Q&A with Rafik Ward - Part 1

"This is probably the strongest growth we have seen since the last bubble of 1999-2000." Rafik Ward, Finisar

"This is probably the strongest growth we have seen since the last bubble of 1999-2000." Rafik Ward, Finisar

Q: How would you summarise the current state of the industry?

A: It’s a pretty fun time to be in the optical component business, and it’s some time since we last said that.

We are at an interesting inflexion point. In the past few years there has been a lot of emphasis on the migration from 1 to 2.5 Gig to 10 Gig. The [pluggable module] form factors for these speeds have been known, and involved executing on SFP, SFP+ and XFPs.

But in the last year there has been a significant breakthrough; now a lot of the discussion with customers are around 40 and 100 Gig, around form factors like QSFP and CFP - new form factors we haven’t discussed before, around new ways to handle data traffic at these data rates, and new schemes like coherent modulation.

It’s a very exciting time. Every new jump is challenging but this jump is particularly challenging in terms of what it takes to develop some of these modules.

From a business perspective, certainly at Finisar, this is probably the strongest growth we have seen since the last bubble of 1999-2000. It’s not equal to what it was then and I don’t think any of us believes it will be. But certainly the last five quarters has been the strongest growth we’ve seen in a decade.

What is this growth due to?

There are several factors.

There was a significant reduction in spending at the end of 2008 and part of 2009 where end users did not keep up with their networking demands. Due to the global financial crisis, they [service providers] significantly cut capex so some catch-up has been occurring. Keep in mind that during the global financial crisis, based on every metric we’ve seen, the rate of bandwidth growth has been unfazed.

From a Finisar perspective, we are well positioned in several markets. The WSS [wavelength-selective switch] ROADM market has been growing at a steady clip while other markets are growing quite significantly – at 10 Gig, 40 Gig and even now 100 Gig. The last point is that, based on all the metrics we’ve seen, we are picking up market share.

Your job title is very clear but can you explain what you do?

I love my job because no two days are the same. I come in and have certain things I expect to happen and get done yet it rarely shapes out how I envisaged it.

There are really three elements to my job. Product management is the significant majority of where I focus my efforts. It’s a broad role – we are very focussed on the products and on the core business to win market share. There is a pretty heavy execution focus in product management but there is also a strategic element as well.

The second element of my job is what we call strategic marketing. We spend time understanding new, potential markets where we as Finisar can use our core competencies, and a lot of the things we’ve built, to go after. This is not in line with existing markets but adjacent ones: Are there opportunities for optical transceivers in things like military and consumer applications?

One of the things I’m convinced of is that, as the price of optical components continues to come down, new markets will emerge. Some of those markets we may not even know today, and that is what we are finding. That’s a pretty interesting part of my job but candidly I spend quite a bit less time on it [strategic marketing] than product management.

The third area is corporate communications: talking to media and analysts, press releases, the website and blog, and trade shows.

"40Gbps DPSK and DQPSK compete with each other, while for 40 Gig coherent its biggest competitor isn’t DPSK and DQPSK but 100 Gig."

Some questions on markets and technology developments.

Is it becoming clearer how the various 40Gbps line side optics – DPSK, DQPSK and coherent – are going to play out?

The situation is becoming clearer but that doesn’t mean it is easier to explain.

The market is composed of customers and end users that will use all of the above modulation formats. When we talk to customers, every one has picked one, two or sometimes all three modulation formats. It is very hard to point to any trend in terms of picks, it is more on a case-by-case basis. Customers are, like us at the component level, very passionate about the modulation format that they have chosen and will have a variety of very good reasons why a particular modulation format makes sense.

Unlike certain markets where you see a level of convergence, I don’t think that there will be true convergence at 40 Gbps. Coherent – DP-QPSK - is a very powerful technology but the biggest challenge 40 Gig has with DP-QPSK is that you have the same modulation format at 100 Gig.

The more I look at the market, 40Gbps DPSK and DQPSK compete with each other, while for 40 Gig coherent its biggest competitor isn’t DPSK and DQPSK but 100 Gig.

Finisar has been quiet about its 100 Gig line side plans, what is its position?

We view these markets - 40 and 100 Gig line side – as potentially very large markets at the optical component level. Despite that fact that there are some customers that are doing vertical integrated solutions, we still see these markets as large ones. It would be foolish for us not to look at these markets very carefully. That is probably all I would say on the topic right now.

"Photonic integration is important and it becomes even more important as data rates increase."

Finisar has come out with an ‘optical engine’, a [240Gbps] parallel optics product. Why now?

This is a very exciting part of our business. We’ve been looking for some time at the future challenges we expect to see in networking equipment. If you look at fibre optics today, they are used on the front panel of equipment. Typically it is pluggable optics, sometimes it is fixed, but the intent is that the optics is the interface that brings data into and out of a chassis.

People have been using parallel optics within chassis – for backplane and other applications – but it has been niche. The reason it’s niche is that the need hasn’t been compelling for intra-chassis applications. We believe that need will change in the next decade. Parallel optics intra-chassis will be needed just to be able to drive the amount of bandwidth required from one printed circuit board to another or even from one chip to another.

The applications driving this right now are the very largest supercomputers and the very largest core routers. So it is a market focussed on the extreme high-end but what is the extreme high-end today will be mainstream a few years from now. You will see these things in mainstream servers, routers and switches etc.

Photonic integration – what’s happening here?

Photonic integration is something that the industry has been working on for several years in different forms; it continues to chug on in the background but that is not to understate its importance.

For vendors like Finisar, photonic integration is important and it becomes even more important as data rates increase. What we are seeing is that a lot of emerging standards are based around multiple lasers within a module. Examples are the 40GBASE-LR4 and the 100GBASE-LR4 (10km reach) standards, where you need four lasers and four photo-detectors and the corresponding mux-demux optics to make that work.

The higher the number of lasers required inside a given module, and the more complexity you see, the more room you have to cost-reduce with photonic integration.

Google and the optical component industry

According to a report by Pauline Rigby, Google wants something in between two existing IEEE interface standards. The 100GBase-SR10, which has 10 parallel channels and a 125m span, has too short a reach for Google.

“What is good for an 800-pound gorilla is not necessarily good for the industry. It [Google] should have been at the table when the IEEE was working on the standard."

“What is good for an 800-pound gorilla is not necessarily good for the industry. It [Google] should have been at the table when the IEEE was working on the standard."

Daryl Inniss, practice leader, components, Ovum

The second interface, the 100GBase-LR4, uses four channels that are multiplexed onto a single fibre and has a 10km reach. The issue here is that Google doesn’t need a 10km reach and while a single fibre is better than the multi-mode fibre based SR10, the interface is costly with its “gearbox” IC that translates between 10 lanes of 10Gbps and four lanes each at 25Gbps. Both IEEE interfaces are also implemented using a CFP form factor which is bulky.

What Google wants

Google wants optical component vendors to develop a new 100 Gigabit Ethernet multi-source agreement (MSA) that is based on a single-mode interface with a 2km reach, reports Rigby. Such a design would use a ten-channel laser array whose output is multiplexed onto a fibre, a similar laser array-multiplexer arrangement that has already been developed by Santur. Using such a part, the new interface could be developed quickly and cheaply, says Google.

The proposed interface clearly has merits and Google, an important force with an appetite for optics, makes some valid points. But the industry is developing 4x25Gbps interfaces and while such interfaces may be challenging, no-one doubts they will come.

Google’s next moves

Google has a history of being contrarian if it believes it best serves its business. The way the internet giant designs data centres is one example, using massive numbers of cheap servers arranged in a fault-tolerant architecture.

But there is only so much it can do in-house and developing a new optical interface will require help from optical component players.

Google has the financial muscle to hire an optical component firm to engineer and manufacture a custom interface. A recent example of such a partnership is IBM's work with Avago Technologies to develop board-level optics – or an optical engine – for use within IBM’s POWER7 supercomputer systems.

According to Karen Liu, vice president, components and video technologies at market research firm Ovum, once such an interface is developed, Google could allow others to buy it to help reduce its price. “Remember the Lucent form factor which became a de facto standard but wasn’t originally intended to be?” says Liu. “This approach could work.”

Taking a longer term view, Google could also invest in optical component start-ups. The return may take years and as the experience of the last decade has shown, optical components is a risky business. But Google could encourage a supply of novel, leading-edge technologies over the next decade.

The optical component industry is right to push back with regard Google’s request for a new 100 Gigabit Ethernet MSA, as Finisar has done. While Google may be an important player that can drive interface requirements, many players have helped frame the IEEE 100Gbps Ethernet standards work. In the last decade the optical industry has also seen other giant firms try to drive the industry only to eventually exit.

“The industry needs to move on,” says Daryl Inniss, practice leader, components at Ovum. “What is good for an 800-pound gorilla is not necessarily good for the industry.” Inniss also suggests a simple and effective way Google could have influenced the 100 Gigabit Ethernet MSA work: “It [Google] should have been at the table when the IEEE was working on the standard."

Differentiation in a market that demands sameness

At first sight, optical transceiver vendors have little scope for product differentiation. Modules are defined through a multi-source agreement (MSA) and used to transport specified protocols over predefined distances.

“Their attitude is let the big guys kill themselves at 40 and 100 Gig while they beat down costs"

Vladimir Kozlov, LightCounting

“I don’t think differentiation matters so much in this industry,” says Daryl Inniss, practice leader components at Ovum. “Over time eventually someone always comes in; end customers constantly demand multiple suppliers.”

It is a view confirmed by Luc Ceuppens, senior director of marketing, high-end systems business unit at Juniper Networks. “We do look at the different vendors’ products - which one gives the lowest power consumption,” he says. “But overall there is very little difference.”

For vendors, developing transceivers is time-consuming and costly yet with no guarantee of a return. The very nature of pluggables means one vendor’s product can easily be swapped with a cheaper transceiver from a competitor.

Being a vendor defining the MSA is one way to steal a march as it results in a time-to-market advantage. There have even been cases where non-founder companies have been denied sight of an MSA’s specification, ensuring they can never compete, says Inniss: “If you are part of an MSA, you are very definitely at an advantage.”

Rafik Ward, vice president of marketing at Finisar, cites other examples where companies have an advantage.

One is Fibre Channel where new data rates require high-speed vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers (VCSELs) which only a few companies have.

Another is 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) for long-haul transmission which requires companies with deep pockets to meet the steep development costs. “One hundred Gigabit is a very expensive proposition whereas with the 40 Gigabit Ethernet LR4 (10km) standard, existing off-the-shelf 10Gbps technology can be used,” says Ward.

"One hundred Gigabit is a very expensive proposition"

"One hundred Gigabit is a very expensive proposition"

Rafik Ward, Finisar

Ovum’s Inniss highlights how optical access is set to impact wide area networking (WAN). The optical transceivers for passive optical networking (PON) are using such high-end components as distributed feedback (DFB) lasers and avalanche photo-detectors (APDs), traditionally components for the WAN. Yet with the higher volumes of PON, the cost of WAN optics will come down.

“With Gigabit Ethernet the price declines by 20% each time volumes double,” says Inniss. “For PON transceivers the decline is 40%.” As 10Gbps PON optics start to be deployed, the price benefit will migrate up to the SONET/ Ethernet/ WAN world, he says. Accordingly, those transceiver players that make and use their own components, and are active in PON and WAN, will most benefit.

“Differentiation is hard but possible,” says Vladimir Kozlov, CEO of optical transceiver market research firm, LightCounting. Active optical cables (AOCs) have been an area of innovation partly because vendors have freedom to design the optics that are enclosed within the cabling, he says.

AOCs, Fibre Channel and 100Gbps are all examples where technology is a differentiator, says Kozlov, but business strategy is another lever to be exploited.

On a recent visit to China, Kozlov spoke to ten local vendors. “They have jumped into the transceiver market and think a 20% margin is huge whereas in the US it is seen as nothing.”

The vendors differentiate themselves by supplying transceivers directly to the equipment vendors’ end customers. “They [the Chinese vendors] are finding ways in a business environment; nothing new here in technology, nothing new in manufacturing,” says Kozlov.

He cites one firm that fully populated with transceivers a US telecom system vendor’s installation in Malaysia. “Doing this in the US is harder but then the US is one market in a big world,” says Kozlov.

Offshore manufacturing is no longer a differentiator. One large Chinese transceiver maker bemoaned that everyone now has manufacturing in China. As a result its focus has turned to tackling overheads: trimming costs and reducing R&D.

“Their attitude is let the big guys kill themselves at 40 and 100 Gig while they beat down costs by slashing Ph.Ds, optimising equipment and improving yields,” says Kozlov. “Is it a winning approach long term? No, but short-term quite possibly.”

Active optical cable: market drivers

CIR’s report key findings

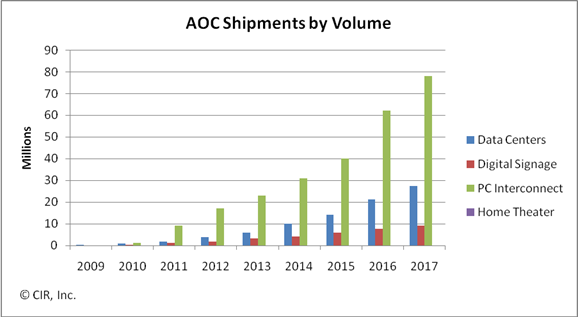

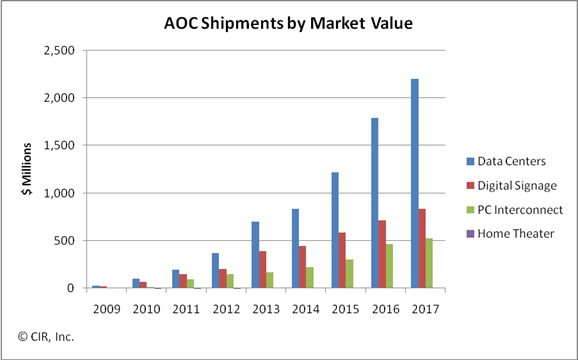

The global market for active optical cable (AOC) is forecast to grow to US $1.5bn by 2014, with the linking of datacenter equipment being the largest single market valued at $835m. Other markets for the cabling technology include digital signage, PC interconnect and home theatre.

CIR’s report entitled Active Optical Cabling: A Technology Assessment and Market Forecast notes how AOC emerged with a jolt. Two years on and the technology is now a permanent fixture that will continue to nimbly address application as they appear. This explains why CIR views AOC as an opportunistic and tactical interconnect technology.

AOC: "Opportunistic and tactical"

Loring Wirbel

What is active optical cable?

An AOC converts an electrical interface to optical for transmission across a cable before being restored to the electrical domain. Optics are embedded as part of the cabling connectors with AOC vendors using proprietary designs. Being self-contained, AOCs have the opportunity to become a retail sale at electronics speciality stores.

A common interface for AOC is the QSFP but there are AOC products that use proprietary interfaces. Indeed the same interface need not be used at each end of the cable. Loring Wirbel, author of the CIR AOC report, mentions a MergeOptics’ design that uses a 12-channel CXP interface at one end and three 4-channel QSFP interfaces at the other. “If it gets traction, everyone will want to do it,” he says.

Origins

AOC products were launched by several vendors in 2007. Start-up Luxtera saw it as an ideal entry market for its silicon photonics technology; Finisar came out with a 10Gbps serial design; while Zarlink identified AOC as a primary market opportunity, says Wirbel.

Application markets

AOC is the latest technology targeting equipment interconnect in the data centre. Typical distances linking equipment range from 10 to 100m; 10m is where 10Gbps copper cabling starts to run out of steam while 100m and above are largely tackled by structured cabling.

“Once you get beyond 100 meters, the only AOC applications I see are outdoor signage and maybe a data centre connecting to satellite operations on a campus,” says Wirbel.

AOC is used to connect servers and storage equipment using either Infiniband or Ethernet. “Keep in mind it is not so much corporate data centres as huge dedicated data centre builds from a Google or a Facebook,” says Wirbel.

AOC’s merits include its extended reach and light weight compared to copper. Servers can require metal plates to support the sheer weight of copper cabling. The technology also competes with optical pluggable transceivers and here the battleground is cost, with active optical cabling including end transceivers and the cable all-in-one.

To date AOC is used for 10Gbps links and for double data rate (DDR) and quad data rate (QDR) Infiniband. But it is the evolution of Infiniband’s roadmap - eight data rate (EDR, 20Gbps per lane) and hexadecimal data rate (HDR, 40Gbps per lane) - as well as the advent of 100m 40 and 100 Gigabit Ethernet links with their four and ten channel designs that will drive AOC demand.

The second largest market for AOC, about $450 million by 2014, and one that surprised Wirbel, is the ‘unassuming’ digital signage.

Until now such signs displaying video have been well served by 1Gbps Ethernet links but now with screens showing live high-definition feeds and four-way split screens 10Gbps feeds are becoming the baseline. Moreover distances of 100m to 1km are common.

PC interconnect is another market where AOC is set to play a role, especially with the inclusion of a high-definition multimedia interface (HDMI) interface as standard with each netbook.

“A netbook has no local storage, using the cloud instead,” says Wirbel. Uploading video from a video camera to the server or connecting video streams to a home screen via HDMI will warrant AOC, says Wirbel.

Home theatre is the fourth emerging application for AOC though Wirbel stresses this will remain a niche application.