OFC 2014 industry reflections - Part 1

T.J. Xia, distinguished member of technical staff at Verizon

The CFP2 form factor pluggable - analogue coherent optics (CFP2-ACO) at 100 and 200 Gig will become the main choice for metro core networks in the near future.

I learnt that the discrete multitone (DMT) modulation format seems the right choice for a low-cost, single-wavelength direct-detection 100 Gigabit Ethernet (GbE) interface for data ports, and a 4xDMT for 400GbE ports.

As for developments to watch, photonic switches will play a much more important role for intra-data centre connections. As the port capacity of top-of-rack switches gets larger, photonic switches have more cost advantages over middle stage electrical switches.

Don McCullough, Ericsson's director of strategic communications at group function technology

The biggest trend in networking right now is software-defined networking (SDN) and Network Function Virtualisation (NFV), and both were on display at OFC. We see that the combination of SDN and NFV in the control and software domains will directly impact optical networks. The Ericsson-Ciena partnership embodies this trend with its agreement to develop joint transport solutions for IP-optical convergence and service provider SDN.

We learnt that network transformation, both at the control layer (SDN and NFV) and at the data plane layer, including optical, is happening at the network operators. Related to that, we also saw interest at OFC in the announcement that AT&T made at Mobile World Congress about their User-Defined Network Cloud and Domain 2.0 strategy where AT&T has selected to work with Ericsson on integration and transformation services.

We learnt that network transformation, both at the control layer (SDN and NFV) and at the data plane layer, including optical, is happening at the network operators. Related to that, we also saw interest at OFC in the announcement that AT&T made at Mobile World Congress about their User-Defined Network Cloud and Domain 2.0 strategy where AT&T has selected to work with Ericsson on integration and transformation services.

We will continue to watch the on-going deployment of SDN and NFV to control wide area networks including optical. We expect more joint developments agreements to connect SDN and NFV with optical networking, like the Ericsson-Ciena one.

One new thing for 2014 is that we expect to see open source projects like OpenStack and Open DayLight play increasingly important roles in the transformation of networks.

Brandon Collings, JDSU's CTO for communications and commercial optical products

The announcements of integrated photonics for coherent CFP2s was an important development in the 100 Gig progression. While JDSU did not make an announcement at OFC, we are similarly engaged with our customers on pluggable approaches for coherent 100 Gig.

I would like to see convergence around 400 Gig client interface standards

There is a lack of appreciation of the data centre operators who aren’t big household names. While the mega data centre operators have significant influence and visibility, the needs of the numerous, smaller-sized operators are largely under-represented.

I would like to see convergence around 400 Gig client interface standards. Lots of complex technology here, challenges to solve and options to do so. But ambiguity in these areas is typically detrimental to the overall industry.

Mike Freiberger, principal member of technical staff, Verizon

The emergence of 100 Gig for metro, access, and data centre reach optics generated a lot of contentious debate. Maybe the best way forward as an industry isn’t really solidified just yet.

What did I learn? Verizon is a leader in wireless backhaul and is growing its options at a rate faster than the industry.

The two developments that caught my attention are 100 Gig short-reach and above-100-Gig research. 100 Gig short-reach because this will set the trigger point for the timing of 100 Gig interfaces really starting to sell in volume. Research on data rates faster than 100 Gig because price-per-bit always has to come downward.

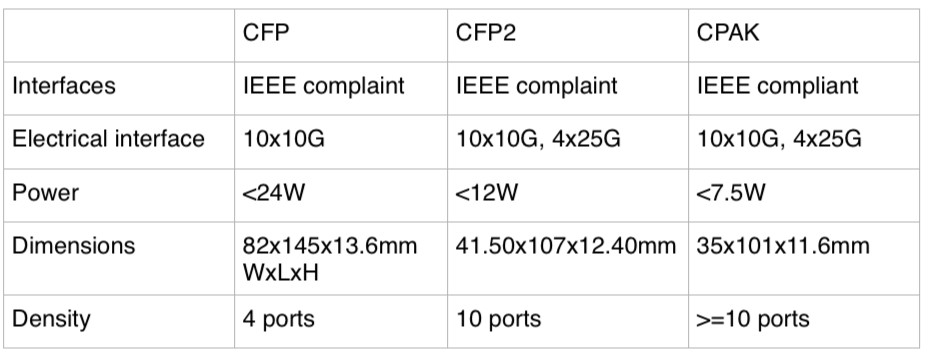

Does Cisco Systems' CPAK module threaten the CFP2?

Cisco Systems has been detailing over recent months its upcoming proprietary optical module dubbed CPAK. The development promises to reduce the market opportunity for the CFP2 multi-source agreement (MSA) and has caused some disquiet in the industry.

Source: Cisco Systems, Gazettabyte, see comments

"The CFP2 has been a bit slow - the MSA has taken longer than people expected - so Cisco announcing CPAK has frightened a few people," says Paul Brooks, director for JDSU's high speed transport test portfolio.

Brooks speculates that the advent of CPAK may even cause some module makers to skip the CFP2 and go straight to the smaller CFP4 given the time lag between the two MSAs is relatively short.

The CPAK module, smaller than the CFP2 MSA and three quarters its volume, has not been officially released and Cisco will not comment on the design but in certain company presentations the CPAK is compared with the CFP. The details are shown in the table above, with the CFP2’s details added.

The CPAK is the first example of Cisco's module design capability following its acquisition of silicon photonics player, Lightwire.

The development of the module highlights how the acquisition of core technology can give an equipment maker the ability to develop proprietary interfaces that promise costs savings and differentiation. But it also raises a question mark regarding the CFP2 and the merit of MSAs when a potential leading customer of the CFP2 chooses to use its own design.

"The CFP2 has been a bit slow - the MSA has taken longer than people expected - so Cisco announcing CPAK has frightened a few people"

"The CFP2 has been a bit slow - the MSA has taken longer than people expected - so Cisco announcing CPAK has frightened a few people"

Paul Brooks, JDSU

Industry analysts do not believe it undermines the CFP2 MSA. “I believe there is business for the CFP2,” says Daryl Inniss, practice leader, Ovum Components. “Cisco is shooting for a solution that has some staying power. The CFP2 is too large and the power consumption too high while the CFP4 is too small and will take too long to get to market; CPAK is a great compromise.”

That said, Inniss, in a recent opinion piece entitled: Optical integration challenges component/OEM ecosystem, writes:

“Cisco’s Lightwire acquisition provides another potential attack on the traditional ecosystem. Lightwire provides unique silicon photonics based technology that can support low power consumption and high-density modules. Cisco may adopt a proprietary transceiver strategy to lower cost, decrease time to market, and build competitive barriers. It need not go through the standards process, which would enable its competitors and provide them with its technology. Cisco only needs to convince its customers that it has a robust supply chain and that it can support its product.”

Vladimir Kozlov, CEO of market research firm, LightCounting, is not surprised by the development. “Cisco could use more proprietary parts and technologies to compete with Huawei over the next decade,” he says. “From a transceiver vendor perspective, custom-made products are often more profitable than standard ones; unless Cisco will make everything in house, which is unlikely, it is not bad news.”

JDSU has just announced that its ONT-100G test set supports the CFP2 and CFP4. The equipment will also support CPAK. "We have designed a range of adaptors that allows us to interface to other optics including one very large equipment vendor's - Cisco's - own CFP2-like form factor," says Brooks.

However, Brooks still expects the industry to align on a small number of MSAs despite the advent of CPAK. "The majority view is that the CFP2 and CFP4 will address most people's needs," says Brooks. "Although there is some debate whether a QSFP2 may be more cost effective than the CFP4." The QSFP2 is the next-generation compact follow-on to the QSFP that supports the 4x25Gbps electrical interface.

The CFP2 pluggable module gains industry momentum

Finisar and Oclaro unveiled their first CFP2 optical transceiver products at the recent ECOC exhibition in Amsterdam. JDSU also announced that its ONT-100G test equipment now supports the latest 100Gbps module form factor.

Source: Oclaro

Source: Oclaro

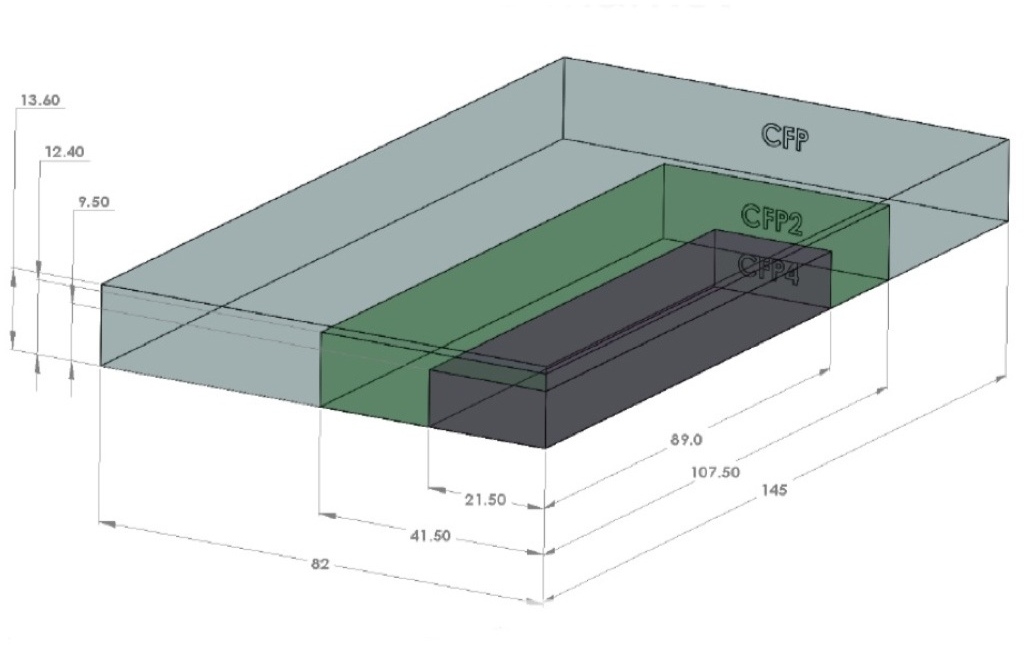

The CFP2 is the follow-on module to the CFP, supporting the IEEE 100 Gigabit Ethernet and ITU OTU4 standards. It is half the size of the CFP (see image) and typically consumes half the power. Equipment makers can increase the front-panel port density from four to eight by migrating to the CFP2.

Oclaro also announced a second-generation CFP supporting the 100GBASE-LR4 10km and OTU4 standards that reduces the power consumption from 24W to 16W. The power saving is achieved by replacing a two-chip silicon-germanium 'gearbox' IC with a single CMOS chip. The gearbox translates between the 10x10Gbps electrical interface and the 4x25Gbps signals interfacing to the optics.

The CFP2, in contrast, doesn’t include the gearbox IC.

"One of the advantages of the CFP2 module is we have a 4x25Gbps electrical interface," says Rafik Ward, vice president of marketing at Finisar. "That means that within the CFP2 module we can operate without the gearbox chip." The result is a compact, lower-power design, which is further improved by the use of optical integration.

"That 2.5x faster [interface of the CFP2] equates to about a 6x greater difficulty in signal integrity issues, microwave techniques etc"

Paul Brooks, JDSU

The transmission part of the CFP module typically comprises four externally modulated lasers (EMLs), each individually cooled. The four transmitter optical sub-assemblies (TOSAs) then interface to a four-channel optical multiplexer.

Finisar's CFP2 design uses a single TOSA holding four distributed feedback (DFB) lasers, a shared thermo-electric cooler and the multiplexer. The result of using DFBs and an integrated TOSA is that Finisar's CFP2 consumes just 8W.

Oclaro uses photonic integration on the receiver side, integrating four receiver optical sub-assemblies (ROSAs) as well as the optical demultiplexer into a single design, resulting in a 12W CFP2.

At ECOC, Oclaro demonstrated interoperability between its latest CFP and the CFP2. “It shows that the new modules will talk to existing ones,” says Robert Blum, director of product marketing for Oclaro's photonic components.

Meanwhile JDSU demonstrated its ONT-100G test set that supports the CFP2 and CFP4 MSAs.

"Initially the [test set] applications are focused on those doing the fundamental building blocks [for the 100G CFP2] – chip vendors, optical module vendors, printed circuit board developers," says Paul Brooks, director for JDSU's high speed transport test portfolio. "We will roll out more applications within the year that cover early deployment and production."

The standards-based client-side interfaces is an attractive market for test and measurement companies. For line-side optical transmission, much of the development work is proprietary such that developing a test set to serve vendors' proprietary solutions is not feasible.

The biggest engineering challenge for the CFP2 is its adoption of high-speed 25Gbps electrical interfaces. "The CFP was based on third generation, mature 10 Gig I/O [input/output]," says Brooks. "To get to cost-effective CFP2 [modules] is a very big jump: that 2.5x faster [interface] equates to about a 6x greater difficulty in signal integrity issues, microwave techniques etc."

The company says that what has been holding up the emergence of the CFP2 module has been the 104-pin connector: "The pluggable connector is the big headache," says Brooks. "The expectation is that very soon we should get some early connectors."

The test equipment also supports developers of the higher-density CFP4 module, and other form factors such as the QSFP2.

JDSU will start shipping its CFP2 test equipment in the first quarter of 2013.

Oclaro's second-generation CFP and the CFP2 transceivers are sampling, with volume production starting in early 2013.

Finisar's CFP2 LR4 product will sample in 2012 and enter volume production in 2013.

JDSU's Brandon Collings on silicon photonics, optical transport & the tunable SFP+

JDSU's CTO for communications and commercial optical products, Brandon Collings, discusses reconfigurable optical add/drop multiplexers (ROADMs), 100 Gigabit, silicon photonics, and the status of JDSU's tunable SFP+.

"We have been continually monitoring to find ways to use the technology [silicon photonics] for telecom but we are not really seeing that happen”

Brandon Collings, JDSU

Brandon Collings highlights two developments that summarise the state of the optical transport industry.

The industry is now aligned on the next-generation ROADM architecture of choice, while experiencing a ’heavy component ramp’ in high-speed optical components to meet demand for 100 Gigabit optical transmission.

The industry has converged on the twin wavelength-selective switch (WSS) route-and-select ROADM architecture for optical transport. "This is in large networks and looking forward, even in smaller sized networks," says Collings.

In a route-and-select architecture, a pair of WSSes reside at each degree of the ROADM. The second WSS is used in place of splitters and improves the overall optical performance by better suppressing possible interference paths.

JDSU showcased its TrueFlex portfolio of components and subsystems for next-generation ROADMs at the recent European Conference on Optical Communications (ECOC) show. The company first discussed the TrueFlex products a year ago. "We are now in the final process of completing those developments," says Collings.

Meanwhile, the 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) component market is progressing well, says Collings. The issues that interest him include next-generation designs such as a pluggable 100Gbps transmission form factor.

Direct detection and coherent

JDSU remains uncertain about the market opportunities for 100Gbps direct-detection solutions for point-to-point and metro applications. "That area remains murky," says Collings. "It is clearly an easy way into 100 Gig - you don't have to have a huge ASIC developed - but its long-term prospects are unclear."

The price point of 100Gbps direct-detection, while attractive, is competing against coherent transmission solutions which Collings describes as volatile. "As coherent becomes comparable [in cost], the situation will change for the 4x25 Gig [direct detection] quite quickly," he says. "Coherent seems to be the long-term, robust cost-effective way to go, capturing most of the market."

At present, coherent solutions are for long-haul that require a large, power-consuming ASIC. Equally the accompanying optical components - the lasers and modulators - are also relatively large. For the coherent metro market, the optics must become cheaper and smaller as must the coherent ASIC.

"If you are looking to put that [coherent ASIC and optics] into a CFP or CFP2, the problem is based on power; cost is important but power is the black-and-white issue," says Collings. Engineers are investigating what features can be removed from the long-haul solution to achieve the target 15-20W power consumption. "That is pretty challenging from an ASIC perspective and leaves little-to-no headroom in a pluggable," says Collings.

The same applies to the optics. "Is there a lesser set of photonics that can sit on a board that is much lower cost and perhaps has some weaker performance versus today's high-performance long-haul?" says Collings. These are the issues designers are grappling with.

Silicon photonics

Another area in flux is the silicon photonics marketplace. "It is a very fluid and active area," says Collings. "We are not highly active in the area but we are very active with outside organisations to keep track of its progress, its capabilities and its overall evolution in terms of what the technology is capable of."

The silicon photonics industry has shifted towards datacom and interconnect technology in the last year, says Collings. The performance levels silicon photonics achieves are better suited to datacom than telecom's more demanding requirements. "We have been continually monitoring to find ways to use the technology for telecom but we are not really seeing that happen,” says Collings.

Tunable SFP+

JDSU demonstrated its tunable laser in an SFP+ pluggable optical module at the ECOC exhibition.

The company was first to market with the tunable XFP, claiming it secured JDSU an almost two-year lead in the marketplace. "We are aiming to repeat that with the SFP+," says Collings.

The SFP+ doubles a line card's interface density compared to the XFP module. The SFP+ supports both 10Gbps client-side and wavelength-division multiplexing (WDM) interfaces. "Most of the cards have transitioned from supporting the XFP to the SFP+," says Collings. This [having a tunable SFP+] completes that portfolio of capability."

JDSU has provided samples of the tunable pluggable to customers. "We are working with a handful of leading customers and they typically have a preference on chirp or no-chirp [lasers], APD [avalanche photo-diode] or no APD, that sort of thing," says Collings.

JDSU has not said when it will start production of the tunable SFP+. "It won't be long," says Collings, who points out that JDSU has been demonstrating the pluggable for over six months.

The company plans a two-stage rollout. JDSU will launch a slightly higher power-dissipating tunable SFP+ "a handful of months" before the standard-complaint device. "The SFP+ standard calls for 1.5W but for some customers that want to hit the market earlier, we can discuss other options," says Collings.

Further reading

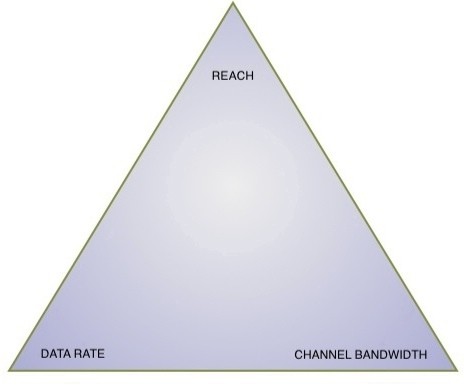

The great data rate-reach-capacity tradeoff

Source: Gazettabyte

Source: Gazettabyte

Optical transmission technology is starting to bump into fundamental limits, resulting in a three-way tradeoff between data rate, reach and channel bandwidth. So says Brandon Collings, JDS Uniphase's CTO for communications and commercial optical products. See the recent Q&A.

This tradeoff will impact the coming transmission speeds of 200, 400 Gigabit-per-second and 1 Terabit-per-second. For each increased data rate, either the channel bandwidth must increase or the reach must decrease or both, says Collings.

Thus a 200Gbps light path can be squeezed into a 50GHz channel in the C-band but its reach will not match that of 100Gbps over a 50GHz channel (Shown on the graph with a hashed line). A wider version of 200Gbps could match the reach to the 100Gbps, but that would probably need a 75GHz channel, says Collings.

For 400Gbps, the same situation arises suggesting two possible approaches: 400Gbps fitting in a 75GHz channel but with limited reach (for metro) or a 400Gbps signal placed within a 125GHz channel to match the reach of 100Gbps over a 50GHz channel.

Optical transmission technology is starting to bump into fundamental limits resulting in a three-way tradeoff between data rate, reach and channel bandwidth.

Optical transmission technology is starting to bump into fundamental limits resulting in a three-way tradeoff between data rate, reach and channel bandwidth.

"Continue this argument for 1 Terabit as well," says Collings. Here the industry consensus suggests a 200GHz-wide channel will be needed.

Similarly, within this compromise, other options are available such as 400Gbps over a 50GHz channel. But this would have a very limited reach.

Collings does not dismiss the possibility of a technology development which would break this fundamental compromise, but at present this is the situation.

As a result there will likely be multiple formats hitting the market which align the reach needed with the minimised channel bandwidth, says Collings.

Q&A with JDSU's CTO

In Part 1 of a Q&A with Gazettabyte, Brandon Collings, JDS Uniphase's CTO for communications and commercial optical products, reflects on the key optical networking developments of the coming decade, how the role of optical component vendors is changing and next-generation ROADMs.

"For transmission components, photonic integration is the name of the game. If you are not doing it, you are not going to be a player"

Brandon Collings (left), JDSU

Q: What are the key optical networking trends of the next decade?

A: The two key pieces of technology at the photonic layer in the last decade were ROADMs [reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexers] and the relentless reduction in size, cost and power of 10 Gigabit transponders.

If you look at the next decade, I see the same trends occupying us.

We are seeing a whole other generation of reconfigurable networks - this whole colourless, directionless, flexible spectrum - all this stuff is coming and it is requiring a complete overhaul of the transport network. We have to support Raman [amplifiers] and we need to support more flexible [optical] channel monitors to deal with flexible spectrum.

We have to overhaul every aspect of the transport system: the components, design, capability, usability and the management. It may take a good eight years for the dust to settle on how that all plays out.

The other piece is transmission size, cost and power.

Right now a 40 Gig or a 100 Gig transponder is large, power-hungry and extremely expensive. Ironically they don't look too different to a 10 Gig transponder in 1998 and you see where that has gone.

You have seen our recent announcement [a tunable laser in an SFP+ optical pluggable module]; that whole thing is now tunable, the size of your pinkie and costs a fraction of what it did in 1998.

I expect that same sort of progression to play out for 100 Gig, and we'll start to get into 400 Gig and some flexible devices in between 100 and 400 Gig.

The name of the game is going to be getting size, cost and power down to ensure density keeps going up and the cost-per-bit keeps going down; all that is enabled by the photonic devices themselves.

Is that what will occupy JDSU for the next decade?

This is what will occupy us at the component level. As you go up one level - and this will impact us more indirectly than it will our customers - we are seeing this ramp of capacity, driven by the likes of video, where the willingness to pay-per-bit is dropping through the floor but the cost to deliver that bit is dropping a lot less.

Operators are caught in the middle and they are after efficiency and cost advantages when operating their networks. We are seeing a re-evaluation of the age-old principles in how networks are operated: How they do protection, how they offer redundancy and how they do aggregation.

People are saying: 'Well, the optical layer is actual fairly cheap compared to the layer two and three. Let's see if we can't ask more of the somewhat cheaper network and maybe pull some of the complexity and requirements out of the upper layers and make that simpler, to end up with an overall cheaper and easier network to operate.'

That is putting a lot of feature requirements on us at the hardware level to build optical networks that are more capable and do more, as well as on our customers that must make that network easier to operate.

That is a challenge that will be a very interesting area of differentiation. There are so many knobs to turn as you try to build a better delivery system optimised over packets, OTN [Optical Transport Network] and photonics.

Are you noting changes among system vendors to become more vertically integrated?

I've heard whisperings of vendors wanting to figure out how they could be more vertically integrated. That's because: 'Well hey, that could make our products cheaper and we could differentiate'. But I think the reality is moving in the opposite direction.

To build differentiated, compelling products, you have to have expertise, capability and technology control all the way down to the materials level almost. Take for example the tunable XFP; that whole thing is enabled by complete technology ownership of an indium-phosphate fab and all the manufacturing that goes around it. That is a herculean effort.

It is tough to say they [system vendors] want to be vertically integrated because to do so effectively you need just a gigantic organisation.

JDSU is vertically integrated. We have an awful lot of technology and we have got a very large manufacturing infrastructure expertise and know-how. We can produce competitive products because for this particular application we use a PLC [planar lightwave circuit], and for that one, gallium arsenide. We can do this because we diversify all this infrastructure, operation and company size across a wide customer base.

Increasingly this is also into adjacent markets like solar, gesture recognition and optical interconnects. These adjacent spaces would not be something that a system vendor would probably want to get into.

The bottom line is that it [the trend] is actually going in the opposite direction because the level, size and scope of the vertical integration would need to be very large and completely non-trivial if system vendors want to be differentiating and compelling. And the business case would not work very well because it would only be for their product line.

"No one says exactly what they will pay for next-gen ROADMs but all can articulate why they want it and what it will do in general terms"

Is this system vendor trend changing the role of optical component players?

Our level of business and our competitors are looking to be more vertically integrated: semiconductors all the way to line cards.

We've proven it with things like our Super Transport Blade that the more you have control over, the more knobs you can turn to create new things when merging multiple functions.

Instead of selling a lot of small black boxes and having the OEMs splice them together, we can integrated those functions and make a more compact and cost-effective solution. But you have to start with the ability to make all those blocks yourself.

Whether it is a line card, a tunable XFP or a 100 Gig module, the more you own and control, the more you can integrate and the more effective your solution will be. This is playing out at the components level because you create more compelling solutions the more functional integration you accomplish.

How do you avoid competing with your customers? If system vendors are just putting cards together, what are they doing? Also, how do you help each vendor differentiate?

It is very true. There are several system vendors that don't build their line cards anymore. They have chosen to do so because they realise that from a design and manufacturing perspective, they don't add much value or even subtract value because we can do more functional integration and they may not be experts in wavelength-selective switch (WSS) construction and various other things.

A fair number of them basically acknowledge that giving these blades to the people who can do them is a better solution for them.

How they differentiate can go two ways.

First, they don't just say: 'Build me a ROADM card.' We work very closely; they are custom design cards for each vendor. They specify what the blade will do and they participate intimately in its design. They make their own choices and put in their own secret sauce.

That means we have very strong partnerships with these operations, almost to the extent that we are part of their development organisations.

The importance of things above the photonic layer collectively is probably more important than the photonic layer. Usability, multiplexing, aggregation, security - all the things that go into the higher levels of a network, this is where system vendors are differentiating.

They can still differentiate at the photonic layer by building strong partnerships with technology engines like JDSU and it allows them to focus more resources at the upper levels where they can differentiate their complete network offering.

"The new generation of reconfigurable networks are not able to reuse anything that is being built today"

"The new generation of reconfigurable networks are not able to reuse anything that is being built today"

Will is happening with regard photonic integration?

For transmission components, photonic integration is the name of the game. If you are not doing it, you are not going to be a player.

If you look at JDSU's tunable [laser] XFP, that is 100% photonic integration. Yes, we build an ASIC to control the device but it is just about getting a little bit extra volume and a little bit more power. The whole thing is about monolithic integration of a tunable laser, the modulator and some power control elements. And that is just 10 Gig.

If you look at 40 Gig, today's modulators are already putting in heavy integration and it is just the first round. These dual-polarisation QPSK modulators, they integrate multiple modulators - one for each polarisation as well as all the polarisation combining functionality, all into one device using waveguide-based integration. Today that is in lithium niobate, which is not a small technology.

100 Gig looks similar, it is just a little bit faster and when you go to 400 Gig, you go multi-carrier which means you make multiple copies of this same device.

So getting these things down in size, cost and power means photonic integration. And just the way 10 Gig migrated from lithium niobate down to monolithic indium phosphide, the same path is going to be followed for 40, 100 and 400 Gig.

It may be more complicated than 10 Gig but we are more advanced with our technology.

Operators are asking for advanced ROADM capabilities while system vendors are willing to provide such features but only once operators will pay for them. Meanwhile, optical component vendors must do significant ROADM development work without knowing when they will see a return. How does JDSU manage this situation and is there a way of working smart here?

I don't think there is a terrifically clever way to look at this other than to say that we speak very carefully and closely with our customers.

These next-generation ROADMs have been going on for three or four years now. We also meet operators globally and ask them very similar questions about when and how and to what extent their interest in these various features [colourless, directionless, contentionless, gridless (flexible spectrum)] lie.

We are a ROADM leader; this is a ROADM question so we'd be making critical decisions if we decided not to invest in this area. We have decided this is going to happen and we have invested very heavily in this space.

It is true; there is not a market there right now.

With anything that is new, if you want to be a market leader you can't enter a market that exists, otherwise you'll be late. So through those discussions with our customers and the trust we have with them, and understanding where their customers and their problems lie, we are confident in that investment.

If you look back at the initial round of ROADMs, the chitchat was the same. When WSSs and ROADMs first came out, the reaction was: 'Wow, these things are really expensive, why would I want this compared to a set of fixed filters which back then cost $100 a pop?".

The commentary on cost was all in that flavour but once they became available and the costs were known, the operators started adopting them because the operators could figure out how they could benefit from the flexibility. Today ROADMs are just about in every network in the world.

We expect the same track to follow. No one is going to say: 'Yes, I’m going to pay twice for this new functionality' because they are being cagey of course.

We are still in the development phase. We are starting to get to the end of that, so the costs and real capabilities - all enabled by the devices we are developing - are becoming clear enough so that our customers can now go to their customers and say: 'Here's what it is, here's what it does and here's what it cost'.

Operators will require time to get comfortable with that and figure out how that will work in their respective networks.

We have seen consistent interest in these next-generation ROADM features. No one says exactly what they will pay for it but all can articulate why they want it and what it will do in general terms.

You say you are starting to get to the end of the development phase of these next-generation ROADMs. What challenges remain?

The new generation of reconfigurable networks are not able to reuse anything that is being built today whether it is from JDSU or Finisar, whether it is MEMS or LCOS (liquid crystal on silicon).

All the devices that are on the shelf today simply are not adequate or you end up with extremely expensive solutions.

This requires us to have a completely new generation of products in the WSS and the multiplexing demultiplexing space - all the devices that will do these functions that were done by AWGs or today by a 1x9 WSS but what is under development, they just look completely different.

They are still WSSs but they use different technologies so without saying exactly what they are and what they do, it is basically a whole new platform of devices.

Can you say when we will know what these look like?

I think the general architecture is fairly well known.

The exact details of the devices and components are still not publicly being talked about but it is the general combination of high-port-count WSSs that support flexible spectrum, fast switching and low loss, and are being used in a route-and-select approach rather than a broadcast-and-select one. That is the node building block.

Then these multicast switches are being built - fibre amplifier arrays; what comprise the colourless, directionless and contentionless multiplexing and demultiplexing.

That is the general architecture - it seems that that is what everyone is settling on. The devices to support that are what the industry is working on.

For Part II of the Q&A with Brandon Collings, click here