Access drives a need for 10G compact aggregation boxes

Infinera has unveiled a platform to aggregate multiple 10-gigabit traffic streams originating in the access network.

The 1.6-terabit HDEA 1600G platform is designed to aggregate 80, 10-gigabit wavelengths. The use of ten-gigabit wavelengths in access continues to grow with the advent of 5G mobile backhaul and developments in cable and passive optical networking (PON).

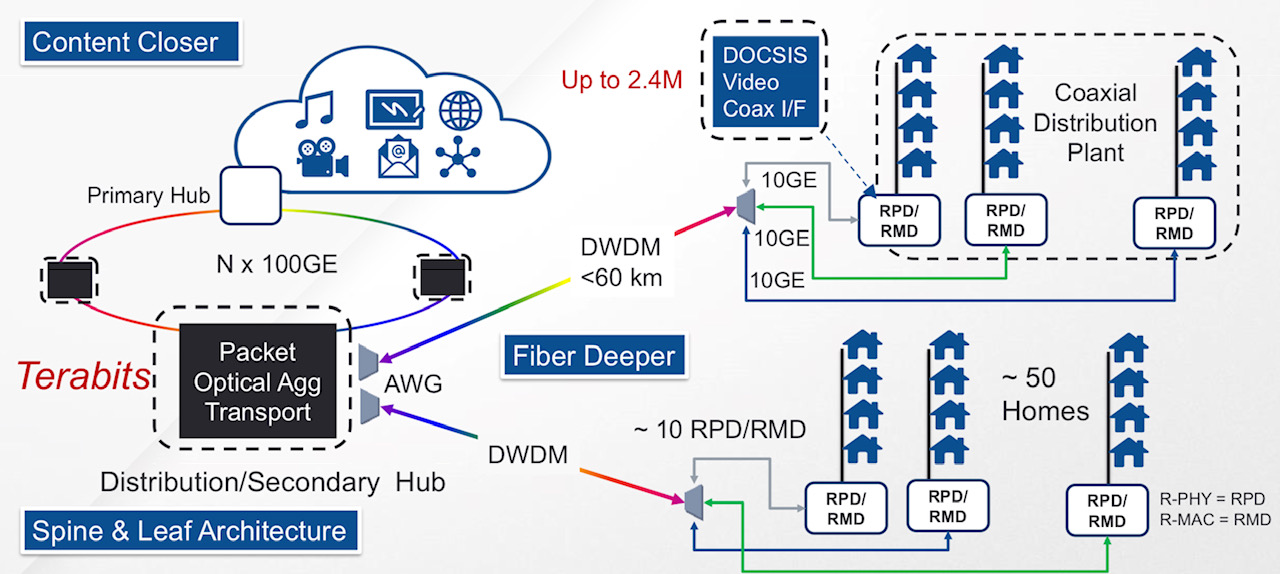

A distributed access architecture being embraced by cable operators. Shown are the remote PHY devices (RPD) or remote MAC-PHY devices (RMD), functionality moved out of the secondary hub and closer to the end user. Also shown is how DWDM technology is moved closer to the edge of the network. Source: Infinera.

A distributed access architecture being embraced by cable operators. Shown are the remote PHY devices (RPD) or remote MAC-PHY devices (RMD), functionality moved out of the secondary hub and closer to the end user. Also shown is how DWDM technology is moved closer to the edge of the network. Source: Infinera.

Infinera has adopted a novel mechanical design for its 1 rack unit (1RU) HDEA 1600G that uses the sides of the platform to fit 80 SFP+ optical modules.

The platform also features a 1.6-terabit Ethernet switch chip that aggregates the traffic from the 10-gigabit streams to fill 100-gigabit wavelengths that are passed to other switching or transport platforms for transmission into the network.

Distributed access architecture

Jon Baldry, metro marketing director at Infinera, cites the adoption of a distributed access architecture (DAA) by cable operators as an example of 10-gigabit links that are set to proliferate in the access network.

DAA is being adopted by cable operators to compete with the telecom operators’ rollout of fibre-to-the-home (FTTH) broadband access technology.

A recent report by market research firm, Ovum, addressing DAA in the North American market, discusses how the architectural approach will free up space in cable headends, reduce the operators’ operational costs, and allow the delivery of greater bandwidth to subscribers.

Implementing DAA involves bringing fibre as well as cable network functionality closer to the user. Such functionality includes remote PHY devices and remote MAC-PHY devices. It is these devices that will use a 10-gigabit interface, says Baldry: “The traffic they will be running at first will be two or three gigabits over that 10-gigabit link.”

Julie Kunstler, principal analyst at Ovum’s Network Infrastructure and Software group, says the choice whether to deploy a remote PHY or a remote MAC-PHY architecture is a issue of an operator's ‘religion’. What is important, she says, is that both options exploit the existing hybrid fibre coax (HFC) architecture to boost the speed tiers delivered to users.

The current, pre-DAA, cable network architecture. Source: Infinera.

In the current pre-DAA architecture, the cable network comprises cable headends and secondary distribution hubs (see diagram above). It is at the secondary hub that the dense wavelength-division multiplexing (DWDM) network terminates. From there, RF over fibre is carried over the hybrid fibre-coax (HFC) plant. The HFC plant also requires amplifier chains to overcome cable attenuation and the losses resulting from the cable splits that deliver the RF signals to the homes.

Typically, an HFC node in the cable network serves up to 500 homes. With the adoption of DAA and the use of remote PHYs, the amplifier chains can be removed with each PHY serving 50 homes (see diagram top).

“Basically DWDM is being pushed out to the remote PHY devices,” says Baldry. The remote PHYs can be as far as 60km from the secondary hub.

“DAA is a classic example where you will have dense 10-gigabit links all coming together at one location,” says Baldry. “Worst case, you can have 600-700 remote PHY devices terminating at a secondary hub.”

The same applies to cellular.

At present 4G networks use 1-gigabit links for mobile backhaul but 5G will use 10-gigabit and 25-gigabit links in a year or two. “So the edge of the WDM network has really jumped from 1 gigabit to 10 gigabit,” says Baldry.

It is the aggregation of large numbers of 10-gigabit links that the HDEA 1600G platform is designed to address.

HDEA 1600G

Only a certain number of pluggable interfaces can fit on the front panel of a 1RH box. To accommodate 80, 10-gigabit streams, the two sides of the platform are used for the interfaces. Using the HDEA’s sides creates much more space for the 1RU’s input-output (I/O) compared to traditional transport kit, says Baldry.

The 40 SFP+ modules on each side of the platform are accessed by pulling the shelf out and this can be done while it is operational (see photo below). Such an approach is used for supercomputing but Baldry believes Infinera is the first to adopt it for a transport product.

Infinera has also adopted MPO connectors to simplify the fibre management involved in connected 80 SFP+, each module requiring a fibre pair.

The HDEA 1600 has two groups of four MPO connectors on the front panel. Each MPO cluster connects 40 modules on each side, with each MPO cable having 20 fibres to connect 10 SFP+ modules.

A site terminating 400 remote PHYs, for example, requires the connection of 40 MPO cables instead of 800 individual fibres, says Baldry, simplifying installation greatly.

>

“DAA is a classic example where you will have dense 10-gigabit links all coming together at one location. Worst case, you can have 600-700 remote PHY devices terminating at a secondary hub.”

The other end of the MPO cable connects to a dense multiplexer-demultiplexer (mux-demux) unit that separates the individual 10-gigabit access wavelengths received over the DWDM link.

Each mux-demux unit uses an arrayed waveguide grating (AWG) that is tailored to the cable operators’ wavelengths needs. The 24-channel mux-demux design supports 20, 100GHz-wide channels for the 10-gigabit wavelengths and four wavelengths reserved for business services. Business services have become an important part of the cable operators’ revenues.

Infinera says the HDEA platform supports the extended C-band for a total of 96 wavelengths.

The company says it will develop different AWG configurations tailored for the wavelengths and channel count required for the different access applications.

In the rack, the HDEA aggregation platform takes up one shelf, while eight mux-demux units take up another 1RU. Space is left in between to house the cabling between the two.

The HDEA 1600G pulled out of the rack, showing the MPO connectors and the space to house the cabling between the HDEA and the rack of compact AWGs. Source: Infinera.

Baldry points out that the four business service wavelengths are not touched by the HDEA platform, Rather, these are routed to separate Ethernet switches dedicated to business customers. "We break those wavelengths out and hand them over to whatever system the operator is using," he says.

The HDEA 1600G also features eight 100-gigabit line-side interfaces that carry the aggregated cable access streams. Infinera is not revealing the supplier of the 1.6 terabit switch silicon - 800-gigabit for client-side capacity and 800-gigabit for line-side capacity - it is using for the HDEA platform.

The platform supports all the software Infinera uses for its EMXP, a packet-optical switch tailored for access and aggregation that is part of Infinera’s XTM family of products. Features include multi-chassis link aggregation group (MC-LAG), ring protection, all the Metro Ethernet Forum services, and synchronisation for mobile networks, says Baldry

Auto-Lambda

Infinera has developed what it calls its Auto-Lambda technology to simplify the wavelength management of the remote PHY devices.

Here, the optics set up the connection instead of a field engineer using a spreadsheet to determine which wavelength to use for a particular remote PHY. Tunable SFP+ modules can be used at the remote PHY devices only with fixed-wavelength (grey) SFP+ modules used by the HDEA platform to save on costs, or both ends can use tunable optics. Using tunable SFP+ modules at each end may be more expensive but the operator gains flexibility and sparing benefits.

Jon Baldry

Establishing a link when using fixed optics within the HDEA platform, the SFP+ is operated in a listening mode only. When a tunable SFP+ transceiver is plugged in at a remote PHY, which could be days later, it cycles through each wavelength. The blocking nature of the AWG means that such cycling does not disturb other wavelengths already in use.

Once the tunable SFP+ reaches the required wavelength, the transmitted signal is passed through the AWG to reach the listening transceiver at the switch. On receipt of the signal, the switch SFP+ turns on its transmitter and talks to the remote transceiver to establish the link.

For the four business wavelengths, both ends of the link use auto-tunable SFP+ modules, what is referred to a duel-ended solution. That is because both end-point systems may not be Infinera platforms and may have no knowledge as to how to manage WDM wavelengths, says Baldry.

In this more complex scenario, the time taken to establish a link is theoretically much longer. The remote end module has to cycle through all the wavelengths and if no connection is made, the near end transceiver changes its transmit wavelength and the remote end’s wavelength cycling is repeated.

Given that a sweep can take two minutes or more, an 80-wavelength system could take close to three hours in the worst case to establish the link; an unacceptable delay.

Infinera is not detailing how its duel-ended scheme works but a combination of scanning and communications is used between the two ends. Infinera had shown such a duel-ended scheme set up a link in 4 minutes and believes it can halve that time.

Finisar detailed its own Flextune fast-tuning technology at ECOC 2018. However, Infinera stresses its technology is different.

Infinera says it is talking to several pluggable optical module makers. “They are working on 25-gigabit optics which we are going to need for 5G,” says Baldry. “As soon as they come along, with the same firmware, we then have auto-tunable for 5G.”

System benefits

Infinera says its HDEA design delivers several benefits. Using the sides of the box means that the platform supports 80 SFP+ interfaces, twice the capacity of competing designs. In turn, using MPO connectors simplifies the fibre management, benefiting operational costs.

Infinera also believes that the platform’s overall power consumption has a competitive edge. Baldry says Infinera incorporates only the features and hardware needed. “We have deliberately not done a lot of stuff in Layer 2 to get better transport performance,” he says. The result is a more power-efficient and lower latency design. The lower latency is achieved using ‘thin buffers’ as part of the switch’s output-buffered queueing architecture, he says.

The platform supports open application programming interfaces (APIs) such that cable operators can make use of such open framework developments as the Cloud-Optimised Remote Datacentre (CORD) initiative being developed by the Open Networking Foundation. CORD uses open-source software-defined networking (SDN) technology such as ONOS and the OpenFlow protocol to control the box.

An operator can also choose to use Infinera’s Digital Network Administrator (DNA) management software, SDN controller, and orchestration software that it has gained following the Coriant acquisition.

The HDEA 1600G is generally available and in the hands of several customers.

Sckipio improves G.fast’s speed, reach and density

Sckipio has enhanced the performance of its G.fast chipset, demonstrating 1 gigabit data rates over 300 meter of telephone wire. The G.fast broadband standard has been specified for 100 meters only. The Israeli start-up has also demonstrated 2 gigabit performance by bonding two telephone wires.

Michael Weissman

Michael Weissman

“Understand that G.fast is still immature,” says Michael Weissman, co-founder and vice president of marketing at Sckipio. “We have improved the performance of G.fast by 40 percent this summer because we haven’t had time to do the optimisation until now.”

The company also announced a 32-port distribution point unit (DPU), the aggregation unit that is fed via fibre and delivers G.fast to residences.

G.fast is part of the toolbox enabling faster and faster speeds, and fills an important role in the wireline broadband market

The 32-port design is double Sckipio’s current largest DPU design. The DPU uses eight Sckipio 4-port DP3000 distribution port chipsets, and moving to 32 lines requires more demanding processing to tackle the greater crosstalk. Vectoring uses signal processing to implement noise cancellation techniques to counter the crosstalk and is already used for VDSL2.

G.fast

“G.fast is part of the toolbox enabling faster and faster speeds, and fills an important role in the wireline broadband market,” says Julie Kunstler, principal analyst, components at market research firm, Ovum.

G.fast achieves gigabit rates over copper by expanding the usable spectrum to 106 MHz. VDSL2, the current most advanced digital subscriber line (DSL) standard, uses 17 MHz of spectrum. But operating at higher frequencies induces signal attenuation, shortening the reach. VDSL2 is deployed over 1,500 meter links typically whereas G.fast distances will likely be 300 meters or less.

Another issue is signal leakage or crosstalk between copper pairs in a cable bundle that can house tens or hundreds of copper twisted pairs. Moreover, the crosstalk becomes greater with frequency. The leakage causes each twisted pair not only to carry the signal sent but also noise, the sum of the leakage components from neighbouring pairs. Vectoring is used to restore a line's data capacity.

G.fast can be seen as the follow-on to VDSL2 but there are notable differences. Besides the wider 106 MHz spectrum, G.fast uses a different duplexing scheme. DSL uses frequency-division duplexing (FDD) where the data transmission is continuous - upstream (from the home) and downstream - but on different frequency bands or tones. In contrast, G.fast uses time-division duplexing (TDD) where all the spectrum is used to either send data or receive data.

Using TDD, the ability to adapt the upstream and downstream data ratio as well as put G.fast in a low-power mode when idle are features that DSL does not share.

“There are many attributes [of DSL] that are brought into this standard but, at a technical level, G.fast is quite fundamentally different,” says Weissman.

One Tier-1 operator has already done the bake-off and will very soon select its vendors

Status

Sckipio says all the largest operators are testing G.fast in their labs or are conducting field trials but few are going public.

Ovum stresses that telcos are pursuing a variety of broadband strategies with G.fast being just one.

Some operators have decided to deploy fibre, while others are deploying a variety of upgrade technologies - fibre-based and copper-based. G.fast can be a good fit for certain residential neighbourhood topologies, says Kunstler.

The economics of passive optical networking (PON) continues to improve. “The costs of building an optical distribution network has declined significantly, and the costs of PON equipment are reasonable,” says Kunstler, adding that skilled fibre technicians now exist in many countries and working with fibre is easier than ever before.

“Many operators see fibre as important for business services so why not just pull the fibre to support volume-residential and high average-revenue-per-user (ARPU) based business services,” she says. But in some regions, G.fast broadband speeds will be sufficient from a competitive perspective.

“One Tier-1 operator has already done the bake-off and will very soon select its vendors,” says Weissman. “Then the hard work of integrating this into their IT systems starts.”

And BT has announced that it had delivered up to 330 megabit-per-second in a trial of G.fast involving 2,000 homes, and has since announced other trials.

“BT has publically announced it can achieve 500 megabits - up and down - over 300 meters running from their cabinets,” says Weissman. “If BT moves its fibre closer to the distribution point, it will likely achieve 800 or 900 megabit rates.” Accordingly, the average customer could benefit from 500 megabit broadband from as early as 2016. And such broadband performance would be adequate for users for 8 to 10 years, he says

Meanwhile, Sckipio and other G.fast chip vendors, as well as equipment makers are working to ensure that their systems interoperate.

Sckipio has also shown G.fast running over coax cable within multi-dwelling units delivering speeds beyond 1 gigabit. “This allows telcos to compete with cable operators and go in places they have not historically gone,” says Weissman.

Standards work

The ITU-T is working to enhance the G.fast standard further using several techniques.

One is to increase the transmission power which promises to substantially improve performance. Another is to use more advanced modulation to carry extra bits per tone across the wire’s spectrum. The third approach is to double the wire's used spectrum from 106 MHz to 212 MHz.

All three approaches complicate transmission, however. Increasing the signal power and spectrum will increase crosstalk and require more vectoring, while more complex modulation will require advanced signal recovery, as will using more spectrum.

“The guys working in committee need to find the apex of these compromises,” says Weissman, adding that Sckipio believes it can generate a 50 to 70 percent improvement in data rate over a single pair using these enhancements. The standard work is likely be completed next spring.

Sckipio says it has over 30 customers for its chips that are designing over 50 G.fast systems, for the home and/ or the distribution point.

So far Sckipio has announced it is working with Calix, Adtran, Chinese original design manufacturer Cambridge Industries Group (CIG) and Zyxel, and says Sckipio products are on show in over 12 booths at the Broadband World Forum show.

China and the global PON market

China has become the world's biggest market for passive optical network (PON) technology even though deployments there have barely begun. That is because China, with approximately a quarter of a billion households, dwarfs all other markets. Yet according to market research firm Ovum, only 7% of Chinese homes were connected by year end 2011.

"In 2012, BOSAs [board-based PON optical sub-assemblies] will represent the majority versus optical transceivers for PON ONTs and ONUs"

Julie Kunstler, Ovum

Until recently Japan and South Korea were the dominant markets. And while PON deployments continue in these two markets, the rate of deployments has slowed as these optical access markets mature.

According to Ovum, slightly more than 4 million PON optical line terminals (OLTs) ports, located in the central office, were shipped in Asia Pacific in 2011, of which China accounted for the majority. Worldwide OLT shipments for the same period totaled close to 4.5 million. The fact that in China the ratio of OLT to optical network terminal (ONT), the end terminal at the home or building, deployed is relatively low highlights that in the Chinese market the significant growth in PON end terminals is still to come.

The strength of the Chinese market has helped local system vendors Huawei, ZTE and Fiberhome become leading global PON players, accounting for over 85% of the OLTs sold globally in 2011, says Julie Kunstler, principal analayst, optical components at Ovum. Moreover, around 60% of fibre-to-the-x deployments in Europe, Middle East and Africa were supplied by the Chinese vendors. The strongest non-Chinese vendor is Alcatel-Lucent.

Ovum says that the State Grid China Corporation, the largest electric utility company in China, has begun to deploy EPON for their smart grid trial deployments. PON is preferred to wireless technology because of its perceived ability to secure the data. This raises the prospect of two separate PON lines going to each home. But it remains to be seen, says Kunstler, whether this happens or whether the telcos and utilities share the access network.

"After China the next region that will have meaningful numbers is Eastern Europe, followed by South and Central America and we have already seen it in places like Russia,” says Kunstler. Indeed FTTx deployments in Eastern Europe already exceed those in Western Europe.

EPON and GPON

In China both Ethernet PON (EPON) and Gigabit PON (GPON) are being deployed. Ovum estimates that in 2011, 65% of equipment shipments were EPON while GPON represented 35% GPON in China.

China Telecom was the first of the large operators in China to deploy PON and began with EPON. Ovum is now seeing deployments of GPON and in the 3rd quarter of 2012, GPON OLT deployments have overtaken EPON.

China Mobile, not a landline operator, started deployments later and chose GPON. But these GPON deployments are on top of EPON, says Kunstler: "EPON is still heavily deployed by China Telecom, while China Mobile is doing GPON but it is a much smaller player." Moreover, Chinese PON vendors also supplying OLTs that support EPON and GPON, allowing local decisions to be made as to which PON technology is used.

One trend that is impacting the traditional PON optical transceiver market is the growing use of board-based PON optical sub-assemblies (BOSAs). Such PON optics dispenses with the traditional traditional optical module form factor in the interest of trimming costs.

“A number of the larger, established ODMs [original design manufacturers] have begun to ship BOSA-based PON CPEs,” says Kunstler. In 2012, BOSAs will represent the majority versus optical transceivers for PON ONTs/ONUs.” says Kunstler.

10 Gigabit PON

Ovum says that there has been very few deployments of next generation 10G EPON and XG-PON, the 10 Gigabit version of GPON.

"There have been small amounts of 10G [EPON] in China," says Kunstler. "We are talking hundreds or thousands, not the tens of thousands [of units]."

One reason for this is the relative high cost of 10 Gigabit PON which is still in its infancy. Another is the growing shift to deploy fibre-to-the-home (FTTh) versus fibre-to-the-building deployments in China. 10 Gigabit PON makes more sense in multi-dwelling units where the incoming signal is split between apartments. Moving to 10G EPON boosts the incoming bandwidth by 10x while XG-PON would increase the bandwidth by 4x. "The need for 10 Gig for multi-dwelling units is not as strong as originally thought," says Kunstler.

It is a chicken-and-egg issue with 10G PON, says Kunstler. The price of 10G optics would go down if there was more demand, and if there was more demand, the optical vendors would work on bringing down cost. "10G GPON will happen but will take longer," says Kunstler, with volumes starting to ramp from 2014.

However, Ovum thinks that a stronger market application for 10G PON will be for supporting wireless backhaul. The market research company is seeing early deployments of PON for wireless backhaul especially for small cell sites (e.g. picocells). Small cells are typically deployed in urban areas which is where FTTx is deployed. It is too early to know the market forecast for this application but PON will join the list of communications technologies supporting wireless backhaul.

Challenges

Despite the huge expected growth in deployments, driven by China, challenges remain for PON optical transceiver and chip vendors.

The margins on optics and PON silicon continue to be squeezed. ODMs using BOSAs are putting pricing pressure on PON transceiver costs while the vertical integration strategy of system vendors such as Huawei, which also develops some of its own components squeezes, out various independent players. Huawei has its own silicon arm called HiSilicon and its activities in PON has impacted the chip opportunity of the PON merchant suppliers.

"Depending upon who the customer is, depending upon the pricing, depending on the features and the functions, Huawei will make the decision whether they are using HiSilicon or whether they are using merchant silicon from an independent vendor, for example," says Kunstler.

There has been consolidation in the PON chip space as well as several new players. For example, Broadcom acquired Teknouvs and Broadlight while Atheros acquired Opulan and Atheros was then acquired by Qualcomm. Marvell acquired a very small start-up and is now competing with Atheros and Broadcom. Most recently, Realtek is rumored to have a very low-cost PON chip.