Video compression: Tackling at source traffic growth

The issue is the same whether it is IPTV services and over-the-top video sent over fixed networks, or video transmitted over 3G wireless networks or even video distributed within the home.

According to Cisco Systems, video traffic will become the dominant data traffic by 2013. Any technology that trims the capacity needed for video streams is thus to be welcomed.

"The algorithm uses a combination of maths and how images are perceived to filter out what is not needed while keeping the important information.

Angel DeCegama, ADC2 Technologies

Massachusetts-based start-up ADC2 Technologies (ADC2 stands for advanced digital compression squared) has developed a video processing technology that works alongside existing video coder/decoders (codecs) such as MPEG-4 and H-264 to deliver a 5x compression improvement.

ADC2 uses wavelet technology; a signal processing technique that for this application extracts key video signal information. “We pre-process video before it is fed to a standard codec,” says Angel DeCegama, CEO and CTO of ADC2 Technologies. “The algorithm uses a combination of maths and how images are perceived to filter out what is not needed while keeping the important information.”

The result is a much higher compression ratio than if a standard video codec is used alone. At the receiving end the video is decoded using the codec and then restored using ADC2’s post-processing wavelet algorithm.

DeCegama says the algorithm scales by factors of four but that any compression ratio between 2x to 8x can be used. As for the processing power required to implement the compression scheme, DeCegama says that a quad-core Intel processor can process a 2Gbit/s video stream.

ADC2 Technologies envisages several applications for the wavelet technology. Added to a cable or digital subscriber line (DSL) modem, operators could deliver IPTV more efficiently. And if the algorithm is included in devices such as set-top boxes and display screens, it would enable efficient video transmission within the home.

The technology can also be added to smart phones with the required wavelet processing executed on the phone's existing digital signal processing hardware. More video transmissions could be accommodated within the wireless cell and more video could be sent from phones via the upstream link.

ADC2 Technologies demonstrated the technology at the Supercomm trade show held in Chicago in October. Established in 2008, the 5-staff start-up is looking to develop hardware prototypes to showcase the technology.

The first market focus for the company is content delivery. Using its technology, operators could gain a fivefold improvement in network capacity when sending video. Meanwhile end users could receive more high-definition video streams as well as greater content choice. “Everyone benefits yet besides some extra hardware and/or software in the home, the network infrastructure remains the same,” says DeCegama.

Digital Home: Services, networking technologies and challenges facing operators

Source: Microsoft

Source: Microsoft

The growth of internet-enabled devices and a maturing of networking technologies indicate the digital home is entering a new phase. But while operators believe the home offers important new service and revenue opportunities, considerable challenges remain. Operators are thus proceeding cautiously.

Here is a look at the status of the digital home in terms of:

- Services driving home networking

- Wireless and wireline home networking technologies

- Challenges

Services driving home networking

IPTV and video delivery are key services that place significant demands on the home network in terms of bandwidth and reach. Typically the residential gateway that links the home to the broadband network, and the set-top box where video is consumed are located apart. Connecting the two has been a challenge for telcos. In contrast, cable operators (MSOs) have always networked video around the home. The MSOs’ challenge is adding voice and linking home devices such as PCs.

Now the telcos are meeting the next challenge: distributing video between multiple set-tops and screens in the home.

Other revenue-generating home services interesting service providers include:

- A contract to support a subscriber’s home network

- E-health: remote monitoring a patient’s health

- Home security using video cameras

- Media content: enabling a user to grab home-stored content when on the move

- Smart meters and energy management

One development that operators cannot ignore is ‘over-the-top’ services. Users can get video from third parties directly over the internet. Such over-the-top services are a source of competition for operators and complicate home networking requirements in that users can buy and connect their own media players and internet-enabled TVs. Yet any connectivity issues and it is the operator that will get the service call.

However, over-the-top services are also an opportunity in that they can be integrated as part of the operator’s own offerings and delivered with quality of service (QoS).

Wireless and wireline home networking technologies

Operators face a daunting choice of networking technologies. Moreover, no one technology promises complete, reliable home coverage due to wireless signal fades or wiring that is not where it is needed.

As a result operators must use more than one networking technology. Within wireline there are over half a dozen technology options available. And even for a particular wireline technology, power line for example, operators have multiple choices.

Wireless:

- Wi-Fi is the technology of choice with residential gateway vendors now supporting the IEEE 802.11n standard which extends the data rate to beyond 100 megabits-per-second (Mbps). An example is Orange’s Livebox2 home gateway, launched in June 2009.

- The second wireless option is femtocells, that is now part of the define features of the Home Gateway Initiative’s next-generation (Release 3) platform, planned for 2010. Mass deployment of femtocells is still to happen and will only serve handsets and consumer devices that are 3G-enabled.

Wireline

- If new wiring of a home is possible, operators can use Ethernet Category-5 cabling, or plastic optical fibre (POF) which is flexible and thin.

- More commonly existing home wiring like coaxial cable, electrical wiring (powerline) or telephone wiring is used. Operators have adopted HomePNA which supports phone wiring; the Multimedia over Coax Alliance (MoCA) that uses coaxial cabling; and the HomePlug Powerline Alliance’s HomePlug AV, a powerline technology that uses a home’s power wiring over which data is transmitted.

- Gigabit home networking (G.hn) is a new standard being developed by the International Telecommunication Union. Set to appear in products in 2010, the standard can work over three wireline media: phone, coax and powerline. AT&T, BT and NTT are backing G.hn though analysts question its likely impact overall. Indeed one operator says the emerging standard could further fragment the market.

Challenges

- Building a home network is complex due to the many technologies and protocols involved.

- Users have an expectation that operators will solve their networking issues yet operators only own and are interested in their own home equipment: the gateway and set-top box. Operators risk getting calls from frustrated users that have deployed a variety of consumer devices. Such calls impact the operators’ bottom line.

- Effective tools and protocols for home networking monitoring and management is a must for the operators. The Broadband Forum’s TR-069 and the Universal Plug and Play (UPnP) diagnostic and QoS software protocols continue to evolve but so far only a fraction of their potential is being used.

Operators understandably are proceeding with care as they cross the home's front door to ensure their offerings are simple and reliable. Otherwise any revenue-potential home networking promises as well as a long-term relationship with the subscriber will be lost.

To read more:

- A full article including interviews with operators BT and Orange; vendors Cisco Systems, Alcatel-Lucent’s Motive division, Ericsson and Netgear; chip vendors Gigle Semiconductor and Broadcom; the Home Gateway Initiative and analysts Parks Associates, TelecomView and ABI Research will appear in the January 2010 issue of Total Telecom.

- Can residential broadband services succeed without home network management? Analysys Mason’s Patrick Kelly.

Mind maps

To download the full mind map in .pdf form, click here.

Active optical cable: market drivers

CIR’s report key findings

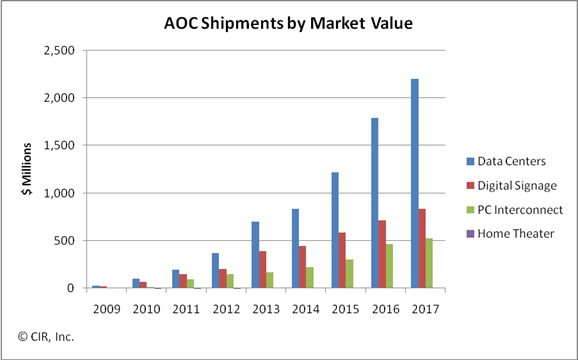

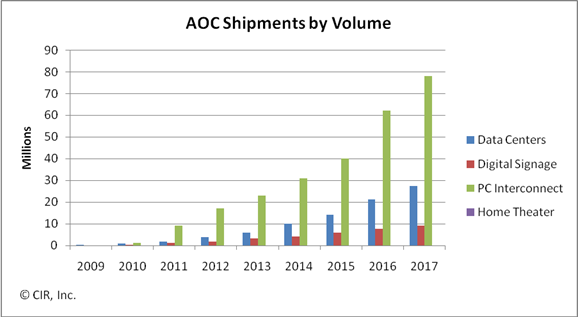

The global market for active optical cable (AOC) is forecast to grow to US $1.5bn by 2014, with the linking of datacenter equipment being the largest single market valued at $835m. Other markets for the cabling technology include digital signage, PC interconnect and home theatre.

CIR’s report entitled Active Optical Cabling: A Technology Assessment and Market Forecast notes how AOC emerged with a jolt. Two years on and the technology is now a permanent fixture that will continue to nimbly address application as they appear. This explains why CIR views AOC as an opportunistic and tactical interconnect technology.

AOC: "Opportunistic and tactical"

Loring Wirbel

What is active optical cable?

An AOC converts an electrical interface to optical for transmission across a cable before being restored to the electrical domain. Optics are embedded as part of the cabling connectors with AOC vendors using proprietary designs. Being self-contained, AOCs have the opportunity to become a retail sale at electronics speciality stores.

A common interface for AOC is the QSFP but there are AOC products that use proprietary interfaces. Indeed the same interface need not be used at each end of the cable. Loring Wirbel, author of the CIR AOC report, mentions a MergeOptics’ design that uses a 12-channel CXP interface at one end and three 4-channel QSFP interfaces at the other. “If it gets traction, everyone will want to do it,” he says.

Origins

AOC products were launched by several vendors in 2007. Start-up Luxtera saw it as an ideal entry market for its silicon photonics technology; Finisar came out with a 10Gbps serial design; while Zarlink identified AOC as a primary market opportunity, says Wirbel.

Application markets

AOC is the latest technology targeting equipment interconnect in the data centre. Typical distances linking equipment range from 10 to 100m; 10m is where 10Gbps copper cabling starts to run out of steam while 100m and above are largely tackled by structured cabling.

“Once you get beyond 100 meters, the only AOC applications I see are outdoor signage and maybe a data centre connecting to satellite operations on a campus,” says Wirbel.

AOC is used to connect servers and storage equipment using either Infiniband or Ethernet. “Keep in mind it is not so much corporate data centres as huge dedicated data centre builds from a Google or a Facebook,” says Wirbel.

AOC’s merits include its extended reach and light weight compared to copper. Servers can require metal plates to support the sheer weight of copper cabling. The technology also competes with optical pluggable transceivers and here the battleground is cost, with active optical cabling including end transceivers and the cable all-in-one.

To date AOC is used for 10Gbps links and for double data rate (DDR) and quad data rate (QDR) Infiniband. But it is the evolution of Infiniband’s roadmap - eight data rate (EDR, 20Gbps per lane) and hexadecimal data rate (HDR, 40Gbps per lane) - as well as the advent of 100m 40 and 100 Gigabit Ethernet links with their four and ten channel designs that will drive AOC demand.

The second largest market for AOC, about $450 million by 2014, and one that surprised Wirbel, is the ‘unassuming’ digital signage.

Until now such signs displaying video have been well served by 1Gbps Ethernet links but now with screens showing live high-definition feeds and four-way split screens 10Gbps feeds are becoming the baseline. Moreover distances of 100m to 1km are common.

PC interconnect is another market where AOC is set to play a role, especially with the inclusion of a high-definition multimedia interface (HDMI) interface as standard with each netbook.

“A netbook has no local storage, using the cloud instead,” says Wirbel. Uploading video from a video camera to the server or connecting video streams to a home screen via HDMI will warrant AOC, says Wirbel.

Home theatre is the fourth emerging application for AOC though Wirbel stresses this will remain a niche application.

Optical transceivers: Useful references

Industry bodies

The CFP Multi-Source Agreement (MSA): The hot-pluggable optical transceiver form factor for 40Gbps and 100Gbps applications

Useful articles on optical transceivers

- CFP, CXP form factors complementary, not competitive, Lightwave magazine

- The difference between CFP and CXP, Lightspeed blog

|

Company |

Comment |

|

System vendors |

|

|

ZTE |

ZXR10 T8000 core router with up to 2,048 40Gbps or 1,024 100Gbps interfaces |

|

|

|

|

Optical transceivers |

|

|

Finisar |

40GBASE-LR4 CFP: A 40 Gigabit Ethernet (GbE) LR4 CFP transceiver |

|

Opnext |

100GBASE-LR4 CFP: The 100GbE optical transceiver standard for 10km. Sept 2009. |

|

Reflex Photonics |

Dual 40Gbps CFP: Two 40GBASE-SR4 specification for 40G Ethernet links up to 150m. Oct 2009 |

|

Sumitomo Electric |

40GBASE-LR4: The 40GbE CFP module for 10km transmission. Sept 2009 |

|

Menara Networks |

XFP OTN |

Table 1: Company announcements

AT&T rethinks its relationship with networking vendors

“We’ll go with only two players [per domain] and there will be a lot more collaboration.”

Tim Harden, AT&T

AT&T has changed the way it selects equipment suppliers for its core network. The development will result in the U.S. operator working more closely with vendors, and could spark industry consolidation. Indeed, AT&T claims the programme has already led to acquisitions as vendors broaden their portfolios.

The Domain Supplier programme was conjured up to ensure the financial health of AT&T’s suppliers as the operator upgrades its network to all-IP.

By working closely with a select group of system vendors, AT&T will gain equipment tailored to its requirements while shortening the time it takes to launch new services. In return, vendors can focus their R&D spending by seeing early the operator’s roadmap.

“This is a significant change to what we do today,” says Tim Harden, president, supply chain and fleet operations at AT&T. Currently AT&T, like the majority of operators, issues a request-for-proposal (RFP) before getting responses from six to ten vendors typically. A select few are taken into the operator’s labs where the winning vendor is chosen.

With the new programme, AT&T will work with players it has already chosen. “We’ll go with only two players [per domain] and there will be a lot more collaboration,” says Harden. “We’ll bring them into the labs and go through certification and IT issues.” Most importantly, operator and vendor will “interlock roadmaps”, he says.

The ramifications of AT&T’s programme could be far-reaching. The promotion of several broad-portfolio equipment suppliers into an operator’s inner circle promises them a technological edge, especially if the working model is embraced by other leading operators.

The development is also likely to lead to consolidation. Equipment start-ups will have to partner with domain suppliers if they wish to be used in AT&T’s network, or a domain supplier may decide to bring the technology in-house.

Meanwhile, selling to domain supplier vendors becomes even more important for optical component and chip suppliers.

Domain suppliers begin to emerge

AT&T first started work on the programme 18 months ago. “AT&T is on a five-year journey to an all-IP network and there was a concern about the health of the [vendor] community to help us make that transition, what with the bankruptcy of Nortel,” says Harden. The Domain Supplier programme represents 30 percent of the operator’s capital expenditure.

The operator began by grouping technologies. Initially 14 domains were identified before the list was refined to eight. The domains were not detailed by Harden but he did cite two: wireless access, and radio access including the packet core.

For each domain, two players will be chosen. “If you look at the players, all have strengths in all eight [domains],” says Harden.

AT&T has been discussing its R&D plans with the vendors, and where they have gaps in their portfolios. “You have seen the results [of such discussions] being acted out in recent weeks and months,” says Harden, who did not name particular deals.

In October Cisco Systems announced it planned to acquire IP-based mobile infrastructure provider Starent Networks, while Tellabs is to acquire WiChorus, a maker of wireless packet core infrastructure products. "We are not at liberty to discuss specifics about our customer AT&T,” says a Tellabs spokesperson. Cisco has still to respond.

Harden dismisses the suggestion that its programme will lead to vendors pursuing too narrow a focus. Vendors will be involved in a longer term relationship – five years rather than two or three common with RFPs, and vendors will have an opportunity to earn back their R&D spending. “They will get to market faster while we get to revenue faster,” he says.

The operator is also keen to stress that there is no guarantee of business for a vendor selected as a domain supplier. Two are chosen for each domain to ensure competition. If a domain supplier continues to meet AT&T’s roadmap and has the best solution, it can expect to win business. Harden stresses that AT&T does not require a second-supplier arrangement here.

In September AT&T selected Ericsson as one of the domain suppliers for wireline access, while suppliers for radio access Long Term Evolution (LTE) cellular will be announced in 2010.

WDM-PON: Can it save operators over €10bn in total cost of ownership?

Source: ADVA Optical Networking

Source: ADVA Optical Networking

“The focus of operators to squeeze the last dollar out of the system and optical component vendors is really nonsense.”

Klaus Grobe, ADVA Optical Networking.

Key findings

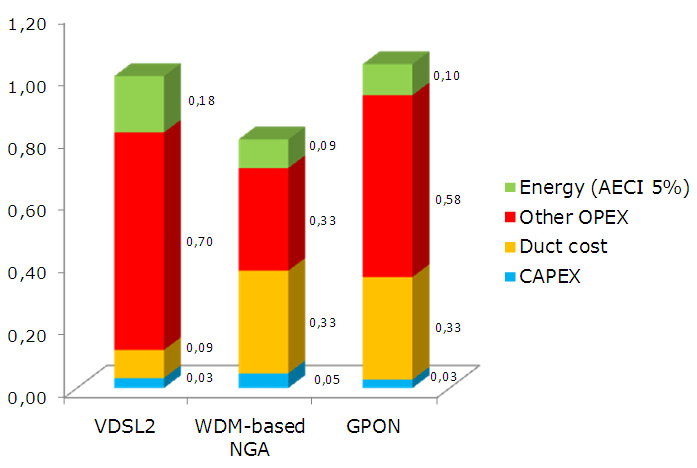

The total cost of ownership (TCO) of a widely deployed WDM-PON network is at least 20 percent cheaper than the broadband alternatives of VDSL and GPON. Given that the cost of deploying a wide-scale access network in a large western European country is €60bn, a 20 percent cost saving is huge, even if spread over 25 years.

What was modelled?

ADVA Optical Networking wanted to quantify the TCO of three access schemes: wavelength-division-multiplexing passive optical networking (WDM-PON), gigabit PON (GPON) - the PON scheme favoured by European incumbents, and copper-based VDSL (very high bit-rate digital subscriber line).

The company modelled a deployment serving 1 million residences and 10,000 enterprises. “We took seriously the idea of broadband roll out especially when operators talk about it being a strategic goal,” says Klaus Grobe, principal engineer at ADVA Optical Networking. “We wanted a single number that says it all.”

Assumptions

ADVA Optical Networking splits the TCO into four categories:

- Duct cost

- Other operational expense (OpEx)

- Energy consumption

- Capital expenditure (CapEx)

For ducting, it is assumed that VDSL already has fibre to the cabinet and the copper linking the user, whereas for optical access - WDM-PON and GPON - the feeder fibre is present but distribution fibre must be added to connect each home and enterprise. “There is also a certain upgrade of the feeder fibre required but it is 5 percent of the distribution fibre costs,” says Grobe. Hence the ducting costs of GPON and WDM-PON are similar and higher than VDSL.

A 25-year lifetime was also used for the TCO analysis during which three generations of upgrades are envisaged. For the end device like a PON optical network unit (ONU) the cost is the same for each generation, even if performance is significant improved each time.

The ‘other OpEx’ includes all the elements of OpEx except energy costs. The category includes planning and provisioning; operations, administration and maintenance (OA&M); and general overhead.

Planning and provisioning, as the name implies, covers the planning and provisioning of system links and bandwidth, says Grobe. Also the WDM-PON network serves both residential and enterprises whereas duplicate networks are required for GPON and VDSL, adding cost.

The ‘general overheads’ category includes an operator’s sales department. Grobe admits there is huge variation here depending on the operator and thus a common figure for all three cases was used.

Energy consumption is clearly important here. Three annual energy cost increase (AECI) rates were explored – 2, 5 and 10 percent (shown in the chart is the 5% case), with a cost of 80 €/MWh assumed for the first year.

The energy cost savings for WDM-PON come not from the individual equipment but from the reduced number of sites deploying the access technology allows. The power consumed of a WDM-PON ONU is 1W, greater than VDSL, says Grobe, but a lot more local exchanges and cabinets are used for VDSL than for WDM-PON.

And this is where the biggest savings arise: the difference in OA&M due to there being fewer sites for WDM-PON than for GPON and VDSL. That’s because WDM-PON has a larger, up to 100km, reach from the central office to the end user. And, as mentioned, a WDM-PON network caters for enterprise and residential users whereas GPON and VDSL require two distinct networks. This explains the large differences between VDSL, GPON and WDM-PON in the ‘other OpEX’ category.

Grobe says it is difficult to estimate the site reduction deploying WDM-PON will deliver. Operators are less forthcoming with such figures. However, the model and assumptions have been presented to operators and no objections were raised. Equally, the model is robust – varying wildly any one parameter does not change the main findings of the model.

Lastly, for CapEx, WDM-PON equipment is, as expected, the most expensive. CapEx for all three cases, however, is by far the smallest contributor to TCO.

Mass roll outs on the way?

So will operators now deploy WDM-PON on a huge scale? Sadly no, says Grobe. Up-front costs are paramount in operators’ thinking despite the vast cost saving if the lifetime of the network is considered.

But the analysis highlights something else for Grobe that will resonate with the optical community. “The focus of operators to squeeze the last dollar out of system and optical component vendors is really nonsense,” he says.

See ADVA Optical Networking's White Paper

See an associated presentation

Optical industry drivers and why gazettabyte

An interview on Finisar's Lightspeed blog.

A bit more about gazettabyte in Write Thinking

And gazettabyte making news

Photonic integration: Bent on disruption

“This is a general rule: what starts as a series of parts loosely strung together, if used heavily enough, congeals into a self-contained unit.”

W. Brian Arthur, The Nature of Technology

Infinera's Dave Welch: PICs are fibre-optic's current disruption

Infinera's Dave Welch: PICs are fibre-optic's current disruption

Dave Welch likes to draw a parallel with digital photography when discussing the use of photonic integration for optical networking. “The CMOS photodiode array – a photonic integrated circuit - changed the entire supply chain of photography,” says Welch, the chief strategy officer at Infinera.

Applied to networking, the photonic integrated circuit (PIC) is similar, argues Welch. It benefits system cost by integrating individual optical components but it delivers more. “All the value – inherently harder to pin down - of networking efficiency of a system that isn’t transponder-based,” says Welch.

Just how disruptive a technology the PIC proves to be is unclear but there is no doubting the growing role of optical integration.

“Integration is a key part of our thinking,” says Sam Bucci, vice president, WDM, Alcatel-Lucent’s optics activities. When designing a new platform, Alcatel-Lucent surveys components and techniques to identify disruptive technologies. Even if it chooses to implement functions using discrete components, the system is designed taking into account future integrated implementations.

“We are seeing interest [in photonic integration] across the spectrum," says Stefan Rochus, vice president of marketing and business development at CyOptics. "Long-haul, metro, access and chip-to-chip - everything is in play."

The drivers for optical integration’s greater use are harder to pin down.

Operators must contend with yearly data traffic growth estimated at between 45 to 65 percent yet their revenues are growing modestly. “It’s no secret that the capacity curve - whether the line side or the client side - is growing at an astonishing clip,” says Bucci.

The onus is thus on equipment and component makers to deliver platforms that reduce the transport cost per bit."Delivering more for less," says Graeme Maxwell, vice president of hybrid integration at CIP Technologies. “Space is a premium, power is an issue, operators want performance maintained or improved – all are driving integration.”

Cost is an issue for optical components with yearly price drops of 20 percent being common. “Hitting the cost-curve, we have run out of ways to do that with classic optics,” says Sinclair Vass, commercial director, EMEA at JDS Uniphase.

High-speed optical transmission at 40 and 100 Gigabit per second (Gbps) requires photonic integration though here the issues are as much performance as cost reduction. Indeed, its use can be viewed as the result of the integration between electronics and optics. To address optical signal impairments, chips must work at the edge of their performance, requiring the optical signal to be split into slower, parallel streams. Such an arrangement is ripe for photonic integration.

“It is as if there are two kinds of integration: at the boundary between optics and electronics, and the purely optical planar waveguide stuff,” says Karen Liu, vice president, components and video technologies at market research firm Ovum.

The other market where the full arsenal of optical integration techniques – hybrid and monolithic integration – is being applied is optical transceivers for passive optical networking (PON). Here the sole story is cost.

As old as the integrated circuit

Photonic integration is not new. The idea was first mooted in a 1969 AT&T Bell Labs’ paper that described how multiple miniature optical components could be interconnected via optical waveguides made using thin-film dielectric materials. But so far industry adoption for optical networking has been limited.

"Two kinds of integration: at the boundary between optics and electronics, and the purely optical planar waveguide stuff"

Karen Liu, Ovum

Heavy Reading, in a 2008 report, highlighted the limited progress made in photonic integration in recent years, with the exception of Infinera, a maker of systems based on a dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) 10x10Gbps monolithically integrated PIC.

“Infinera has held very consistently to its original story, including sub-wavelength grooming, and have made progress over time,” says Liu. But she points out a real disruptive impact has not yet been seen: “The problem with the digital camera analogy is that something that is disruptive is not a straight replacement but implies the next step: changing the network architecture, not just how a system is implemented.”

On-off keying to phase modulation

One way operators are accommodating traffic growth is cramming more data down a fibre. It is this trend- from 10Gbps to 40 and 100Gbps lightpaths - that is spurring photonic integration.

“If you look at current 100 Gigabit, it is a bigger configuration than we would like,” says Joe Berthold, Ciena’s vice president of network architecture. Ciena’s first 100Gbps design requires three line cards, taking five inches of rack space, while its second-generation design will fit on a single, two-inch card.

Both 40 and 100Gbps transmissions must also operate over existing networks, matching the optical link performance of 10Gbps despite dispersion being more acute at higher line speeds. To meet the challenge, the industry has changed how it modulates data onto light. Whereas previous speed increments up to 10Gbps used simple on-off keying, 40 and 100Gbps use advanced modulation schemes based on phase, or phase combined with polarisation.

The modulation schemes split the optical signal into parallel paths to lower symbol rates. For example, 40Gbps differential quadrature phase-shift keying (DQPSK) uses two signals that effectively operating at 20 Gigabaud. Halving the rate relaxes the high-speed electronics requirements at the expense of complicating the optical circuitry.

The concept is extended further at 100Gbps. Here polarisation is combined with phase modulation (either DQPSK, or QPSK if coherent detection is used) such that four signals are used in parallel, each operating at 28 Gigabaud.

“The 40/100G area is shaping up to be the equivalent of breaking the sound barrier”

Brad Smith, LightCounting

“Optical integration is becoming a necessity because of 40 and 100 Gigabit [transmission],” says Berthold. “The modulation formats require you to deal with signals in parallel, and using non-integrated components explodes the complexity.”

The Optical Internetworking Forum organisation has chosen dual-polarisation QPSK (DP- QPSK) as the favoured modulation scheme for 100Gbps and has provided integrated transmitter and receiver module guidelines to encourage industry convergence on common components. In contrast, for 40Gbps several designs have evolved: differential phase-shift keying (DPSK) through to DQPSK and DP-QPSK.

Kim Roberts, Nortel's director of optics research, while acknowledging that optical integration benefits system footprint and cost, downplays its overall significance.

For him, the adoption of coherent systems for 40 and 100Gbps – Nortel was first to market with a 40Gbps DP-QPSK system – move the complexity ‘into CMOS’, leaving optics to perform the basic functions. “I don’t see an overwhelming argument for integration,” says Roberts. “It’s useful and shows up in lower cost and smaller designs but it’s not a revolution.”

Meanwhile, optical component companies are responding by integrating various building blocks to address the bulkier 40 and 100Gbps designs.

NeoPhotonics is now shipping two PICs for 40 and 100Gbps receivers: a DQPSK demodulator based on two delay-line interferometers (DLIs) and a coherent mixer for a DP-QPSK receiver.

The DLI, as implied by the name, delays one of the received symbols and compares it with the adjacent received one to uncover the phase-encoded information. This is then fed to a balanced detector - a photo-detector pair. For DQPSK, either two DLIs or a single DLI plus 90-degree hybrid are required along with two balanced receivers.

For 100Gbps, a DP-QPSK receiver has four channels - a polarisation beam splitter separates the two polarisations and each component is mixed with a component from a local reference signal using a 90-degree hybrid mixer. The two hybrid mixers decompose the referenced phase to intensity outputs representing the orthogonal phase components of the signal and the four differential outputs are fed into the four balanced detectors (Click here for OIF document and see Fig 5).

Neophotonics’ coherent mixer integrates monolithically all the demodulation functions between the polarisation beam splitter and the balanced photo-detectors.

The company has both indium phosphide and planar lightwave circuit (PLC) technology integration expertise but chose to implement its designs using PLC technology. “Indium phosphide is good for actives but is not good for passives and it is very expensive,” says Ferris Lipscomb, vice president of marketing at NeoPhotonics.

One benefit of using PLC for demodulation is that the signal path lengths need to have sub-millimeter accuracy to recover phase; implementing a discrete design using fibre to achieve such accuracy is clearly cumbersome.

Another development that reduces size and cost involves the teaming of u2t Photonics, a high-speed photo-detector and indium phosphide specialist, with Optoplex and Kylia, free-space optics DLI suppliers. The result is a compact DPSK receiver that combines the DLI and balanced receiver within one package. Such integration at the package level reduces the size since fibre routeing between separate DLI and detector packages is no longer needed. The receiver also cuts cost by a quarter, says u2t.

Jens Fiedler, vice president sales and marketing at u2t Photonics, acknowledges that the free-space DLI design may not be the most compact design but was chosen based on the status of the various technologies. “We needed to provide a solution and PLC was not ready,” he says.

u2t Photonics is investigating a waveguide-based DLI solution and is considering indium phosphide and, intriguingly, gallium arsenide. “Indium phosphide has the benefit of integrating the DLI with the balanced detector,” says Fiedler. “There are benefits but also technical challenges [with indium phosphide].”

At ECOC 2009 in September, u2t announced a multi-source agreement (MSA) with another detector specialist, Picometrix, which supports the OIF’s DP-QPSK coherent receiver design. The MSA defines the form factor, pin functions and locations, and functionality of the receiver package holding the balanced detectors, targeted at transponder and line card designs.

Photonic integration for high-speed transmissions is not confined to the receiver. Oclaro has developed a 40Gbps DQPSK monolithic modulator. Implemented in indium phosphide, the modulator could even be monolithically integrated with the laser but Oclaro has said that there are performance benefits such as signal strength in keeping the two separate.

Infinera, meanwhile, eschews transponders in favour of its 100Gbp indium phosphide-based PIC.

Take your PIC

Take your PIC

In September it announced a system for submarine transmission, achieved by adding a semiconductor optical amplifier (SOA) to its 10-channel transmitter and receiver PIC pair. “We are now at a point when the performance of the PIC is a good as the performance of discretes,” says Welch.

In March the company announced its next-gen PIC design - a 10x40Gbps DP-DQPSK transmitter and receiver chip pair. This is a significantly more complex design, with the transmitter integrating the equivalent of 300 optical functions; Infinera’s 10x10G transmitter PIC integrates 50.

Infinera favoured DP-DQPSK rather than the OIF-backed DP-QPSK as the latter requires significant chip support to perform the digital processing for signal recovery for each channel. Given the PIC’s 10 channels, the power consumption would be prohibitive. Instead Infinera tackles dispersion using a simpler, power-efficient optical design.

Is there a performance hit using DP-DQPSK? “There is a nominal industry figure, 1,600km reach being a good number,” says Welch. “For ultra long haul, we absolutely meet that.”

Infinera has still to launch the 400Gbps PIC whereas transponder-based system vendors have been shipping systems delivering 40Gbps lightpaths for several years. But the company says that the PIC exists, is working and all that is left is “managing it onto the manufacturing line”.

“The 40/100G area is shaping up to be the equivalent of breaking the sound barrier,” says Brad Smith, senior vice president at optical transceiver market research firm LightCounting. He questions the likely progress of optical component assemblies given they have far too many technical, cost, and size limitations. “PICs and silicon photonics have a shot at changing the game,” he says. “But the capital investment is very high with relatively low associated volumes.”

PON: an integration battleground

PON is one market where both hybrid and monolithic integration are competing with discrete-based optical transceiver designs. “Here the whole issue is cost – it’s not performance,” says Liu.

When Finisar entered the GPON transceiver market two years ago it conducted as survey as to what was available. What it found was revealing. “No-one was using the newer technologies, it was all the traditional technique based on TO cans,” said Julie Eng, vice president of optical engineering at Finisar. Mounted within the TO cans are active components such as a distributed-feedback (DFB) or Fabry-Perot laser, or a photo-detector. This is what integrated optics - whether a hybrid design basedon PLC or an indium phosphide monolithic PIC - is looking to displace.

“There is a huge infrastructure – millions of TO cans - and the challenge for hybrid and monolithic integration is that they are chasing a cost-curve that continues to come down,” says Eng.

According to NeoPhotonics’ Lipscomb, it is also hard for monolithic or hybrid integration to match the specifications of TO cans. “FTTx is similar to ROADMs, once one technology is established it is difficult for another to displace it,” he says.

But this is exactly what Canadian firms Enablence Technologies and OneChip Photonics are aiming to do.

Enablence, a hybrid integration specialist, uses a PLC-based design for PON. Onto the PLC are coupled a laser and detector for a diplexer PON design, or for a triplexer - two detectors. A common PLC optical platform is used for the different standards – Broadband PON, Ethernet PON (EPON) and Gigabit PON (GPON) - boosting unit volumes. All that is changed are the actives, for example a Fabry-Perot laser is added to the platform for 10km-reach EPON or a DFB for 20km GPON transceivers. Wavelength filtering is also performed using the PLC waveguides.

“Competing with TO cans in PON is challenging,” admits Matt Pearson, vice president of engineering at Enablence. That’s because the discrete design’s assembly is highly manual, benefiting from Far Eastern labour rates.

A hybrid approach brings several benefits, says Pearson: packaging a highly-integrated device is simpler compared to the numerous piece parts using TO cans. “It is also possible to seal at the chip level not at the module level, such that non-hermetic package can be used,” says Pearson.

There is also an additional, albeit indirect, benefit. Using hybrid integration, Enablence can reuse its intellectual property. “The same wafer process used for PON can be used for 40 and 100 Gig applications,” says Pearson. “These promise better margins as they are higher-end products.”

Enablence claims hybrid also scores when compared to monolithic integration. A hybrid design doesn’t sacrifice system performance: optimised lasers and detectors are used to meet the design specification. In contrast, performance compromises are inevitable for each of the optical functions – lasers, detectors, filtering - given that all are made in a single manufacturing process.

OneChip's EPON diplexer PIC seated on a silicon optical bench and showing the connecting fibreOneChip counters by noting the cost benefits of monolithic integration: its EPON-based transceivers are claimed to be 25 percent cheaper than competing designs. “It is not just integration [and the compact design] but there is a completely different automated packaging of the transceiver,” says Andy Weirich, OneChip’s vice president of product line management.

OneChip's EPON diplexer PIC seated on a silicon optical bench and showing the connecting fibreOneChip counters by noting the cost benefits of monolithic integration: its EPON-based transceivers are claimed to be 25 percent cheaper than competing designs. “It is not just integration [and the compact design] but there is a completely different automated packaging of the transceiver,” says Andy Weirich, OneChip’s vice president of product line management.

The company also argues that all three approaches each have their particular compromises, and that all its optical functions are high performance: the company uses a DFB laser and an optically pre-amplified photo-detector for its designs. “If you can get the best specification with no additional cost, what advantage is there of buying a cheaper laser?” says Weirich.

“Inelegant as it is, the TO can’s performance is quite good as is its cost,” says Ovum’s Liu. What is evident here is how each company is coming from a different direction, she says: “Enablence points out that a discrete design is not a platform with a future whereas the likes of Finisar are saying: do we care?”

That said, Finisar’s Eng does expect photonic integration to be increasingly used for PON: “Its time will come, we are just not at that time now.”

Photonic integration will also be used in emerging standards such as wavelength division multiplexing PON (WDM-PON), especially at the head-end where the optical line terminal (OLT) resides.

“WDM-PON is very much point-to-point even though the fibre is shared like a normal PON,” says David Smith, CTO at CIP Technologies. “When you get in the central office there is a mass of equipment just like point-to-point [access].” The opportunity is to integrate the OLT’s lasers – typically 32 or 64 - into arrays, which will also save power, says Smith.

Tunables and interconnects

Other market segments are benefiting from photonic integration besides 40 and 100Gbps transmission and PON.

JDS Uniphase’s XFP module-based tunable laser is possible by monolithically integration the laser and Mach-Zehnder modulator. Not only is the resulting tunable laser compact – it is a few millimeters long - such that it and the associated electronics fit within the module, but the power consumption is below the pluggable’s 3.5W ceiling.

JDS Uniphase has also developed a compact optical amplifier that extends long-haul optical transmission before electrical signal regeneration is needed. A PLC chip is used to replace some 50 discrete optical components including isolators, photo-detectors for signal monitoring, a variable pump splitter and tunable gain-flattening and tilt filters.

The result is an amplifier halved in size and simpler to make since the PLC removes the need to route and splice fibres linking the discretes. Moreover, JDS Uniphase can use different PLC manufacturing masks to enable specific functions for particular customers. This is the closest the optical world gets to a programmable IC.

Towards 1 terabit-per-second interfaces: a hybrid integrated prototype as part of an NIST project involving CyOptics and Kotura. Click on the photo for more details

Towards 1 terabit-per-second interfaces: a hybrid integrated prototype as part of an NIST project involving CyOptics and Kotura. Click on the photo for more details

The emerging 40 and 100 Gigabit Ethernet interface standards are another area suited for future integration. “What is driving optical integration here is size,” says Eng. “How do you fit 100Gigabit in a 3x5 inch module? That is cutting the size in half and will require a lot of R&D effort.”

In particular, optical integration will be needed to implement the 40GBASE-LR4 Gigabit Ethernet standard within a QSFP module. “You can’t fit four TO can lasers and four TO can receivers into a QSFP module,” says Rochus.

It is the 40 and 100 Gigabit Ethernet market that is the higher end market that also interests Enablence. “The drivers for PON and 100 Gigabit may be different but it’s the same PLC technology,” says Pearson. A PON diplexer may integrate one laser and one detector, for 100G it’s ten lasers and ten detectors, he says.

What next?

“Bandwidth growth is forcing us to consider architectures not considered before,” says Alcatel Lucent’s Bucci. The system vendor is accelerating its integration activities, whether it is integrating two wavelength-selective switches in a package or developing ‘electro-optic engines’ that combine advanced modulation optics and digital signal processing.

Moreover, operators themselves are more open to networking change due to the tremendous challenges they face, says Bucci: “They are being freed to do more, to take more risks.”

Welch believes one significant development that PICs will enable – perhaps a couple of years out - is adding and dropping at the packet level, at every site in the core network. “This will enable lots of reconfigurability and much finer granularity, delivering another level of networking efficiency,” he says.

Is this leading to disruption - the equivalent of digital cameras on handsets? Time will tell.

Click here for a mindmap of this article in PDF form.