OFC 2025 industry reflections - Part 2

Gazettabyte is asking industry figures for their thoughts after attending the 50th-anniversary OFC show in San Francisco. In Part 2, the contributions are from BT’s Professor Andrew Lord, Chris Cole, Coherent’s Vipul Bhatt, and Juniper Network’s Dirk van den Borne.ontent

Professor Andrew Lord, Head of Optical Network Research at BT Group

OFC was a highly successful and lively show this year, reflecting a sense of optimism in the optical comms industry. The conference was dominated by the need for optics in data centres to handle the large AI-driven demands. And it was exciting to see the conference at an all-time attendance peak.

From a carrier perspective, I continued to appreciate the maturing of 800-gigabit plugs for core networks and 100GZR plugs (including bidirectional operation for single-fibre working) for the metro-access side.

Hollow-core fibre continues to progress with multiple companies developing products, and evidence for longer lengths of fibre in manufacturing. Though dominated by data centres and low-latency applications such as financial trading, use cases are expected to spread into diverse areas such as subsea cables and 6G xHaul.

There was also a much-increased interest in fibre sensing as an additional revenue generator for telecom operators, although compelling use cases will require more cost-effective technology.

Lastly, there has been another significant increase in quantum technology at OFC. There was an ever-increasing number of Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) protocols on display but with a current focus on Continuous—Variable QKD (CV-QKD), which might be more readily manufacturable and easier to integrate.

Chris Cole, Optical Communications Advisor

For the premier optics conference, the amount of time and floor space devoted to electrical interfaces was astounding.

Even more amazing is that while copper’s death at the merciless hands of optics continues to be reported, the percentage of time devoted to electrical work at OFC is going up. Multiple speakers commented on this throughout the week.

One reason is that as rates increase, the electrical links connecting optical links to ASICs are becoming disproportionately challenging. The traditional Ethernet model of electrical adding a small penalty to the overall link is becoming less valid.

Another reason is the introduction of power-saving interfaces, such as linear and half-retimed, which tightly couple the optical and electrical budgets.

Optics engineers now have to worry about S-parameters and cross-talk of electrical connectors, vias, package balls, copper traces and others.

The biggest buzz in datacom was around co-packaged optics, helped by Nvidia’s switch announcements at GTC in March.

Established companies and start-ups were outbidding each other with claims of the highest bandwidth in the smallest space; typically the more eye-popping the claims, the less actual hard engineering data to back them up. This is for a market that is still approximately zero and faces its toughest hurdles of yield and manufacturability ahead.

To their credit, some companies are playing the long game and doing the slow, hard work to advance the field. For example, I continue to cite Broadcom for publishing extensive characterisation of their co-packaged optics and establishing the bar for what is minimally acceptable for others if they want to claim to be real.

The irony is that, in the meantime, pluggable modules are booming, and it was exciting to see so many suppliers thriving in this space, as demonstrated by the products and traffic in their booths.

The best news for pluggable module suppliers is that if co-packaged optics takes off, it will create more bandwidth demand in the data centre, driving up the need for pluggables.

I may have missed it, but no coherent ZR or other long-range co-packaged optics were announced.

A continued amazement at each OFC is the undying interest and effort in various incarnations of general optical computing.

Despite having no merit as easily shown on first principles, the number of companies and researchers in the field is growing. This is also despite the market holding steady at zero.

The superficiality of the field is best illustrated by a slogan gaining popularity and heard at OFC: computing at the speed of light. This is despite the speed of propagation being similar in copper and optical waveguides. The reported optical computing devices are hundreds of thousands or millions of times larger than equivalent CMOS circuits, resulting in the distance, not the speed, determining the compute time.

Practical optical computing precision is limited to about four bits, unverfied claims of higher precision not withstanding, making it useless in datacenter applications.

Vipul Bhatt, Vice President, Corporate Strategic Marketing at Coherent.

Three things stood out at OFC:

- The emergence of transceivers based on 200-gigabit VCSELs

- A rising entrepreneurial interest in optical circuit switching

- And an accelerated momentum towards 1.6-terabit (8×200-gigabit transceivers) alongside the push for 400-gigabit lanes due to AI-driven bandwidth expansion.

The conversations about co-packaged optics showed increasing maturity, shifting from ‘pluggable versus co-packaged optics’ to their co-existence. The consensus is now more nuanced: co-packaged optics may find its place, especially if it is socketed, while front-panel pluggables will continue to thrive.

Strikingly, talk of optical interconnects beyond 400-gigabit lanes was almost nonexistent. Even as we develop 400 gigabit-per-lane products, we should be planning the next step: either another speed leap (this industry has never disappointed) or, more likely, a shift to ‘fast-and-wide’, blurring the boundary between scale-out and scale-up by using a high radix.

Considering the fast cadence of bandwidth upgrades, the absence of such a pivotal discussion was unexpected.

Dirk van den Borne, director of system engineering at Juniper Networks

The technology singularity is defined as the merger of man and machine. However, after a week at OFC, I will venture a different definition where we call the “AI singularity” the point when we only talk about AI every waking hour and nothing else. The industry seemed close to this point at OFC 2025.

My primary interest at the show was the industry’s progress around 1.6-terabit optics, from scale-up inside the rack to data centre interconnect and long-haul using ZR/ZR+ optics. The industry here is changing and innovating at an incredible pace, driven by the vast opportunity that AI unlocks for companies across the optics ecosystem.

A highlight was the first demos of 1.6-terabit optics using a 3nm CMOS process DSP, which have started to tape out and bring the power consumption down from a scary 30W to a high but workable 25W. Well beyond the power-saving alone, this difference matters a lot in the design of high-density switches and routers.

It’s equally encouraging to see the first module demos with 200 gigabit-per-lane VCSELs and half-retimed linear-retimed optical (LRO) pluggables. Both approaches can potentially reduce the optics power consumption to 20W and below.

The 1.6-terabit ecosystem is rapidly taking shape and will be ready for prime time once 1.6-terabit switch ASICs arrive in the marketplace. There’s still a lot of buzz around linear pluggable optics (LPO) and co-packaged optics, but both don’t seem ready yet. LPO mostly appears to be a case of too little, too late. It wasn’t mature enough to be useful at 800 gigabits, and the technology will be highly challenging for 1.6 terabits.

The dream of co-packaged optics will likely have to wait for two more years, though it does seem inevitable. But with 1.6 terabit pluggable optics maturing quickly, I don’t see it having much impact in this generation.

The ZR/ZR+ coherent optics are also progressing rapidly. Here, 800-gigabit is ready, with proven interoperability between modules and DSPs using the OpenROADM probabilistic constellation shaping standard, a critical piece for interoperability in more demanding applications.

The road to 1600ZR coherent optics for data centre interconnect (DCI) is now better understood, and power consumption projections seem reasonable for 2nm DSP designs.

Unfortunately, the 1600ZR+ is more of a question mark to me, as ongoing standardisation is taking this in a different direction and, hence, a different DSP design from 1600ZR. The most exciting discussions are around “scale-up” and how optics can replace copper for intra-rack connectivity.

This is an area of great debate and speculation, with wildly differing technologies being proposed. However, the goal of around 10 petabit-per-second (Pbps) in cross-sectional bandwidth in a single rack is a terrific industry challenge, one that can spur the development of technologies that might open up new markets for optics well beyond the initial AI cluster application.

ECOC 2023 industry reflections

Gazettabyte is asking industry figures for their thoughts after attending the recent ECOC show in Glasgow. In particular, what developments and trends they noted, what they learned and what, if anything, surprised them. Here are the first responses from BT, Huawei, and Teramount.

Andrew Lord, Senior Manager, Optical Networks and Quantum Research at BT

I was hugely privileged to be the Technical Co-Chair of ECOC in Glasgow, Scotland and have been working on the event for over a year. The overriding impression was that the industry is fully functioning again, post-covid, with a bumper crop of submitted papers and a full exhibition. Chairing the conference left little time to indulge in content. I will need to do my regular ECOC using the playback option. But specific themes struck me as interesting.

There were solid sessions and papers around free space optics, including satellite. The activities here are more intense than we would typically see at ECOC. This reflects a growing interest and the specific expertise within the Scottish research community. Similarly, more quantum-related papers demonstrated how quantum is integrating into the mainstream optical industry.

I was impressed by the progress towards 800-gigabit ZR (800ZR) pluggables in the exhibition. This will make for some interesting future design decisions, mainly if these can be used instead of the increasingly ubiquitous 400 gigabit ZR. I am still unclear whether 800-gigabit coherent can hit the required power consumption points for plugging directly into routers. The costs for these plugs, driven by volumes, will have a significant impact.

I also enjoyed a lively and packed rump session debating the invasion of artificial intelligence (AI) into our industry. I believe considerable care is needed, particularly where AI might have a role in network management and optimisation.

Maxim Kuschnerov, Director R&D at Huawei

ECOC usually has fewer major announcements than the OFC show. But ECOC was full of technical progress this time, making the OFC held in March seem a distant memory.

What was already apparent in September at the CIOE in Shenzhen was on full display on the exhibition floor in Glasgow: the linear drive pluggable optics (LPO) trend has swept everyone off their feet. The performance of 100-gigabit native signalling using LPO can not be ignored for single-mode fibre and VCSELs.

Arista gave a technical deep-dive at the Market Focus with a surprising level of detail that went beyond the usual marketing. There was also a complete switch set-up at the Eoptolink booth, and the OIF interop demonstration.

While we must wait for a significant end user to adopt LPO, it begs the question: is this a one-off technological accident or should the industry embrace this trend and have research set its eyes on 200 gigabits per lane? The latter would require a rearchitecting of today’s switches, a more powerful digital signal processor (DSP) and likely a new forward error corrections (FEC) scheme, making the weak legacy KP4 for the 224-gigabit serdes in the IEEE 802.3dj look like a poor choice.

There was less emphasis on Ethernet 1.6 terabits per second (Tb/s) interfaces with 8x200G optical lanes. However, the arrival of a second DSP source with better performance was noted at the show.

The module power of 1.6-terabit DR8 modules showed no significant technological improvement compared with 800Gbps DSP-based modules and looked even more out of place when benchmarking against 800G LPO pluggables. Arista drove home that we can’t continue increasing the power consumption of the modules at the faceplate despite the 50W QSFP-DD1600 announcement.

The same is true for coherent optics.

Although the demonstration of the first 800ZR live modules was technically impressive, the efficiency of the power per bit hardly improved compared to 400ZR, making the 1600ZR project of OIF look like a tremendous technological challenge.

To explain, a symbol rate of 240 gigabaud (GBd) will drive the optics for 1600ZR. Using 240Gbaud with two levels per symbol to create 16QAM over two dimensions is a 400Gbps net rate or 480Gbps gross rate electrical per lane, albeit very short reach. Coherent has four lanes – 2 polarisations & in-phase and quadrature – to deliver four by 400G or 1.6Tbps. This is like what we have now: 200G on the optical side of 1.6T 8x200G PAM4 and 4x200G on 800ZR, while the electrical (longer reach) host still uses 100 gigabits per lane.

The industry will have to analyse which data centre scenarios direct detection will be able to cover with the same analogue-to-digital & digital-to-analogue converters and how deeply coherent could be driven within the data centre.

ECOC also featured optical access evolution. With the 50G FTTx standard completed with components sampling at the show and products shipping next year, the industry has set its eyes on the next generation of very high-speed PON.

There is some initial agreement on the technological choice for 200 gigabits with a dual-lambda non-return to zero (NRZ) signalling. Much of the industry debate was around the use cases. It is unrealistic to assume that private consumers will continue driving bandwidth demand. Therefore, a stronger focus on 6G wireless fronthaul or enterprise seems a likely scenario for point-to-multi-point technology.

Hesham Taha, CEO of Teramount

Co-packaged optics had renewed vigour in ECOC, thanks partly to the recent announcements of leading foundries and other semiconductor vendors collaborating in silicon photonics.

One crucial issue, though, is that scalable fibre assembly remains an unsolved problem that is getting worse due to the challenging requirements of high-performance systems for AI and high-performance computing. These requirements include a denser “shoreline” with a higher fibre count and a denser fibre pitch, and support for an interposer architecture with different photonic integrated component (PIC) geometries.

Despite customers having different requirements for co-packaged optics fibre assembly, detachable fibres now have wide backing. Having fibre ribbons that can be separated from the co-packaged optics packaging process increases manufacturing yield and reliability. It also allows the costly co-packaged optics-based servers/ switches to be serviced in the field ro replace faulty fibre.

Our company, Teramount, had an ECOC demo showing the availability of such a detachable fibre connector for CPO, dubbed Teraverse.

It is increasingly apparent that the solution for a commercially viable fibre assembly on chip lies with a robust manufacturing ecosystem rather than something tackled by any one system vendor. This fabless model has proven itself in semiconductors and must be extended to silicon photonics. This will allow each part of the production chain – IC designers, foundries, and outsourced semiconductor assembly and test (OSAT) players – to focus on what they do best.

Optical networking's future

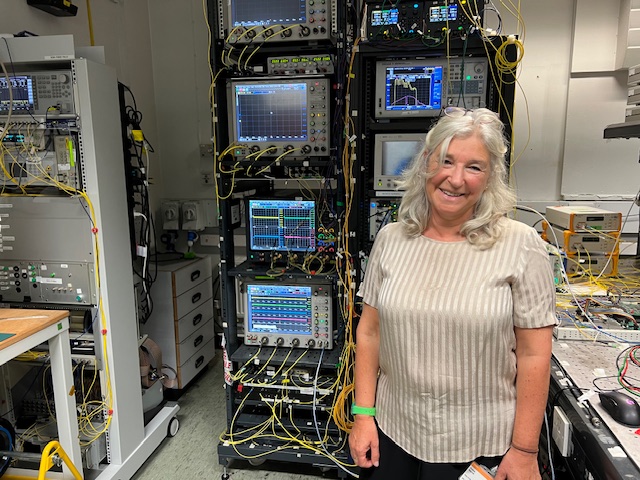

Should the industry do more to support universities undertaking optical networking research? Professor Polina Bayvel thinks so and addressed the issue in her plenary talk at the ECOC conference and exhibition held in Glasgow, Scotland, earlier this month.

In 1994, Bayvel set up the Optical Networks Group at University College London (UCL). Telecom operators and vendors like STC, GPT, and Marconi led optical networking research. However, setting up the UCL’s group proved far-sighted as industry players cut their research budgets or closed.

Universities continue to train researchers, yet firms do not feel a responsibility to contribute to the costs of their training to ensure the flow of talent. One optical systems vendor has hired eight of her team.

In her address, Bayvel outlined how her lab should be compensated. For example, when a club sells a soccer player, the team that developed him should also get part of the fee.

Such income would be welcome, says Bayvel, citing how she has a talented student from Brazil who needs help to fund his university grant. Her lab would also benefit. During a visit, a pile of boxes – state-of-the-art test equipment – had just arrived.

Plenary talk

Bayvel mentioned how the cloud didn’t exist 18 years ago and that what has enabled it is optical networking and Moore’s law. She also tackled how technology will likely evolve in the next 18 years.

Digital data is being created at a remarkable rate, she said. Three exabytes (a billion billion bytes) are being added to the cloud, which holds several zettabytes (1,000 exabytes or ZB) of data. By 2025, data in the cloud will be 275ZB.

The cited stats continued: 6.2 billion kilometres of fibre have been deployed between 2005 and 2023, having 60Zbits of capacity. In comparison, all data satellite systems now deployed offer 100Tb, less than the capacity of one fibre.

Moore’s law has enabled complex coherent digital signal processors (DSPs) that clean up the distortions of an optical signal sent over a fibre. The first coherent DSPs consumed 1W for each gigabit of data sent. Over a decade later, DSPs use 0.1W to send a gigabit.

Data growth will keep driving capacity, says Bayvel. Engineers have had to fight hard to squeeze more capacity using coherent optical technology. Further improvement will come from techniques such as non-linear compensation. One benefit of Moore’s law is that coherent DSPs will be more capable of tasks such as non-linear compensation. For example, Ciena’s latest 3nm CMOS process, the WaveLogic 6e DSP, uses one billion digital logic gates.

Extra wide optical comms

But only so much can be done by the DSP and increasing the symbol rate. The next step will be to ramp the bandwidth by combining a fibre’s O, S, C, L, E and U spectrum bands. New optical devices, such as hybrid amplifiers, will be needed, and pushing transmission distance over these bands will be hard.

“We fought for fractions of a decibel [of signal-to-noise ratio]; surely we’re not going to give up the wavelengths available through this [source of] bandwidth?” said Bayvel.

In his Market Focus talk at ECOC, BT’s Professor Andrew Lord argued the opposite. There will be places where combining the C- and L-bands will make sense, but why bother when spatial division multiplexing fibre deployments in the network are inevitable, he said.

“It is not spatial division multiplexing versus extra wide optical comms; they can co-exist,” said Bayvel.

Bayvel describes work to model the performance of such a large amount of spectrum that has been done in her lab using data collected from the MAREA sub-sea cable. Combining the fibre’s spectral bands – a total of 60 terahertz of spectrum – promises to quadruple the bandwidth currently available. However, this will require more powerful DSPs than are available today.

Another area ripe for development is intelligent optical networking using machine learning.

An ideas lag

Bayvel used her talk to pay tribute to her mentor, Professor John Midwinter.

Midwinter was an optical communications pioneer at BT and then UCL. He headed the team that developed the first trial systems that led to BT becoming the first company in the world to introduce optical fibre communications systems in the network.

In 1983, his last year at BT, Midwinter wrote in the British Telecom Technology Journal that this was the year coherent optical systems would be taken seriously. It took another 20-plus years.

Bayvel noted how many ideas developed in optical research take considerable time before the industry adopts them. “Changes in the network are much slower,” she said. “Operators are conservative and focus on solving today’s problems.”

Another example she cited is Google’s Apollo optical switch being used in its data centres. Bayvel noted that the switch is relatively straightforward, using MEMS technology that has been around for 25 years.

Bayvel used her keynote to attack the telecom regulators.

“It is simply unfair that the infrastructure providers get such a small part of the profits compared to the content providers,” she said. “The regulators have done a terrible job.”

Neil McRae: What’s next for the telecom industry

In a talk at the FutureNet World conference, held in London on May 3-4, Neil McRae explains why he is upbeat about the telecoms industry’s prospects

Neil McRae is tasked with giving the final talk of the two-day FutureNet World conference.

“Yeah, I’m on the graveyard shift,” he quips.

McRae, the former chief network architect at BT, is now chief network strategist at Juniper Network.

The talk’s title is “What’s Next”, McRae’s take on the telecom industry and how it can grow.

McRae starts with how, as a 15-year-old, he had attended an Apple Macintosh computer event at a Novotel Hotel in Hammersmith, London, possibly even this one hosting this conference.

An Apple representative had asked for his feedback as a Macintosh programmer. McRae then listed all the shortfalls programming the PC. Later, he learnt that he had been talking to Steve Jobs.

Perhaps this explains his continual focus on customers and meeting their needs.

What customers care about, says McRae, is ‘new stuff’ that makes a difference in their lives. “Quite often in telecoms, we accidentally change the world without even thinking about it,” he says

McRae cites as an example using FaceTime to watch a newborn grandchild halfway across the world.

“We do it all the time; it is a phenomenal thing about our industry,” says McRae.

The Unvarnished Truth

McRae moves to showing several market and telco survey charts from IDC and Analysys Mason, what he calls ‘The unvarnished truth’.

The first slide shows how the European enterprise communication service market is set to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 3% between 2020 and 2025.

“Three per cent growth, who thinks that is a great business for telcos?” says McRae. “And enterprise is what we are all depending on for big growth and change because [the] consumer [market] is pretty much flat,” says McRae.

Another chart shows similar minimal growth: a forecast that Western Europe’s mobile retail service market will grow from $102 billion in 2016 to $109 billion by 2026. Yet mobile is where the telcos spend a ton of money, he says.

“So, who thinks we should continue doing what we are doing?” McRae asks the audience.

Another forecast showing global fixed and mobile service revenues is marginally better since it includes developing nations that still lack telecommunications services.

In the UK, 95 per cent of the population is on the internet, in Europe it is 84%, says McRae: “The UK is a tough place to be to grow business.”

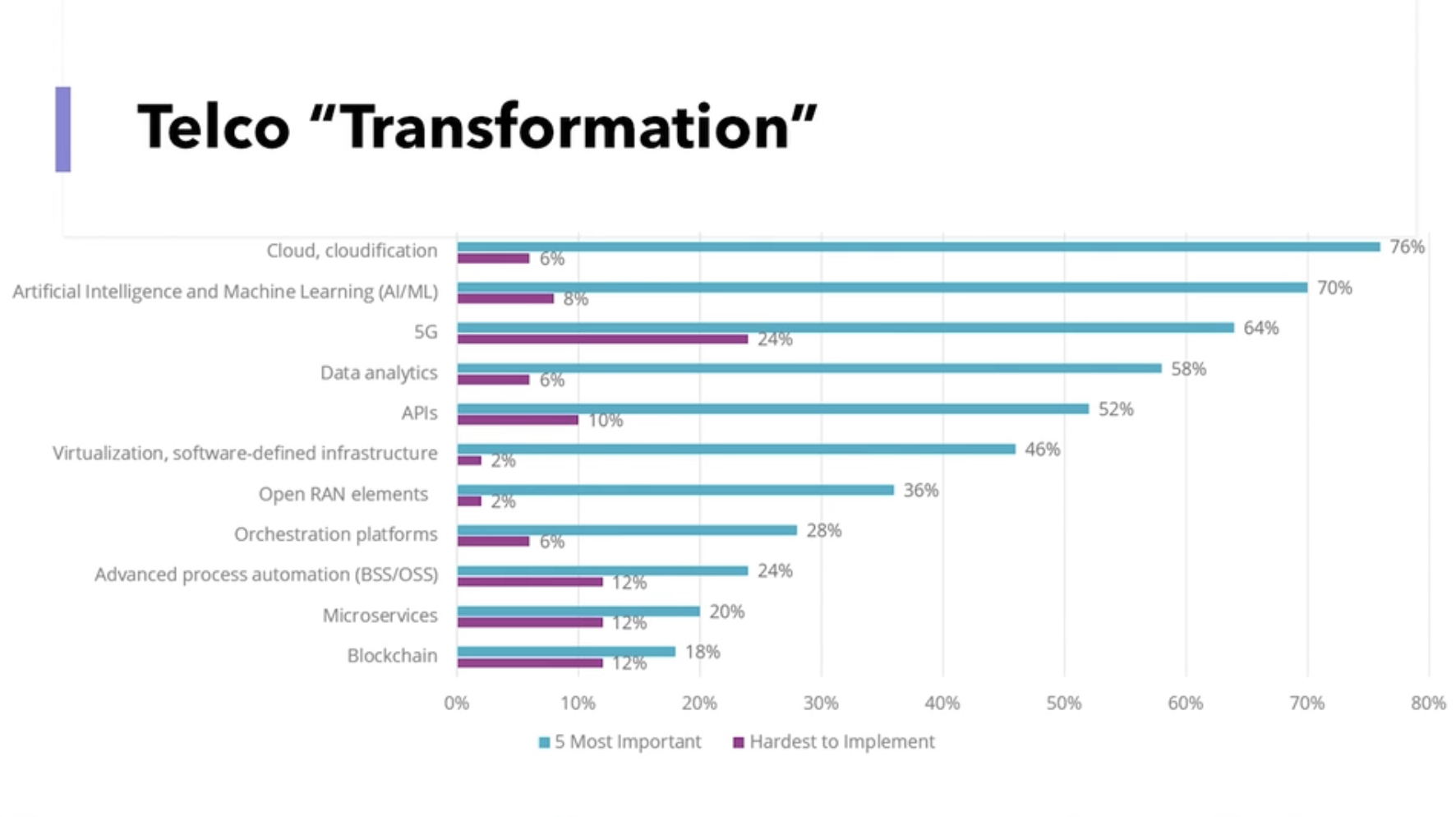

Telco transformation

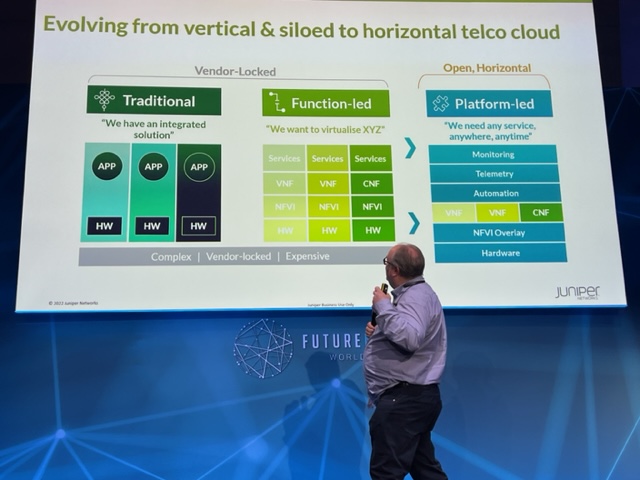

Another slide (see above), the results of a telco survey, shows a list of topics and their impact on telco transformation. McRae asks the audience to respond to those they think will ‘save’ the industry.

He goes through the list: cloud and cloudification, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, 5G, and data analytics. The audience remains muted.

The next item is application programming interfaces (APIs). Again the audience is quiet. “You have been talking about APIs for two days!” says McRae.

“The right APIs,” shouts an audience member. “Ah, yes, the right APIs,” says McRae.

McRae continues down the list, virtualisation and software-defined infrastructure, OpenRAN elements – “not sure what the elements mean” – orchestration platforms, advanced process automation (OSS/BSS), micro-services, and blockchain.

McRae says he has spent the equivalent of a small nation’s budget over his career on OSS and BSS. “Nothing is automated, and I can’t get the data I need,” he says.

McRae gives his view. He believes the cloud will help telcos, but what most excites him is AI and machine learning, and data analytics.

“Learning the insights the data tells us and using them, putting a pound sign on them,” says McRae. “We have done some of that, but there is much more to do.”

He puts up a second survey showing the priorities of European operators: customer experience and increasing operational agility.

“Finally, after years, telcos realise that customers are important,” he says.

Opportunities

The survey also highlights the telcos’ belief that they can deliver solutions for industries and enterprise customers.

“This is a massive opportunity for telcos that allows us to grow revenues, create cool technology and hire amazing engineers,” says McRae.

The transformation needed in telecoms is about customers and taking risks with customers, he says.

One opportunity is digitalisation. McRae points outs that digitalisation is a process that never stops.

The three leading Chinese operators are keenly pursuing what they call industrial digitalisation or industrial internet. For China Telecom, industrial digitalisation now accounts for a quarter of its service revenues.

“Today, it is about cloud, cloud technologies, and smartphones, but tomorrow it could be about wearables or technology that is tracking what you are doing and making your life easier,” says McRae.

Digitalisation is an expertise that the telecom industry is not putting enough effort into, he says: “And as telcos, we have a massive right to play here.”

Another opportunity is AI and data, learning from the insights present in data to grow revenue.

“We have more data than most organisations, we haven’t used it very well, and we can build upon it,” says McRae, adding that AI needs the network to be valuable and improve our lives.

With data and AI, trust is vital. “If we are not trusted as an industry, we are dead,” says McRae. But because telcos are trusted entities, they can help other organisations improve trustworthiness.

Another opportunity is using the network for humans to interact in advanced ways. Since telecoms is a resource-heavy industry, such network-aided interaction would be immediately beneficial.

For this, what is needed is a cloud-native platform that integrates well with the network, and cloud platforms are generally poorly integrated with the network, he says.

He ends his talk by returning to customers and what they want: customers expect networks and services to be always present.

This explains the telcos’ continual marginal growth, he says: “The reason we have this is because there is a big chunk of customers’ lives where they can’t rely upon the network.”

Different thinking is needed if the network is to grow beyond the smartphone. Population coverage is not enough; what is needed is total coverage.

“Wherever I am, I want to use my device, to be connected, for the things that I don’t even know is doing stuff to be able to do them without worrying about connectivity,” he says.

And that is why 6G must be about 100 per cent connectivity,” says McRae: “Either we can do it, or someone else is going to.”

With that, FutureNet comes to ends, and McRae quickly departs to embark on the next chapter in his career. `

Neil McRae will be one of the speakers at the DSP Leaders World Forum, May 23-24, 2023.

Deutsche Telekom explains its IP-over-DWDM thinking

Telecom operators are always seeking better ways to run their networks. In particular, operators regularly scrutinise how best to couple the IP layer with their optical networking infrastructure.

The advent of 400-gigabit coherent modules that plug directly into an IP router is one development that has caught their eye.

Placing dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) interfaces directly onto an IP router allows the removal of a separate transponder box and its interfacing.

IP-over-DWDM is not a new concept. However, until now, operators have had to add a coherent line card, taking up valuable router chassis space.

Now, with the advent of compact 400-gigabit coherent pluggables developed for the hyperscalers to link their data centres, telecom operators have realised that such pluggables also serve their needs.

BT will start rolling out IP-over-DWDM in its network this year, while Deutsche Telekom has analysed the merits of IP-over-DWDM.

“The adoption of IP-over-DWDM is the subject of our techno-economical studies,” says Werner Weiershausen, senior architect for the transport network at Deutsche Telekom.

Network architecture

Deutsche Telekom’s domestic network architecture comprises 12 large nodes where IP and OTN backbones align with the underlying optical networking infrastructure. These large nodes – points of presence – can be over 1,000km apart.

Like many operators, Deutsche Telekom has experienced IP annual traffic growth of 35 per cent. The need to carry more traffic without increasing costs has led the operators to adopt coherent technology, with the symbol rate rising with each new generation of optical transport technology.

A higher channel bit rate sends more data over an optical wavelength. The challenge, says Weiershausen, is maintaining the long-distance reaches with each channel rate hike.

Deutsche Telekom’s in-house team forecasts that IP traffic growth will slow down to a 20 per cent annual growth rate and even 16 per cent in future.

Weiershausen says this is still to be proven but that if annual traffic growth does slow down to 16-20 per cent, bandwidth growth issues will remain; it is just that they can be addressed over a longer timeframe.

Bandwidth and reach are long-haul networking issues. Deutsche Telekom’s metro networks, which are horse-shoe-shaped, have limited spans overall.

“For metro, our main concern is to have the lowest cost-per-bit because we are fibre- and spectrum-rich, and even a single DWDM fibre pair per metro horseshoe ring offer enough bandwidth headroom,” says Weiershausen. “So it’s easy; we have no capacity problem like the backbone. Also there, we are fibre-rich but can avoid the costly activation of multiple parallel fibre trunks.”

IP-over-DWDM

IP-over-DWDM is increasingly associated with adding pluggable optics onto an IP core router.

“This is what people call IP-over-DWDM, or what Cisco calls it hop-by-hop approach,” says Dr Sascha Vorbeck, head of strategy and architecture IP-core & transport networks at Deutsche Telekom.

Cisco’s routed optical networking – its term for the hop-by-hop approach – uses the optical layer for point-to-point connections between IP routers. As a result, traffic switching and routing occur at the IP layer rather than the optical layer, where optical traffic bypass is performed using reconfigurable optical add/drop multiplexers (ROADMs).

Routed optical networking also addresses the challenge of the rising symbol rate of coherent technology, which must maintain the longest reaches when passing through multiple ROADM stages.

Deutsche Telekom says it will not change its 12-node backbone network to accommodate additional routing stages.

“We will not change our infrastructure fundamentally because this is costly,” says Weiershausen. “We try to address this bandwidth growth with technology and not with the infrastructure change.”

Deutsche Telekom’s total cost-of-ownership analysis highlights that optical bypass remains attractive compared to a hop-by-hop approach for specific routes.

However, the operator has concluded that the best approach is to have both: some hop-by-hop where it suits its network in terms of distances but also using optical bypass for longer links using either ROADM or static bypass technology.

“A mixture is the optimum from our total cost of ownership calculation,” says Weiershausen. “There was no clear winner.”

Strategy

Deutsche Telecom favours coherent interfaces on its routers for its network backbone because it wants to simplify its network. In addition, the operator wants to rid its network of existing DWDM transponders and their short reach – ‘grey’ – interfaces linking the IP router to the DWDM transponder box.

“They use extra power and are an extra capex [capital expenditure] cost,” says Weiershausen. “They are also an additional source of failures when you have in-line several network elements. That said, heat dissipation of long-reach coherent optical DWDM interfaces limited the available IP router interfaces that could have been activated in the past.

For example, a decade ago, Deutsche Telecom tried to use IP-over-DWDM for its backbone network but had to step back to use an external DWDM transponder box due to heat dissipation problems.

The situation may have changed with modern router and optical interface generations, but this is under further study by Deutsche Telecom and is an essential prerequisite for its evolution roadmap.

Deutsche Telecom is still using traditional DWDM equipment between the interconnection of IP routers with grey interfaces. Deutsche Telecom undertook an evaluation in 2020 and calculated a traditional DWDM network versus a hop-by-hop approach. Then, the hop-by-hop method was 20 per cent more expensive. Deutsche Telecom plans to redo the calculations to see if anything has changed.

The operator has yet to decide whether to adopt ZR+ coherent pluggable optics and a hop-by-hop approach or use more advanced larger coherent modules in its routers. “This is not decided yet and depends on pricing evolution,” says Weiershausen.

With the volumes expected for pluggable coherent optics, the expectation is they will have a notable price advantage compared to traditional high-performance coherent interfaces.

But Deutsche Telekom is still determining, believing that conventional coherent interfaces may also come down markedly in price.

SDN controller

Another issue for consideration with IP-over-DWDM is the software-defined networking (SDN) controller.

IP router vendors offer their SDN controllers, but there also is a need for working with third-party SDN controllers.

For example, Deutsche Telekom is a member of the OpenROADM multi-source agreement and has pushed for IP-over-DWDM to be a significant application of the MSA.

But there are disaggregation issues regarding how a router’s coherent optical interfaces are controlled. For example, are the optical interfaces overseen and orchestrated by the OpenROADM SDN controller and its application programming interface (API) or is the SDN controller of each IP router vendor responsible for steering the interfaces?

Deutsche Telekom says that a compromise has been reached for the OpenROADM MSA whereby the IP router vendors’ SDN controllers oversee the optics but that for the solution to work, information is exchanged with the OpenROADM’s SDN controller.

“That way, the path computation engine (PCE) of the optical network layer, including the ROADMs, can calculate the right path to network the traffic. “Without information from the IP router, it would be blind; it would not work,” says Weiershausen.

Automation

Weiershausen says it is not straightforward to say which approach – IP-over-DWDM or a boundary between the IP and optical layers – is easier to automate.

“Principally, it is the same in terms of the information model; it is just that there are different connectivity and other functionalities [with the two approaches],” says Weiershausen.

But one advantage of a clear demarcation between the layers is the decoupling of the lifecycles of the different equipment.

Fibre has the longest lifecycle, followed by the optical line system, with IP routers having the shortest of the three, with new generation equipment launched every few years.

Decoupling and demarcation is therefore a good strategy here, notes Weiershausen.

BT's IP-over-DWDM move

- BT will roll out next year IP-over-DWDM using pluggable coherent optics in its network

- At ECOC 2022, BT detailed network trials that involved the use of ZR+ and XR optics coherent pluggable modules

Telecom operators have been reassessing IP-over-DWDM with the advent of 400-gigabit coherent optics that plug directly into IP routers.

According to BT, using pluggables for IP-over-DWDM means a separate transponder box and associated ‘grey’ (short-reach) optics are no longer needed.

Until now, the transponder has linked the IP router to the dense wavelength-division multiplexing (DWDM) optical line system.

“Here is an opportunity to eliminate unnecessary equipment by putting coloured optics straight onto the router,” says Professor Andrew Lord, BT’s head of optical networking.

Removing equipment saves power and floor space too.

DWDM trends

Operators need to reduce the cost of sending traffic, the cost-per-bit, given the continual growth of IP traffic in their networks.

BT says its network traffic is growing at 30 per cent a year. As a result, the operator is starting to see the limits of its 100-gigabit deployments and says 400-gigabit wavelengths will be the next capacity hike.

Spectral efficiency is another DWDM issue. In the last 20 years, BT has increased capacity by lighting a new fibre pair using upgraded optical transport equipment.

Wavelength speeds have gone from 2.5 to 10, then to 40, 100, and soon 400 gigabits, each time increasing the total traffic sent over a fibre pair. But that is coming to an end, says BT.

“If you go to 1.2 terabits, it won’t go as far, so something has to give,” says Lord. ”So that is a new question we haven’t had to answer before, and we are looking into it.”

Fibre capacity is no longer increasing because coherent optical systems are already approaching the Shannon limit; send more data on a wavelength and it occupies a wider channel bandwidth.

Optical engineers have improved transmission speeds by using higher symbol rates. Effectively, this enables more data to be sent using the same modulation scheme. And keeping the same modulation scheme means existing reaches can still be met. However, upping the symbol rate is increasingly challenging.

Other ways of boosting capacity include making use of more spectral bands of a fibre: the C-band and the L-band, for example. BT is also researching spatial division multiplexing (SDM) schemes.

IP-over-DWDM

IP-over-DWDM is not a new topic, says BT. To date, IP-over-DWDM has required bespoke router coherent cards that take an entire chassis slot, or the use of coherent pluggable modules that are larger than standard QSFP-DD client-side optics ports.

“That would affect the port density of the router to the point where it’s not making the best use of your router chassis,“ says Paul Wright, optical research manager at BT Labs.

The advent of OIF-defined 400ZR optics has catalysed operators to reassess IP-over-DWDM.

The 400ZR standard was developed to link equipment housed in separate data centres up to 120km apart. The 120km reach is limiting for operators but BT’s interest in ZR optics stems from the promise of low-cost, high-volume 400-gigabit coherent optics.

“It [400ZR optics] doesn’t go very far, so it completely changes our architecture,” says Lord. “But then there’s a balance between the numbers of [router] hops and the cost reduction of these components.”

BT modelled different network architectures to understand the cost savings using coherent ZR and ZR+ optics; ZR+ pluggables have superior optical performance compared to 400ZR.

The networks modelled included IP routers in a hop-by-hop architecture where the optical layer is used for point-to-point links between the routers.

This worked well for traffic coming into a hub site but wasn’t effective when traffic growth occurred across the network, says Wright, since traffic cascaded through every hop.

BT also modelled ZR+ optics in a reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexer (ROADM) network architecture, as well as a hybrid arrangement using both ZR+ and traditional coherent optics. Traditional coherent optics, with its superior optical performance, can pass through a string of ROADM stages where ZR+ optics falls short.

BT compared the cost of the architectures assuming certain reaches for the various coherent optics and published the results in a paper presented at ECOC 2020. The study concluded that ZR and ZR+ optics offer significant cost savings compared to coherent transponders.

ZR+ pluggables have since improved, using higher output powers to better traverse a network’s ROADM stages. “The [latest] ZR+ optics should be able to go further than we predicted,” says Wright.

It means BT is now bought into IP-over-DWDM using pluggable optics.

BT is doing integration tests and plans to roll out the technology sometime next year, says Lord.

XR optics

BT is a member of the Open XR Forum, promoting coherent optics technology that uses optical sub-carriers.

Dubbed XR optics, if all the subs-carriers originate at the same point and are sent to a common destination, the technology implements a point-to-point communication scheme.

Sub-carrier technology also enables traffic aggregation. Each sub-carrier, or a group of sub-carriers, can be sent from separate edge-network locations to a hub where they are aggregated. For example, 16 endpoints, each using a 25-gigabit sub-carrier, can be aggregated at a hub using a 400-gigabit XR optics pluggable module. Here, XR optics is implementing point-to-multipoint communication.

Lord views XR optics as innovative. “If only we could find a way to use it, it could be very powerful,” he says. “But that is not a given; for some applications, XR optics might be too big and for others it may be slightly too small.”

ECOC 2022

BT’s Wright shared the results of recent trial work using ZR+ and XR optics at the recent ECOC 2022 conference, held in Basel in September.

The 400ZR+ were plugged into Nokia 7750 SR-s routers for an IP-over-DWDM trial that included the traffic being carried over a third-party ROADM system in BT’s network. BT showed the -10dBm launch-power ZR+ optics working over the ROADM link.

For Wright, the work confirms that 0dBm launch-power ZR+ optics will be important for network operators when used with ROADM infrastructures.

BT also trialled XR optics where traffic flows were aggregated.

“These emerging technologies [ZR+ and XR optics] open up for the first time the ability to deploy a full IP-over-DWDM solution,” concluded Wright.

ECOC '22 Reflections - Part 3

Gazettabyte is asking industry and academic figures for their thoughts after attending ECOC 2022, held in Basel, Switzerland. In particular, what developments and trends they noted, what they learned, and what, if anything, surprised them.

In Part 3, BT’s Professor Andrew Lord, Scintil Photonics’ Sylvie Menezo, Intel’s Scott Schube, and Quintessent’s Alan Liu share their thoughts.

Professor Andrew Lord, Senior Manager of Optical Networks Research, BT

There was strong attendance and a real buzz about this year’s show. It was great to meet face-to-face with fellow researchers and learn about the exciting innovations across the optical communications industry.

The clear standouts of the conference were photonic integrated circuits (PICs) and ZR+ optics.

PICs are an exciting piece of technology; they need a killer use case. There was a lot of progress and discussion on the topic, including an energetic Rump session hosted by Jose Pozo, CTO at Optica.

However, there is still an open question about what use cases will command volumes approaching 100,000 units, a critical milestone for mass adoption. PICs will be a key area to watch for me.

We’re also getting more clarity on the benefits of ZR+ for carriers, with transport through existing reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexer (ROADM) infrastructures. Well done to the industry for getting to this point.

All in all, ECOC 2022 was a great success. As one of the Technical Programme Committee (TPC) Chairs for ECOC 2023 in Glasgow, we are already building on the great show in Basel. I look forward to seeing everyone again in Glasgow next year.

Sylvie Menezo, CEO of Scintil Photonics

What developments and trends did I note at ECOC? There is a lot of development work on emergent hybrid modulators.

Scott Schube, Senior Director of Strategic Marketing and Business Development, Silicon Photonics Products Division at Intel.

There were not a huge amount of disruptive announcements at the show. I expect the OFC 2023 event will have more, particularly around 200 gigabit-per-lane direct-detect optics.

Several optics vendors showed progress on 800 gigabit/ 2×400 gigabit optical transceiver development. There are now more vendors, more flavours and more components.

Generalising a bit, 800 gigabit seems to be one case where the optics are ready ahead of time, certainly ahead of the market volume ramp.

There may be common-sense lessons from this, such as the benefits of technology reuse, that the industry can take into discussions about the next generation of optics.

Alan Liu, CEO of Quintessent

Several talks focused on the need for high wavelength count dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) optics in emerging use cases such as artificial intelligence/ machine learning interconnects.

Intel and Nvidia shared their vision for DWDM silicon photonics-based optical I/O. Chris Cole discussed the CW-WDM MSA on the show floor, looking past the current Ethernet roadmap at finer DWDM wavelength grids for such applications. Ayar Labs/Sivers had a DFB array DWDM light source demo, and we saw impressive research from Professor Keren Bergman’s group.

An ecosystem is coalescing around this area, with a healthy portfolio and pipeline of solutions being innovated on by multiple parties, including Quintessent.

The heterogeneous integration workshop was standing room only despite being the first session on a Sunday morning.

In particular, heterogeneously integrated silicon photonics at the foundry level was an emergent theme as we heard updates from Tower, Intel, imec, and X-Celeprint, among other great talks. DARPA has played – and plays – a key role in seeding the technology development and was also present to review such efforts.

Fibre-attach solutions are an area to watch, in particular for dense applications requiring a high number of fibres per chip. There is some interesting innovation in this area, such as from Teramount and Suss Micro-Optics among others.

Shortly after ECOC, Intel also showcased a pluggable fibre attach solution for co-packaged optics.

Reducing the fibre packaging challenge is another reason to employ higher wavelength count architectures and DWDM to reduce the number of fibres needed for a given aggregate bandwidth.

BT’s first quantum key distribution network

The trial of a commercial quantum-secured metro network has started in London.

The BT network enables customers to send data securely between sites by first sending encryption keys over optical fibre using a technique known as quantum key distribution (QKD).

The attraction of QKD is that any attempt to eavesdrop and intercept the keys being sent is discernable at the receiver.

The network uses QKD equipment and key management software from Toshiba while the trial also involves EY, the professional services company.

EY is using BT’s network to connect two of its London sites and will showcase the merits of QKD to its customers.

London’s quantum network

BT has been trialling QKD for data security for several years. It had announced a QKD trial in Bristol in the U.K. that uses a point-to-point system linking two businesses.

BT and Toshiba announced last October that they were expanding their QKD work to create a metro network. This is the London network that is now being trialled with customers.

Building a quantum-secure network is a different proposition from creating point-to-point links.

“You can’t build a network with millions of separate point-to-point links,” says Professor Andrew Lord, BT’s head of optical network research. “At some point, you have to do some network efficiency otherwise you just can’t afford to build it.”

BT says quantum security may start with bespoke point-to-point links required by early customers but to scale a secure quantum network, a common pipe is needed to carry all of the traffic for customers using the service. BT’s commercial quantum network, which it claims is a world-first, does just that.

“We’ve got nodes in London, three of them, and we will have quantum services coming into them from different directions,” says Lord.

Not only do the physical resources need to be shared but there are management issues regarding the keys. “How does the key management share out those resources to where they’re needed; potentially even dynamically?” says Lord.

He describes the London metro network as QKD nodes with links between them.

One node connects Canary Wharf, London‘s financial district. Another node is in the centre of London for mainstream businesses while the third node is in Slough to serve the data centre community.

“We’re looking at everything really,” says Lord. “But we’d love to engage the data centre side, the financial side – those two are really interesting to us.”

Customers’ requirements will also differ; one might want a quantum-protected Ethernet service while another may only want the network to provide them with keys.

“We have a kind of heterogeneous network that we’re starting to build here, where each customer is likely to be slightly different,” says Lord.

QKD and post-quantum algorithms

QKD uses physics principles to secure data but cryptographic techniques also being developed are based on clever maths to make data secure, even against powerful future quantum computers.

Such quantum-resistant public-key cryptographic techniques are being evaluated and standardised by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

BT says it plans to also use such quantum-resistant techniques and are part of its security roadmap.

“We need to look at both the NIST algorithms and the key QKD ones,” says Lord. “Both need to be developed and to be understood in a commercial environment.“

Lord points out that the encryption products that will come out of the NIST work are not yet available. BT also has plenty of fibre, he says, which can be used not just for data transmission but also for security.

He also points out that the maths-based techniques will likely become available as freeware. “You could, if you have the skills, implement them yourself completely freely,” says Lord. “So the guys that make crypto kits using these maths techniques, how do they make money?”

Also, can a user be sure that those protocols are secure? “How do you know that there isn’t a backdoor into those algorithms?” says Lord. “There’s always this niggling doubt.”

BT says the post-quantum techniques are valuable and their use does not preclude using QKD.

Satellite QKD

Satellites can also be used for QKD.

Indeed, BT has an agreement with UK start-up Arqit which is developing satellite QKD technology whereby BT has exclusive rights to distribute and market quantum keys in the UK and to UK multinationals.

BT says satellite and fibre will both play a role, the question is how much of each will be used.

“They work well together but the fibre is not going to go across oceans, it’s going to be very difficult to do that,” says Lord. “And satellite does that very well.”

However, satellite QKD will struggle to provide dense coverage.

“If you think of a low earth orbit satellite coming overhead, it’s only gonna be able to lock onto to one ground station at a time, and then it’s gone somewhere else around the world,” says Lord. More satellites can be added but that is expensive.

He expects that a small number of satellite-based ground stations will be used to pick up keys at strategic points. Regional key distribution will then be used, based on fibre, with a reach of up to 100km.

“You can see a way in which satellite the fibre solutions come together,” says Lord, the exact balance being determined by economics.

Hollow-core fibre

BT says hollow-core fibre is also attractive for QKD since the hollowness of the optical fibre’s core avoids unwanted interaction between data transmissions and the QKD.

With hollow-core, light carrying regular data doesn’t interact with the quantum light operating at a different wavelength whereas it does for standard fibre that has a solid glass core.

“The glass itself is a mechanism that gets any photons talking to each other and that’s not good,” says Lord. “Particularly, it causes Raman scattering, a nonlinear process in glass, where light, if it’s got enough power, creates a lot of different wavelengths.”

In experiments using standard fibre carrying classical and quantum data, BT has had to turn down the power of the data signal to avoid the Raman effect and ensure the quantum path works.

Classical data generate noise photons that get into the quantum channel and that can’t be avoided. Moreover, filtering doesn’t work because the photons can’t be distinguished. It means the resulting noise stops the QKD system from working.

In contrast, with hollow-core fibre, there is no Raman effect and the classical data signal’s power can be ramped to normal transmission levels.

Another often-cited benefit of hollow-core fibre is its low latency performance. But for QKD that is not an issue: the keys are distributed first and the encryption may happen seconds or even minutes later.

But hollow-core fibre doesn’t just offer low latency, it offers tightly-controlled latency. With standard fibre the latency ‘wiggles around’ a lot due to the temperature of the fibre and pressure. But with a hollow core, such jitter is 20x less and this can be exploited when sending photons.

“As time goes on with the building of quantum networks, timing is going to become increasingly important because you want to know when your photons are due to arrive,” says Lord.

If a photon is expected, the detector can be opened just before its arrival. Detectors are sensitive and the longer they are open, the more likely they are to take in unwanted light.

“Once they’ve taken something in that’s rubbish, you have to reset them and start again,” he says. “And you have to tidy it all up before you can get ready for the next one. This is how these things work.“

The longer that detector can be kept closed, the better it performs when it is opened. It also means a higher key rate becomes possible.

“Ultimately, you’re going to need much better synchronisation and much better predictability in the fibre,” says Lord. “That’s another reason why I like hollow-core fibre for QKD.”

Quantum networks

“People focussed on just trying to build a QKD service, miss the point; that’s not going to be enough in itself,” says Lord. “This is a much longer journey towards building quantum networks.”

BT sees building quantum small-scale QKD networks as the first step towards something much bigger. And it is not just BT. There is the Innovate UK programme in the UK. There are also key European, US and China initiatives.

“All of these big nation-states and continents are heading towards a kind of Stage I, building a QKD link or a QKD network but that will take them to bigger things such as building a quantum network where you are now distributing quantum things.”

This will also include connecting quantum computers.

Lord says different types of quantum computers are emerging and no one yet knows which one is going to win. He believes all will be employed for different kinds of use cases.

“In the future, there will be a broad range of geographically scattered quantum computing resources, as well as classical compute resources,” says Lord. “That is a future internet.”

To connect such quantum computers, quantum information will need to be exchanged between them.

Lord says BT is working with quantum computing experts in the UK to determine what the capabilities of quantum computers are and what they are good at solving. It is classifying quantum computing capabilities into the different categories and matching them with problems BT has.

“In some cases, there’s a good match, in some cases, there isn’t,” says Lord. “So we try to extrapolate from that to say, well, what would our customers want to do with these and it’s a work in progress.”

Lord says it is still early days concerning quantum computing. But he expects quantum resources to sit alongside classical computing with quantum computers being used as required.

“Customers probably won’t use it for very long; maybe buying a few seconds on a quantum computer might be enough for them to run the algorithm that they need,” he says. In effect, quantum computing will eventually be another accelerator alongside classical computing.

”You already can buy time by the second on things like D-Wave Systems’ quantum computers, and you may think, well, how is that useful?” says Lord. “But you can do an awful lot in that time on a quantum computer.”

Lord already spends a third of his working week on quantum.

“It’s such a big growing subject, we need to invest time in it,” says Lord.

BT’s Open RAN trial: A mix of excitement and pragmatism

“We in telecoms, we don’t do complexity very well.” So says Neil McRae, BT’s managing director and chief architect.

He was talking about the trend of making network architectures open and in particular the Open Radio Access Network (Open RAN), an approach that BT is trialling.

“In networking, we are naturally sceptical because these networks are very important and every day become more important,” says McRae

Whether it is Open RAN or any other technology, it is key for BT to understand its aims and how it helps. “And most importantly, what it means for customers,” says McRae. “I would argue we don’t do enough of that in our industry.”

Open RAN

Open RAN has become a key focus in the development of 5G. Open RAN is backed by leading operators, it promises greater vendor choice and helps counter the dependency on the handful of key RAN vendors such as Nokia and Ericsson. There are also geopolitical considerations given that Huawei is no longer a network supplier in certain countries.

“Huawei and China, once they were the flavour of the month and now they no longer are,” says McRae. “That has driven a lot of concern – there are only Nokia and Ericsson as scaled players – and I think that is a thing we need to worry about.”

McRae points out that Open RAN is an interface standard rather than a technology.

“Those creating Open RAN solutions, the only part that is open is that interface side,” he says. ”If you think of Nokia, Ericsson, Mavenir, Rakuten and Altiostar – any of the guys building this technology – none of their technology is specifically open but you can talk to it via this open interface.”

Opportunity

McRae is upbeat about Open RAN but much work is needed to realise its potential.

“Open RAN, and I would probably say the same about NFV (network functions virtualisation), has got a lot of momentum and a lot of hype well before I think it deserves it,” he says.

Neil McRaeBT favours open architectures and interoperability. “Why wouldn’t we want to to be part of that, part of Open RAN,” says McRae. “But what we are seeing here is people excited about the potential – we are hugely excited about the potential – but are we there yet? Absolutely not.”

BT views Open RAN as a way to support the small-cell neutral host model whereby a company can offer operators coverage, one way Open RAN can augment macro cell coverage.

Open RAN can also be used to provide indoor coverage such as in stadiums and shopping centres. McRae says Open RAN could also be used for transportation but there are still some challenges there.

“We see Open RAN and the Open RAN interface specifications as a great way for building innovation into the radio network,” he says. “If there is one part that we are hugely excited about, it is that.”

BT’s Open RAN trial

BT is conducting an Open RAN trial with Nokia in Hull, UK.

“We haven’t just been working with Nokia on this piece of work, other similar experiments are going on with others,” says McRae.

McRae equates Open RAN with software-defined networking (SDN). SDN uses several devices that are largely unintelligent while a central controller – ’the big brain’ – controls the devices and in the process makes them more valuable.

“SDN has this notion of a controller and devices and the Open RAN solution is no different: it uses a different interface but it is largely the same concept,” says McRae.

This central controller in Open RAN is the RAN Intelligent Controller (RIC) and it is this component that is at the core of the Nokia trial.

“That controller allows us to deploy solutions and applications into the network in a really simple and manageable way,” says McRae.

The RIC architecture is composed of a near-real-time RIC that is very close to the radio and that makes almost instantaneous changes based on the current situation.

There is also a non-real-time controller – that is used for such tasks as setting policy, the overall run cycle for the network, configuration and troubleshooting.

“You kind of create and deploy it, adjust it or add or remove things, not in real-time,” says McRae. “It is like with a train track, you change the signalling from red to green long before the train arrives.”

BT views the non-real-time aspect of the RIC as a new way for telcos to automate and optimise the core aspects of radio networking.

McRae says the South Bank, London is one of the busiest parts of BT’s network and the operator has had to keep adding spectrum to the macrocells there.

“It is getting to the point where the macro isn’t going to be precise enough to continue to build a great experience in a location like that,” he says.

One solution is to add small cells and BT has looked at that but has concluded that making macros and small cells work together well is not straightforward. This is where the RIC can optimise the macro and small cells in a way that improves the experience for customers even when the macro equipment is from one vendor and the small cells from another.

“The RIC allows us to build solutions that take the demand and the requirements of the network a huge step forward,” he says. “The RIC makes a massive step – one of the biggest steps in the last decade, probably since massive MIMO – in ensuring we can get the most out of our radio network.”

BT is focussed on the non-real-time RIC for the initial use cases it is trialling. It is using Nokia’s equipment for the Hull trial.

BT is also testing applications such as load optimisation between different layers of the network and between different neighbouring sites. Also where there is a failure in the network it is using ‘Xapps’ to reroute traffic or re-optimise the network.

Nokia also has AI and machine learning software which BT is trialling. BT sees AI and machine learning-based solutions as a must as ultimately human operators are too slow.

Trial goals

BT wants to understand how Open RAN works in deployment. For example, how to manage a cell that is part of a RIC cluster.

In a national network, there will likely be multiple RICs used.

“We expect that this will be a distributed architecture,” says McRae. “How do you control that? Well, that’s where the non-real-time RIC has a job to do, effectively to configure the near-real-time RIC, or RICs as we understand more about how many of them we need.”

Another aspect of the trial is to see if, by using Open RAN, the network performance KPIs can be improved. These include time on 4G/ time on 5G, and the number of handovers and dropped calls.

“Our hope and we expect that all of these get better; the early signs in our labs are that they should all get better, the network should perform more effectively,” he says.

BT will also do coverage testing which, with some of the newer radios it is deploying, it expects to improve.

“We’ve done a lot of learning in the lab,” says McRae. “Our experience suggests that translating that into operational knowledge is not perfect. So we’re doing this to learn more about how this will work and how it will benefit customers at the end of the day.”

Openness and diversity

Given that Open RAN aims to open vendor choice, some have questioned whether BT’s trial with Nokia is in the spirit of the initiative.

“We are using the Open RAN architecture and the Open RAN interface specs,” says McRae. “Now, for a lot of people, Open RAN means you have got to have 12 vendors in the network. Let me tell you, good luck to everyone that tries that.”

BT says there are a set of flavours of Open RAN appearing. One is Rakuten and Symphony, another is Mavenir. These are end-to-end solutions being built that can be offered to operators as a solution.

“Service providers are terrible at integrating things; it is not our core competency,” says McRae. “We have got better over the years but we want to buy a solution that is tested, that has a set of KPIs around how it operates, that has all the security features we need.”

This is key for a platform that in BT’s case serves 30 million users. As McRae puts it, if Open RAN becomes too complicated, it is not going to get off the ground: “So we welcome partnerships, or ecosystems that are forming because we think that is going to make Open RAN more accessible.”

McRae says some of the reaction to its working with Nokia is about driving vendor diversity.

BT wants diverse vendors that can provide it with greater choice and benefit from competition. But McRae points out that many of the vendors’ equipment use the same key components from a handful of chip companies; and chips that are made in two key locations.

“What we want to see is those underlying components, we want to see dozens of companies building them all over the world,” he says. “They are so crucial to everything we do in life today, not just in the network, but in your car, smartphone, TV and the microwave.”

And while more of the network is being implemented in software – BT’s 5G core is all software – hardware is still key where there are are packet or traffic flows.

“The challenge in some of these components, particularly in the radio ecosystem, is you need strong parallel processing,” says McRae. “In software that is really difficult to do.”

“Intel, AMD, Broadcom and Qualcomm are all great partners,“ says McRae. “But if any one of these guys, for some reason, doesn’t move the innovation curve in the way we need it to move, then we run into real problems of how to grow and develop the network.”

What BT wants is as much IC choice as possible, but how that will be achieved McRae is less certain. But operators rightly have to be concerned about it, he says.

Can a think tank tackle telecoms innovation deficit?

The Telecom Ecosystem Group (TEG) will publish shortly its final paper that concludes two years of industry discussion on ways to spur innovation in telecommunications.

The paper, entitled Addressing the Telecom Innovation Deficit, says telcos have lost much of their influence in shaping the technologies on which they depend.

“They have become ageing monocultures; disruptive innovators have left the industry and innovation is outsourced,” says the report.

The TEG has held three colloquiums and numerous discussion groups soliciting views from experienced individuals across the industry during the two years.

The latest paper names eight authors but many more contributed to the document and its recommendations.

Network transformation

Don Clarke, formerly of BT and CableLabs, is one of the authors of the latest paper. He also co-authored ETSI’s Network Functions Virtualisation (NFV) paper that kickstarted the telcos’ network transformation strategies of the last decade.

Many of the changes sought in the original NFV paper have come to pass.

Networking functions now run as software and no longer require custom platforms. To do that, the operators have embraced open interfaces that allow disaggregated designs to tackle vendor lock-in. The telcos have also adopted open-source software practices and spurred the development of white boxes to expand equipment choice.

Yet the TEG paper laments the industry’s continued reliance on large vendors while smaller telecom vendors – seen as vital to generate much-needed competition and innovation – struggle to get a look-in.

The telecom ecosystem

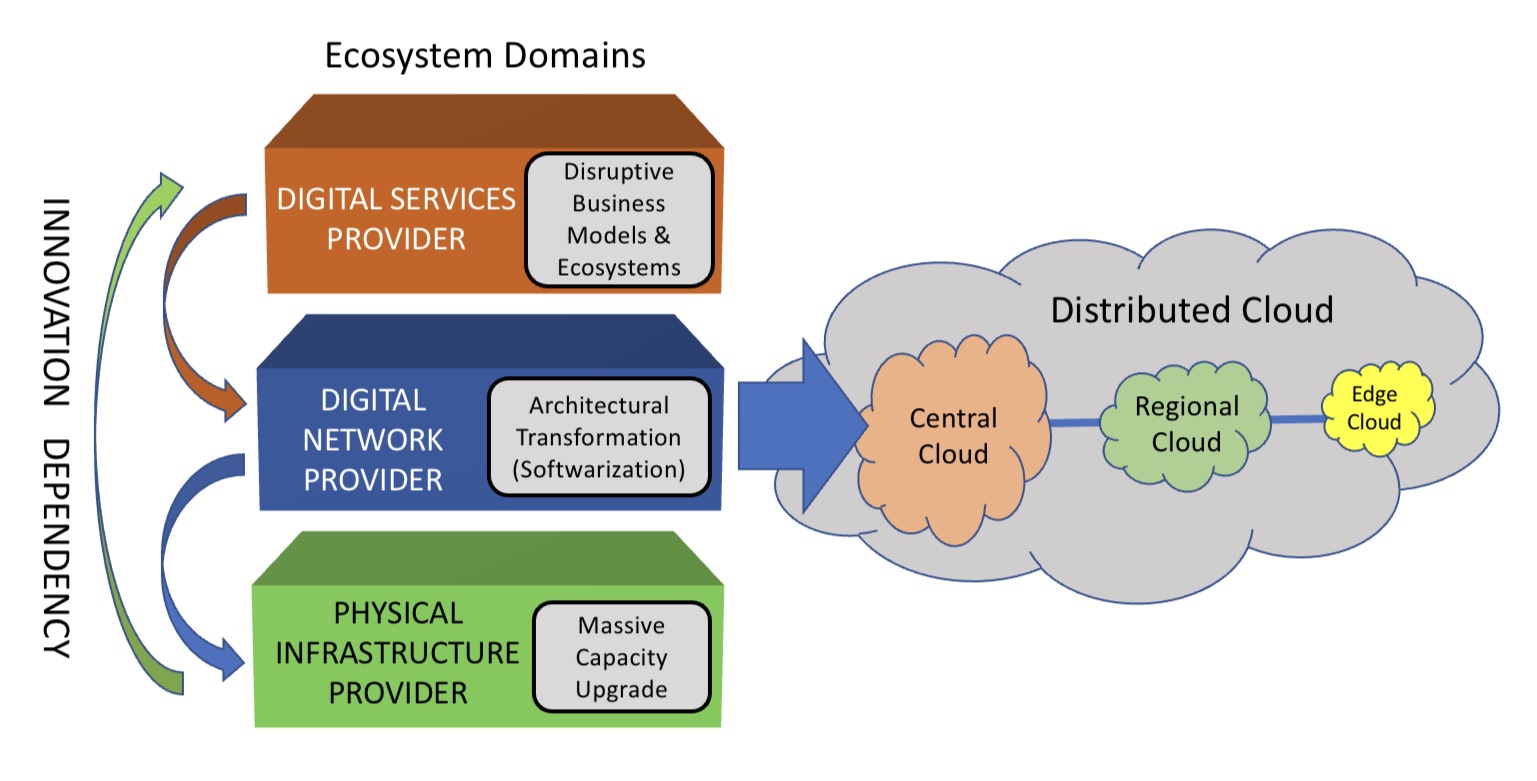

The TEG segments the telecommunications ecosystem into three domains (see diagram).

The large-scale data centre players are the digital services providers (top layer). In this domain, innovation and competition are greatest.

The digital network provider domain (middle layer) is served by a variety of players, notably the cloud providers, while it is the telcos that dominate the physical infrastructure provider domain.

At this bottom layer, competition is low and overall investment in infrastructure is inadequate. A third of the world’s population still has no access to the internet, notes the report.

The telcos should also be exploiting the synergies between the domains, says the TEG, yet struggle to do so. But more than that, the telcos can be a barrier.

Clarke cites the emerging metaverse that will support immersive virtual worlds as an example.

Metaverse

The “Metaverse” is a concept being promoted by the likes of Meta and Microsoft and has been picked up by the telcos, as evident at this week’s MWC Barcelona 22 show.

Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg recently encouraged his staff to focus on long-term thinking as the company transitions to become a metaverse player. “We should take on the challenges that will be the most impactful, even if the full results won’t be seen for years,” he said.

Telcos should be thinking about how to create a network that enables the metaverse, given the data for rendering metaverse environments will come through the telecom network, says Clarke.

“The real innovation will come when you try and understand the needs of the metaverse in terms of networking, and then you get into the telco game,” he says.

Any concentration of metaverse users will generate a data demand likely to exhaust the network capacity available.

“Telcos will say, ‘We aren’t upgrading capacity because we are not getting a return,’ and then metaverse innovation will be slowed down,” says Clarke.

He says much of the innovation needed for the metaverse will be in the network and telcos need to understand the opportunities for them. “The key is what role will the telcos have, not in dollars but network capability, then you start to see where the innovation needs to be done.”

The challenge is that the telcos can’t see beyond their immediate operational challenges, says Clarke: “Anything new creates more operational challenges and therefore needs to be rejected because they don’t have the resources to do anything meaningful.”

He stresses he is full of admiration for telcos’ operations staff: “They know their game.” But in an environment where operational challenges are avoided, innovation is less important.

TEG’s action plan

TEG’s report lists direct actions telcos can take regarding innovation. These cover funding, innovation processes, procurement and increasing competition.

Many of the proposals are designed to help smaller vendors overcome the challenges they face in telecoms. TEG views small vendors and start-ups as vital for the industry to increase competition and innovation.

Under the funding category, TEG wants telcos to allocate a least 5 per cent of procurement to start-ups and small vendors. The group also calls for investment funds to be set up that back infrastructure and middleware vendors, not just over-the-top start-ups.

For innovation, it wants greater disaggregation so as to steer away from monolithic solutions. The group also wants commitments to fast lab-to-field trials (a year) and shorter deployment cycles (two years maximum) of new technologies.

Competition will require a rethink regarding small vendors. At present, all the advantages are with the large vendors. It lists six measures how telcos can help small vendors win business, one being to stop forcing them to partner with large vendors. The TEG wants telcos to ensure enough personnel that small vendors get all the “airtime” they need with the telcos.

Lastly, concerning procurement, telcos can do much more.

One suggestion is to stop sending small vendors large, complex request for proposals (RFPs) that they must respond to in short timescales; small vendors can’t compete with the large RFP teams available to the large vendors.

Also, telcos should stop their harsh negotiating terms such as a 30 per cent additional discount. Such demands can hobble a small vendor.

Innovation

“Innovation comes from left field and if you try to direct it with a telco mindset, you miss it,” says Clarke. “Telcos think they know what ‘good’ looks like when it comes to innovation, but they don’t because they come at it from a monoculture mindset.”

He said that in the TEG discussions, the idea of incubators for start-ups was mentioned. “We have all done incubators,” he says. But success has been limited for the reasons cited above.

He also laments the lack of visionaries in the telecom industry.

A monoculture organisation rejects such individuals. “Telcos don’t like visionaries because culturally they are annoying and they make their life harder,” he says. “Disruptors have left the industry.”

Prospects

The authors are realistic.

Even if their report is taken seriously, they note any change will take time. They also do not expect the industry to be able to effect change without help. The TEG wants government and regulator involvement if the long-term prospects of a crucial industry are to be ensured.

The key is to create an environment that nurtures innovation and here telcos could work collectively to make that happen.

“No telco has it all, but individual ones have strengths,” says Clarke. “If you could somehow combine the strengths of the particular telcos and create such an environment, things will emerge.”

The trick is diversity – get people from different domains together to make judgements as to what promising innovation looks like.

“Bring together the best people and marvelous things happen when you give them a few beers and tell them to solve a problem impacting all of them,” says Clarke. “How can we make that happen?”