OFC 2024 industry reflections: Part 4

Gazettabyte is asking industry figures for their thoughts after attending the recent OFC show in San Diego. This penultimate part includes the thoughts of Cisco’s Ron Horan, Coherent’s Dr. Sanjai Parthasarathi, and Adtran’s Jörg-Peter Elbers.

Ron Horan, Vice President Product Management, Client Optics Group, Cisco

Several years ago, no one could have predicted how extensive the network infrastructure required to support artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) back-end networks in data centres would be. This year’s OFC answered that question. In a word, immense.

By 2025, the optics total addressable market for AI/ML back-end networks is expected to equal the already substantial front-end network optics market. By 2027, the back-end network optics total addressable market is projected to significantly exceed that of the front-end network. Additionally, the adoption of higher speeds and interface densities in the AI/ML back-end network will likely surpass that of the front-end.

Last year, linear pluggable optics (LPO) advocates heralded the power and cost savings associated with removing the digital signal processor (DSP) from an optics module and driving it directly from the host ASIC. Cisco and others have shown, using data and demos, that the overall power and cost savings are significant. However, in the last year, enthusiasm for this disruptive technology has been checked as concerns about link robustness and accountability have surfaced.

Enter linear receive optics (LRO), where the transmit path gets retimed while the high-power module receiver path moves to a linear receiver, which drives directly to the host ASIC. While not as power or cost friendly as linear pluggable optics, it does reduce power and some cost from the module compared to a fully retimed module while providing some diagnostic support for the link.

Only time and significant interoperability testing will determine whether linear pluggable optics or linear receive links will be robust enough to make them deployable at scale. Additionally, today’s linear pluggable and linear receive solutions have only been shown at 100 gigabits per lane. It is unclear whether 200 gigabits per lane for both approaches can work. Many think not. If not, then 100 gigabit per lane linear pluggable and linear receive optics may be a one-generation technology that is never optimal. The LPO-MSA, an industry effort that included many of the industry’s key companies, was announced before OFC to specify and resolve interoperability and link accountability concerns.

The overall concern about reducing power in the data centre was a strong theme at the show. The linear pluggable optics/ linear receive optics theme was born from this concern. As optics, switches, routers, and GPU servers become faster and denser, data centres cannot support the insatiable need for more power.

However, end users and equipment manufacturers seek alternative ways to lower power, such as liquid cooling and immersion. Liquid cooling uses liquid-filled pipes to remove the heat, which can help cool the optics. Liquid immersion further amplifies the cooling approach by immersing the optics, along with the host switch or GPU server, directly into an inert cooling fluid or placing them just above the fluid in the vapour layer. The ultimate result is to operate the optics at a lower case temperature and save power. It seems each customer is approaching this problem differently.

Last year’s OFC produced the first optics with 200 gigabit per optical lane technology. These solutions assumed a gearbox to a host interface that used 100-gigabit electrical channels. While some early adopters will use systems and optics with this configuration, a more optimal solution using 200 gigabits per lane electrical channels between the host and optics will likely be where we see 200 gigabits per lane optics hit their stride. This year’s show revealed a broader set of optics at 200 gigabit per lane rates. The technology maturity was markedly improved from last year’s early feasibility demos.

This is an exciting time in the optics industry. I look forward to learning what technologies will be introduced at OFC 2025.

Dr. Sanjai Parthasarathi, Chief Marketing Officer, Coherent

The progress in making 200-gigabit VCSELs ready for 200-gigabit PAM-4 optical transmission was a pleasant surprise of the event.

We at Coherent presented a paper on our lithographic aperture VCSEL, while Broadcom’s presentation outlined the technical feasibility of 200-gigabit PAM4 links. While both mentioned that more work is needed, the historic success of VCSEL-based links in short-reach interconnects suggests that the arrival of 200G-capable VCSELs will significantly impact the datacom market.

The feasibility of linear pluggable optics has likely delayed the market acceptance of co-packaged optics. There seems to be widespread consensus that LPO can reduce cost and power while retaining all the advantages of pluggable transceivers – a vibrant ecosystem, deployment flexibility, and a clear distinction of link accountability.

Jörg-Peter Elbers, senior vice president, advanced technology, standards and IPR, Adtran.

At this year’s OFC, discussions were much hotter than the weather. Who would have anticipated rain, winds and chilly temperatures in an always-sunny San Diego?

AI infrastructure created the most buzz at OFC. Accelerated compute clusters for generative AI are expected to drive massive demands for high-speed interconnects inside cloud-scale data centres. Consequently, 800-gigabit, 1.6-terabit, and future 3.2-terabit pluggable optical transceivers for front-end and back-end data centre fabrics stirred a lot of interest. Progress on co-packaged optics was also exciting, yet the technology will only go into deployments where and when pluggable transceivers hit unsurmountable challenges.

Silicon Photonics, indium phosphide, thin-film lithium niobate and VCSEL-based optics compete for design slots in a very competitive intra-data centre market, leading to new partnerships across the pluggable transceiver value chain. Linear receive optics and linear transmit & receive pluggable optics offer opportunities to reduce or eliminate DSP functions where electrical signal integrity permits.

While green ICT (information and communications technology) received a lot of attention at the conference, comments at the OFC Rump Session on this topic were somewhat disenchanting: time-to-market and total-cost-of-ownership drive deployment decisions at hyperscale data centres; lower energy consumption of optics is welcome but not a sufficient driver for architectural change.

On the inter-data centre side, a range of companies announced or demonstrated 800G-ZR/ZR+ transceivers at the show. More surprising was the number of transceiver vendors – including those not traditionally active in this market domain – who have added 400G-ZR QSFP-DD transceivers to their product portfolio. This indicates that the prices of these transceivers may decline faster than anticipated.

As for the next generation, industry consensus is building up behind a single-wavelength 1.6T ZR/ZR+ ecosystem using a symbol rate of some 240 gigabaud. There was a period in which indium phosphide and silicon photonics seemed to have taken over, and LiNbO3 appeared old-fashioned. With the move to higher symbol rates, LiNbO3 – in the form of thin-film Lithium Niobate – is celebrating a comeback: “Lithium Niobate is dead – long live Lithium Niobate!”

The OIF’s largest ever interop demo impressively showed how 400G-ZR+ modules can seamlessly interoperate over long-haul distances using an open-line system optimized for best performance and user-friendly operation. Monitoring and controlling such pluggable modules in IPoWDM scenarios can create operational and organizational challenges and is the subject of ongoing debates in IETF, TIP and OIF. A lean demarcation unit device can be a pragmatic solution to overcome these challenges in the near term. In the access/aggregation domain, the interest in energy-efficient 100G-ZR solutions keeps growing.

As the related OFC workshop showed, growing is also the support for a coherent single-carrier PON solution as the next step in the PON roadmap after 50Gbps very high-speed PON (VHSP).

Overall, there was excitement and momentum at OFC, with the conference and show floor returning to pre-Covid levels.

This is a good basis for the 50th anniversary edition of ECOC, taking place in Frankfurt, Germany, on September 22-26, 2024.

The APC’s blueprint for silicon photonics

The Advanced Photonics Coalition (APC) wants to smooth the path for silicon photonics to become a high-volume manufacturing technology.

The organisation is talking to companies to tackle issues whose solutions will benefit the photonics technology.

The Advanced Photonics Coalition wants to act as an industry catalyst to prove technologies and reduce the risk associated with their development, says Jeffery Maki, Distinguished Engineer at Juniper Networks and a member of the Advanced Photonics Coalition’s board.

Origins

The Advanced Photonics Coalition was unveiled at the Photonic-Enabled Cloud Computing (PECC) Industry Summit jointly held with Optica last October.

The Coalition was formerly known as the Coalition for On-Board Optics (COBO), an industry initiative led by Microsoft.

Microsoft wanted a standard for on-board optics, until then it was a proprietary technology. At the time, on-board optics was seen as an important stepping stone between pluggable optical modules and their ultimate successor, co-packaged optics.

After years of work developing specifications and products, Microsoft chose not to adopt on-board optics in its data centres. Although COBO added other work activities, such as co-packaged optics, the organisation lost momentum and members.

Maki stresses that COBO always intended to tackle other work besides its on-board optics starting point.

Now, this is the Advanced Photonics Coalition’s goal: to have a broad remit to create working groups to address a range of issues.

Tackling technologies

Many standards organisations publish specifications but leave the implementation technologies to their member companies. In contrast, the Advanced Photonics Coalition is taking a technology focus. It wants to remove hurdles associated with silicon photonics to ease its adoption.

“Today, we see the artificial intelligence and machine learning opportunities growing, both in software and hardware,” says Maki. “We see a need in the coming years for more hardware and innovative solutions, especially in power, latency, and interconnects.”

Work Groups

In the past, systems vendors like Cisco or Juniper drove industry initiatives, and other companies fell in line. More recently, it was the hyperscalers that took on the role.

There is less of that now, says Maki: “We have a lot of companies with technologies and good ideas, but there is not a strong leadership.”

The Advanced Photonics Coalition wants to fill that void and address companies’ common concerns in critical areas. “Key customers will then see the value of, and be able to access, that standard or technology that’s then fostered,” says Maki.

The Advanced Photonics Coalition has yet to announce new working groups but it expects to do so in 2024.

One area of interest is silicon photonics foundries and their process design kits (PDKs). Each foundry has a PDK, made up of tools, models, and documentation, to help engineers with the design and manufacture of photonic integrated devices.

“A starting point might be support for more than one foundry in a multi-foundry PDK,” says Maki. “Perhaps a menu item to select the desired foundry where more than one foundry has been verified to support.”

Silicon photonics has long been promoted as a high-volume manufacturing technology for the optical industry. “But it is not if it has been siloed into separate efforts such that there is not that common volume,” says Maki.

Such a PDK effort would identify gaps that each foundry would need to fill. “The point is to provide for more than one foundry to be able to produce the item,” he says.

A company is also talking to the Advanced Photonics Coalition about co-packaged optics. The company has developed an advanced co-packaged optics solution, but it is proprietary.

“Even with a proprietary offering, one can make changes to improve market acceptance,” says Maki. The aim is to identify the areas of greatest contention and remedy them first, for example, the external laser source. “Opening that up to other suppliers through standards adoption, existing or new, is one possibility,” he says.

The Advanced Photonics Coalition is also exploring optical interconnecting definitions with companies. “How we do fibre-attached to silicon photonics, there’s a desire that there is standardisation to open up the market more,” says Maki. “That’s more surgical but still valuable.”

And there are discussions about a working group to address co-packaged optics for the radio access network (RAN). Ericsson is one company interested in co-packaged optics for the RAN. Another working group being discussed could tackle optical backplanes.

Maki says there are opportunities here to benefit the industry.

“Companies should understand that nothing is slowing them down or blocking them from doing something other than their ingenuity or their own time,” he says.

Status

COBO had 50 members earlier in 2023. Now, the membership listed on the website has dropped to 39 and the number could further dip; companies that joined for COBO may still decide to leave.

At the time of writing, an new as yet unannounced member has joined the Advanced Photonics Coalition, taking the membership to 40.

“Some of those companies that left, we think they will return once we get the working groups formed,” says Maki, who remains confident that the organisation will play an important industry role.

“Every time I have a conversation with a company about the status of the market and the needs that they see for the coming years, there’s good alignment amongst multiple companies,” he says.

There is an opportunity for an organisation to focus on the implementation aspects and the various technology platforms and bring more harmony to them, something other standards organisations don’t do, says Maki.

Deutsche Telekom explains its IP-over-DWDM thinking

Telecom operators are always seeking better ways to run their networks. In particular, operators regularly scrutinise how best to couple the IP layer with their optical networking infrastructure.

The advent of 400-gigabit coherent modules that plug directly into an IP router is one development that has caught their eye.

Placing dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) interfaces directly onto an IP router allows the removal of a separate transponder box and its interfacing.

IP-over-DWDM is not a new concept. However, until now, operators have had to add a coherent line card, taking up valuable router chassis space.

Now, with the advent of compact 400-gigabit coherent pluggables developed for the hyperscalers to link their data centres, telecom operators have realised that such pluggables also serve their needs.

BT will start rolling out IP-over-DWDM in its network this year, while Deutsche Telekom has analysed the merits of IP-over-DWDM.

“The adoption of IP-over-DWDM is the subject of our techno-economical studies,” says Werner Weiershausen, senior architect for the transport network at Deutsche Telekom.

Network architecture

Deutsche Telekom’s domestic network architecture comprises 12 large nodes where IP and OTN backbones align with the underlying optical networking infrastructure. These large nodes – points of presence – can be over 1,000km apart.

Like many operators, Deutsche Telekom has experienced IP annual traffic growth of 35 per cent. The need to carry more traffic without increasing costs has led the operators to adopt coherent technology, with the symbol rate rising with each new generation of optical transport technology.

A higher channel bit rate sends more data over an optical wavelength. The challenge, says Weiershausen, is maintaining the long-distance reaches with each channel rate hike.

Deutsche Telekom’s in-house team forecasts that IP traffic growth will slow down to a 20 per cent annual growth rate and even 16 per cent in future.

Weiershausen says this is still to be proven but that if annual traffic growth does slow down to 16-20 per cent, bandwidth growth issues will remain; it is just that they can be addressed over a longer timeframe.

Bandwidth and reach are long-haul networking issues. Deutsche Telekom’s metro networks, which are horse-shoe-shaped, have limited spans overall.

“For metro, our main concern is to have the lowest cost-per-bit because we are fibre- and spectrum-rich, and even a single DWDM fibre pair per metro horseshoe ring offer enough bandwidth headroom,” says Weiershausen. “So it’s easy; we have no capacity problem like the backbone. Also there, we are fibre-rich but can avoid the costly activation of multiple parallel fibre trunks.”

IP-over-DWDM

IP-over-DWDM is increasingly associated with adding pluggable optics onto an IP core router.

“This is what people call IP-over-DWDM, or what Cisco calls it hop-by-hop approach,” says Dr Sascha Vorbeck, head of strategy and architecture IP-core & transport networks at Deutsche Telekom.

Cisco’s routed optical networking – its term for the hop-by-hop approach – uses the optical layer for point-to-point connections between IP routers. As a result, traffic switching and routing occur at the IP layer rather than the optical layer, where optical traffic bypass is performed using reconfigurable optical add/drop multiplexers (ROADMs).

Routed optical networking also addresses the challenge of the rising symbol rate of coherent technology, which must maintain the longest reaches when passing through multiple ROADM stages.

Deutsche Telekom says it will not change its 12-node backbone network to accommodate additional routing stages.

“We will not change our infrastructure fundamentally because this is costly,” says Weiershausen. “We try to address this bandwidth growth with technology and not with the infrastructure change.”

Deutsche Telekom’s total cost-of-ownership analysis highlights that optical bypass remains attractive compared to a hop-by-hop approach for specific routes.

However, the operator has concluded that the best approach is to have both: some hop-by-hop where it suits its network in terms of distances but also using optical bypass for longer links using either ROADM or static bypass technology.

“A mixture is the optimum from our total cost of ownership calculation,” says Weiershausen. “There was no clear winner.”

Strategy

Deutsche Telecom favours coherent interfaces on its routers for its network backbone because it wants to simplify its network. In addition, the operator wants to rid its network of existing DWDM transponders and their short reach – ‘grey’ – interfaces linking the IP router to the DWDM transponder box.

“They use extra power and are an extra capex [capital expenditure] cost,” says Weiershausen. “They are also an additional source of failures when you have in-line several network elements. That said, heat dissipation of long-reach coherent optical DWDM interfaces limited the available IP router interfaces that could have been activated in the past.

For example, a decade ago, Deutsche Telecom tried to use IP-over-DWDM for its backbone network but had to step back to use an external DWDM transponder box due to heat dissipation problems.

The situation may have changed with modern router and optical interface generations, but this is under further study by Deutsche Telecom and is an essential prerequisite for its evolution roadmap.

Deutsche Telecom is still using traditional DWDM equipment between the interconnection of IP routers with grey interfaces. Deutsche Telecom undertook an evaluation in 2020 and calculated a traditional DWDM network versus a hop-by-hop approach. Then, the hop-by-hop method was 20 per cent more expensive. Deutsche Telecom plans to redo the calculations to see if anything has changed.

The operator has yet to decide whether to adopt ZR+ coherent pluggable optics and a hop-by-hop approach or use more advanced larger coherent modules in its routers. “This is not decided yet and depends on pricing evolution,” says Weiershausen.

With the volumes expected for pluggable coherent optics, the expectation is they will have a notable price advantage compared to traditional high-performance coherent interfaces.

But Deutsche Telekom is still determining, believing that conventional coherent interfaces may also come down markedly in price.

SDN controller

Another issue for consideration with IP-over-DWDM is the software-defined networking (SDN) controller.

IP router vendors offer their SDN controllers, but there also is a need for working with third-party SDN controllers.

For example, Deutsche Telekom is a member of the OpenROADM multi-source agreement and has pushed for IP-over-DWDM to be a significant application of the MSA.

But there are disaggregation issues regarding how a router’s coherent optical interfaces are controlled. For example, are the optical interfaces overseen and orchestrated by the OpenROADM SDN controller and its application programming interface (API) or is the SDN controller of each IP router vendor responsible for steering the interfaces?

Deutsche Telekom says that a compromise has been reached for the OpenROADM MSA whereby the IP router vendors’ SDN controllers oversee the optics but that for the solution to work, information is exchanged with the OpenROADM’s SDN controller.

“That way, the path computation engine (PCE) of the optical network layer, including the ROADMs, can calculate the right path to network the traffic. “Without information from the IP router, it would be blind; it would not work,” says Weiershausen.

Automation

Weiershausen says it is not straightforward to say which approach – IP-over-DWDM or a boundary between the IP and optical layers – is easier to automate.

“Principally, it is the same in terms of the information model; it is just that there are different connectivity and other functionalities [with the two approaches],” says Weiershausen.

But one advantage of a clear demarcation between the layers is the decoupling of the lifecycles of the different equipment.

Fibre has the longest lifecycle, followed by the optical line system, with IP routers having the shortest of the three, with new generation equipment launched every few years.

Decoupling and demarcation is therefore a good strategy here, notes Weiershausen.

Acacia's single-wavelength terabit coherent module

- Acacia has developed a 140-gigabaud, 1.2-terabit coherent module

- The module, using 16-ary quadrature amplitude modulation (16-QAM), can deliver an 800-gigabit wavelength over 90 per cent of the links of a North American operator.

Acacia Communications, now part of Cisco, has announced the first 1.2-terabit single-wavelength coherent pluggable transceiver.

And the first vendor, ZTE, has already showcased a prototype using Acacia’s single-carrier 1.2 terabit-per-second (Tbps) design.

The coherent module operates at a symbol rate of up to 140 gigabaud (GBd) using silicon photonics technology. Until now, indium phosphide has always been the material at the forefront of each symbol rate hike.

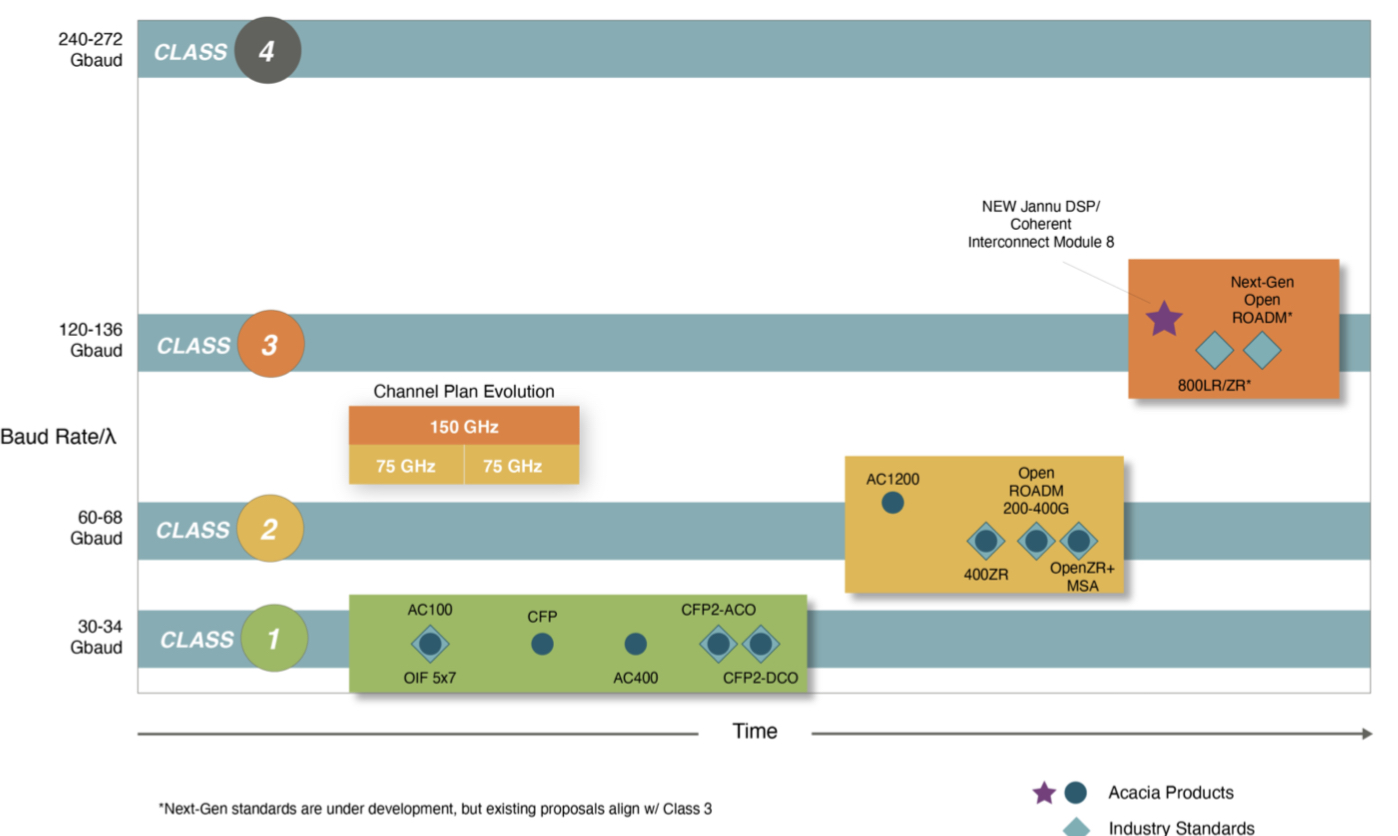

The module uses Acacia’s latest Jannu coherent digital signal processor (DSP), implemented in 5nm CMOS. The coherent transceiver also uses a custom form-factor pluggable dubbed the Coherent Interconnect Module 8 (CIM-8).

Trends

Acacia refers to its 1.2-terabit coherent pluggable as a multi-haul design, a break from its product categorisation as either embedded or pluggable.

“We are introducing a pluggable module that supports what has traditionally been the embedded market,” says Tom Williams, senior director of marketing at Acacia. “It supports high-capacity edge applications all the way out to long-haul and submarine.”

Pluggables are the fastest-growing segment of the coherent market. Whereas the mix of custom embedded designs to pluggable interoperable is 2:1, that is forecast to change with coherent pluggables accounting for two-thirds of the total ports.

Acacia highlights the growth of coherent pluggables with two examples.

Data centre operator Microsoft used Inphi’s (now Marvell’s) ColorZ direct-detect 100-gigabit modules for data centre interconnect for up to 80km whereas now the industry is moving to the 400ZR coherent MSA.

In turn, while proprietary embedded coherent solutions would be used for reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexers (ROADMs), now, interoperable pluggable coherent modules are being adopted with the OpenROADM MSA.

“There is still a significant need in the market for full-performance multi-haul solutions but we think their development needs to be informed and influenced by pluggables,” says Williams.

1.2-terabit capacity

As coherent technology matures, the optical transmission performance is approaching the theoretical limit as defined by Claude Shannon.

“There is still opportunity for improvement,” says Williams. “We still have performance enhancements with each generation but it is becoming more incremental.”

Williams highlights how its latest design offers a 20–25 per cent spectral efficiency improvement compared to Acacia’s AC1200 that uses two wavelengths to deliver up to 1.2Tbps.

“As we increase baud rate, that alone does not give any improvement in spectral efficiency,” says Williams. It is the algorithmic enhancements that still boost performance.

Acacia is adopting an enhanced probabilistic constellation shaping (PCS) algorithm as well as an improved forward-error correction scheme. “There are also some benefits of a single carrier as opposed to using multiple carriers,” says Williams.

Design

The latest design is a natural extension of the AC1200 which can send 400 gigabits over ultra-long-haul distances, 800 gigabits using two wavelengths over most spans, and three 400-gigabit payloads over shorter, network-edge reaches. Now, this can all be done using a single wavelength.

A 150GHz channel is used when transmitting the module’s full rate of 1.2Tbps. And with the module’s adaptive baud rate feature, the rate can be reduced to fit a wavelength in a 75GHz-wide channel. Existing 800-gigabit transmissions use 112.5GHz channel widths and the multi-rate module also supports this spacing.

Williams says 16-QAM is the favoured signalling scheme used for transmission. This is what has been chosen for the 400ZR standard at 64GBd. Doubling the symbol rate means 800 gigabits can be sent using 16-QAM.

Acacia also highlights that future generation coherent designs, what it calls class 4 (see diagram above), will double the symbol rate again to some 240GBd. But the company is not saying whether the technology enabling such rates will be silicon photonics.

The company has long spoken of the benefits of using a silicon packaging approach for its coherent modules in terms of size, power and automated manufacturing. But as the symbol rate doubles, packaging plays a key role to help tackle challenging radio frequency (RF) design issues.

Acacia stacks the driver and trans-impedance amplifier (TIA) circuitry directly on top of its photonic integrated circuit (PIC) while its coherent DSP is also packaged as part of the design. “This gives us much better signal integrity than if we have the optics and DSP packaged separately,” says Williams.

The key to the design is getting the silicon photonics – the optical modulator, in particular – operating at 140GBd. “If you can, the packaging advantages of silicon are significant,” says Williams.

Acacia points out that with the migration of traffic from 100GbE to 400GbE it makes sense to offer a single-wavelength multi-rate design. And 400GbE will remain the mainstay traffic for a while. But once the transition to 800 gigabit occurs, the idea of supporting two coherent wavelengths – a future dual-wavelength “AC2400” – may make sense.

CIM-8

Acacia is using its own form factor and not a multi-source agreement (MSA) because the 1.2-terabit technology exceeds all existing client-side data rates.

In turn, the power consumption of the 1.2-terabit coherent module requires a custom form factor while launching an MSA based on the CIM-8 would have tipped off the competition, says Williams.

That said, Acacia has made no secret that its next high-end design following on from its 64GBd AC1200 would double the symbol rate and that the company would skip the 96GBd rate used by vendors such as Ciena, Huawei and Infinera already offering 800-gigabit wavelength systems.

For Acacia’s multi-rate design that needs to address submarine applications, the goal is to maximise transmission performance. In contrast, for a ZR+ coherent design that fits in a QSFP-DD, the limited power budget of the module constrains the design’s performance.

With 5nm Jannu DSP, Acacia realised it could not fit the design in the QSFP-DD or OSFP. But it could produce a pluggable multi-haul design with its CIM-8 that is slightly larger than the CFP2 form factor. And pluggables are advantageous when 4-8 can be fitted in a one-rack-unit (1RU) platform.

Acacia says its 140GBd module using 16-QAM will deliver an 800-gigabit wavelength over 90 per cent of the links of a North American operator. For the remaining, longest-distance links (the 10 per cent), it will revert to 400 gigabits.

In contrast, existing 800-gigabit systems operating at 96GBd cover up to 20 per cent of the links before having to revert to the slower speed, says Acacia.

Applications

Hyperscaler data centre operators are the main drivers for 1.2Tbps interconnects. The interface would typically be used in the metro to link smaller data centres to a larger aggregation data centre.

“The 1.2-terabit interface is just trying to maximise cost per bit; pushing more bits over the same set of optics,” says Williams.

The communications service providers’ requirements, meanwhile, are focussed on 400 gigabits and at some point will migrate to 800 gigabits, says Williams.

Several system vendors are expected to announce products using the new module in the coming months.

ADVA’s 800-gigabit CoreChannel causes a stir

ADVA’s latest addition to its FSP 3000 TeraFlex platform provides 800-gigabit optical transmission. But the announcement has caused a kerfuffle among its optical transport rivals.

ADVA’s TeraFlex platform supports various coherent optical transport sleds, a sled being a pluggable modular unit that customises a platform’s functionality.

The coherent sleds use Cisco’s (formerly Acacia Communication’s) AC1200 optical engine. Cisco completed the acquisition of Acacia in March.

The AC1200 comprises a 16nm CMOS Pico coherent digital signal processor (DSP) that supports two wavelengths, each up to 600-gigabit, and two photonic integrated circuits (PICs), for a maximum capacity of 1.2 terabits.

The latest sled from ADVA, dubbed CoreChannel, supports an 800-gigabit stream in a single channel.

ADVA states in its press release that the CoreChannel uses “140 gigabaud (GBd) sub-carrier technology” to deliver 800-gigabit over distances exceeding 1,600km.

This, the company says, improves reach by over 50 per cent compared with state-of-the-art 95GBd symbol rate coherent technologies.

It is these claims that have its rivals reacting.

“Despite their claims – they are not using actual digital sub-carriers,” says one executive from a rival optical transport firm, adding that what ADVA is doing is banding two independent 70GBd 400-gigabit wavelengths together and trying to treat that as a single 800-gigabit signal.

“This isn’t necessarily a bad solution for some applications – each network operator can decide that for themselves,” says the executive. However, he stresses that the CoreChannel is not an 800-gigabit single-channel solution and uses 4th generation 16nm CMOS DSP technology rather than the latest 5th generation, 7nm CMOS DSP technology.

A second executive, from another optical transport vendor providing 800-gigabit single-wavelength solutions, adds that ADVA’s claim of 140GBd is too ‘creative’ for a two-lambda solution.

“It’s not a real 800 gigabit. Not that this must be bad, but one should call things as they are,” the spokesperson said. “What matters to the operators is the cost, power consumption, reach and density of a modem; the number of lambdas is more of an internal feature.”

CoreChannel

ADVA confirms it is indeed using Cisco’s Pico coherent DSP to drive two wavelengths, each at 400 gigabits-per-second (Gbps).

“You can say the CoreChannel is a less challenging requirement because we are not driving it [the Pico DSP] to the maximum modulation or constellation complexity,” says Stephan Rettenberger, senior vice president, marketing and investor relations at ADVA. “It is the lower end of what the AC1200 can do.”

Until now the two wavelengths have been combined externally, and have not been integrated from a software or a command-and-control approach.

“The CoreChannel sled is just another addition to the TeraFlex toolbox,” says Rettenberger. “It has one physical line interface that drives an 800Gbps stream using two wavelengths, each one around 70GBd, that are logically and physically combined.”

The resulting two-wavelength 800-gigabit stream sits within a 150GHz channel. However, the channel width can be reduced to 125GHz and even 112.5GHz for greater spectral efficiency.

ADVA says the motivation for the design is the customers’ requirement for lower-cost transport and the ability to easily transport 400 Gigabit Ethernet (GbE) client signals.

“With this 800-gigabit line speed, you can go something like 2,000km, that is 50-100 per cent more than what 95GBd single-wavelengths solutions will do,“ says Rettenberger. “And you can also drive it at 400 gigabits and you can do something like 6,000km.”

The reaches quoted are based on a recent field trial involving ADVA.

ADVA uses a single DSP, similar to the latest 800-gigabit systems from Ciena, Huawei and Infinera. Alongside the DSP are two non-hermetically-sealed PICs whereas the 95GBd indium-phosphide solutions use a single hermetically sealed gold box.

ADVA’s solution also requires two lasers whereas the 800-gigabit single-wavelength solutions use one laser.

“Yes, we have two lasers versus one but that is not killing the cost,” says Rettenberger. “And it is also not killing the power consumption because the PIC is so much more power efficient.”

Rettenberger stresses that ADVA is not saying its offering is necessarily a better solution. “But it is a very interesting way to drive 800 gigabits further than these 95 gigabaud solutions,” says Rettenberger. “It has the same cost, space, power efficiency, just greater reach.”

ADVA also agrees that it is not using electrical sub-carriers such as Infinera uses but it is using optical sub-carrier technology.

These two wavelengths are combined logically and also from a physical port interface point of view to fit within a 150GHz window.

The 95GBd, in contrast, is an interim symbol rate step and the resulting 112.5GHz channel width doesn’t easily fit with legacy 25GHz and 50GHz band increments, says ADVA, while the 150GHz band the CoreChannel sled uses is the same channel width that will be used once single-wavelength 140GBd technology becomes available.

Acacia has also long talked about the merit of doubling the baud rate suggesting Cisco’s successor to the AC1200 will have a 140GBd symbol rate. Such a design is expected in the next year or two.

“We feel this [CoreChannel] implementation is already future-proofed,” says Rettenberger.

ADVA says it undertook this development in collaboration with Acacia.

Acacia announced a dual-wavelength single-channel AC1200 solution in 2019. Then, the company unveiled its AC1200-SC2 that delivers 1.2 terabits over an optical channel.

The SC2 (single chip, single channel) is an upgrade of Acacia’s AC1200 module in that it sends 1.2 terabits using two sub-carriers that fit in a 150GHz-wide channel.

Customer considerations

Choosing an optical solution comes down to five factors, each having its weight depending on the network application, says the first executive.

These are capacity-per-wavelength, cost-per-bit, capacity-per- optical-engine or -module, spectral efficiency and hence capacity-per-fibre, and power-per-bit.

“Each is measured for a given distance/ network application,” says the executive. “And the reason the weight changes for different applications is that the importance of each factor is different at different points in the network. For example, the importance of spectral efficiency changes depending on how expensive it is to light up a link (fibre and line system costs).”

For long-haul and submarine, spectral efficiency is the most important factor, while for metro it is typically cost-per-bit. Meanwhile, for data centre interconnect applications, it’s a mix between cost-per-bit and power-per-bit. Capacity-per-wave and capacity-per-optical-engine are valuable because they can reduce the number of wavelengths and modules that need to be deployed, reducing operating expenses and accelerating service activation.

“The reason that 5th generation [7nm CMOS technology] is superior to fourth generation [16nm] DSP technology is that it provides superior performance in every single one of those key criteria,” says the executive. “This fact minimised any potential benefits that could be achieved by banding together two wavelengths using 4th generation technology when compared to a single wavelength using 5th generation technology.”

“It sounds like others feel we have misled the market; that was not the intent,” says Rettenberger.

ADVA does not make its own coherent DSP so it doesn’t care if the chip is implemented using a 16nm, 7nm or a 5nm CMOS process.

“We are trying to build a good solution for transmitting 400GbE signals and, for us, the Pico chip is a wonderful piece of technology that we have now implemented in four different [sled] variants of TeraFlex.”

Verizon tips silicon photonics as a key systems enabler

Part 3: An operator view

Glenn Wellbrock is upbeat about silicon photonics’ prospects. Challenges remain, he says, but the industry is making progress. “Fundamentally, we believe silicon photonics is a real enabler,” he says. “It is the only way to get to the densities that we want.”

Glenn Wellbrock

Glenn Wellbrock

Wellbrock adds that indium phosphide-based photonic integrated circuits (PICs) can also achieve such densities.

But there are many potential silicon photonics suppliers because of its relatively low barrier to entry, unlike indium phosphide. "To date, Infinera has been the only real [indium phosphide] PIC company and they build only for their own platform,” says Wellbrock.

That an operator must delve into emerging photonics technologies may at first glance seem surprising. But Verizon needs to understand the issues and performance of such technologies. “If we understand what the component-level capabilities are, we can help drive that with requirements,” says Wellbrock. “We also have a better appreciation for what the system guys can and cannot do.”

Verizon can’t be an expert in the subject, he says, but it can certainly be involved. “To the point where we understand the timelines, the cost points, the value-add and the risk factors,” he says. “There are risk factors that we also want to understand, independent of what the system suppliers might tell us.”

The cost saving is real, but it is also the space savings and power saving that are just as important

All the silicon photonics players must add a laser in one form or another to the silicon substrate since silicon itself cannot lase, but pretty much all the other optical functions can be done on the silicon substrate, says Wellbrock: “The cost saving is real, but it is also the space savings and power saving that are just as important.”

The big achievement of silicon photonics, which Wellbrock describes as a breakthrough, is the getting rid of the gold boxes around the discrete optical components. “How do I get to the point where I don’t have fibre connecting all these discrete components, where the traces are built into the silicon, the modulator is built in, even the detector is built right in.” The resulting design is then easier to package. “Eventually I get to the point where the packaging is glass over the top of that.”

So what has silicon photonics demonstrated that gives Verizon confidence about its prospects?

Wellbrock points to several achievements, the first being Infinera’s PICs. Yes, he says, Infinera’s designs are indium phosphide-based and not silicon photonics, but the company makes really dense, low-power and highly reliable components.

He also cites Cisco’s silicon photonics-based CPAK 100 Gig optical modules, and Acacia, which is applying silicon photonics and its in-house DSP-ASICs to get a lower power consumption than other, high-end line-side transmitters.

Verizon believes the technology will also be used in CFP4 and QSFP28 optical modules, and at the next level of integration that avoids pluggable modules on the equipment's faceplate altogether.

But challenges remain. Scale is one issue that concerns Verizon. What makes silicon chips cheap is the fact that they are made in high volumes. “It [silicon photonics] couldn’t survive on just the 100 gigabit modules that the telecom world are buying,” says Wellbrock.

If these issues are not resolved, then indium phosphide continues to win for a long time because that is where the volumes are today

When Verizon asks the silicon photonics players about how such scale will be achieved, the response it gets is data centre interconnect. “Inside the data centre, the optics is growing so rapidly," says Wellbrock. "We can leverage that in telecom."

The other issue is device packaging, for silicon photonics and for indium phosphide. It is ok making a silicon-photonics die cheaply but unless the packaging costs can be reduced, the overall cost saving is lost. ”How to make it reliable and mainstream so that everyone is using the same packaging to get cost down,” says Wellbrock.

All these issues - volumes, packaging, increasing the number of applications a single part can be applied to - need to be resolved and almost simultaneously. Otherwise, the technology will not realise its full potential and the start-ups will dwindle before the problems are fixed.

“If these issues are not resolved, then indium phosphide continues to win for a long time because that is where the volumes are today,” he says.

Verizon, however, is optimistic. “We are making enough progress here to where it should all pan out,” says Wellbrock.

The post-100 Gigabit era

Feature: Beyond 100G - Part 4

The latest coherent ASICs from Ciena and Alcatel-Lucent coupled with announcements from Cisco and Huawei highlight where the industry is heading with regard high-speed optical transport. But the announcements also raise questions too.

Source: Gazettabyte

Source: Gazettabyte

Observations and queries

- Optical transport has had a clear roadmap: 10 to 40 to 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps). 100Gbps optical transport will be the last of the fixed line-side speeds.

- After 100Gbps will come flexible speed-reach deployments. Line-side optics will be able to implement 50Gbps, 100Gbps, 200Gbps or even faster speeds with super-channels, tailored to the particular link.

- Variable speed-reach designs will blur the lines between metro and ultra long-haul. Does a traditional metro platform become a trans-Pacific submarine system simply by adding a new line card with the latest coherent ASIC boasting transmit and receive digital signal processors (DSPs), flexible modulation and soft-decision forward error correction?

Source: Gazettabyte

- The cleverness of optical transport has shifted towards electronics and digital signal processing and away from photonics. Optical system engineers are being taxed as never before as they try to extend the reach of 100, 200 and 400Gbps to match that of 10 and 40Gbps but what is key for platform differentiation is the DSP algorithms and ASIC design.

- Optical is the new radio. This is evident with the adding of a coherent transmit DSP that supports the various modulation schemes and allows spectral shaping, bunching carriers closer to make best use of the fibre's bandwidth.

- The radio analogy is fitting because fibre bandwidth is becoming a scarce resource. Usable fibre capacity has more than doubled with these latest ASIC announcements. Moving to 400Gbps doubles overall capacity to some 18 Terabits. Spectral shaping boosts that even further to over 23 Terabits. Last week 8.8 Terabits (88x100Gbps) was impressive.

- Maximising fibre capacity is why implementing single-carrier 100Gbps signals in 50GHz channels is now important.

- Super-channels, combining multiple carriers, have a lot of operational merits (see the super-channel section in the Cisco story). Infinera announced its 500Gbps super-channel over 250GHz last year. Now Ciena and Alcatel-Lucent highlight how a dual-carrier, dual-polarisation 16-QAM approach in 100GHz implements a 400Gbps signal.

- Despite all the talk of 16-QAM and 400Gbps wavelengths, 100Gbps is still in its infancy and will remain a key technology for years to come. Alcatel-Lucent, one of the early leaders in 100Gbps, has deployed 1,450 100 Gig line units since it launched its system in June 2010.

- Photonic integration for coherent will remain of key importance. Not so much in making yet more complex optical structures than at 100Gbps but shrinking what has already been done.

- Is there a next speed after 100Gbps? Is it 200Gbps until 400Gbps becomes established? Is it 500Gbps as Infinera argues? The answer is that it no longer matters. But then what exactly will operators use to assess the merits of the different vendors' platforms? Reach, power, platform density, spectral efficiency and line speeds are all key performance parameters but assessing each vendor's platform has clearly got harder.

- It is the system vendors not the merchant chip makers that are driving coherent ASIC innovation. The market for 100Gbps coherent merchant chips will remain an important opportunity given the early status of the market but how will coherent merchant chip vendors compete, several of them startups, with the system vendors' deeper pockets and sophisticated ASIC designs?

- Optical transponder vendors at least have more scope for differentiation but it is now also harder. Will one or two of the larger module makers even acquire a coherent ASSP maker?

- Infinera announced its 100G coherent system last year. Clearly it is already working on its next-generation ASIC. And while its DTN-X platform boasts a 500Gbps super-channel photonic chip, its overall system capacity is 8 Terabit (160x50Gbps, each in 25GHz channels). How will Infinera respond, not only with its next ASIC but also its next-generation PIC, to these latest announcements from Ciena and Alcatel-Lucent?

Cisco Systems' 100 Gigabit spans metro to ultra long-haul

Cisco Systems has demonstrated 100 Gigabit transmission over a 3,000km span. The coherent-based system uses a single carrier in a 50GHz channel to transmit at 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps). According to Cisco, no Raman amplification or signal regeneration is needed to achieve the 3,000km reach.

Feature: Beyond 100G - Part 2

"The days of a single modulation scheme on a part are probably going to come to an end in the next two to three years"

Greg Nehib, Cisco

The 100Gbps design is also suited to metro networks. Cisco's design is compact to meet the more stringent price and power requirements of metro. The company says it can fit 42, 100Gbps transponders in its ONS 15454 Multi-service Transport Platform (MSTP), which is a 7-foot rack. "We think that is double the density of our nearest competitor today," claims Greg Nehib, product manager, marketing at Cisco Systems.

Also shown as part of the Cisco demonstration was the use of super-channels, multiple carriers that are combined to achieve 400 Gigabit or 1 Terabit signals.

Single-carrier 100 Gigabit

Several of the first-generation 100Gbps systems from equipment makers use two carriers (each carrying 50Gbps) in a 50GHz channel, and while such equipment requires lower-speed electronics, twice as many coherent transmitters and receivers are needed overall.

Alcatel-Lucent is one vendor that has a single-carrier 50GHz system and so has Huawei. Ciena via its Nortel acquisition offers a dual-carrier 100Gbps system, as does Infinera. With Ciena's announcement of its WaveLogic 3 chipset, it is now moving to a single-carrier solution. Now Cisco is entering the market with a single-carrier system.

"When you have a single carrier, you can get upwards of 96 channels of 100Gbps in the C-band," says Nehib. "The equation here is about price, performance, density and power."

What has been done

Cisco's 100Gbps design fits on a 1RU (rack unit) card and uses the first 100Gbps coherent receiver ASIC designed by the CoreOptics team acquired by Cisco in May 2010.

The demonstrated 3,000km reach was made using low-loss fibre. "This is to some degree a hero experiment," says Nehib. "We have achieved 3,000km with SMF ULL fibre from Corning; the LL is low loss." Normal fibre has a loss of 0.20-0.25dB/km while for ULL fibre it is in the 0.17dB/km range.

"You can do the maths and calculate the loss we are overcoming over 3,000km. We just want to signal that we have very good performance for ultra long-haul," says Nehib, who admits that results will vary in networks, depending on the fibre.

Nehib says Cisco's coherent receiver achieves a chromatic dispersion tolerance of 70,000 ps/nm and 100ps differential group delay. Differential group delay is a non-linear effect, says Nehib, that is overcome using the DSP-ASIC. The greater the group delay tolerance, the better the distance performance. These metrics, claims Cisco, are currently unmatched in the industry.

The company has not said what CMOS process it is using for its ASIC design. But this is not the main issue, says Nehib: "We are trying to develop a part that is small so that it fits in many different platforms, and we can now use a single part number to go from metro performance all the way to ultra long-haul."

Another factor that impacts span performance is the number of lit channels. Cisco, in the test performed by independent test lab EANTC, the European Advanced Network Test Center, used 70 wavelengths. "With 70 channels the performance would have been very close to what we would have achieved with [a full complement of] 80 channels," says Nehib.

Super-channels

A super-channel refers to a signal made up of several wavelengths. Infinera, with its DTN-X, uses a 500Gbps super-channel, comprising five 100Gbps wavelengths.

Using a super-channel, an operator can turn up multiple 100Gbps channels at once. If an operator wants to add a 100Gbps wavelength, a client interface is simply added to a spare 100Gbps wavelength making up the super-channel. In contrast turning up a 100Gbps wavelength in current systems usually requires several days of testing to ensure it can carry live traffic alongside existing links.

Another benefit of super-channels is scale by turning up multiple wavelengths simultaneously. As traffic grows so does the work load on operators' engineering teams. Super-channels aid efficiency.

"There is one other point that we hear quite often," says Nehib. "One other attraction of super-channels is overall spectral efficiency." The carriers that make up the signal can be packed more closely, expanding overall fibre capacity.

"Just like with 10 Gig, we think at some point in the future the 100 Gig network will be depleted, especially in the largest networks, and operators will be interested in 400 Gig and Terabit interfaces," says Nehib. "If that wavelength can further benefit from advanced modulation schemes and super-channels through flex[ible] spectrum deployment then you can get more total bandwidth on the fibre and better utilisation of your amplifiers."

Cisco's 100Gbps lab demonstration also showed 400 Gigabit and 1 Terabit super-channels, part of its research work with the Politechnico di Torino. "We are going to move on to other advanced modulation techniques and deliver 400 Gigabit and Terabit interfaces in future," says Nehib.

Existing 100Gbps systems use dual-polarisation, quadrature phase-shift keying (DP-QPSK). Using 16-QAM (quadrature amplitude modulation) at the same baud rate doubles the data rate. Using 16-QAM also benefits spectral utilisation. If the more intelligent modulation format is used in a super-channel format, and the signal is fitted in the most appropriate channel spacing using flexible spectrum ROADMs, overall capacity is increased. However, the spectral efficiency of 16-QAM comes at the expense of overall reach.

"You are able to best match the rate to the reach to the spectrum," says Nehib. "The days of a single modulation scheme on a part are probably going to come to an end in the next two to three years."

Cisco has yet to discuss the addition of a coherent transmitter DSP which through spectral shaping can bunch wavelengths. Such an approach has just been detailed by Ciena with its WaveLogic 3 and Alcatel-Lucent with its 400 Gig photonic service engine.

For the Terabit super-channel demonstration, Cisco used 16-QAM and a flexible spectrum multiplexer. "The demo that we showed is not necessarily indicative of the part we will bring to market," says Nehib, pointing out that it is still early in the development cycle. "We are looking at the spectral efficiency of super-channels, different modulation schemes, flex-spectrum multiplexer, availability, quality, loss etc.," says Nehib. "We have not made firm technology choices yet."

Cisco's 100Gbps system is in trials with some 40 customers and can be ordered now. The product will be generally available in the near future, it says.

Further reading:

Light Reading: EANTC's independent test of Cisco's CloudVerse architecture. Part 4: Long-haul optical transport

Cisco's P-OTS: Denser and distributed

Cisco claims the CPT is its second-generation packet optical transport system (P-OTS), complementing the ONS 15454. But some analysts view the CPT as the vendor’s first true packet optical transport product.

"This announcement is an acknowledgement that P-OTS equipment is important and that operators are insisting on it"

"This announcement is an acknowledgement that P-OTS equipment is important and that operators are insisting on it"

Sterling Perrin, Heavy Reading

The CPT family comprises the CPT 200 and CPT 600 platforms, while the CPT 50 port extension shelf enables the CPT products to be implemented as a distributed switch architecture.

Gazettabyte spoke to Stephen Liu, manager, service provider marketing at Cisco Systems about the announcement and asked three analysts on the significance of Cisco’s CPT, how the product family advances packet optical transport and how the platforms will benefit operators.

Carrier packet transport family

The CPT platforms are aimed at operators transitioning their metro networks from traditional SONET/SDH to packet-based transport.

Cisco says the CPT is its second-generation P-OTS. A first generation P-OTS supports dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) with some Ethernet capability. “The truly integrated P-OTS that unites the simplicity of optical delivery with packet routing is in the second generation,” says Cisco’s Liu.

Market research firm, Heavy Reading, defines P-OTS as a platform that combines SONET/SDH, connection-oriented Ethernet, DWDM and, depending on where the platform is used within the network, also optical transport network (OTN) switching and reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexers (ROADMs). The global P-OTS market will total $870 million in 2010, says Heavy Reading.

The CPT combines DWDM, OTN, Ethernet, multi-protocol label switching – transport profile (MPLS-TP) and ROADMs. MPLS-TP is a stripped down version of the multi-protocol label switching (MPLS) protocol and is used for point-to-point communication. MPLS-TP’s ability to interoperate with IP-MPLS allows operators to combine packet-based technology with transport control in the access and aggregation part of the network, says Cisco.

So what is new with the introduction of the CPT platforms? “The ability to do high-density packet optical transport with MPLS-TP,” says Liu.

Cisco has fitted 160 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) switching capacity into the two-rack-sized CPT 200 platform and 480Gbps in the six-rack CPT 600. The respective platform port counts are 176 Gigabit Ethernet (GbE) and 352 GbE ports, says Liu.

Cisco also stresses the functionality integrated into the dense platforms. “We have ROADMs coming together with transponders that do the electrical-to-optical conversion, and the TDM/Ethernet switching functions,” says Liu. “It takes about 30 inches of ROADM/transponder and TDM/Ethernet switching functions on separate platforms; with the CPT it is condensed into 10.5 inches of rack space.”

The result, says Liu, is a 60% operational expense (OpEx) saving in power consumption, cooling and space. Cisco also claims that unifying the management of the optical and packet transport domains will result in a 20% OpEx saving.

The CPT 50 satellite shelf complements the CPT platforms. The CPT 50 has 44 GbE ports and four 10GbE uplink ports. “The shelf can be deployed locally next to a CPT platform or up to 80km away, but from a management point-of-view it all looks like a single box,” says Liu.

The platforms do not support 40 or 100Gbps interfaces but that is part of the product roadmap, says Liu. Earlier this year, Cisco acquired 40 and 100 Gigabit transport specialist, CoreOptics. Nor will the platform family be limited to the metro. “Long-haul opportunities are certainly open to us,” says Liu.

Cisco says that the CPT platforms are being trialled and will be available from 1Q of 2011. Several large operators including Verizon, XO Communications and BT are in various stages of platform evaluation.

Analysts’ comments

Sterling Perrin, senior analyst at Heavy Reading

We believe the CPT is Cisco’s most significant optical announcement since its acquisition spree at the beginning of the decade.

Cisco has always positioned its legacy product, the ONS 15454, as packet transport but really it is a multi-service provision platform (MSPP) – or as Cisco calls it, a multi-service transport platform (MSTP) – with SONET/SDH and DWDM. We have not counted that as a P-OTS. What it is doing now is entering the [P-OTS] market.

Cisco is an IP router and Ethernet switch company and is strong on IP-over-DWDM. It has pushed that story to operators for years and while that has been happening, there has been the packet optical transport trend which has been gaining steam. Vendors have either used P-OTS for next-generation networks or have had a dual strategy of switches and routers and P-OTS. Cisco have always been in the switch-router space. This announcement is an acknowledgement that P-OTS equipment is important and that operators are insisting on it.

Cisco will be competitive with the CPT based on its newness. The density looks impressive – 480Gbps for the six-rack and 160Gbps for the two-rack platform. But this is a generational thing; in time as everyone else releases their next product, they will also have a dense platform. But for now it is a differentiator. The remote shelf is also interesting but it is unclear to what degree that will be telling with operators.

As for the operators mentioned in the Cisco press release, Verizon has already picked Fujitsu and Tellabs as the P-OTS suppliers for its metro and regional networks. The big opportunity with Verizon is in the core, and the first two CPT platforms are not for core.

Mention of BT is also interesting as the operator is in favour of the opposite approach, based on switches and routers from Alcatel-Lucent and Juniper, and has moved away from P-OTS. XO is probably the most likely operator [of the three mentioned] to adopt the platform and already uses Cisco’s ONS 15454.

The opportunity for Cisco is protecting the ONS 15454 customer base that is looking to move from MSPPs to packet optical transport.

Heavy Reading believes the standalone DWDM and MSPP markets are declining, but will remain large markets for the next two years. Accordingly, it makes sense for Cisco to continue supporting the legacy product line.

Eve Griliches, managing partner, ACG Research

The CPT is more along the lines of a purpose built P-OTS than some variations that have came to market. It has all the requirements a P-OTS should have including a hybrid switch fabric that supports packet and OTN. I suspect the packet functionality is very good, and possibly better than other transport carriers have delivered, but the operators are still testing and they will speak soon. I do know that operators I've spoken with are already very impressed with what they’ve seen.

"Operators I've spoken with are already very impressed with what they’ve seen"

Eve Griliches, ACG Research

In terms of how the CPT will benefit operators, the CPT is a metro aggregation P-OTS box, and it will have to compete with Tellabs and Fujitsu who have been shipping equipment for the metro for two years. But Cisco will likely bring better packet functionality, which is what operators have been waiting for.

Rick Talbot, senior analyst, transport and routing infrastructure, Current Analysis

Cisco is introducing a product into a space recently defined by other vendors – packet-based access/ aggregation devices for backhaul, currently mobile backhaul. Example devices are the Alcatel-Lucent 1850 TSS-100, ECI Telecom’s BG-64 and the Ericsson OMS 1410.

"The CPT will likely blur the line between metro P-OTS and packet-based access/ aggregation devices"

Rick Talbot, Current Analysis

CPT brings quite a significant advantage in port density and packet-switching capacity. The CPT 200’s 160Gbps capacity is twice that of the OMS 1410, the current leader in that category. The CPT 600 boasts the capacity of a full metro P-OTS in a chassis the size of a small MSPP. From Cisco’s perspective, the CPT product line is not about introducing a new access/ aggregation device but extending the metro architecture closer to cell towers and end-users.

The CPT will likely blur the line between metro P-OTS and packet-based access/ aggregation devices. It has a modest size and power consumption. It also extends MPLS, in the form of MPLS-TP, to the very edge of the operator’s network, enabling a single end-to-end packet-forwarding method.

The high capacity and low-power consumption of the CPT will, of course, save operators OpEx and CapEx. In addition, the platform extends a single connection-oriented management view to the end-user site, minimising management expense.

The flexibility of the platform will further benefit the operator if and when the operator deploys cache content storage at the network edge. But such deployment of servers beyond the central office remains to be seen.

Related links:

See also Intune Networks' packet optical transport platform

AT&T domain suppliers

|

Date |

Domain |

Partners |

|

Sept 2009 |

Wireline Access |

Ericsson |

|

Feb 2010 |

Radio Access Network |

Alcatel-Lucent, Ericsson |

|

April 2010 |

Optical and transport equipment |

Ciena |

|

July 2010 |

IP/MPLS/Ethernet/Evolved Packet Core |

Alcatel-Lucent, Juniper, Cisco |

The table shows the selected players in AT&T's domain supplier programme announced to date.

AT&T has stated that there will likely be eight domain supplier categories overall so four more have still to be detailed.

Looking at the list, several thoughts arise:

- AT&T has already announced wireless and wireline infrastructure providers whose equipment spans the access network all the way to ultra long-haul. The networking technologies also address the photonic layer to IP or layer 3.

- Alcatel-Lucent and Ericsson already play in two domains while no Asian vendor has yet to be selected.

- One or two more players may be added to the wireline access and optical and transport infrastructure domains but this part of the network is pretty much done.

So what domains are left? Peter Jarich, service director at market research firm Current Analysis, suggests the following:

- Datacentre

- OSS/BSS

- IP Service Layer (IP Multimedia Subsystem, subscriber data management, service delivery platform)

- Voice Core (circuit, softswitch)

- Content Delivery (IP TV, etc.)

AT&T was asked to comment but the operator said that it has not detailed any domains beyond those that have been announced.

|

Date |

Domain |

Partners |

|

Sept 2009 |

Wireline Access |

Ericsson |

|

Feb 2010 |

Radio Access Network |

Alcatel-Lucent, Ericsson |

|

April 2010 |

Optical and transport equipment |

Ciena |

|

July 2010 |

IP/MPLS/Ethernet/Evolved Packet Core |

Alcatel-Lucent, Juniper, Cisco |