Nokia jumps a class with its PSE-6s coherent modem

- The 130 gigabaud (GBd) PSE-6s coherent modem is Nokia’s first in-house design for high-end optical transport systems

- The PSE-6s can send an 800 gigabit Ethernet (800GbE) payload over 2,000km and 1.2 terabits of data over 100km.

- Two PSE-6s DSPs can send three 800GbE signals over two 1.2-terabit wavelengths

Nokia has unveiled its latest coherent modem, the super coherent Photonic Service Engine 6s (PSE-6s) that will power its optical transport platforms in the coming years.

The PSE-6s comes three years after Nokia announced its current generation of coherent digital signal processors (DSPs): the PSE-Vs DSP for the long-haul and the compact PSE-Vc for the coherent pluggable market.

Nokia is only detailing the PSE-6s; its next-generation coherent modem for pluggables will be a future announcement.

Nokia will demonstrate the PSE-6s at the upcoming OFC show in March while field trials involving systems using the PSE-6s will start in the year’s second half.

Reducing cost per bit

In 2020, Nokia bought Elenion, a silicon photonics company specialising in coherent optics.

The PSE-6s is Nokia’s first in-house coherent modem – the coherent DSP and associated optics – targeting the most demanding optical transport applications.

Nokia points out that coherent systems started approaching the Shannon limit two generations ago.

In the past, operators could reduce the cost of optical transport by sending more data down a fibre; upgrading the optical signal from 100 to 200 to 400 gigabit required only a 50GHz channel.

“You were getting more fibre capacity with each generation,” says Serge Melle, director of product marketing, optical networks at Nokia. And this helped the continual reduction of the cost-per-bit metric.

But with more advanced DSPs, implemented using 16nm, 7nm, and now 5nm CMOS, going to a higher symbol rate and hence data rate requires more spectrum, says Melle.

Increasing the symbol rate is still beneficial. It allows more data to be sent using the same modulation scheme or transmitting the same data payload over longer distances.

“So one of the things we are looking to do with the PSE-6s is how do we still enable a lower total cost of ownership even though you don’t get more capacity per wavelength or fibre,” says Melle.

Symbol rate classes

Coherent optics from the leading vendors use a symbol rate of 90-107 gigabaud (GBd), while Cisco-owned Acacia’s latest 1.2-terabit coherent modem in a CIM-8 module operates at 140GBd.

Acacia uses a classification system based on symbol rate. First-generation coherent systems operating at 30-34GBd are deemed Class 1. Class 2 doubles the baud rates to 60-68GBd, the symbol rate window used for 400ZR coherent optics, for hyperscalers to connect equipment across their data centres up to 120km apart.

The DSPs from the leading optical transport systems vendors operating at 90-107GBd are an intermediate step between Class 2 and Class 3 using Acacia’s classification. In contrast, Acacia has jumped directly from Class 2 to Class 3 with its 140GBd CIM-8 coherent modem.

Competitors view Acacia’s classification scheme as a marketing exercise and counter that their 90-107GBd optical transport systems benefited customers for over two years.

Nokia’s 90GBd PSE-Vs can send 400 gigabits using quadrature phase-shift keying (QPSK) over 3,000km. This contrasts with its earlier 67GBd PSE-3s that sends 400GbE up to 1,000km using 16-QAM.

However, with the PSE-Vs, Nokia, unlike its optical transport competitors, Infinera, Ciena and Huawei, decided not to support 800-gigabit wavelengths.

Nokia argued that 7nm CMOS, 90-100GBd coherent optics tops out at 600 gigabit when used for distances of several hundred kilometers, while metro-regional distances are more economically served using 400-gigabit pluggable optics such as the CFP2 implementing 400ZR+.

With the 130Gbd PSE-6s, Nokia has a Class 3 coherent modem with the PSE-6s capable of sending 800 gigabits more than 2,000km.

The PSE-6s also doubles the maximum data rate of the PSE-Vs to 1.2 terabits per wavelength. However, at 1.2 terabits, the reach is 100-plus km, valuable for very high capacity metro transport and data centre interconnect.

Scale, reach and power consumption per bit

Nokia highlights the PSE-6s’ main three performance metric improvements.

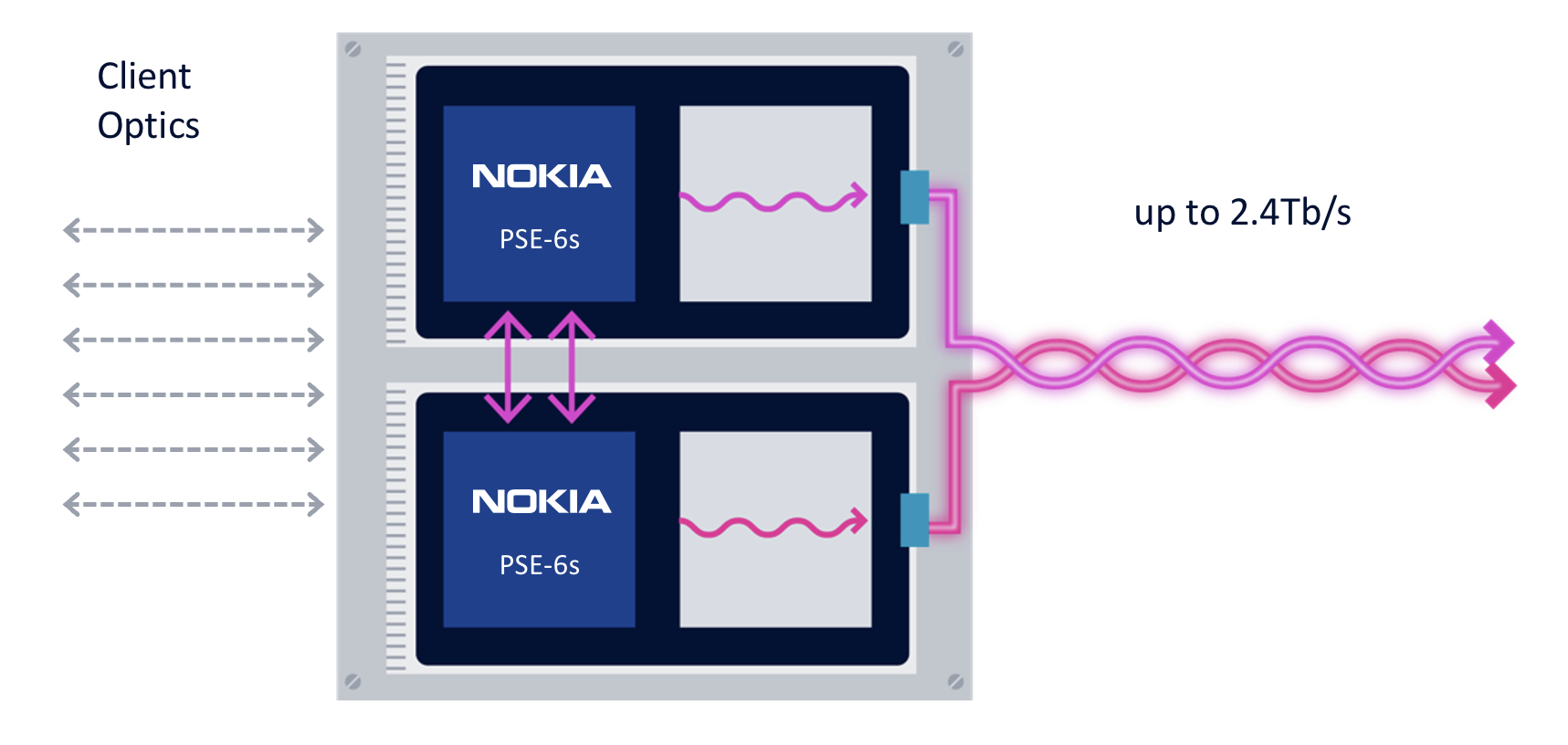

First, the coherent modem delivers scaling: two coherent optical engines fit on a line card to deliver 2.4 terabits to transport emerging high-speed services such as 800GbE.

The two PSE-6s are linked using a dedicated interface to share the client-side signals (see diagram).

“We are not the only ones introducing a 5nm solution, but I think we are the only ones that allow two DSPs to work together,” says Melle.

Without the interface, a single 800GbE and up to four 100GbE clients or a 400GbE client can be sent over each DSP’s 1.2-terabit wavelength. Adding the interface, an operator can send three uniform 800GbE clients, with the interface splitting the third 800GbE client between the two DSPs.

“In a single line card, you can stripe the three 800-gigabit services rather than have to deploy three separate line cards in the network,” says Melle.

Nokia is not detailing the interface used to link the DSPs but said that the interface is used for data only and not to share signal processing resources between the ASICs.

“There is an extra amount of circuitry to share the client bandwidth across the two DSPs, but it is not high power consuming, and most transponders have some circuitry between the clients and the DSP,” says Melle. “So the incremental ‘power tax’ is marginal; it doesn’t add any significant power overhead.”

The resulting 2.4-terabit transmission is sent as two 1.2-terabit wavelengths, each occupying a 150GHz-wide channel. Existing systems that operate at 90-107GBd typically use a 112.5GHz channel for an 800-gigabit transmission, so the PSE-6s delivers a fibre capacity benefit.

The two wavelengths can be bonded, as in a two-channel ‘super-channel’, or sent to separate locations.

The second improvement is optical performance. For example, an 800-gigabit payload can travel over 2,000km. Nokia claims this is 3x the reach of existing commercial optical transport systems.

The improved transmission performance is achieved using a combination of the 130GBd baud rate, probabilistic constellation shaping (PCS), and improved forward error correction (FEC). Melle says the contributions to the improvement are 90 per cent baud rate and 10 per cent due to coherent modem algorithm tweaks.

“Baud rate is king; that is what really drives this improved performance,” says Melle.

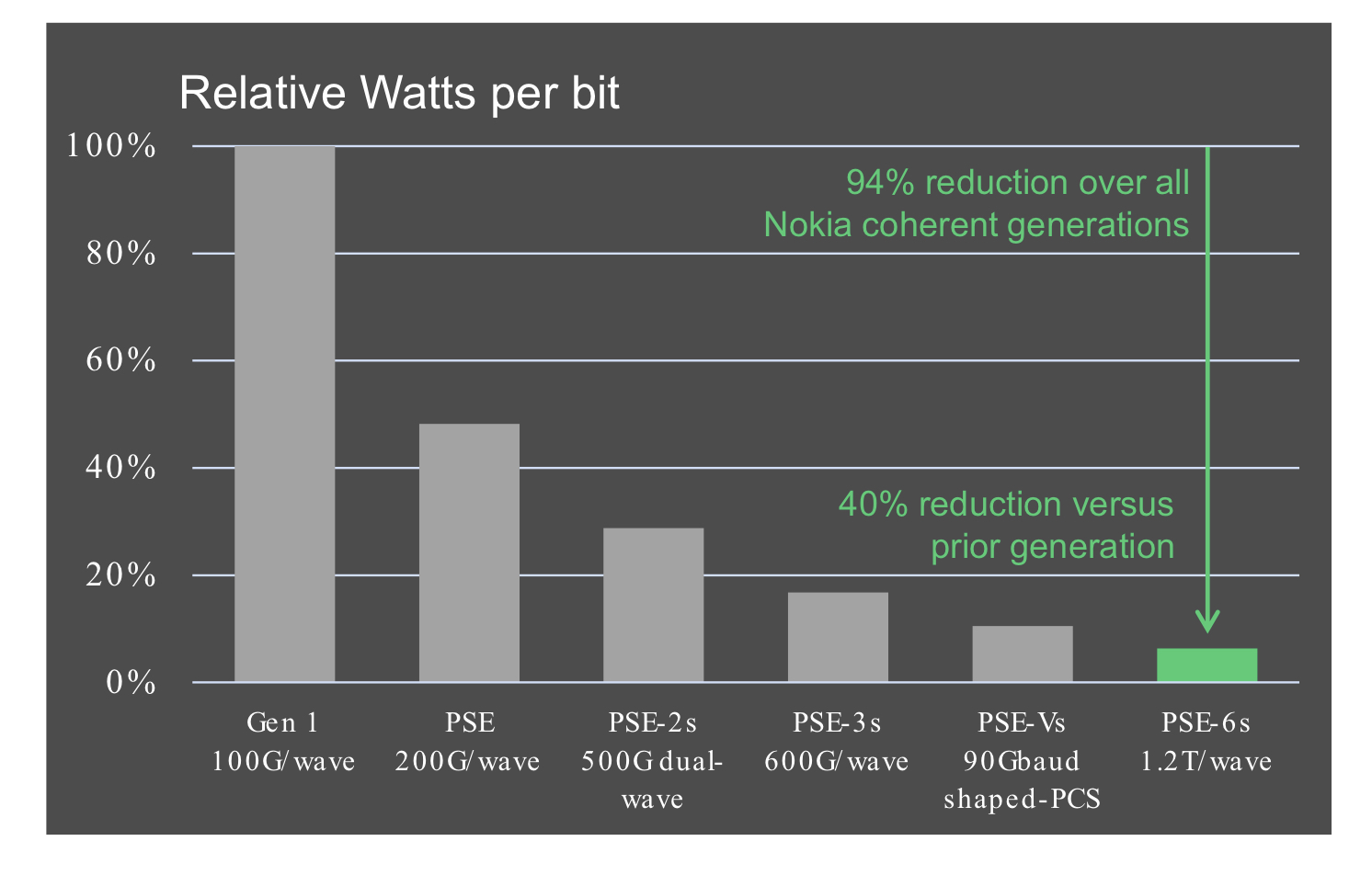

The third benefit is reduced power consumption at the device and system (networking) levels.

Using a 5nm finFET CMOS process to make the PSE-6s DSP ASIC and developing denser line cards (two modems per card) means systems will consume 60 per cent less power than Nokia’s existing coherent technology.

According to Nokia, the PSE-6s optical engine consumes 40 per cent fewer Watts per bit compared to the PSE-Vs.

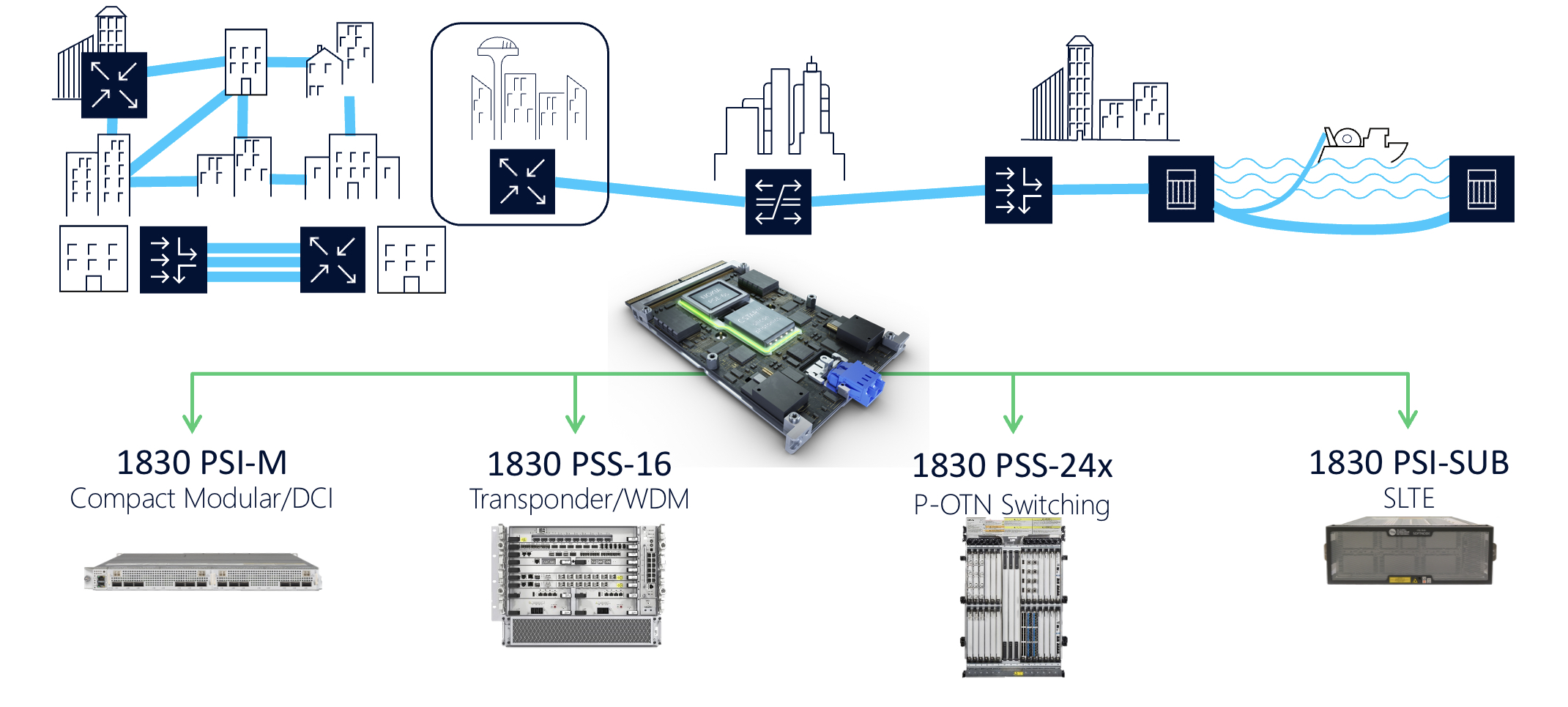

Nokia 1830 transport systems

The PSE-6s line cards fit into Nokia’s existing range of 1830 transport platforms.

These include the 1830 PSI-M compact modular data centre interconnect, the 1830 PSS-16 transponder and WDM line system, the 1830 PSS-24x P-OTN and switching chassis, and the 1830 PSI-SUB subsea line-terminating equipment.

For example, the PSI-M platform can hold two line cards, each with two PSE-6s.

Coherent gets a boost with probabilistic shaping

Nokia has detailed its next-generation PSE-3 digital signal processor (DSP) family for coherent optical transmission.

The PSE-3s is the industry’s first announced coherent DSP that supports probabilistic constellation shaping, claims Nokia.

Probabilistic shaping is the latest in a series of techniques adopted to improve coherent optical transmission performance. These techniques include higher-order modulation, soft-decision forward error correction (SD-FEC), multi-dimensional coding, Nyquist filtering and higher baud rates.

Kyle Hollasch

Kyle Hollasch

“There is an element here that the last big gains have now been had,” says Kyle Hollasch, director of product marketing for optical networks at Nokia.

Probabilistic shaping is a signal-processing technique that squeezes the last bit of capacity out of a fibre’s spectrum, approaching what is known as the non-linear Shannon Limit.

“We are not saying we absolutely hit the Shannon Limit but we are extremely close: tenths of a decibel whereas most modern systems are a couple of decibels away from the theoretical maximum,” says Hollasch.

Satisfying requirements

Optical transport equipment vendors are continually challenged to meet the requirements of the telcos and the webscale players.

One issue is meeting the continual growth in IP traffic: telcos are experiencing 25 percent yearly traffic growth whereas for the webscale players it is 60 percent. Vendors must also ensure that their equipment keeps reducing the cost of transport when measured as the cost-per-bit.

Operators also want to automate their networks. Technologies such as flexible-grid, reconfigurable optical add/drop multiplexers (ROADMs), higher-order modulation and higher baud rates all add flexibility to the optical layer but at the expense of complexity.

There is an element here that the last big gains have now been had

“It is easy to say software-defined networking will hide all that complexity,” says Hollasch. “But hardware has an important role: to keep delivering capacity gains but also make the network simpler.”

Satisfying these demands is what Nokia set out to achieve when designing the PSE-3s.

Capacity and cost

Like the current PSE-2 coherent DSPs that Nokia launched in 2016, two chips make up the PSE-3 family: the super coherent PSE-3s and the low-power compact PSE-3c.

The PSE-3s is a 1.2-terabit chip that can drive two sets of optics, each capable of transmitting 100 to 600 gigabit wavelengths. This compares to the 500-gigabit PSE-2s that can drive two wavelengths, each up to 250Gbps.

The low-power PSE-3c also can transmit more traffic, 100 and 200-gigabit wavelengths, twice the capacity of the 100-gigabit PSE-2c.

Nokia has used a software model of two operators’ networks, one an North America and another in Germany, to assess the PSE-3s.

The PSE-3s’ probabilistic shaping delivers 70% more capacity while using a third fewer line cards when compared with existing commercial systems based on 100Gbps for long haul and 200Gbps for the metro. When the PSE-3s is compared with existing Nokia PSE-2s-based platforms on the same networks, a 25 percent capacity gain is achieved using a quarter fewer line cards.

Hollasch says that the capacity gain is 1.7x and not greater because 100-gigabit coherent technology used for long haul is already spectrally efficient. “But it is less so for shorter distances and you do get more capacity gains in the metro,” says Hollasch.

Probabilistic shaping

The 16nm CMOS PSE-3s supports a symbol rate of up to 67Gbaud. This compares to the 28nm CMOS PSE-2s that uses two symbol rates: 33Gbaud and 45Gbaud.

The PSE-3s’ higher baud rate results in a dense wavelength-division multiplexing (DWDM) channel width of 75GHz. Traditional fixed-grid channels are 50GHz wide. With 75GHz-wide channels, 64 lightpaths can fit within the C-band.

The PSE-3s uses one modulation format only: probabilistic shaping 64-ary quadrature amplitude modulation (PS-64QAM). This compares with the PSE-2s that supports six modulations ranging from binary phase-shift keying (BPSK) for the longest spans to 64-QAM for a 400-gigabit wavelength.

Using probabilistic shaping, one modulation format supports data rates from 200 to 600Gbps. For 100Gbps, the PSE-3s uses a lower baud rate in order to fit existing 50GHz-wide channels.

In current optical networks, all the constellation points of the various modulation formats are used with equal probability. BPSK has two constellation points while 64-QAM has 64. Probabilistic shaping does not give equal weighting to all the constellation points. Instead, it favours those with lower energy, represented by those points closer to the origin in a constellation graph. The only time all the constellation points are used is at the maximum data rate - 600Gbps for the PSE-3s.

Using the inner, lower energy constellation points more frequently than the outer points reduces the overall average energy and this improves the signal-to-noise ratio. That is because the symbol error rate at the receiver is dominated by the distance between neighbouring points on the constellation. Reducing the average energy still keeps the distance between the points the same, but since a constant signal power level is used for DWDM transmission, applying gain increases the distance between the constellation points.

“We separate these points further in space - the Euclidean distance between them,” says Hollasch. “That is where the shaping gain comes from.”

Changing the probabilistic shaping in response to feedback from the chip, from the network, we think that is a powerful innovation

Using probabilistic shaping delivers a maximum 1.53dB of improvement in a linear transmission channel. In practice, Nokia says it achieves 1dB. “One dB does not sound a lot but I call it the ultimate dB, the last dB in addition to all the other techniques,” he says.

By using few and fewer of the constellation points, or favouring those points closer to the origin, reduces the data that can be transported. This is how the data rate is reduced from the maximum 600Gbps to 200Gbps.

To implement probabilistic shaping, Nokia has developed an IP block for the chip called the distribution matcher. The matcher maps the input data stream as rates as high as 1.2 terabits-per-second onto the constellation points in a non-uniform way.

Theoretically, probabilistic shaping allows any chosen data rate to be used. But what dictates the actual data rate gradations is the granularity of the client signals. The Optical Internetworking Forum’s Flex Ethernet (FlexE) standard defines 25-gigabit increments and that will be the size of the line-side data rate increments.

Embracing a single modulation format and a 75GHz channel results in network operation benefits, says Hollasch: “It stops you having to worry and manage a complicated spectrum across a broad network.” And it also offers the prospect of network optimisation. “Changing the probabilistic shaping in response to feedback from the chip, from the network, we think that is a powerful innovation,” says Hollasch.

The reach performance of the PSE-3s using 62Gbaud and PS-64QAM. The reach performance of the PSE-2s is shown (where relevant) for comparison purposes.

The reach performance of the PSE-3s using 62Gbaud and PS-64QAM. The reach performance of the PSE-2s is shown (where relevant) for comparison purposes.

Product plans

The first Nokia product to use the PSE-3 chips is the 1830 Photonic Service Interconnect-Modular, a 1 rack-unit compact modular platform favoured by the webscale players.

Nokia has designed two module-types or ‘sleds’ for the 1830 PSI-M pizza box. The first is a 400-gigabit sled that uses two sets of optics and two PSE-3c chips along with four 100-gigabit client-side interfaces. Four such 400-gigabit sleds fit within the platform to deliver a total of 1.6 terabits of line-side capacity.

In contrast, two double-width sleds fit within the platform using the PSE-3s. Each sled has one PSE-3 chip and two sets of optics, each capable of up to a 600-gigabit wavelength, and a dozen 100-gigabit interfaces. Here the line-side capacity is 2.4 terabits.

Nokia says the 400-gigabit sleds will be available in the first half of this year whereas the 1.2 terabit sleds will start shipping at the year-end or early 2019. The first samples of the PSE-3s are expected in the second half of 2018. Nokia will then migrate the PSE-3s to the rest of its optical transport platform portfolio.

So has coherent largely run its course?

“In terms of a major innovation in signal processing, probabilistic shaping is completing the coherent picture,” says Hollasch. There will be future coherent DSP chips based on more advanced process nodes than 16nm with symbol rates approaching 100GBaud. Higher data rates per wavelength will result but at the expense of a wider channel width. But once probabilistic shaping is deployed, further spectral efficiencies will be limited.