Ciena to sell its own coherent modules

The systems vendor is expanding its offerings to include WaveLogic modem chips and coherent optical modules.

Ciena is developing its own coherent modules to sell to the telecom and datacom markets.

The system vendor has set up the Optical Microsystems Division business unit to promote its WaveLogic coherent modem technology to the marketplace. Until now it has licensed its WaveLogic Ai digital signal processor (DSP) to module makers Lumentum, NeoPhotonics and Oclaro. But now it is planning to sell its own coherent modules.

In a job advert for a head of sales channel development, Ciena says the Optical Microsystems Division's goal is ‘to develop and productize electro-optic components and modules for sale to global systems integrator customers to be incorporated in their products for sale to telecom and data network customers’.

And at the recent European Conference on Optical Communication (ECOC) held in Rome, a network equipment manufacturer said it was approached by Ciena enquiring if it was interested in buying coherent modules from the company.

Ciena would not comment when asked if it will sell its own coherent modules. Instead, the company pointed to statements it made during its fourth quarter 2017 earnings call that outlined the creation of the Optical Microsystems Division with the stated goal of generating $50 million annual revenues by year-end 2020.

[At ECOC], a network equipment manufacturer said it was approached by Ciena enquiring if it was interested in buying coherent modules from the company

Optical Microsystems Division

Until Ciena announced in early 2017 the licensing of its 400-gigabit WaveLogic Ai to Lumentum, NeoPhotonics and Oclaro, systems vendors kept their coherent DSPs in-house. And with good reason. These are the chips that power their leading optical platforms and enable product differentiation.

Ciena’s announcement at the time showed a willingness to pursue a different business model. By licensing its DSP to optical module makers, Ciena could break into important new markets such as China even though the move would benefit its competitors using its advanced DSP for their platforms.

But the market has changed since Ciena made the announcement and now the company is deciding how best to proceed, says Mike Genovese, managing director and senior equity research analyst at MKM Partners.

“At the time of the announcement it seemed there was a big opportunity selling the [coherent] modem into Chinese OEMs,” says Genovese. “But that seems less likely now because Chinese OEMs want to assemble their own modules out of components they buy and make.”

The result is that the opportunity has shifted to data centre interconnect. “But there are decisions that need to be made,” says Genovese. “For example, does Ciena want to make its modem product a [pluggable] 400ZR solution?”

It is a view shared by Sterling Perrin, principal analyst, optical networking and transport at Heavy Reading.

“It [the licensing of its DSP] was originally built around breaking into the China market. That strategy now looks must riskier than it did originally, so I’m certain they are looking at every alternative,” says Perrin. ”The main goal is to get the most return-on-investment on the money they put into building a WaveLogic generation, and using that money to fund the next generation of DSP investment.”

At the time of the announcement it seemed there was a big opportunity selling the [coherent] modem into Chinese OEMs. But that seems less likely now.

Pluggables are going to become an important opportunity for coherent technology, says Andrew Schmitt, founder and directing analyst at Cignal AI. Schmitt says the next stage of coherent’s development - what he calls the fourth generation of coherent - will be pluggable from the start and more standards-based than any wavelength-division multiplexing (WDM) pluggable that has preceded it.

“It will address a large portion of the overall market - not just cloud operator data centreinterconnect,” says Schmitt. “Equipment vendors will need to adjust their strategies as many standalone optical hardware applications will be displaced by pluggable coherent.”

Ciena also has all the required technologies. As well as its WaveLogic modem technology, it has high-speed optical component expertise that it gained with the 2016 acquisition of Teraxion’s photonics division. The Teraxion group had indium phosphide and silicon photonics technologies.

All change

The agreement between Ciena and the three optical module makers also included an option where future WaveLogic DSPs would be made available to the three for applications such as 400-gigabit pluggables.

NeoPhotonics says that Ciena’s general strategy of bringing its WaveLogic Ai technology to a larger market and application space has not changed.

Equipment vendors will need to adjust their strategies as many standalone optical hardware applications will be displaced by pluggable coherent

Is Ciena going straight to market with future WaveLogic-based modules?

“How the modules are marketed may follow different models in the future; there is always an evolution in business models as the market shifts,” says Ferris Lipscomb, NeoPhotonics’ vice president of marketing. “Our intention is to continue to be a partner and bring value to the Ciena Microsystems business wherever possible.”

Lumentum would not comment on what the status was regarding using future coherent DSPs, nor would it say whether Ciena is to sell its own modules. Lumentum did say that it has a close relationship with Ciena and that it continues to support partnership opportunities.

But the possibility of Ciena selling modules to the marketplace is not ruled out by Ciena’s third optical module partner, Oclaro.

Yves LeMaitre, chief strategy officer at Oclaro says that Ciena’s recent announcements could point to a new strategic direction. “At this point, it is unclear how they are going to do this,” he says. Oclaro also does not know yet if it will gain access to new WaveLogic designs.

LeMaitre views the options with Ciena’s coherent technology as part of a broader debate as to how systems vendors should adapt their business models in an environment of change brought about by software-defined networks and open design frameworks.

The fact that internet content providers purchase optics directly, as do certain service providers, creates a dilemma for the systems vendors. “How are they going to go to the market to address this?” says LeMaitre. “Are they going to rely on a partnership with module makers or are they going to address the market on their own?”

Oclaro says it remains ‘very interested’ in working with Ciena if it is willing to give the module maker access to future DSP designs for pluggables.

Optical module trends: A conversation with Finisar

Finisar demonstrated recently a raft of new products that address emerging optical module developments. These include:

- A compact coherent integrated tunable transmitter and receiver assembly

- 400GBASE-FR8 and -LR8 QSFP-DD pluggable modules and a QSFP-DD active optical cable

- A QSFP28 100-gigabit serial FR interface

- 50-gigabit SFP56 SR and LR modules

Rafik Ward, Finisar’s general manager of optical interconnects, explains the technologies and their uses.

Compact coherent

Finisar is sampling a compact integrated assembly that supports 100-gigabit and 200-gigabit coherent transmission.

The integrated tunable transmitter and receiver assembly (ITTRA), to give it its full title, includes the optics and electronics needed for an analogue coherent optics interface.

The 32-gigabaud ITTRA includes a tunable laser, optical amplifier, modulators, modulator drivers, coherent mixers, a photo-detector array and the accompanying trans-impedance amplifiers, all within a gold box. “An entire analogue coherent module in a footprint that is 70 percent smaller than the size of a CFP2 module,” says Ward. The ITTRA's power consumption is below 7.5W.

Rafik WardFinisar says the ITTRA is smaller than the equivalent integrated coherent transmitter-receiver optical sub-assembly (IC-TROSA) design being developed by the Optical Internetworking Forum (OIF).

Rafik WardFinisar says the ITTRA is smaller than the equivalent integrated coherent transmitter-receiver optical sub-assembly (IC-TROSA) design being developed by the Optical Internetworking Forum (OIF).

“We potentially could take this device and enable it to work in that [IC-TROSA] footprint,” says Ward.

Using the ITTRA enables higher-density coherent line cards and frees up space within an optical module for the coherent digital signal processor (DSP) for a CFP2 Digital Coherent Optics (CFP2-DCO) design.

Ward says the CFP2 is a candidate for a 400-gigabit coherent pluggable module along with the QSFP-DD and OSFP form factors. “All have their pros and cons based on such fundamental things as the size of the form factor and power dissipation,” says Ward.

But given coherent DSPs implemented in 7nm CMOS required for 400 gigabit are not yet available, the 100 and 200-gigabit CFP2 remains the module of choice for coherent pluggable interfaces.

The demonstration of the ITTRA implementing a 200-gigabit link using 16-QAM at OFC 2018. Source: Finisar

The demonstration of the ITTRA implementing a 200-gigabit link using 16-QAM at OFC 2018. Source: Finisar

400 gigabits

Finisar also demonstrated its first 400-gigabit QSFP-DD pluggable module products based on the IEEE standards: the 2km 400GBASE-FR8 and the 10km 400GBASE-LR8. The company also unveiled a QSFP-DD active optical cable to link equipment up to 70m apart.

The two QSFP-DD pluggable modules use eight 50-gigabit PAM-4 electrical signal inputs that are modulated onto eight lasers whose outputs are multiplexed and sent over a single fibre. Finisar chose to implement the IEEE standards as its first QSFP-DD products as they are low-power and lower risk 400-gigabit solutions.

The alternative 2km 400-gigabit design, developed by the 100 Lambda MSA, is the 400G-FR4 that uses four 100-gigabit optical lanes. “This has some risk elements to it such as the [PAM-4] DSP and making 100-gigabit serial lambdas work,” says Ward. “We think the -LR8 and -FR8 are complementary and could enable a fast time-to-market for people looking at these kinds of interfaces.”

The QSFP-DD active optical cable may have a reach of 70m but typical connections are 20m. Finisar uses its VCSEL technology to implement the 400-gigabit interface. At the OFC show in March, Finisar demonstrated the cable working with a Cisco high-density port count 1 rack-unit switch.

I sometimes get asked by customers what is the best way to get to higher-density 100 gigabit. I point to the 400-gigabit DR4.

QSFP28 FR

Finisar also showed it 2km QSFP28 optical module with a single wavelength 100-gigabit PAM-4 output. The QSFP28 FR takes four 25 gigabit-per-second electrical interfaces and passes them through a gearbox chip to form a 50-gigabaud PAM-4 signal that is used to modulate the laser.

The QSFP28 FR is expected to eventually replace the CWDM4 that uses four 25-gigabit wavelengths multiplexed onto a single fibre. “The end-game is to get a 100-gigabit serial module,” says Ward. “This module represents the first generation of that.”

Finisar is also planning a 500m QSFP28 DR. The QSFP28 DR and FR will work with the 500m IEEE 400GBASE-DR4 that has four outputs, each a fibre carrying a 100-gigabit PAM-4 signal, with the -DR4 outputs interfacing with up to four FR or DR modules.

“I sometimes get asked by customers what is the best way to get to higher-density 100 gigabit,” says Ward. “I point to the 400 gigabit DR4, even though we call it a 400-gigabit part, it is also a 4x100-gigabit DR solution.”

Ward says that the 500m reach of the DR is sufficient for the vast majority of links in the data centre.

SFP56 SR and LR

Finisar has also demonstrated two SFP56 modules: a short reach (SR) version that has a reach of 100m over OM4 multi-mode fibre and the 10km LR single-mode interface. The SR is VSCEL-based while the LR uses a directly-modulated distributed feedback laser.

The SFP is deployed widely at speeds up to and including 10 gigabits while the 25-gigabit SFP shipments are starting to ramp. The SFP56 is the next-generation SFP module with a 50-gigabit electrical input and a 50-gigabit PAM-4 optical output.

The SFP56 will be used for several applications, says Finisar. These include linking servers to switches, connecting switches in enterprise applications, and 5G wireless applications.

Finisar says its 50 and 100 gigabit-per-lane products will likely be released throughout 2019, in line with the industry. “The 8-channel devices will likely come out at least a few quarters before the 4-channel devices,” says Ward.

COBO issues industry’s first on-board optics specification

- COBO modules supports 400-gigabit and 800-gigabit data rates

- Two electrical interfaces have been specified: 8 and 16 lanes of 50-gigabit PAM-4 signals.

- There are three module classes to support designs ranging from client-slide multi-mode to line-side coherent optics.

- COBO on-board optics will be able to support 800 gigabits and 1.6 terabits once 100-gigabit PAM-4 electrical signals are specified.

Source: COBO

Source: COBO

Interoperable on-board optics has moved a step closer with the publication of the industry’s first specification by the Consortium for On-Board Optics (COBO).

COBO has specified modules capable of 400-gigabits and 800-gigabits rates. The designs will also support 800-gigabit and 1.6-terabit rates with the advent of 100-gigabit single-lane electrical signals.

“Four hundred gigabits can be solved using pluggable optics,” says Brad Booth, chair of COBO and principal network architect for Microsoft’s Azure Infrastructure. “But if I have to solve 1.6 terabits in a module, there is nothing out there but COBO, and we are ready.”

Origins

COBO was established three years ago to create a common specification for optics that reside on the motherboard. On-board optics is not a new technology but until now designs have been proprietary.

I have to solve 1.6 terabits in a module, there is nothing out there but COBO, and we are ready

Brad BoothSuch optics are needed to help address platform design challenges caused by continual traffic growth.

Brad BoothSuch optics are needed to help address platform design challenges caused by continual traffic growth.

Getting data on and off switch chips that are doubling in capacity every two to three years is one such challenge. The input-output (I/O) circuitry of such chips consumes significant power and takes up valuable chip area.

There are also systems challenges such as routing the high-speed signals from the chip to the pluggable optics on the platform’s faceplate. The pluggable modules also occupy much of the faceplate area and that impedes the air flow needed to cool the platform.

Using optics on the motherboard next to the chip instead of pluggables reduces the power consumed by shortening the electrical traces linking the two. Fibre rather than electrical signals then carries the data to the faceplate, benefiting signal integrity and freeing faceplate area for the cooling.

Specification 1.0

COBO has specified two high-speed electrical interfaces. One is 8-lanes wide, each lane being a 50-gigabit 4-level pulse-amplitude modulation (PAM-4) signal. The interface is based on the IEEE’s 400GAUI-8, the eight-lane electrical specification developed for 400 Gigabit Ethernet.

The second electrical interface is a 16-lane version for an 800-gigabit module. Using a 16-lane design reduces packaging costs by creating an 800-gigabit module instead using two separate 400-gigabit ones. Heat management is also simpler with one module.

There are also systems benefits using an 800-gigabit module.“As we go to higher and higher switch silicon bandwidths, I don’t have to populate as many modules on the motherboard,” says Booth.

The latest switch chips announced by several companies have 12.8 terabits of capacity that will require 32, 400-gigabit on-board modules but only 16, 800-gigabit ones. Fewer modules simplify the board’s wiring and the fibre cabling to the faceplate.

Designers have a choice of optical formats using the wider-lane module, such as 8x100 gigabits, 2x400 gigabits, and even 800 gigabits.

COBO has tested its design and shown it can support a 100-gigabit electrical interface. The design uses the same connector as the OSFP pluggable module.

“In essence, with an 8-lane width, we could support an 800-gigabit module if that is what the IEEE decides to do next,” says Booth. “We could also support 1.6 terabits if that is the next speed hop.”

It is very hard to move people from their standard operating model to something else until there is an extreme pain point

Form factor and module classes

The approach chosen by COBO differs from proprietary on-board optics designs in that the optics is not mounted directly onto the board. Instead, the COBO module resembles a pluggable in that once placed onto the board, it slides horizontally to connect to the electrical interface (see diagram, top).

A second connector in the middle of the COBO module houses the power, ground and control signals. Separating these signals from the high-speed interface reduces the noise on the data signals. In turn, the two connectors act as pillars supporting the module.

The robust design allows the modules to be mounted at the factory such that the platform is ready for operation once delivered at a site, says Booth.

COBO has defined three module classes that differ in length. The shortest Class A modules are used for 400-gigabit multi-mode interfaces while Class B suits higher-power IEEE interfaces such as 400GBASE-DR4 and the 100G Lambda MSA’s 400G-FR4.

The largest Class C module is for the most demanding and power-hungry designs such as the coherent 400ZR standard. “Class C will be able to handle all the necessary components - the optics and the DSP - associated with that [coherent design],” says Booth.

The advantage of the on-board optics is that it is not confined to a cage as pluggables are. “With an on-board optical module, you can control the heat dissipation by the height of the heat sink,” says Booth. “The modules sit flatter to the board and we can put larger heat sinks onto these devices.”

We realised we needed something as a stepping stone [between pluggables and co-packaged optics] and that is where COBO sits

Next steps

COBO will develop compliance-testing boards so that companies developing COBO modules can verify their designs. Booth hopes that by the ECOC 2018 show to be held in September, companies will be able to demonstrate COBO-based switches and even modules.

COBO will also embrace 100-gigabit electrical work being undertaken by the OIF and the IEEE to determine what needs to be done to support 8-lane and 16-lane designs. For example, whether the forward-error correction needs to be modified or whether existing codes are sufficient.

Booth admits that the industry remains rooted to using pluggables, while the move to co-packaged optics, where the optics and the chip are combined in the same module - remains a significant hurdle, both in terms of packaging technology and the need for vendors to change their business models to build such designs.

“It is very hard to move people from their standard operating model to something else until there is an extreme pain point,” says Booth.

Setting up COBO followed the realisation that a point would be reached when faceplate pluggables would no longer meet demands while in-packaged technology would not be ready.

“We realised we needed something as a stepping stone and that is where COBO sits,” says Booth.

Further information

For information on the COBO specification, click here.

DustPhotonics reveals its optical transceiver play

A start-up that has been active for a year has dropped its state of secrecy to reveal it is already shipping its first optical transceiver product.

The company, DustPhotonics, is backed by private investors and recently received an undisclosed round of funding that will secure the company’s future for the next two years.

Product plans

DustPhotonics' first product is the multi-mode 100m-reach 100GBASE-SR4 QSFP28. The company will launch its first 400-gigabit optical modules later this year.

Ben Rubovitch

Ben Rubovitch

“We probably are going to be one of the first to market with [400-gigabit] QSFP-DD and OSFP multi-mode solutions,” says Ben Rubovitch, CEO of DustPhotonics.

The start-up has developed 50 gigabit-per-lane technology required for higher-speed modules such as the QSFP56, QSFP-DD and OSPF pluggables. The QSFP-DD form factor is designed to be backwards compatible with the QSFP and QSFP28 and is backed by the likes of Facebook and Cisco, while the OSFP is a new form factor supported by Google and switch maker Arista Networks.

DustPhotonics chose the 4-lane 25-gigabit QSFP28 to prove the working of its 50 gigabit-per-lane technology. “The reason we did that is that the PAM-4 chipsets weren’t ready when we started,” says Rubovitch. “So we invested the first year solving the production issues and the optical interface and used the QSFP28 as the platform.”

The challenge with a 50 gigabit-per-lane optical interface is that the photo-detector aperture used is smaller. “So on our QSFP28 we used a small photo-detector to prove the optical solution,” says Rubovitch.

The start-up is now developing faster speed multi-mode designs: a 200-gigabit QSFP56 pluggable, a 400-gigabit QSFP-DD implementing the 400GBASE-SR8 standard and a similar active optical cable variant; products that it hopes to sample in the second quarter of this year. This will be followed by similar SR8 implementations using the OSFP.

DustPhotonics' optical product roadmap. Source: Gazettabyte/ DustPhotonics.

DustPhotonics' optical product roadmap. Source: Gazettabyte/ DustPhotonics.

DustPhotonics is also adapting its optical packaging technology to support single-mode designs: the 500m IEEE 400GBASE-DR4 and the 2km 400G-FR4, part of the 100G Lambda multi-source agreement (MSA). Both the DR4 and FR4 designs use 100-gigabit optical lanes.

Technology

Rubovitch says that despite the many optical transceiver players and the large volumes of modules now manufactured, pluggable optics remain expensive. “The front panel of a top-of-rack switch [populated with modules] costs ten times more than the switch itself,” he says.

DustPhotonics has tackled the issue of cost by simplifying the module’s bill of materials and the overall manufacturing process.

The start-up buys the lasers and electronic ICs needed and adds its own free-space optics for both multi-mode and single-mode transceiver designs. “It is all plastic-molded so we don’t use any glass types or any integrated lasers and that simplifies much of the process,” says Rubovitch. Indeed, he claims the design reduces the bill of materials of its transceivers by between 30 and 50 percent.

The front panel of a top-of-rack switch [populated with modules] costs ten times more than the switch itself

DustPhotonics has also developed a passive alignment process. “We have narrowed the one accurate step - where we align the optics - to one machine,” says Rubovitch. “This compares to two steps ‘accurate’ and one step ‘align’ for active alignment.” Active alignment for a QSFP28 module takes ten minutes, he says, whereas DustPhotonics’ passive alignment process takes under a minute per module.

“There is also a previous manufacturing stage where we place the VCSELs and photo-detectors on a substrate itself and we don’t need accuracy here, unlike other solutions,” he says.

The overall result is a simpler, more cost-effective design. “We are already manufacturing in a volume production line and we see the numbers and how competitive we are, and it is going to create an even larger advantage at 400 gigabits,” says Rubovitch.

DustPhotonics’ passive alignment process takes under a minute per module

What next?

DustPhotonics is also developing embedded optics, where the optics are placed next to an ASIC, and even in-package designs where the optics and ICs are co-packaged.

Rubovitch says such technologies will be needed because of the very high power 100-gigabit electrical transceivers consume on a switch chip, for example, as well the silicon area they require; precious silicon real estate needed to cope with the ever-increasing packet-processing demands. “Bringing the optics very close [to the chip] can help solve those issues for the switch providers,” he says.

As Rockley Photonics’ CEO, Andrew Rickman, observed recently, combining optics with the switch silicon has long been discussed yet has still to be embraced by the switch chip makers. This explains why Rockley developed its own switch ASIC to demonstrate a complete in-packaged reference design.

Rubovitch agrees that the concept of optics replacing electrical interfaces has long been spoken of but that hasn’t happened due to copper speeds continuing to advance. There is already a 100 gigabit-per-lane solution that will meet the demands of the next generation of switch designs, he says: “It really depends on what is going to be the next leap: 200 gigabits or 400-gigabits.”

Using optics to replace electrical interfaces could come with the advent of 25 terabit switch silicon or maybe the generation after. “Or maybe something in between: 25 terabit solutions will start to move gradually to a more packaged solution or at least closer on-board optics,” concludes Rubovitch.

Finisar's 10 Gig bi-directional DWDM architecture

Finisar has developed a bi-directional 10-gigabit SFP+ module for the metro-access market. The dense wavelength-division multiplexing (DWDM) module is designed to expand capacity at locations where fibre is scarce. And being tunable, the SFP+ also simplifies network planning for the operators.

Finisar demonstrated the module working at the recent ECOC 2017 show held in Gothenburg.

Market applications

Interest is growing in using WDM optics for wireless, metro-access and cable networks that are undergoing upgrades. The interest in WDM at the network edge is due to a need to use fibre resources more efficiently. “We are seeing that globally, more and more dark fibre is being used up,” says Leo Lin, director of product line management at Finisar.

Leo LinGiven the cost of leasing and installing fibre, operators are keen to make the best use of their existing fibre and are willing to pay more for WDM optics.

Leo LinGiven the cost of leasing and installing fibre, operators are keen to make the best use of their existing fibre and are willing to pay more for WDM optics.

According to Finisar, leasing a fibre can cost $250-$2,000 per fibre annually while the cost of installing fibre can be $500,000 per 10km. “Using WDM optics, you can get payback in less than a year,” says Lin.

LightCounting Market Research's latest forecast estimates that the global wireless transceiver market for 10 gigabit WDM will be approximately $400 million in 2022.

Finisar’s bi-directional 10-gigabit SFP+ product is also being aimed at two emerging ITU Telecom standards: G.metro and NG-PON2.

G.Metro and NG-PON2

The G.metro standard supports up to 40 DWDM wavelengths on a 100GHz wavelength grid. Tuneable transponders each at 10 gigabits-per-second (Gbps) are used and have a reach of up to 20km without amplification.

NG-PON2 is a time and wavelength division multiplexing, passive optical network (TWDM-PON) standard. “In addition to TWDM-PON, they want to have a few dedicated point-to-point WDM links, an overlay on top of the PON,” says Lin.

G.metro uses both the C-band and the L-band: one band is used for the sent wavelengths and the other band for the received wavelengths. In contrast, Finisar’s bi-directional approach sends and receives wavelengths using the C-band only.

“The G.metro standard calls out bi-directional and tuneable optics, and our bi-directional module product can be directly used here,” says Lin. “Since ECOC, we have had quite some support from operators and OEMs that will add our architecture as one of the channel options in both G.metro and NG-PON2.”

Bidi design

Finisar describes its design as a dual-band bi-directional DWDM approach. To understand the design, it helps to compare it to existing DWDM duplex and single fibre schemes.

Standard DWDM (A), a hybrid bi-directional scheme that uses 50GHz AWGs (B), and the bi-directional approach (C) using the C- and L-bands being proposed for G.metro and NG-PON2. Finisar's approach is shown in the diagram below. Source Finisar.

Standard DWDM (A), a hybrid bi-directional scheme that uses 50GHz AWGs (B), and the bi-directional approach (C) using the C- and L-bands being proposed for G.metro and NG-PON2. Finisar's approach is shown in the diagram below. Source Finisar.

With standard DWDM, two fibres are used, each having a multiplexer and demultiplexer pair. The C-band is used with wavelengths sent down one fibre and received on the other (see diagram A).

The hybrid bi-directional DWDM design (diagram B) sends wavelengths in both directions on one fibre. The hybrid approach is growing in popularity, says Finisar, to address fibre scarcity, for example between a central office and a remote node. For the hybrid scheme, only a single multiplexer-demultiplexer pair is needed. But to fit all the wavelengths on one fibre, a 50GHz channel mux-demux is used rather than a cheaper 100GHz one.

Another bi-directional scheme - one that G.metro and NG-PON2 are promoting - uses 100GHz channels but requires both the C-band and the L-band (diagram C). Here, east-to-west traffic is sent across one band while west-to-east traffic is sent on the other.

“This approach requires cyclic arrayed-waveguide gratings,” says Lin. A cyclic or colourless arrayed-waveguide grating (AWG) can separate or combine wavelengths across multiple bands. But unlike the hybrid bi-directional case, one fibre only connects to each bi-directional transceiver hosting a C-band wavelength in one direction and an L-band one travelling in the opposite direction. Using fewer fibres saves cost and space.

Finisar’s bi-directional design is similar but with one important twist: only the C-band is used.

To do this, two carriers are placed into the single 100GHz channel: one an upstream wavelength and one a downstream one. The result is 40, 10Gbps wavelengths - 80 carriers in total - spread across the C-band (see diagram below).

Finisar's bi-directional architecture uses two carriers per channel spread across the C-band. Source: Finisar

Finisar's bi-directional architecture uses two carriers per channel spread across the C-band. Source: Finisar

A tuneable filter is used in the module not only to match the channel that the remote module’s tuneable laser will use, but also to select the particular band in a given channel, either the upstream or downstream band. The result is that one bi-directional module can be used for all 40 channels. “One single part number for the far end and the near end,” says Lin.

The technical challenge Finisar faced to make its design work is separating the two closely spaced carriers in a 100GHz channel.

Finisar says that with a 50GHz DWDM system, the wavelength must sit centrally in the channel and that requires a wavelength locker. The two carriers within its 100GHz band are not placed centrally yet Finisar has developed a way to separate the two without needing wavelength-locker technology.

The tuneable bi-directional approach also simplifies network planning. If an operator wants to add a new wavelength and drop it at an existing node, the node’s optical add-drop multiplexer does not need to be upgraded.

“All operators have different channel plans and customised optical add-drop multiplexers in the field,” says Lin. “In our case, we are even simpler than the duplex. In duplex you need a multiplexer-demultiplexer pair; in our case, any AWG or thin-film filter based design can be used.”

Finisar uses an out-of-band communication channel for the central office module to co-ordinate the channel to be used with a newly inserted remote module. “You can plug in a module on any available port and it establishes a link by itself in under 10 seconds,” says Lin.

Roadmap

Finisar is working to extend the reach of its 10-gigabit bi-directional tuneable SFP+ DWDM architecture to beyond the current 40km to 60km with the use of a bi-directional EDFA.

The current 40km reach is determined by the link budget chosen for the expected use cases with the assumption being that multiple add-drop sites will exist between the central office and the remote end. “The tuneable laser used is the same that is used in our tuneable XFP+, so supporting beyond 80km is not a problem,” says Lin.

Finisar says it is working on a 25-gigabit bi-directional module that will be available in 2019.

Meanwhile, select customers are evaluating samples of the 10-gigabit bi-directional SFP+ module. General availability is expected by mid-2018.

The many paths to 400 gigabits

The race is on to deliver 400-gigabit optical interfaces in time for the next-generation of data centre switches expected in late 2018.

The industry largely agrees that a four-wavelength 400-gigabit optical interface is most desirable yet alternative designs are also being developed.

Optical module makers must consider such factors as technical risk, time-to-market and cost when choosing which design to back.

Rafik Ward, FinisarUntil now, the industry has sought a consensus on interfaces, making use of such standards bodies as the IEEE to serve the telecom operators.

Rafik Ward, FinisarUntil now, the industry has sought a consensus on interfaces, making use of such standards bodies as the IEEE to serve the telecom operators.

Now, the volumes of modules used by the internet giants are such that they dictate their own solutions. And the business case for module makers is sufficiently attractive that they are willing to comply.

Another challenge at 400 gigabits is that there is no consensus regarding what pluggable form factor to use.

“There is probably more technical risk in 400 gigabits than any of the historical data-rate jumps we have seen,” says Rafik Ward, vice president of marketing at Finisar.

Shrinking timeframes

One-hundred-gigabit interfaces are now firmly established in the marketplace. It took several generations to achieve the desired module design. First, the CFP module was used, followed by the CFP2. The industry then faced a choice between the CFP4 and the QSFP28 form factors. The QSFP28 ended up winning because the 100-gigabit module met the price, density and performance expectations of the big users - the large-scale data centre players, says Paul Brooks, director of strategy for lab and production at Viavi Solutions.

“The QSFP28 is driving huge volumes, orders of magnitude more than we see with the other form factors,” he says.

There is probably more technical risk in 400 gigabits than any of the historical data-rate jumps we have seen

It was the telcos that initially drove 100-gigabit interfaces, as with all the previous interface speeds. Telcos have rigorous optical and physical media device requirements such that the first 100-gigabit design was the 10km 100GBASE-LR4 interface, used to connect IP routers and dense wavelength-division multiplexing (DWDM) equipment.

Paul Brooks, Viavi Solutions

Paul Brooks, Viavi Solutions

But 100 gigabits is also the first main interface speed influenced by the internet giants. “One-hundred-gigabit volumes didn’t take that inflection point until we saw the PSM4 and CWDM4 [transceiver designs],” says Brooks. The PSM4 and CWDM4 are not IEEE specification but multi-source agreements (MSAs) driven by the industry.

The large-scale data centre players are now at the forefront driving 400 gigabits. They don’t want to wait for three generations of modules before they get their hands on an optimised design. They want the end design from the start.

“There was a lot of value in having iterations at 100 gigabits before we got to the high-volume form factor,” says Ward. “It will be more challenging with the compressed timeframe for 400 gigabits.”

Datacom traffic is driven by machine-to-machine communication whereas telecom is driven by consumer demand. Machine-to-machine has twice the growth rate.

Data centre needs

Brandon Collins, CTO of Lumentum, explains that the urgency of the large-scale data centre players for 400 gigabits is due to their more pressing capacity requirements compared to the telcos.

Brandon Collings, LumentumDatacom traffic is driven by machine-to-machine communication whereas telecom is driven by consumer demand. “Machine-to-machine has twice the growth rate,” says Collins. “The expectation in the market - and everything in the market aligns with this - is that the datacom guys will be adopting in volume much sooner than the telecom guys.”

The data centre players require 400-gigabit interfaces for the next-generation 6.4- and 12.8-terabit top-of-rack switches in the data centre.

“The reason why the top-of-rack switch is going to need 400-gigabit uplinks is because server speeds are going to go from 25 gigabits to 50 gigabits,” says Adam Carter, chief commercial operator for Oclaro.

A top-of-rack switch’s downlinks connect to the servers while the uplinks interface to larger ‘spine’ switches. For a 36-port switch, if four to six ports are reserved for uplinks and the remaining ports are at 50 gigabits-per-second (Gbps), 100-gigabit uplinks cannot accommodate all the traffic.

The 6.4-terabit and 12.8-terabit switches are expected towards the end of next year. These switches will be based on silicon such as Broadcom’s Tomahawk-III, start-up Innovium’s Teralynx and Mellanox’s Spectrum-2. All three silicon design examples use 50-gigabit electrical signalling implemented using 4-level pulse-amplitude modulation (PAM-4).

PAM-4, a higher order modulation scheme, used for the electrical and optical client interfaces is another challenge at 400-gigabit. The use of PAM-4 requires a slight increase in bandwidth, says Brooks, and introduces a loss that requires compensation using forward error correction (FEC). “Four-hundred-gigabits is the first Ethernet technology where you always have FEC on,” he says.

CFP8

The modules being proposed for 400-gigabit interfaces include the CFP8, the Octal Small Form Factor (OSFP) and the double-density QSFP (QSFP-DD) pluggable modules. COBO, the interoperable on-board optics standard, will also support 400-gigabit interfaces.

The QSFP-DD is designed to be backward compatible with the QSFP and QSFP28 pluggables while the OSFP is a new form factor.

At OFC earlier this year, several companies showcased 400-gigabit CFP8-based designs.

NeoPhotonics detailed a CFP8 implementing 400GBASE-LR8, the IEEE 802.3bs Task Force’s 10km specification that uses eight wavelengths, each at 50-gigabit PAM4. Finisar announced two CFP8 transceivers: the 2km 400GBASE-FR8 and the 10km 400GBASE-LR8. Oclaro also announced two CFP8 designs: the 10km 400GBASE-LR8 and an even longer reach 40km version.

The 400-gigabit CFP8 is aimed at traditional telecom applications such as linking routers and transport equipment.

NeoPhotonics’ CFP8 is not yet in production and the company says it is not seeing a present need. “There is probably a short window before it gets replaced by the QSFP-DD or, on the telecom side, the OSFP,” says Ferris Lipscomb, vice president of marketing at NeoPhotonics.

Finisar expects its 400-gigabit CFP8 products by the year-end, while Oclaro is sampling its 10km 400-gigabit CFP8.

But the large-scale data centre players are not interested in the CFP8 which they see as too bulky for the data centre. Instead, Amazon, Facebook, and equipment vendor Cisco Systems are backing the higher-density QSFP-DD, while Google and Arista Networks are proponents of the OSFP.

“The data centre players don’t need IEEE standardisation, they need the lowest cost and the most compact form factor,” says Lumentum’s Collings.

QSFP-DD and OSFP

To achieve 400 gigabits, the QSFP-DD has twice the number of electrical lanes of the QSFP, going from four to eight, while each lane’s speed is doubled to 56Gbps using PAM-4.

“Time and time again we have heard with the QSFP-DD that plugging in legacy modules is a key benefit of that technology,” says Scott Sommers, group product manager at Molex and a co-chair of the QSFP-DD MSA. The power envelope of the QSFP-DD is some 12W.

Yasunori Nagakubo, Fujitsu Optical ComponentsYasunori Nagakubo, director of marketing at Fujitsu Optical Components also highlights the high-density merits of the QSFP-DD. Up to 36 ports can fit on the front panel of a one-rack-unit (1RU) box, enabling a throughput of 14.4 terabits.

In contrast, the OSFP has been designed with a fresh sheet of paper. The form factor has a larger volume and surface area compared to the QSFP-DD and, accordingly, has a power envelope of some 16W. Up to 32 OSFP ports can fit on a 1RU front panel.

“The QSFP-DD is a natural evolution of the QSFP and is used for switch-to-switch interconnect inside the data centre,” says Robert Blum, director of strategic marketing and business development at Intel’s silicon photonics product division. He views the OSFP as being a more ambitious design. “Obviously, you have a lot of overlap in terms of applications,” says Blum. “But the OSFP is trying to address a wider segment such as coherent and also be future proofed for 800 gigabits.”

“A lot of people are trying to make everything fit inside a QSFP-DD but, after all, the OSFP is still a bigger form factor which is easier for different components to fit in,” says Winston Way, CTO, systems at NeoPhotonics. Should a 400-gigabit design meet the more constrained volume and power requirements of the QSFP-DD, the design will also work in an OSFP.

The consensus among the module makers is that neither the QSFP-DD nor the OSFP can be ignored and they plan to back both.

This [400 gigabits] may be the last hurrah for face-plate pluggables

“We have been in this discussion with both camps for quite some time and are supporting both,” says Collings. What will determine their relative success will be time-to-market issues and which switch vendors produces the switch with the selected form factors and how their switches sell. “Presumably, switches are bought on other things than which pluggable they elected to use,” says Collings.

Is having two form factors an issue for Microsoft?

“Yes and no,” says Brad Booth, principal network architect for Microsoft’s Azure Infrastructure and chair of the COBO initiative. “I understand why the QSFP-DD exists and why the OSFP exists, and both are the same reason why we started COBO.”

COBO will support 400-gigabit interfaces and also 800 gigabits by combining two modules side-by-side.

Booth believes that 400-gigabit pluggable module designs face significant power consumption challenges: “I’ve been privy to data that says this is not as easy as many people believe.”

Brad Booth, MicrosoftIf it were only 400-gigabit speeds, it is a question of choosing one of the two pluggable modules and running with it, he says. But for future Ethernet speeds, whether it is 800 gigabits or 1.6 terabits, the design must be able to meet the thermal environment and electrical requirements.

Brad Booth, MicrosoftIf it were only 400-gigabit speeds, it is a question of choosing one of the two pluggable modules and running with it, he says. But for future Ethernet speeds, whether it is 800 gigabits or 1.6 terabits, the design must be able to meet the thermal environment and electrical requirements.

“I do not get that feeling when I look at anything that is a face-plate pluggable,” says Booth. “This [400 gigabits] may be the last hurrah for face-plate pluggables.”

Formats

There are several 400-gigabit interface specifications at different stages of development.

The IEEE’s 802.3bs 400 Gigabit Ethernet Task Force has defined four 400 Gigabit specifications: a multi-mode fibre design and three single-mode interfaces.

The 100m 400GBASE-SR16 uses 16 multi-mode fibres, each at 25Gbps. The -SR16 has a high fibre count but future 400-gigabit multi-mode designs are likely to be optimised. One approach is an eight-fibre design, each at 50Gbps. And a four-fibre design could be developed with each fibre using coarse wavelength-division multiplexing (CWDM) carrying four 25-gigabit wavelengths.

The expectation is that at OFC 2018 next March, many companies will be demonstrating their 400-gigabit module designs including four-wavelength ones

The three single-mode IEEE specifications are the 500m 400GBASE-DR4 which uses four single-mode fibres, each conveying a 100-gigabit wavelength, and the 2km 400GBASE-FR8 and 10km 400GBASE-LR8 that multiplex eight wavelengths onto a single-mode fibre, each wavelength carrying a 50-gigabit PAM-4 signal.

The 2km and 10km IEEE specifications use a LAN-WDM spacing scheme and that requires tight wavelength control and hence laser cooling. The standards also use the IEEE CDAUI-8 electrical interface that supports eight 50-gigabit PAM-4 signals. The -FR8 and -LR8 standards are the first 400-gigabit specifications being implemented using the CFP8 module.

A new initiative, the CWDM8 MSA, has been announced to implement an alternative eight-wavelength design based on CWDM such that laser cooling is not required. And while CWDM8 will also use the CDAUI-8 electrical interface, the signals sent across the fibre are 50-gigabit non-return-to-zero (NRZ). A retimer chip is required to convert the input 50-gigabit PAM-4 electrical signals into 50-gigabit NRZ before being sent optically.

Robert Blum, IntelProponents of the CWDM8 MSA see it as a pragmatic solution that offers a low-risk, timely way to deliver 400-gigabit interfaces.

Robert Blum, IntelProponents of the CWDM8 MSA see it as a pragmatic solution that offers a low-risk, timely way to deliver 400-gigabit interfaces.

“When we looked at what is available and how to do an optical interface, there was no good solution that would allow us to meet those timelines, fit the power budget of the QSFP-DD and be at the cost points required for data centre deployment,” says Intel’s Blum. Intel is one of 11 founding companies backing the new MSA.

A disadvantage of the MSA is that it requires eight lasers instead of four, adding to the module’s overall cost.

“Making lasers at eight different wavelengths is not a trivial thing,” says Vivek Rajgarhia, senior vice president and general manager, lightwave at Macom.

This is what the 100G Lambda MSA aims to address with its four 100-gigabit wavelength design over duplex fibre. This can be seen as a four-wavelength CWDM complement to the IEEE’s 400GBASE-DR4 500m specification.

Vivek Rajgarhia, Macom

The first 400-gigabit standard the MSA is developing is the 400G-FR4, a 2km link that uses a CDAUI-8 interface and an internal PAM4 chip to create the 100-gigabit PAM-4 signals that are optically multiplexed onto a fibre.

The large-scale data centre players are the main drivers of four-wavelength 400-gigabit designs. Indeed, two large-scale data centre operators, Microsoft and Alibaba, have joined the 100G Lambda MSA.

“People think that because I work at Microsoft, I don’t talk to people at Google and Facebook,” says Booth. “We may not agree but we do talk.

“My point to them was that we need a CWDM4 version of 400 gigabits; the LAN-WDM eight-wavelength is a non-starter for all of us,” says Booth. “If you talk to any of the big end users, they will tell you it is a non-starter. They are waiting for the FR4.”

“Everyone wants 400 gigabit - 4x100-gigabit, that is what they are looking for,” says Rajgarhia.

If companies adopt other solutions it is purely a time-to-market consideration. “If they are going for intermediate solutions, as soon as there is 400 gigabits based on 100-gigabit serial, there is no need for them, whether it is 200-gigabit or 8x50-gigabit modules,” says Rajgarhia.

At the recent ECOC 2017 show, Macom demonstrated a 100-gigabit single-wavelength solution based on its silicon photonics optics and its 100-gigabit PAM-4 DSP chip. MultiPhy also announced a 100-gigabit PAM-4 chip at the show and companies are already testing its silicon.

The expectation is that at OFC 2018 next March, many companies will be demonstrating their 400-gigabit module designs including four-wavelength ones.

Fujitsu Optical Components says it will have a working four-wavelength 400-gigabit module demonstration at the show. “Fujitsu Optical Components favours a 4x100-gigabit solution for 400 gigabits instead of the alternative eight-wavelength solutions,” says Nagakubo. “We believe that eight-wavelength solutions will be short lived until the 4x100-gigabit design becomes available.”

The roadmap is slipping and slipping because the QSFP-DD is hard, very hard

Challenges and risk

“Everyone understands that, ultimately, the end game is the QSFP-DD but how do we get there?” says Viavi’s Brooks.

He describes as significant the challenges involved in developing a four-wavelength 400-gigabit design. These include signal integrity issues, the optics for 100-gigabit single wavelengths, the PAM-4 DSP, the connectors and the ‘insanely hot and hard’ thermal issues.

“All these problems need to be solved before you can get the QSFP-DD to a wider market,” says Brooks. “The roadmap is slipping and slipping because the QSFP-DD is hard, very hard.”

Lumentum’s Collins says quite a bit of investment has been made to reduce the cost of existing 100-gigabit CWDM4 designs and this investment will continue. “That same technology is basically all you need for 400 gigabits if you can increase the bandwidth to get 50 gigabaud and you are using a technology that is fairly linear so you can switch from NRZ to PAM-4 modulation.”

In other words, extending to a 400-gigabit four-wavelength design becomes an engineering matter if the technology platform that is used can scale.

Microsoft’s Booth is also optimistic. He does not see any challenges that suggest that the industry will fail to deliver the 400-gigabit modules that the large-scale data centre players require: “I feel very confident that the ecosystem will be built out for what we need.”

Module companies backing the most technically-challenging four-wavelength designs face the largest risk, yet also the greatest reward if they deliver by the end of 2018 and into 2019. Any slippage and the players backing alternative designs will benefit.

How the 400-gigabit market transpires will be ‘very interesting’, says Finisar’s Ward: “It will be clear who executes and who does not.”

Acacia announces a 1.2 terabit coherent module

Channel capacity and link margin can be maximised by using the fractional QAM scheme. Source: Acacia.

Channel capacity and link margin can be maximised by using the fractional QAM scheme. Source: Acacia.

The company is facing increasing market competition. Ciena has teamed up with Lumentum, NeoPhotonics, and Oclaro, sharing its high-end coherent DSP expertise with the three optical module makers. Meanwhile, Inphi has started sampling its 16nm CMOS M200, a 100- and 200-gigabit coherent DSP suitable for CFP2-ACO, CFP-DCO, and CFP2-DCO module designs.

The AC1200 is Acacia’s response, extending its high-end module offering beyond a terabit to compete with the in-house system vendors and preserve its performance lead against the optical module makers.

Enhanced coherent techniques

The AC1200 has an architecture similar to the company’s AC400 5x7-inch 400-gigabit module announced in 2015. Like the earlier module, the AC1200 features a dual-core coherent DSP and two silicon photonics transceiver chips. But the AC1200 uses a much more sophisticated DSP - the 16nm CMOS Pico device announced earlier this year - capable of supporting such techniques as variable baud rate, advanced modulation and coding schemes so that the bits per symbol can be fine-tuned, and enhanced soft-decision forward error correction (SD-FEC). The AC400 uses the 1.3 billion transistor Denali dual-core DSP while the Pico DSP has more than 2.5 billion transistors.

The result is a two-wavelength module design, each wavelength supporting from 100-600 gigabits in 50-gigabit increments.

Acacia is able to triple the module’s capacity to 1.2 terabits by incorporating a variable baud rate up to at least 69 gigabaud (Gbaud). This doubles the capacity per wavelength compared to the AC400 module. The company also uses more modulation formats including 64-ary quadrature amplitude modulation (64-QAM), boosting capacity a further 1.5x compared to the AC400’s 16-QAM.

Acacia has not detailed the module’s dimensions but says it is a custom design some 40 percent smaller in area than a 5x7-inch module. Nor will it disclose the connector type and electrical interface used to enable the 1.2-terabit throughput. However, the AC1200 will likely support 50 gigabit-per-second (Gbps) 4-level pulse-amplitude modulation (PAM-4) electrical signals as it will interface to 400-gigabit client-side modules such as the QSFP-DD.

The AC1200’s tunable baud rate range is around 35Gbaud to 69Gbaud. “The clock design and the optics could truly be continuous and it [the baud rate] pairs with a matrix of modulation formats to define a certain resolution,” says Tom Williams, senior director of marketing at Acacia Communications. Whereas several of the system vendors’ current in-house coherent DSPs use two baud rates such as 33 and 45Gbaud, or 35 and 56Gbaud, Acacia says it uses many more rates than just two or three.

The result is that at the extremes, the module can deliver from 100 gigabits (a single wavelength at some 34Gbaud and quadrature phase-shift keying - QPSK) to 1.2 terabits (using two wavelengths, each 64-QAM at around 69Gbaud).

The module also employs what Acacia refers to as very fine resolution QAM constellations. The scheme enables the number of bits per symbol to be set to any value and not be limited to integer bits. Acacia is not saying how it is implementing this but says the end result is similar to probabilistic shaping. “Instead of 2 or 3 bits-per-symbol, you can be at 2.5 or 2.7 bits-per-symbol,” says Williams. The performance benefits include maximising the link margin and the capacity transmitted over a given link. (See diagram, top.)

The SD-FEC has also been strengthened to achieve a higher coding gain while still being a relatively low-power implementation.

Using a higher baud rate allows a lower order modulation scheme to be used. This can more than double the reach. Source: Acacia

Using a higher baud rate allows a lower order modulation scheme to be used. This can more than double the reach. Source: Acacia

The company says it is restricted in detailing the AC1200’s exact performance. “Because we are a merchant supplier selling into system vendors that do the link implementations, we have to be careful about the reach expectations we set,” says Williams. But the combination of fractional QAM, a tunable baud rate, and improved FEC means a longer reach for a given capacity. And the capacity can be tuned in 50-gigabit increments.

Platforms and status

ADVA Optical Networking is one vendor that has said it is using Acacia’s 1.2-terabit design for its Teraflex product, the latest addition to its CloudConnect family of data centre interconnect products.

Is ADVA Optical Networking using the AC1200? “Our TeraFlex data centre interconnect product uses a coherent engine specifically developed to meet the performance expectations that our customers demand,” says ADVA's spokesperson.

Teraflex is a one-rack-unit (1RU) stackable chassis that supports three hot-pluggable 1.2-terabit ‘sleds’. Each sled’s front panel supports various client-side interface module options: 12 x 100-gigabit QSFP28s, 3 x 400-gigabit QSFP-DDs and lower speed 10-gigabit and 40-gigabit modules using ADVA Optical Networking’s MicroMux technology.

Samples of the AC1200 module will be available in the first half of 2018, says Acacia. General availability will likely follow a quarter or two later.

Oclaro’s 400-gigabit plans

Adam Carter, Oclaro’s chief commercial officer, discusses the company’s 400-gigabit and higher-speed coherent optical transmission plans and the 400-gigabit client-side pluggable opportunity.

Oclaro showcased its first coherent module that uses Ciena’s WaveLogic Ai digital signal processor at the ECOC show held recently in Gothenburg.

Adam CarterOclaro is one of three optical module makers, the others being Lumentum and NeoPhotonics, that signed an agreement with Ciena earlier this year to use the system vendor’s DSP technology and know-how to bring coherent modules to market. The first product resulting from the collaboration is a 5x7-inch board-mounted module that supports 400-gigabits on a single-wavelength.

Adam CarterOclaro is one of three optical module makers, the others being Lumentum and NeoPhotonics, that signed an agreement with Ciena earlier this year to use the system vendor’s DSP technology and know-how to bring coherent modules to market. The first product resulting from the collaboration is a 5x7-inch board-mounted module that supports 400-gigabits on a single-wavelength.

The first WaveLogic Ai-based modules are already being tested at several of Oclaro’s customers’ labs. “They [the module samples] are very preliminary,” says Adam Carter, the chief commercial officer at Oclaro. “The really important timeframe is when we get towards the new year because then we will have beta samples.”

DSP developments

The coherent module is a Ciena design and Carter admits there isn’t going to be much differentiation between the three module makers’ products.

“We have some of the key components that sit inside that module and the idea is, over time, we would design in the rest of the componentry that we make that isn’t already in there,” says Carter. “But it is still going to be the same spec between the three suppliers.”

The collaboration with the module makers helps Ciena promote its coherent DSP to a wider market and in particular China, a market where its systems are not deployed.

Over time, the scope for differentiation between the three module makers will grow. “It [the deal] gives us access to another DSP chip for potential future applications,” says Carter.

Here, Oclaro will be the design authority, procuring the DSP chip for Ciena before adding its own optics. “So, for example, for the [OIF’s] 400G ZR, we would ask Ciena to develop a chip to a certain spec and then put our optical sub-assemblies around it,” says Carter. “This is where we do believe we can differentiate.”

Oclaro also unveiled at ECOC an integrated coherent transmitter and an intradyne coherent receiver optical sub-assemblies using its indium phosphide technology that operate at up to 64 gigabaud (Gbaud).

We expect to see 64Gbaud optical systems being trialed in 2018 with production systems following at the end of next year

A 64Gbaud symbol rate enables a 400-gigabit wavelength using 16-ary quadrature amplitude modulation (16-QAM) and a 600-gigabit wavelength using 64-QAM.

Certain customers want such optical sub-assemblies for their line card designs and Oclaro will also use the building blocks for its own modules. The devices will be available this quarter. “We expect to see 64Gbaud optical systems being trialed in 2018 with production systems following at the end of next year and the beginning of 2019,” says Carter.

Oclaro also announced that its lithium niobate modulator supporting 400-gigabit single wavelengths is now in volume production. “Certain customers do have their preferences when it comes to first designs and particularly for long-reach systems,” says Carter. “Lithium niobate seems to be the one people go with.”

400-gigabit form factors

Oclaro did not make any announcements regarding 400-gigabit client-side modules at ECOC. At the OFC show held earlier this year, it detailed two CFP8-based 400-gigabit designs based on eight wavelengths with reaches of 10km and 40km.

“We are sampling the 400-gigabit 10km product right now,” says Carter. “The product is being tested at the system level and will go through various qualification runs.”

The 40km CFP8 product is further out. There are customers interested in such a module as they have requirements to link IP routers that are more than 10km apart.

Carter describes the CFP8 400-gigabit modules as first-generation products. The CFP8 is similar in size to the CFP2 pluggable module and that is too large for the large-scale data centre players. They want higher aggregate bandwidth and greater front panel densities for their switches and are looking such form factors as the double-density QSFP (QSFP-DD) and the Octal Small Form Factor pluggable (OSFP).

The OSFP is a fresh design, has a larger power envelope - some 15W compared to the 12W of the QSFP-DD - and has a roadmap that supports 800-gigabit data rates. In contrast, the QSFP-DD is backward compatible with the QSFP, an attractive feature for many vendors.

But it is not only a module’s power envelope that is an issue for 400-gigabit designs but also whether a one-rack-unit box can be sufficiently cooled when fully populated to avoid thermal runaway. Some 36 QSFP-DDs can fit on the front panel compared to 32 OSFPs.

Carter stresses both form factors can’t be dismissed for 400-gigabit: “Everyone is pursuing designs that are suitable for both.” Oclaro is not an advocate of either form factor given it provides optical sub-assemblies suitable for both.

The industry really wants four-channels. When you use more lasers, you are adding more cost.

Optical formats

Oclaro’s core technology is indium phosphide and, as such, its focusses on single-mode fibre designs.

The single mode options for 400 gigabits are split between eight-wavelength designs such as the IEEE 802.3bs 2km 400GBASE-FR8 and 10km 400GBASE-LR8 and the newly announced CWDM8 MSA, and four-wavelength specifications - the 500m IEEE 802.3bs parallel fibre 400GBASE-DR4 and the 2km 100G Lambda MSA 400G-FR4 that is under development. Oclaro is a founding member of the 100 Gigabit Lambda MSA but has not joined the CWDM8 MSA.

"The industry really wants four channels," says Carter. "When you use more lasers, you are adding more cost." It is also not trivial fitting eight lasers into a CFP8 never mind into the smaller QSFP-DD and OSFP modules.

“There might be some that have the technology to do the eight-channel part and there might be customers that will use that,” says Carter. “But most of the discussions we’ve been having are around four channels.”

Challenges

The industry’s goal is to have 400-gigabit QSFP-DD and OSFP module in production by the end of next year and into 2019. “There is still some risk but everybody is driving to meet that schedule,” says Carter.

Oclaro says first samples of 100-gigabit PAM-4 chips needed for 100-gigabit single wavelengths are now in the labs. Module makers can thus add their optical sub-assemblies to the chips and start testing system performance. Four-channel PAM-4 chips will be needed for the 400-gigabit module products.

Carter also acknowledges that any further delay in four-wavelength designs could open the door for other 400-gigabit solutions and even interim 200-gigabit designs.

“As a transceiver supplier and an optical component supplier you are always aware of that,” he says. “You have to have backup plans if that comes off.”

The CWDM8 MSA avoids PAM-4 to fast-track 400G

Another multi-source agreement (MSA) group has been created to speed up the market introduction of 400-gigabit client-side optical interfaces.

The CWDM8 MSA is described by its founding members as a pragmatic approach to provide 400-gigabit modules in time for the emergence of next-generation switches next year. The CWDM8 MSA was announced at the ECOC show held in Gothenburg last week.

Robert BlumThe eight-wavelength coarse wavelength-division multiplexing (CWDM) MSA is being promoted as a low-cost alternative to the IEEE 803.3bs 400 Gigabit Ethernet Task Force’s 400-gigabit eight-wavelength specifications, and less risky than the newly launched 100G Lambda MSA specifications based on four 100-gigabit wavelengths for 400 gigabit.

Robert BlumThe eight-wavelength coarse wavelength-division multiplexing (CWDM) MSA is being promoted as a low-cost alternative to the IEEE 803.3bs 400 Gigabit Ethernet Task Force’s 400-gigabit eight-wavelength specifications, and less risky than the newly launched 100G Lambda MSA specifications based on four 100-gigabit wavelengths for 400 gigabit.

“The 100G Lambda has merits and we are also part of that MSA,” says Robert Blum, director of strategic marketing and business development at Intel’s silicon photonics product division. “We just feel the time to get to 100-gigabit-per-lambda is really when you get to 800 Gigabit Ethernet.”

Intel is one of the 11 founding companies of the CWDM8 MSA.

Specification

The CWDM8 MSA will develop specifications for 2km and 10km links. The MSA uses wavelengths spaced 20nm apart. As a result, unlike the IEEE’s 400GBASE-FR8 and 400GBASE-LR8 that use the tightly-spaced LAN-WDM wavelength scheme, no temperature control of the lasers is required. “It is just like the CWDM4 but you add four more wavelengths,” says Blum.

The CWDM8 MSA also differs from the IEEE specifications and the 100G Lambda MSA in that it does not use 4-level pulse-amplitude modulation (PAM-4). Instead, 50-gigabit non-return-to-zero (NRZ) signalling is used for each of the eight wavelengths.

The MSA will use the standard CDAUI-8 8x50-gigabit PAM-4 electrical interface. Accordingly, a retimer chip will be required inside the module to translate the input 50-gigabit PAM electrical signal to 50-gigabit NRZ. According to Intel, several companies are developing such a chip.

When we looked at what is available and how to do an optical interface, there was no good solution that would allow us to meet those timelines

Benefits

Customers are telling Intel that they need 400-gigabit duplex-fibre optical modules early next year and that they want to have them in production by the end of 2018.

“When we looked at what is available and how to do an optical interface, there was no good solution that would allow us to meet those timelines, fit the power budget of the QSFP-DD [module] and be at the cost points required for data centre deployment,” says Blum.

An 8x50-gigabit NRZ approach is seen as a pragmatic solution to meet these requirements.

No PAM-4 physical layer DSP chip is needed since NRZ is used. The link budget is significantly better compared to using PAM-4 modulation. And there is a time-to-market advantage since the technologies used for the CWDM8 are already proven.

We just think it [100-gigabit PAM4] is going to take longer than some people believe

This is not the case for the emerging 100-gigabit-per-wavelength MSA that uses 50-gigabaud PAM-4. “PAM-4 makes a lot of sense on the electrical side, a low-bandwidth [25 gigabaud], high signal-to-noise ratio link, but it is not the ideal when you have high bandwidth on the optical components [50 gigabaud] and you have a lot of noise,” says Blum.

One-hundred-gigabit-per-wavelength will be needed for the optical path, says Blum, but for 800 Gigabit Ethernet with its eight electrical channels and eight optical ones. “We just think it [100-gigabit PAM4] is going to take longer than some people believe.” Meanwhile, the CWDM8 is the best approach to meet market demand for a 400-gigabit duplex interfaces to support next-generation data centre switches expected next year, says Blum.

The founding members of the CWDM8 MSA include chip and optical component players as well as switch system makers. Unlike the 100G Lambda MSA, no larger-scale data centre operators have joined the MSA.

The members are Accton, Barefoot Networks, Credo Semiconductor, Hisense, Innovium, Intel, MACOM, Mellanox, Neophotonics and Rockley Photonics.

MultiPhy unveils 100G single-wavelength PAM-4 chip

A chip to enable 100-gigabit single-wavelength client-side optical modules has been unveiled by MultiPhy. The 100-gigabit 4-level pulse amplitude modulation (PAM-4) circuit will also be a key building block for 400 Gigabit Ethernet interfaces that use four wavelengths.

Source: MultiPhy

Source: MultiPhy

Dubbed the MPF3101, the 100-gigabit physical layer (PHY) chip is aimed at such applications as connecting switches within data centres and for 5G cloud radio access network (CRAN).

“The chip has already been sent out to customers and we are heading towards market introductions,” says Avi Shabtai, CEO of MultiPhy.

The MPF3101 will support 100-gigabit over 500m, 2km and 10km.

The IEEE has developed the 100-gigabit 100GBASE-DR standard for 500m while the newly formed 100G Lambda MSA (multi-source agreement) is developing specifications for the 2km 100-gigabit single-channel 100G-FR and the 10km 100G-LR.

MultiPhy says the QSFP28 will be the first pluggable module to implement a 100-gigabit single-wavelength design using its chip. The SFP-DD MSA, currently under development, will be another pluggable form factor for the single-wavelength 100-gigabit designs.

The chip has already been sent out to customers and we are heading towards market introductions

400 Gigabit

The 100-gigabit IP will also be a key building block for a second MultiPhy chip for 400-gigabit optical modules needed for next-generation data centre switches that have 6.4 and 12.8 terabits of capacity. “This is the core engine for all these markets,” says Shabtai.

Companies have differing views as to how best to address the 400-gigabit interconnect market. There is a choice of form factors such as the OSFP, QSFP-DD and embedded optics based on the COBO specification, as well as emerging standards and MSAs.

The dilemma facing companies is what approach will deliver 400-gigabit modules to coincide with the emergence of next-generation data centre switches.

One consideration is the technical risk associated with implementing a particular design. Another is cost, with the assumption that 4-wavelength 400-gigabit designs will be cheaper than 8x50-gigabit based modules but that they may take longer to come to market.

For 400 gigabits, the IEEE 803.3bs 400 Gigabit Ethernet Task Force has specified the 400GBASE-DR4, a 500m-reach four-wavelength specification that uses four parallel single-mode fibres. The 100G Lambda MSA is also working on a 400-gigabit 2km specification based on coarse wavelength-division multiplexing (CWDM), known as 400G-FR4, with work on a 10km reach specification to start in 2018.

We are hearing a lot in the industry about 50-gigabit-per-lambda. For us, this is old news; we are moving to 100-gigabit-per-lambda and we believe the industry will align with us.

And at ECOC 2017 show, held last week in Gothenburg, another initiative - the CWDM8 MSA - was announced. The CWDM8 is an alternative design to the IEEE specifications that sends eight 50-gigabit non-return-to-zero signals rather that PAM-4 over a fibre.

“We are hearing a lot in the industry about 50-gigabit-per-lambda,” says Shabtai. “For us, this is old news; we are moving to 100-gigabit-per-lambda and we believe the industry will align with us.”

Chip architecture

The MPF3101, implemented using a 16nm CMOS process, supports PAM-4 at symbol rates up to 58 gigabaud.

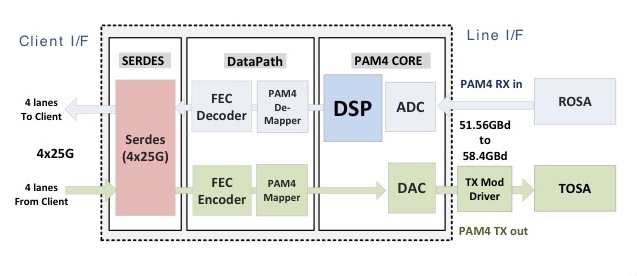

The chip’s electrical input is four 25-gigabit lanes that are multiplexed and encoded into a 50-plus gigabaud PAM-4 signal that is fed to a modulator driver, part of a 100-gigabit single-channel transmitter optical sub-assembly (TOSA). A 100-gigabit receiver optical sub-assembly (ROSA) feeds the received PAM-4 encoded signal to the chip’s DSP before converting the 100-gigabit signal to 4x25 gigabit electrical signals (see diagram).

“If you need now only one laser and one optical path [for 100 gigabits] instead of four [25 gigabits optical paths], that creates a significant cost reduction,” says Shabtai.

The advent of a single-wavelength 100-gigabit module promises several advantages to the industry. One is lower cost. Estimates that MultiPhy is hearing is that a single-wavelength 100-gigabit module will be half the cost of existing 4x25-gigabit optical modules. Such modules will also enable higher-capacity switches as well as 100-gigabit breakout channels when connected to a 400-gigabit four-wavelength module. Lastly, MultiPhy expects the overall power consumption to be less.

Availability

MultiPhy says first 100-gigabit single-wavelength QSFP28s will appear sometime in 2018.

The company is being coy as to when it will have a 400-gigabit PAM-4 chip but it points out that by having working MPF3101 silicon, it is now an integration issue to deliver a 4-channel 400-gigabit design.

As for the overall market, new high-capacity switches using 400-gigabit modules will start to appear next year. The sooner four-channel 400-gigabit PAM-4 silicon and optical modules appear, the less opportunity there will be for eight-wavelength 400-gigabit designs to gain a market foothold.

“That is the race we are in,” says Shabtai.