out using its VCSEL technology to address such applications as optical engines, connecting racks and for backplanes. "We see potential, further down the road, for new very-short-reach optical interfaces into consumer, backplane, and board-to-board to really expand our addressable market," says LeMaitre

Further mergers

LightCounting argues that the 2011 floods in Thailand have added urgency to industry consolidation, with the Oclaro and Opnext merger being the first of several. Oclaro and Opnext were among the most impacted by the flood with Q4 2011 revenues being down 18% and 38%, respectively, says LightCounting.

Ovum also expects further mergers as companies strengthen their coherent and ROADM technologies.

Inniss believes ROADMs is the next area that Oclaro is likely to strengthen. Oclaro has acquired Xtellus but Ovum says the main ROADM leaders are Finisar, JDS Uniphase and CoAdna. Companies to watch include JDS Uniphase, Fujitsu Optical Components, CoAdna and Sumitomo, says Inniss.

A day after Ovum's and LightCounting's M&A comments, Sumitomo announced the acquisition of Emcore's VCSEL business unit.

100 Gigabit direct detection gains wider backing

More vendors are coming to market with 100 Gigabit direct detection products for metro and private networks.

The emergence of a second de-facto 100 Gigabit standard, a complement to 100 Gigabit coherent, has gained credence with 4x28 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) direct detection announcements from Finisar and Oclaro, as well as backing from system vendor, ECI Telecom.

"We believe that in some cases operators will prefer to go with this technology instead of coherent"

Shai Stein, CTO, ECI Telecom

ECI Telecom and chip vendor MultiPhy announced at OFC/NFOEC that they have been collaborating to develop a 168-pin MSA, 5x7-inch 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) direct detection module. Finisar and Oclaro used the show held in Los Angeles to announce their market entry with 100Gbps direct detection CFP pluggable optical modules.

Late last year ADVA Optical Networking announced the industry's first 100Gbps direct detection product. At the same time, MultiPhy detailed its MP1100Q receiver chip designed for 100Gbps direct detection.

According to ECI, by having the 168-pin MSA interface, one line card can support a 100Gbps coherent transponder or the 100Gbps direct detection. "This is important as it enables us to fit the technology and price to the needs of end customers," says Shai Stern, CTO of ECI Telecom.

100 Gigabit transmission

Coherent technology has become the de-facto standard for 100Gbps long-haul transmission. Using dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM), system vendors can achieve 1,500km and greater reaches using a 50GHz channel.

But coherent designs are relatively costly and 100Gbps direct detection offers a cost-conscious alternative for metro networks and for linking data centres, achieving a reach of up to 800km.

"It [100 Gig direct detection] provides needed performance at an attractive cost, in particular when you are looking at private optical networks," says Per Hansen, vice president of product marketing, optical networks solutions at Oclaro.

Such networks need not be owned by private enterprises, they can belong to operators, says Hansen, but they are typically simple point-to-point connections or 3- to 4-node rings serving enterprises. "Bonding adjacent [4x28Gbps] wavelengths to create a 100Gbps channel that connects efficiently to your [IP] router is very attractive in such networks," says Hansen.

For more complex mesh metro networks, coherent is more attractive. "Simply because of the spectral resources being taken up through the mesh [with 4x28Gbps], and the operational aspect of routeing that," says Hansen.

ECI Telecom says that it has yet to decide whether it will adopt 100Gbps direct detection. But it does see a role for the technology in the metro since the 100Gbps technology works well alongside networks with 10 and 40 Gigabit on-off keying (OOK) channels. "We believe that in some cases operators will prefer to go with this technology instead of coherent," says Stein.

Some operators have chosen to deploy coherent over new overlay networks, to avoid the non-linear transmission effects that result from mixing old and new technologies on the one network. "With this technology, operators can stay with their existing networks yet benefit from 100 Gig high capacity links," says Stein.

Finisar says 100Gbps direct detection is also suited to low-latency applications. "The fact that it is not coherent means it doesn't include a DSP chip, enabling it to be used for low latency applications," says Rafik Ward, vice president of marketing at Finisar.

Implementation

The announced 100Gbps direct detection designs all use 4x28Gbps channels and optical duo-binary (ODB) modulation, although MultiPhy also promotes an 80km point-to-point OOK version (see Table).

Source: Gazettabyte

Source: Gazettabyte

The module input is a 10x10Gbps electrical interface: a CFP interface or the 168-pin line side MSA. A 'gearbox' IC is used to translate between the 10x10Gbps electrical interface and the four 28Gbps channels feeding the optics.

"There are a few suppliers that are offering that [gearbox IC]," says Robert Blum, director of product marketing for Oclaro's photonic components. AppliedMicro recently announced a duplex multiplexer-demultiplexer IC.

MultiPhy's receiver chip has a digital signal processor (DSP) that implements the maximum likelihood sequence estimation (MLSE) algorithm, which is says enables 10 Gig opto-electronics to be used for each channel. The result is a 100Gbps module based on the cost of 4x10Gbps optics. However, over-driving the 10Gbps opto-electronics creates inter-symbol interference, where the energy of a transmitted bit leaks into neighbouring signals. MultiPhy's DSP using MLSE counters the inter-symbol interference.

100G direct detection module showing MultiPhy's MP1100Q chip. Source: MultiPhy

100G direct detection module showing MultiPhy's MP1100Q chip. Source: MultiPhy

Oclaro and Finisar claim that using ODB alone enables the use of lower-speed opto-electronics. "This is irrespective of whether you use MLSE or hard decision," says Blum. "The advantage of using optical duo-binary modulation is that you can use 10G-type optics."

Finisar's Ward points out that by using ODB, the 100Gbps direct-detection module avoids the price/ power penalty associated with a receiver DSP running MLSE to compensate for sub-optimal optical components.

Oclaro, however, has not ruled out using MLSE in future. The company endorsed MultiPhy's MLSE device when the product was first announced but its first 100G transceiver is not using the IC.

Finisar and Oclaro's modules require 200GHz to transmit the 100Gbps signal: 4x50GHz channels, each carrying the 28Gbps signal. "This architecture will enable 2.5x the spectral efficiency of tunable XFPs," says Ward. Using XFPs, ten would be needed for a 100Gbps throughput, each channel requiring 50GHz or 500GHz in total.

MultiPhy claims that it can implement the 100Gbps in a 100GHz channel, 5x the efficiency but still twice the spectrum used for 100Gbps coherent.

Finisar demonstrated its 100Gbps CFP module with SpectraWave, a 1 rack unit (1U) DWDM transport chassis, at OFC/NFOEC. "It provides all the things you need in line to enable a metro Ethernet link: an optical multiplexer and demultiplexer, amplification and dispersion compensation," says Ward. Up to four CFPs can be plugged into the SpectraWave unit.

Operator interest

In a recent survey published by Infonetics Research, operators had yet to show interest in 100Gbps direct detection. Infonetics attributed the finding to the technology still being unavailable and that operators hadn't yet assessed its merits.

"Operators are aware of this technology," says ECI's Stein. "It is true they are waiting to get a proof-of-concept and to test it in their networks and see the value they can get.

"That is why ECI has not yet decided to go for a generally-available product: we will deliver to potential customers, get their feedback and then take a decision regarding a commercial product," says Stein.

However MultiPhy claims that this is the first technology that enables 100Gbps in a pluggable module to achieve a reach beyond 40km. That fact coupled with the technology's unmatched cost-performance is what is getting the interest. "Every time you show a potential user some way they can save on cost, they are interested," says Neal Neslusan, vice president of sales and marketing at MultiPhy.

Direct detection roadmap

Recent announcements by Cisco Systems, Ciena, Alcatel-Lucent and Huawei highlight how the system vendors will use advanced modulation and super-channels to evolve coherent to speeds beyond 100Gbps. Does direct detection have a similar roadmap?

"I don't think that this on-off keying technology is coming instead of coherent," says Stein. "Once we move to super-channel and the spectral densities it can achieve, coherent technology is a must and will be used." But for 40Gbps and 100Gbps, what ECI calls intermediate rates, direct detection extends the life of OOK and existing network infrastructure.

ECI and MultiPhy are members of the Tera Santa Consortium developing 1 Terabit coherent technology, and MultiPhy stresses that as well as its direct detection DSP chips, it is also developing coherent ICs.

Further reading: 100 Gigabit: The coming metro opportunity

2012: The year of 100 Gigabit transponders

“The world is moving to coherent, there is no question about that”

“The world is moving to coherent, there is no question about that”

Per Hansen, Oclaro

The 100Gbps module expands the company's coherent offerings. Oclaro is already shipping a 40Gbps coherent module. “The world is moving to coherent, there is no question about that,” says Per Hansen, vice president of product marketing, optical networks solutions at Oclaro.

Why is this significant?

Having a selection of 100Gbps long-haul optical modules will aid the uptake of high-capacity links in the network core. Opnext announced in September its OTM-100 100Gbps coherent optical module, in production from April 2012. And at least one other module maker has worked with ADVA Optical Networking to make its 100Gbps module, a non-coherent design.

The 100Gbps coherent optical modules will enable system vendors without their own technology to enter the marketplace. It also presents those system vendors with their own 100Gbps technology - the likes of Alcatel-Lucent, Ciena, Cisco and Huawei - with a dilemma: do they continue to evolve their products or embrace optical modules?

“These system vendors have developed [100Gbps] in-house to have a strategic differentiator," says Hansen. "But with lower volumes you have a higher cost.” The advent of 100Gbps modules diminishes the strategic advantage of in-house technology while enabling system vendors to benefit from cheaper, more broadly available modules, he says.

What has been done

Oclaro is still developing the MI 8000XM module and has yet to reveal the reach performance of the module: “We want to do many more tests before we share,” says Hansen. The module will meet the Optical Internetworking Forum's (OIF) 100Gbps module maximum power consumption limit of 80W, he says.

The OIF 100 Gigabit module architecture

The OIF 100 Gigabit module architecture

The NEL DSP chip is the same device that Opnext is using for its 100Gbps module. “A partnership agreement and sourcing arrangement with NEL allows us to come to market with what we think is a very good product at the right time,” says Hansen.

The DSP uses soft-decision forward error correction. Opnext has said this adds 2-3dB to the optical performance to achieve a reach of 1500-1600km before regeneration.

In 2010 Oclaro announced it had invested US $7.5 million in Clariphy Communications as part of the chip company's development of its 100Gbps coherent receiver chip, the CL10010. As part of the agreement, Oclaro will get a degree of exclusivity as a module supplier (at least one other module maker will also benefit).

ClariPhy has said that while it will not be first to market with a 100Gbps ASIC, the CL10010 will be a 28nm CMOS second-generation chip design. To be able to enter the market with a 100Gbps module next year, Oclaro adopted NEL's design which exists now.

Next

Hansen says that the MI 8000XM, which uses a lithium niobate modulator, is designed to achieve maximum reach and optical performance. But future 100Gbps modules will be developed that may use other modulator technologies and be optimised in terms of power or size.

Hansen is also in no doubt that the next speed hike after 100Gbps will be 400Gbps. Like 100Gbps, there will be some early-adopter operators that embrace the technology one or two years before the consensus.

Such a development is still several years away, however, since an industry standard for 400Gbps must be developed which is only expected in 2014 only.

Oclaro points its laser diodes at new markets

“To succeed in any market ... you need to be the best at something, to have that sustainable differentiator”

Yves LeMaitre, Oclaro

Now LeMaitre is executive vice president at Oclaro, managing the company’s advanced photonics solutions (APS) arm. The APS division is tasked with developing non-telecom opportunities based on Oclaro’s high-power laser diode portfolio, and accounts for 10%-15% of the company’s revenues.

“The goal is not to create a separate business,” says LeMaitre. “Our goal is to use the infrastructure and the technologies we have, find those niche markets that need these technologies and grow off them.”

Recently Oclaro opened a design centre in Tucson, Arizona that adds packing expertise to its existing high-power laser diode chip business. The company bolstered its laser diode product line in June 2009 when Oclaro gained the Newport Spectra Physics division in a business swap. “We became the largest merchant vendor for high-power laser diodes,” says LeMaitre.

The products include single laser chips, laser arrays and stacked arrays that deliver hundred of watts of output power. “We had all that fundamental chip technology,” says LeMaitre. “What we have been less good at is packaging those chips - managing the thermals as well as coupling that raw chip output power into fibre.”

The new design centre is focussed on packaging which typically must be tailored for each product.

Laser diodes

There are three laser types that use laser diodes, either directly or as ‘pumps’:

- Solid-state laser, known as diode-pumped solid-state (DPSS) lasers.

- Fibre laser, where the fibre is the medium that amplifies light.

- Direct diode laser - here the semiconductor diode itself generates the light.

All three types use laser diodes that operate in the 800-980nm range. Oclaro has much experience in gallium arsenide pump-diode designs for telecom that operate at 920nm wavelengths and above.

Laser diode designs for non-telecom applications are also gallium arsenide-based but operate at 800nm and above. They are also scaled-up designs, says LeMaitre: “If you can get 1W on a single mode fibre for telecom, you can get 10W on a multi-mode fibre.” Combining the lasers in an array allows 100-200W outputs. And by stacking the arrays while inserting cooling between the layers, several hundreds of watts of output power are possible.

The lasers are typically sold as packaged and cooled designs, rather than as raw chips. The laser beam can be collimated to precisely deliver the light, or the beam may be coupled when fibre is the preferred delivery medium.

“The laser beam is used to heat, to weld, to burn, to mark and to engrave,” says LeMaitre. “That beam may be coming directly from the laser [diode], or from another medium that is pumped by the laser [diode].” Such designs require specialist packaging, says LeMaitre, and this is what Oclaro secured when it acquired the Spectra Physics division.

Applications

Laser diodes are used in four main markets which Oclaro values at US$800 million a year.

One is the mature, industrial market. Here lasers are used for manufacturing tasks such as metal welding and metal cutting, marking and welding of plastics, and scribing semiconductor wafers.

Another is high-quality printing where the lasers are used to mark large printing plates. This, says LeMaitre, is a small specialist market.

Health care is a growing market for lasers which are used for surgery, although the largest segment is now skin and hair treatment.

The final main market is consumer where vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers (VCSELs) are used. The VCSELs have output powers in the tens or hundreds of milliwatts only and are used in computer mouse interfaces and for cursor navigation in smartphones.

“These are simple applications that use lasers because they provide reliable, high-quality optical control of the device,” says LeMaitre. “We are talking tens of millions of [VCSEL] devices [a year] that we are shipping right now for these types of applications.”

Oclaro is a supplier of VCSELs for Light Peak, Intel’s high-speed optical cable technology to link electronic devices. “There will be adoptions of the initial Light Peak starting the end of this year or early next year, and we are starting to ramp up production for that,” says LeMaitre. “In the meantime, there are many alternative [designs] happening – the market is extremely active – and we are talking to a lot of players.” Oclaro sells the laser chips for such interface designs; it does not sell optical engines or the cables.

Is Oclaro pursuing optical engines for datacom applications, linking large switch and IP router systems? “We are actively looking at that but we haven’t made any public announcements,” he says.

Market status

LeMaitre has been at Oclaro since 2008 when Avanex merged with Bookham (to become Oclaro). Before that, he was CEO at optical component start-up, LightConnect.

How does the industry now compare with that of a decade ago?

“At that time [of the downturn] the feeling was that it was going to be tough for maybe a year or two but that by 2002 or 2003 the market would be back to normal,” says LeMaitre. “Certainly no-one expected the downturn would last five years.” Since then, nearly all of the start-ups have been acquired or have exited; Oclaro itself is the result of the merger of some 15 companies.

“People were talking about the need for consolidation, well, it has happened,” he says. Oclaro’s main market – optical components for metro and long haul transmission – now has some four main players. “The consolidation has allowed these companies, including Oclaro, to reach a level of profitability which has not been possible until the last two years,” says LeMaitre.

Demand for bandwidth has continued even with the recent economic downturn, and this has helped the financial performance of the optical component companies.

“The need for bandwidth has still sustained some reasonable level of investment even in the dark times,” he says. “The market is not as sexy as it was in those [boom] days but it is much more healthy; a sign of the industry maturing.”

Industry maturity also brings corporate stability which LeMaitre says provides a healthy backdrop when developing new business opportunities.

The industrial, healthcare and printing markets require greater customisation than optical components for telecom, he says, whereas the consumer market is the opposite, being characterised by vastly greater unit volumes.

“To succeed in any market – this is true for this market and for the telecom market – you need to be the best at something, to have that sustainable differentiator,” says LeMaitre. For Oclaro, its differentiator is its semiconductor laser chip expertise. “If you don’t have a sustainable differentiator, it just doesn’t work.”

Oclaro: R&D key for growth

“We didn’t sell to Intel,” explains Alain Couder, the boss of Oclaro. “Intel looked for a fab[rication plant] that has good VCSEL technology and that could scale and they found us.”

Couder was talking about how Oclaro became a supplier of vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers (VCSELs) for Intel’s Light Peak optical cable interface technology. VCSELs are part of Oclaro’s Advanced Photonics Solutions, a division addressing non-telecom markets accounting for between 10 and 15 percent of the company’s revenues.

“I believe very clearly that if a component is available on the market, even if you are a module builder, you are much better off selling to your competition rather than having others do so.”

Alain Couder, Oclaro

Couder joined Bookham in August 2007 and oversaw its merger with Avanex in 2009, resulting in Oclaro. The restructuring has been intensive, with unprofitable product lines discontinued, facilities closed and jobs cut.

“During all this restructuring we never cut R&D,” says Couder. “We have been able to increase our [R&D] people as a third are now in Asia,” he says. “Even in Europe – the UK and Italy – [the cost of] engineers are two-thirds that of the US or Japan.” Indeed Couder says the company is increasing R&D spending from 11 to 13 percent of its revenues. “With growth that we have had - on average 10 percent quarter-on-quarter - we are hiring R&D staff as quickly as we can.”

Vertical integration

Oclaro’s CEO believes being a vertically integrated company – making optical components and modules – is an important differentiator. By designing optical components, Oclaro can drive down cost and tailor designs that it can sell to system vendors and module makers. Such a capability also benefits Oclaro’s own modules.

Couder stresses that there is no conflict of interest selling optical components to module firms that Oclaro competes with. “I believe very clearly that if a component is available on the market, even if you are a module builder, you are much better off selling to your competition rather than having others do so.”

Oclaro supplies components to the likes of Finisar and Opnext, he says, and it has not stopped Oclaro being successful with its 10 Gigabit small form factor (SFF) transponder. Being vertically integrated benefits Oclaro’s modules, growing its market share, says Couder: “Like this year with the SFF and as we expect to be doing next year with our tunable XFPs.” Selling 10 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) modules also means telecom vendors are buying more modules and less optical components.

“We are going to pursue the same strategy at 40 and 100 Gig,” says Couder. System vendors such as Alcatel-Lucent and Ciena may design their line side optics but as designs become cheaper and performance optimised, Oclaro will be better able to compete. “Our own module solution, or at least our gold box, becomes more competitive than their own design,” he says.

Another important technology aiding vertical integration is photonic integration. “As you put more functions on one chip you get better value,” says Couder. Oclaro has integrated a laser and modulator in indium phosphide that replaces two optical functions that until now have been sold separately. The integrated design takes a third less space yet Oclaro can sell it at a better margin.

40 and 100Gbps markets

Oclaro supplies optical components for 40Gbps differential phase-shift keying (DPSK) modulation and offers its own components and module for 40Gbps differential quadrature phase-shift keying (DQPSK) for the metro/ regional market. Indeed Oclaro is a DQPSK reference design provider for Huawei, the Chinese system vendor with more than 30 percent market share at 40Gbps.

Oclaro is also developing a 100Gbps coherent detection module based on polarisation multiplexing quadrature phase-shift keying (PM-QPSK) modulation, the industry defacto standard. “We think for the very long haul there might be a small market for PM-QPSK at 40Gbps but most of the coherent modulation will be at 100Gbps,” says Couder. “But at the [40Gbps] module level we are continue to be focused on DQPSK.”

Given the recent flurry of 100Gbps coherent announcements, is Oclaro seeing signs of 40Gbps being squeezed and becoming a stop-gap market? “

The only thing I can tell you is that I got this morning again an escalation from one top customer because we can’t supply optical components fast enough for their 40Gbps deployment,” says Couder. “This is all the noise around coherent - 100Gbps will be deployed but even at 100Gbps people are looking at shorter distance solution that are cheaper than coherent. I have not seen any slowing down of 40Gbps.”

He expects 40Gbps to mirror the 10Gbps market which is set for healthy sales over the coming two to three years. Prices continue to come down at 10Gbps and the same is happening at 40Gbps. Ten gigabit modules range from $1,500 to $1,800 depending on their specification while 40Gbps modules are around $6,000. Meanwhile 100Gbps modules will at least be twice the cost of 40Gbps. “There are many sub-networks deployed with [40Gbps] DPSK and DQPSK and I don’t see how operators are going to change everything to 100Gbps on those sub-networks,” says Couder.

Clariphy investment

Oclaro recently announced it had invested US $7.5 million in chip firm Clariphy Communications. Oclaro will develop with Clariphy coherent receiver chip technology for 100Gbps optical transmission and co-market Clariphy's ICs. “We will train our sales force on Clariphy products so we can present to our customers a combination of optical and high-speed components,” says Couder. “We will go as far as giving reference designs.”

In addition to the emerging 100Gbps, there will be marketing of Oclaro’s tunable XFP+ with Clariphy’s ICs and also co-marketing of 40Gbps technology, for example Oclaro’s balanced receiver working with Clariphy’s 40Gbps coherent IC.

Choosing Clariphy was straightforward, says Couder. There were only three “serious” component suppliers: CoreOptics, Opnext and Clariphy. Cisco Systems has announced its plan to acquire CoreOptics while Opnext is a competitor. But Couder stresses that the investment in Clariphy also follows two years of working together.

Couder agrees that the 100Gbps coherent application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) market is heating up and that there are many potential entrants. That said, he is unaware of many other players that can present a combination of optical components and the ASIC. He also thinks Clariphy has an elegant ASIC that combines the analogue and digital circuitry on one chip.

Meanwhile the Cisco acquisition of CoreOptics is good news for Oclaro. “It took one of the suppliers out of the market; one that was well positioned.” Oclaro is also a supplier of optical components to CoreOptics and to Cisco. “We expect to continue to supply and for us this will be a plus as it [Cisco/ CoreOptics’s solutions] will scale much faster,” he says.

Growth

In other product areas, Oclaro is focussing on its tunable XFP after first launching a extended XFP tunable laser design. “We’re sampling this quarter the regular tunable XFP,” says Couder. “We have been selling a few extended XFPs – the X2 – but the big market is the tunable XFP.”

Oclaro has two offerings – a replacement for the 80km fixed-wavelength XFP that will ship at the end of the end of the year, and a higher specification tunable XFP aimed at replacing 10Gbps 300-pin tunable modules. Couder admits JDS Uniphase dominates tunable XFPs having been first to market. “But we are coming very close behind and what customers are telling me is our performance is better.”

The market for optical amplifiers is also experiencing growth. “We are back to the level before the downturn, back to the level of September 2008,” he says.

The drivers? More optical networking links in the core are being deployed to accommodate growth in wireless traffic, video servers and FTTx, he says. Oclaro is also starting to see demand for lower latency networks. “Some financial applications are looking for lower latency,” he says. “They need gain blocks for 40Gig now and 100Gig tomorrow.” Another telecom segment Oclaro claims it is doing well is tunable optical dispersion compensation modules.

Outside telecom Oclaro's next generation pump products are finding use in cosmetic products while its VCSELs are being used for a future disk drive design. Then there is Light Peak, Intel’s high-speed optical cable technology to link electronic devices. “Intel’s Light Peak will be big; when exactly it will deployed I'm not in a position to say but it will be calendar year 2011.”