Optical integration and silicon photonics: A view to 2021

LightCounting’s report on photonic integration has several notable findings. The first is that only one in 40 optical components sold in the datacom and telecom markets is an integrated device yet such components account for a third of total revenues.

Another finding is that silicon photonics will not have a significant market impact in the next five years to 2021, although its size will grow threefold in that time.

By 2021, one in 10 optical components will be integrated and will account for 40% of the total market, while silicon photonics will become a $1 billion industry by then.

Integrated optics

“Contrary to the expectation that integration is helping to reduce the cost of components, it is only being used for very high-end products,” says Vladimir Kozlov, CEO of LightCounting.

He cites the example of the cost-conscious fibre-to-the-home market which despite boasting 100 million units in 2015 - the highest volumes in any one market - uses discrete parts for its transceivers. “There is very little need for optical integration in this high-volume, low-cost market,” he says

Where integration is finding success is where it benefits device functionality. “Where it takes the scale of components to the next level, meaning much more sophisticated designs than just co-packaged discrete parts,” says Kozlov. And it is because optical integration is being applied to high-end, costlier components that explains why revenues are high despite volumes being only 2.4% of the total market.

Defining integration

LightCounting is liberal in its definition of an integrated component. An electro-absorption modulated laser (EML) where the laser and modulator are on the same chip is considered as an integrated device. “It was developed 20 years ago but is just reaching prime time now with line rates going to 25 gigabit,” says Kozlov.

Designs that integrate multiple laser chips into a transceiver such as a 4x10 gigabit design is also considered an integrated design. “There is some level of integration; it is more sophisticated than four TO-cans,” says Kozlov. “But you could argue it is borderline co-packaging.”

LightCounting forecasts that integrated products will continue to be used for high-end designs in the coming five years. This runs counter to the theory of technological disruption where new technologies are embraced at the low end first before going on to dominate a market.

“We see it continuing to enter the market for high-end products simply because there is no need for integration for very simple optical parts,” says Kozlov.

Silicon photonics

LightCounting does not view silicon photonics as a disruptive technology but Kozlov acknowledges that while the technology has performance disadvantages compared to traditional technologies such as indium phosphide and gallium arsenide, its optical performance is continually improving. “That may still be consistent with the theory of technological disruption,” he says.

There are all these concerns about challenges but silicon photonics does have a chance to be really great

The market is also developing in a way that plays to silicon photonics’ strengths. One such development is the need for higher-speed interfaces, driven by large-scale data centre players such as Microsoft. “Their appetite increases as the industry is making progress,” says Kozlov. “Six months ago they were happy with 100 gigabit, now they are really focused on 400 gigabit.”

Going to 400 gigabit interfaces will need 4-level pulse-amplitude modulation (PAM4) transmitters that will provide new ground for competition between indium phosphide, VCSELs and silicon photonics, says Kozlov. Silicon photonics may even have an edge according to results from Cisco where its silicon photonics-based modulators were shown to work well with PAM4. This is where silicon photonics could even take a market lead: for 400-gigabit designs that require multiple PAM4 transmitters on a chip, says LightCounting.

Another promise silicon photonics could deliver although yet to be demonstrated is the combination of optics and electronics in one package. Such next-generation 3D packaging, if successful, could change things more dramatically than LightCounting currently anticipates, says Kozlov.

“This is the interesting thing about technology, you never really know how successful it will be,” says Kozlov. “There are all these concerns about challenges but silicon photonics does have a chance to be really great.”

But while LightCounting is confident the technology will prove successful sooner of later, getting businesses that use the technology to thrive will require overcoming a completely different set of challenges.

“It is a challenging environment,” warns Kozlov. “There is probably more risk on the business side of things now than on the technology side.”

Avago to acquire CyOptics

- Avago to become the second largest optical component player

- Company gains laser and photonic integration technologies

- The goal is to grow data centre and enterprise market share

- CyOptics achieved revenues of $210M in 2012

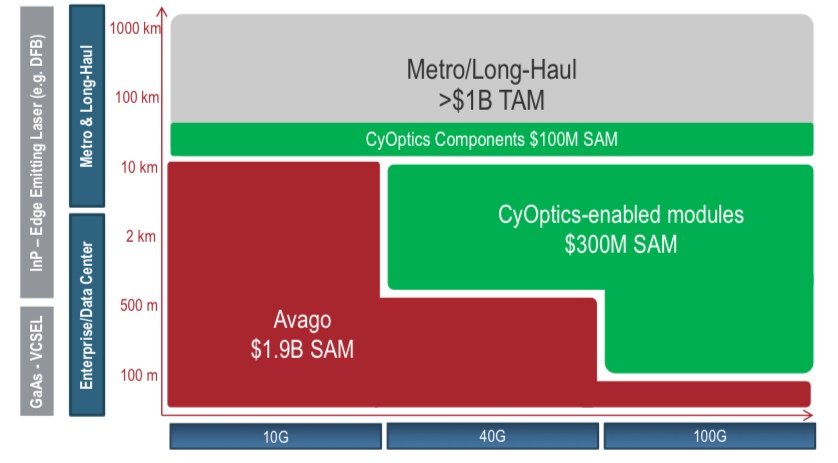

How the acquisition of CyOptics will expand Avago's market opportunities. SAM is the serviceable addressable market and TAM is the total addressable market. Source: Avago

How the acquisition of CyOptics will expand Avago's market opportunities. SAM is the serviceable addressable market and TAM is the total addressable market. Source: Avago

Avago Technologies has announced its plan to acquire optical component player, CyOptics. The value of the acquisition, at US $400M, is double CyOptics' revenues in 2012.

CyOptics' sales were $210M last year, up 21 percent from the previous year. Avago's acquisition will make it the optical component industry's second largest company, behind Finisar, according to market research firm, Ovum. The deal is expected to be completed in the third quarter of the year.

The deal will add indium phosphide and planar lightwave circuit (PLC) technologies to Avago's vertical-cavity surface-emitting laser (VCSEL) and optical transceiver products. In particular, Avago will gain edge laser technology and photonic integration expertise. It will also inherit an advanced automated manufacturing site as well as entry into new markets such as passive optical networking (PON).

Avago stresses its interest in acquiring CyOptics is to bolster its data centre offerings - in particular 40 and 100 Gigabit data centre and enterprise applications - as well as benefit from the growing PON market.

The company has no plans to enter the longer distance optical transmission market beyond supplying optical components.

Significance

Ovum views the acquisition as a shift in strategy. Avago is known as a short distance interconnect supplier based on its VCSEL technology.

"Avago has seen that there are challenges being solely a short-distance supplier, and there are opportunities expanding its portfolio and strategy," says Daryl Inniss, Ovum's vice president and practice leader components.

Such opportunities include larger data centres now being built and their greater use of single-mode fibre that is becoming an attractive alternative to multi-mode as data rates and reach requirements increase.

"Avago's revenues can be lumpy partly because they have a few really large customers," says Inniss.

Another factor motivating the acquisition is that short-distance interconnect is being challenged by silicon photonics. "In the long run silicon photonics is going to win," he says.

What Avago will gain, says Inniss, is one of the best laser suppliers around. And its acquisition will impact adversely other optical module players. "CyOptics is a supplier to several transceiver vendors," says Inniss. "The outlook, two or three years' hence, is decreased business as a merchant supplier."

Inniss points out that CyOptics will represent the second laser manufacturer acquisition this year, following NeoPhotonics's acquisition of Lapis Semiconductor which has 40 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) electro-absorption modulator lasers (EMLs).

These acquisitions will remove two merchant EML suppliers, given that CyOptics is a strong 10Gbps EML player, and lasers are a key technological asset.

See also:

For a 2011 interview with CyOptics' CEO, click here

The CFP2 pluggable module gains industry momentum

Finisar and Oclaro unveiled their first CFP2 optical transceiver products at the recent ECOC exhibition in Amsterdam. JDSU also announced that its ONT-100G test equipment now supports the latest 100Gbps module form factor.

Source: Oclaro

Source: Oclaro

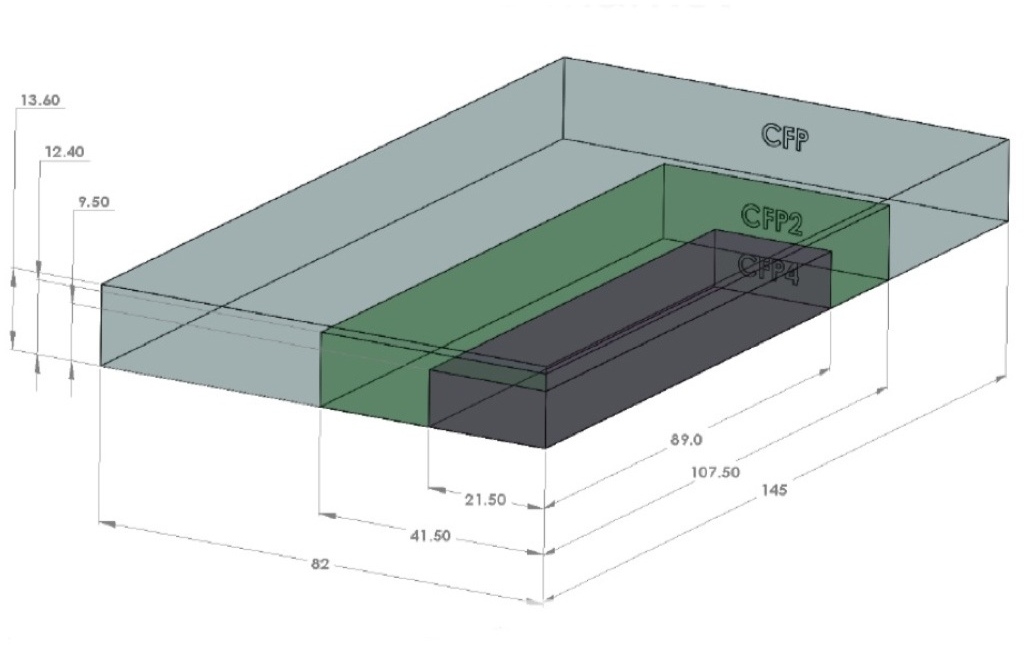

The CFP2 is the follow-on module to the CFP, supporting the IEEE 100 Gigabit Ethernet and ITU OTU4 standards. It is half the size of the CFP (see image) and typically consumes half the power. Equipment makers can increase the front-panel port density from four to eight by migrating to the CFP2.

Oclaro also announced a second-generation CFP supporting the 100GBASE-LR4 10km and OTU4 standards that reduces the power consumption from 24W to 16W. The power saving is achieved by replacing a two-chip silicon-germanium 'gearbox' IC with a single CMOS chip. The gearbox translates between the 10x10Gbps electrical interface and the 4x25Gbps signals interfacing to the optics.

The CFP2, in contrast, doesn’t include the gearbox IC.

"One of the advantages of the CFP2 module is we have a 4x25Gbps electrical interface," says Rafik Ward, vice president of marketing at Finisar. "That means that within the CFP2 module we can operate without the gearbox chip." The result is a compact, lower-power design, which is further improved by the use of optical integration.

"That 2.5x faster [interface of the CFP2] equates to about a 6x greater difficulty in signal integrity issues, microwave techniques etc"

Paul Brooks, JDSU

The transmission part of the CFP module typically comprises four externally modulated lasers (EMLs), each individually cooled. The four transmitter optical sub-assemblies (TOSAs) then interface to a four-channel optical multiplexer.

Finisar's CFP2 design uses a single TOSA holding four distributed feedback (DFB) lasers, a shared thermo-electric cooler and the multiplexer. The result of using DFBs and an integrated TOSA is that Finisar's CFP2 consumes just 8W.

Oclaro uses photonic integration on the receiver side, integrating four receiver optical sub-assemblies (ROSAs) as well as the optical demultiplexer into a single design, resulting in a 12W CFP2.

At ECOC, Oclaro demonstrated interoperability between its latest CFP and the CFP2. “It shows that the new modules will talk to existing ones,” says Robert Blum, director of product marketing for Oclaro's photonic components.

Meanwhile JDSU demonstrated its ONT-100G test set that supports the CFP2 and CFP4 MSAs.

"Initially the [test set] applications are focused on those doing the fundamental building blocks [for the 100G CFP2] – chip vendors, optical module vendors, printed circuit board developers," says Paul Brooks, director for JDSU's high speed transport test portfolio. "We will roll out more applications within the year that cover early deployment and production."

The standards-based client-side interfaces is an attractive market for test and measurement companies. For line-side optical transmission, much of the development work is proprietary such that developing a test set to serve vendors' proprietary solutions is not feasible.

The biggest engineering challenge for the CFP2 is its adoption of high-speed 25Gbps electrical interfaces. "The CFP was based on third generation, mature 10 Gig I/O [input/output]," says Brooks. "To get to cost-effective CFP2 [modules] is a very big jump: that 2.5x faster [interface] equates to about a 6x greater difficulty in signal integrity issues, microwave techniques etc."

The company says that what has been holding up the emergence of the CFP2 module has been the 104-pin connector: "The pluggable connector is the big headache," says Brooks. "The expectation is that very soon we should get some early connectors."

The test equipment also supports developers of the higher-density CFP4 module, and other form factors such as the QSFP2.

JDSU will start shipping its CFP2 test equipment in the first quarter of 2013.

Oclaro's second-generation CFP and the CFP2 transceivers are sampling, with volume production starting in early 2013.

Finisar's CFP2 LR4 product will sample in 2012 and enter volume production in 2013.

Next-gen 100 Gigabit short reach optics starts to take shape

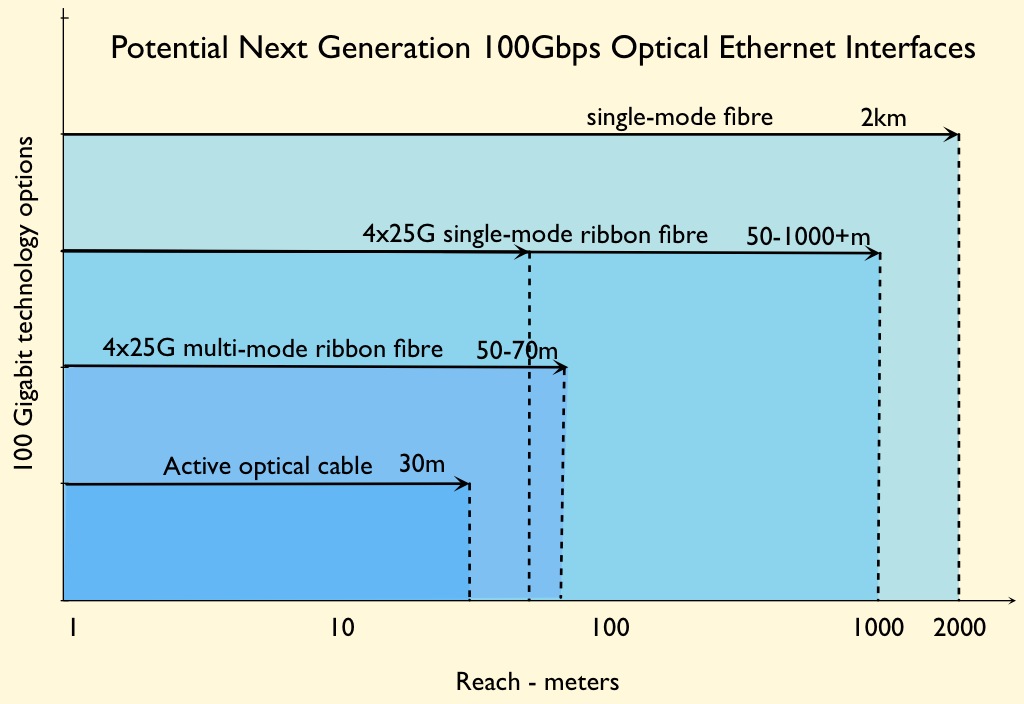

The latest options for 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) interfaces are beginning to take shape following a meeting of the IEEE 802.3 Next Generation 100Gb/s Optical Ethernet Study Group in November.

The interface options being discussed include:

- A parallel multi-mode fibre using a VCSEL with a reach of 50m to 70m. An active optical cable version with a 30m reach, limited by the desired cable length rather than the technology, using silicon photonics or a VCSEL has also been proposed.

- A parallel single-mode fibre using a 1310nm electro-absorption modulated laser (EML) or silicon photonics with a range of 50m to 1000m+.

- A duplex single-mode fiber, using wavelength division multiplexing (WDM) or pulse-width modulation (PAM), an EML or silicon photonics for a 2km reach.

“I think in the end all will be adopted,” says Marek Tlalka, director of marketing at Luxtera. "Users will be able to choose what is most economical."

Jon Anderson, director of technology programme at Opnext, stresses however that these are proposals.

"No decisions were reached by the Study Group on any of these proposals," he says. “The Study Group is only working towards defining objectives for a next-gen 100 Gigabit Ethernet Optics project.” Agreement on technical solutions is outside the scope of the Study Group.

Anderson says there is a general agreement to define a 4x25Gbps multi-mode fibre optical interface. But the issues of reach and multi-mode fibre type (OM3, OM4) are still being studied.

“The Study Group has not reached any agreement on whether a 100GE short reach single-mode objective should be pursued," says Anderson. “Discussion at this point are on reach, power consumption and relative cost of possible solutions with respect to (the 10km) 100GBASE-LR4."