Silicon photonics: "The excitement has gone"

The opinion of industry analysts regarding silicon photonics is mixed at best. More silicon photonics products are shipping but challenges remain.

Part 1: An analyst perspective

"The excitement has gone,” says Vladimir Kozlov, CEO of LightCounting Market Research. “Now it is the long hard work to deliver products.”

Dale Murray, LightCounting

Dale Murray, LightCounting

However, he is less concerned about recent setbacks and slippages for companies such as Intel that are developing silicon photonics products. This is to be expected, he says, as happens with all emerging technologies.

Mark Lutkowitz, principal at consultancy fibeReality, is more circumspect. “As a general rule, the more that reality sets in, the less impressive silicon photonics gets to be,” he says. “The physics is just hard; light is not naturally inclined to work on the silicon the way electronics does.”

LightCounting, which tracks optical component and modules, says silicon photonics product shipments in volume are happening. The market research firm cites Cisco’s CPAK transceivers, and 40 gigabit PSM4 modules shipping in excess of 100,000 units as examples. Six companies now offer 40 gigabit PSM4 products with Luxtera, a silicon photonics player, having a healthy start on the other five.

Indium phosphide and other technologies will not step back and give silicon photonics a free ride

LightCounting also cites Acacia with its silicon photonics-based low-power 100 and 400 gigabit coherent modules. “At OFC, Acacia made a fairly compelling case, but how much of its modules’ optical performance is down to silicon photonics and how much is down to its advanced coherent DSP chip is unclear,” says Dale Murray, principal analyst at LightCounting. Silicon photonics has not shown itself to be the overwhelming solution for metro/ regional and long-haul networks to date but that could change, he says.

Another trend LightCounting notes is how PAM-4 modulation is becoming adopted within standards. PAM-4 modulates two bits of data per symbol and has been adopted for the emerging 400 Gigabit Ethernet standard. Silicon photonics modulators work really well with PAM-4 and getting it into standards benefits the technology, says LightCounting. “All standards were developed around indium phosphide and gallium arsenide technologies until now,” says Kozlov.

You would be hard pressed to find a lot of OEMs or systems integrators that talk about silicon photonics and what impact it is going to have

Silicon photonics has been tainted due to the amount of hype it has received in recent years, says Murray. Especially the claim that optical products made in a CMOS fabrication plant will be significantly cheaper compared to traditional III-V-based optical components.

First, Murray highlights that no CMOS production line can make photonic devices without adaptation. “And how many wafers starts are there for the whole industry? How much does a [CMOS] wafer cost?” he says.

“You would be hard pressed to find a lot of OEMs or systems integrators that talk about silicon photonics and what impact it is going to have,” says Lutkowitz. “To me, that has always said everything.”

![]() Mark Lutkowitz, fibeReality LightCounting highlights heterogeneous integration as one promising avenue for silicon photonics. Heterogeneous integration involves bonding III-V and silicon wafers before processing the two.

Mark Lutkowitz, fibeReality LightCounting highlights heterogeneous integration as one promising avenue for silicon photonics. Heterogeneous integration involves bonding III-V and silicon wafers before processing the two.

This hybrid approach uses the III-V materials for the active components while benefitting from silicon’s larger (300 mm) wafer sizes and advanced manufacturing techniques.

Such an approach avoids the need to attach and align an external discrete laser. “If that can be integrated into a WDM design, then you have got the potential to realise the dream of silicon photonics,” says Murray. “But it’s not quite there yet.”

This poses a real challenge for silicon photonics: it will only achieve low cost if there are sufficient volumes, but without such volumes it will not achieve a cost differential

Murray says over 30 vendors now make modules at 40 gigabit and above: “There are numerous module types and more are being added all the time.” Then there is silicon photonics which has its own product pie split. This poses a real challenge for silicon photonics: it will only achieve low cost if there are sufficient volumes, but without such volumes it will not achieve a cost differential.

“Indium phosphide and other technologies will not step back and give silicon photonics a free ride, and are going to fight it,” says Kozlov. Nor is it just VCSELs that are made in high volumes.

LightCounting expects over 100 million indium phosphide transceivers to ship this year. Many of these transceivers use distributed feedback (DFB) lasers and many are at 10 gigabit and are inexpensive, says Kozlov.

For FTTx and GPON, bi-directional optical subassemblies (BOSAs) now cost $9, he says: “How much lower cost can you get?”

Reporting the optical component & module industry

LightCounting recently published its six-monthly optical market research covering telecom and datacom. Gazettabyte interviewed Vladimir Kozlov, CEO of LightCounting, about the findings.

When people forecast they always make a mistake on the timeline because they overestimate the impact of new technology in the short term and underestimate in the long term

Q: How would you summarise the state of the optical component and module industry?

VK: At a high level, the telecom market is flat, even hibernating, while datacom is exceeding our expectations. In datacom, it is not only 40 and 100 Gig but 10 Gig is growing faster than anticipated. Shipments of 10 Gigabit Ethernet (GbE) [modules] will exceed 1GbE this year.

The primary reason is data centre connectivity - the 'spine and leaf' switch architecture that requires a lot more connections between the racks and the aggregation switch - that is increasing demand. I suspect it is more than just data centres, however. I wouldn't be surprised if enterprises are adopting 10GbE because it is now inexpensive. Service providers offer Ethernet as an access line and use it for mobile backhaul.

Can you explain what is causing the flat telecom market?

Part of the telecom 'hibernation' story is the rapidly declining SONET/SDH market. The decline has been expected but in fact it had been growing up till as recently as two years ago. First, 40 Gigabit OC-768 declined and then the second nail in the coffin was the decline in 10 Gig sales: 10GbE is all SFP+ whereas 0C-192 SONET/SDH is still in the XFP form factor.

The steady dense WDM module market and the growth in wireless backhaul are compensating for the decline in SONET/SDH market as well as the sharp drop this year in FTTx transceiver and BOSA (bidirectional optical sub assembly) shipments, and there is a big shift from transceivers to BOSAs.

LightCounting highlights strong growth of 100G DWDM in 2013, with some 40,000 line card port shipments expected this year. Yet LightCounting is cautious about 100 Gig deployments. Why the caution?

We have to be cautious, given past history with 10 Gig and 40 Gig rollouts.

If you look at 10 Gig deployments, before the optical bubble (1999-2000) there was huge expected demand before the market returned to normality, supporting real traffic demand. Whatever 10 Gig was installed in 1999-2000 was more than enough till 2005. In 2006 and 2007 10 Gig picked up again, followed by 40 Gig which reached 20,000 ports in 2008. But then the financial crisis occurred and the 40 Gig story was interrupted in 2009, only picking up from 2010 to reach 70,000 ports this year.

So 40 Gig volumes are higher than 100 Gig but we haven't seen any 40 Gig in the metro. And now 100 Gig is messing up the 40G story.

The question in my mind is how much metro is a bottleneck today? There may be certain large cities which already require such deployments but equally there was so much fibre deployed in metropolitan areas back in the bubble. If fibre cost is not an issue, why go into 100 Gig? The operator will use fibre and 10 Gig to make more money.

CenturyLink recently announced its first customer purchasing 100 Gig connections - DigitalGlobe, a company specialising in high-definition mapping technology - which will use 100 Gig connectivity to transfer massive amounts of data between its data centers. This is still a special case, despite increasing number of data centers around the world.

There is no doubt that 100 Gig will be a must-have technology in the metro and even metro-access networks once 1GbE broadband access lines become ubiquitous and 10 Gig will be widely used in the access-aggregation layer. It is starting to happen.

So 100 Gigabit in the metro will happen; it is just a question of timing. Is it going to be two to three years or 10-15 years? When people forecast they always make a mistake on the timeline because they overestimate the impact of new technology in the short term and underestimate in the long term.

LightCounting highlights strong sales in 10 Gig and 40 Gig within the data centre but not at 100 Gig. Why?

If you look at the spine and leaf architecture, most of the connections are 10 Gig, broken out from 40 Gig optical modules. This will begin to change as native 40GbE ramps in the larger data centres.

If you go to super-spine that takes data from aggregation to the data centre's core switches, there 100GbE could be used and I'm sure some companies like Google are using 100GbE today. But the numbers are probably three orders of magnitude lower than in a spine and leaf layers. The demand for volume today for 100GbE is not that high, and it also relates to the high price of the modules.

Higher volumes reduce the price but then the complexity and size of the [100 Gig CFP] modules needs to be reduced as well. With 10 Gig, the major [cost reduction] milestone was the transition to a 10 Gig electrical interface. It has to happen with 100 Gig and there will be the transition to a 4x25Gbps electrical interface but it is a big transition. Again, forget about it happening in two-three years but rather a five- to 10-year time frame.

I suspect that one reason for Google offerings of 1Gbps FTTH services to a few communities in the U.S. is to find out what these new application are, by studying end-user demand

You also point out the failure of the IEEE working group to come up with a 100 GbE solution for the 500m-reach sweet spot. What will be the consequence of this?

The IEEE is talking about 400GbE standards now. Go back to 40GbE that was only approved some three years, the majority of the IEEE was against having 40GbE at all, the objective being to go to 100GbE and skip 40GbE altogether. At the last moment a couple of vendors pushed 40GbE. And look at 40GbE now, it is [deployed] all over the place: the industry is happy, suppliers are happy and customers are happy.

Again look at 40GbE which has a standard at 10km. If you look at what is being shipped today, only 10 percent of 40GBASE-LR4 modules are compliant with the standard. The rest of the volume is 2km parts - substandard devices that use Fabry-Perot instead of DFB (distributed feedback) lasers. The yields are higher and customers love them because they cost one tenth as much. The market has found its own solution.

The same thing could happen at 100 Gig. And then there is Cisco Systems with its own agenda. It has just announced a 40 Gig BiDi connection which is another example of what is possible.

What will LightCounting be watching in 2014?

One primary focus is what wireline revenues service providers will report, particularly additional revenues generated by FTTx services.

AT&T and Verizon reported very good results in Q3 [2013] and I'm wondering if this is the start of a longer trend as wireline revenues from FTTx pick up, it will give carriers more of an incentive to invest in supporting those services.

AT&T and Verizon customers are willing to pay a little more for faster connectivity today, but it really takes new applications to develop for end-user spending on bandwidth to jump to the next level. Some of these applications are probably emerging, but we do not know what these are yet. I suspect that one reason for Google offerings of 1Gbps FTTH services to a few communities in the U.S. is to find out what these new application are, by studying end-user demand.

A related issue is whether deployments of broadband services improve economic growth and by how much. The expectations are high but I would like to see more data on this in 2014.

Optical transport to grow at a 10% CAGR through 2017

- Global optical transport market to reach US $13bn in 2017

- 100 Gigabit to grow at a 75% CAGR

"I won't be surprised if it [100 Gig] grows even faster"

"I won't be surprised if it [100 Gig] grows even faster"

Jimmy Yu, Dell'Oro Group

The Dell'Oro Group forecasts that the global optical transport market will grow to US $13 billion in 2017, equating to a 10-percent compound annual growth rate (CAGR).

In 2012 SONET/SDH sales declined by over 20 percent, greater than Dell'Oro expected, while wavelength-division multiplexing (WDM) equipment sales held their own.

Regions

Dell'Oro expects optical transport growth across all the main regions, with no one region dominating. The market research company does foresee greater growth in Europe given the prolonged underspend of recent years.

European operators are planning broadband access investment such as fibre-to-the-cabinet/ VDSL vectoring as well as fibre-to-the-home. "That will drive demand for backhaul bandwidth and that is where WDM fits in well," says Jimmy Yu, vice president, microwave transmission, mobile backhaul and optical transport at Dell'Oro.

Technologies

Forty and 100 Gigabit optical transport will be the main WDM growth areas through 2017. Yu expects 40 Gigabit demand to grow over the forecast period even if the growth rate will taper off due to demand for 100 Gigabit.

The 100 Gigabit market continues to exceed Dell'Oro's forecasted growth. The market research company predicts 100-Gbps wavelength shipments to grow at a 75 percent CAGR over the next five years, accounting for 60 percent of the WDM capacity shipments by 2017. "I won't be surprised if it [100 Gig] grows even faster," says Yu.

"A lot of people wonder why have 40 Gig when there is 100 Gig? But that granularity does help service providers; having 40 Gig and 100 Gig rather than going straight from 10 Gig to 100 Gig," says Yu. The 100 Gig sales span metro and long-haul networks with the latter generating greater revenue due to the systems being pricier. "Forty Gigabit sales were predominantly long haul originally but we are seeing a good chunk of growth in metro as well," says Yu.

The current forecast does not include 400Gbps optical transport sales though Yu does expect sales to start in 2016.

Dell'Oro is seeing sales of 100 Gigabit direct detection but says it will remain a niche market. "We are talking tens of [shipped] units a quarter," says Yu.

There are applications where customers will need links of 80km or several hundred kilometers and will want the lowest cost solution, says Yu: "There is a market for direct detection; it will not be a significant driver for 100 Gig but it will be there."

China and the global PON market

China has become the world's biggest market for passive optical network (PON) technology even though deployments there have barely begun. That is because China, with approximately a quarter of a billion households, dwarfs all other markets. Yet according to market research firm Ovum, only 7% of Chinese homes were connected by year end 2011.

"In 2012, BOSAs [board-based PON optical sub-assemblies] will represent the majority versus optical transceivers for PON ONTs and ONUs"

Julie Kunstler, Ovum

Until recently Japan and South Korea were the dominant markets. And while PON deployments continue in these two markets, the rate of deployments has slowed as these optical access markets mature.

According to Ovum, slightly more than 4 million PON optical line terminals (OLTs) ports, located in the central office, were shipped in Asia Pacific in 2011, of which China accounted for the majority. Worldwide OLT shipments for the same period totaled close to 4.5 million. The fact that in China the ratio of OLT to optical network terminal (ONT), the end terminal at the home or building, deployed is relatively low highlights that in the Chinese market the significant growth in PON end terminals is still to come.

The strength of the Chinese market has helped local system vendors Huawei, ZTE and Fiberhome become leading global PON players, accounting for over 85% of the OLTs sold globally in 2011, says Julie Kunstler, principal analayst, optical components at Ovum. Moreover, around 60% of fibre-to-the-x deployments in Europe, Middle East and Africa were supplied by the Chinese vendors. The strongest non-Chinese vendor is Alcatel-Lucent.

Ovum says that the State Grid China Corporation, the largest electric utility company in China, has begun to deploy EPON for their smart grid trial deployments. PON is preferred to wireless technology because of its perceived ability to secure the data. This raises the prospect of two separate PON lines going to each home. But it remains to be seen, says Kunstler, whether this happens or whether the telcos and utilities share the access network.

"After China the next region that will have meaningful numbers is Eastern Europe, followed by South and Central America and we have already seen it in places like Russia,” says Kunstler. Indeed FTTx deployments in Eastern Europe already exceed those in Western Europe.

EPON and GPON

In China both Ethernet PON (EPON) and Gigabit PON (GPON) are being deployed. Ovum estimates that in 2011, 65% of equipment shipments were EPON while GPON represented 35% GPON in China.

China Telecom was the first of the large operators in China to deploy PON and began with EPON. Ovum is now seeing deployments of GPON and in the 3rd quarter of 2012, GPON OLT deployments have overtaken EPON.

China Mobile, not a landline operator, started deployments later and chose GPON. But these GPON deployments are on top of EPON, says Kunstler: "EPON is still heavily deployed by China Telecom, while China Mobile is doing GPON but it is a much smaller player." Moreover, Chinese PON vendors also supplying OLTs that support EPON and GPON, allowing local decisions to be made as to which PON technology is used.

One trend that is impacting the traditional PON optical transceiver market is the growing use of board-based PON optical sub-assemblies (BOSAs). Such PON optics dispenses with the traditional traditional optical module form factor in the interest of trimming costs.

“A number of the larger, established ODMs [original design manufacturers] have begun to ship BOSA-based PON CPEs,” says Kunstler. In 2012, BOSAs will represent the majority versus optical transceivers for PON ONTs/ONUs.” says Kunstler.

10 Gigabit PON

Ovum says that there has been very few deployments of next generation 10G EPON and XG-PON, the 10 Gigabit version of GPON.

"There have been small amounts of 10G [EPON] in China," says Kunstler. "We are talking hundreds or thousands, not the tens of thousands [of units]."

One reason for this is the relative high cost of 10 Gigabit PON which is still in its infancy. Another is the growing shift to deploy fibre-to-the-home (FTTh) versus fibre-to-the-building deployments in China. 10 Gigabit PON makes more sense in multi-dwelling units where the incoming signal is split between apartments. Moving to 10G EPON boosts the incoming bandwidth by 10x while XG-PON would increase the bandwidth by 4x. "The need for 10 Gig for multi-dwelling units is not as strong as originally thought," says Kunstler.

It is a chicken-and-egg issue with 10G PON, says Kunstler. The price of 10G optics would go down if there was more demand, and if there was more demand, the optical vendors would work on bringing down cost. "10G GPON will happen but will take longer," says Kunstler, with volumes starting to ramp from 2014.

However, Ovum thinks that a stronger market application for 10G PON will be for supporting wireless backhaul. The market research company is seeing early deployments of PON for wireless backhaul especially for small cell sites (e.g. picocells). Small cells are typically deployed in urban areas which is where FTTx is deployed. It is too early to know the market forecast for this application but PON will join the list of communications technologies supporting wireless backhaul.

Challenges

Despite the huge expected growth in deployments, driven by China, challenges remain for PON optical transceiver and chip vendors.

The margins on optics and PON silicon continue to be squeezed. ODMs using BOSAs are putting pricing pressure on PON transceiver costs while the vertical integration strategy of system vendors such as Huawei, which also develops some of its own components squeezes, out various independent players. Huawei has its own silicon arm called HiSilicon and its activities in PON has impacted the chip opportunity of the PON merchant suppliers.

"Depending upon who the customer is, depending upon the pricing, depending on the features and the functions, Huawei will make the decision whether they are using HiSilicon or whether they are using merchant silicon from an independent vendor, for example," says Kunstler.

There has been consolidation in the PON chip space as well as several new players. For example, Broadcom acquired Teknouvs and Broadlight while Atheros acquired Opulan and Atheros was then acquired by Qualcomm. Marvell acquired a very small start-up and is now competing with Atheros and Broadcom. Most recently, Realtek is rumored to have a very low-cost PON chip.

ZTE takes PON optical line terminal lead

ZTE shipped 1.8 million passive optical network (PON) optical line terminals (OLTs) in 2011 to become the leading supplier with 41 percent of the global market, according to Ovum.

"ZTE is co-operating with some Tier 1 operators in Europe and the US for 10GEPON and XGPON1 testing"

"ZTE is co-operating with some Tier 1 operators in Europe and the US for 10GEPON and XGPON1 testing"

Song Shi Jie, ZTE

The market research firm also ranks the Chinese equipment maker as the second largest supplier of PON optical network terminals (ONT), with 28 per cent global market share in 2011.

China now accounts for over half the total fibre-to-the-x (FTTx) deployments worldwide. ZTE says 1.05 million of its OLTs were deploy in China, with 70 percent for the EPON standard and the rest GPON. Overall EPON accounts for 85% of deployments in China. However GPON deployments are growing and ZTE expects the technology to gain market share in China.

There are some 300 million broadband users in China, made up of DSL, fibre-to-the-building (FTTB) and -curb (FTTC), says Song Shi Jie, director of fixed network product line at ZTE.

Of the three main operators, China Telecom is the largest. It is deploying FTTB and is moving to fibre-to-the-home (FTTH) deployments using GPON. China Unicom has a similar strategy. China Mobile is focussed on FTTB and LAN technology; because it is a mobile operator and has no copper line assets it uses LAN cabling for networking within the building.

The split ratio - the number of PON ONTs connected to each OLT - varies depending on the deployment. "In the fibre-to-the-building scenario, the typical ratio is 1:8 or 1:16; for fibre-to-the-home the typical ratio is 1:64," says Song.

ZTE has also deployed 200,000 10 Gigabit EPON (10GEPON) lines in China but none elsewhere, either 10GEPON or XGPON1 (10 Gigabit GPON). "ZTE is co-operating with some Tier 1 operators in Europe and the US for 10GEPON and XGPON1 testing," says Song.

Song attributes ZTE's success to such factors as reduced power consumption of its PON systems and its strong R&D in access.

The vendor says its PON platforms consume a quarter less power than the industry average. Its systems use such techniques as shutting down those OLT ports that are not connected to ONTs. It also employs port idle and sleep modes to save power when there is no traffic. Meanwhile, ZTE has 3,000 engineers engaged in fixed access product R&D.

As for the next-generation NGPON2 being development by industry body FSAN, Song says there are a variety of technologies being proposed but that the picture is still unclear.

ZTE is focussing on three main next-generation PON technologies: wavelength division multiplexing PON (WDM-PON), hybrid time division multiplexing (TDM)/ WDM-PON (or TWDM-PON) and orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM) PON. "We think OFDM PON can provide high security, high bandwidth and easy network maintenance," says Song.

ZTE says that the NGPON2 standard will be mature in 2015 but that commercial deployments will only start in 2018.

Huawei boosts its optical roadmap with CIP acquisition

Huawei has acquired UK photonic integration specialist, CIP Technologies, from the East of England Development Agency (EEDA) for an undisclosed fee. The acquisition gives the Chinese system vendor a wealth of optical component expertise and access to advanced European Union R&D projects.

"By acquiring CIP and integrating the company’s R&D team into Huawei’s own research team, Huawei’s optic R&D capabilities can be significantly enhanced," says Peter Wharton, CEO at the Centre for Integrated Photonics (CIP). CIP Technologies is the trading name of the Centre for Integrated Photonics.

Huawei now has six European R&D centres with the acquisition of CIP.

Huawei now has six European R&D centres with the acquisition of CIP.

CIP Technologies has indium phosphide as well as planar lightwave circuit (PLC) technology which it uses as the basis for its HyBoard hybrid integration technology. HyBoard allows actives to be added to a silica-on-silicon motherboard to create complex integrated optical systems.

CIP has been using its photonic integration expertise to develop compact, more cost-competitive WDM-PON optical line terminal (OLT) and optical network unit (ONU) designs, including the development of an integrated transmitter array.

The company employs 50 staff, with 70% of its work coming from the telecom and datacom sectors. About a third of its revenues are from advanced products and two thirds from technical services.

The CEO of CIP says all current projects for its customers will be carried out as planned but CIP’s main research and development service will be focused on Huawei’s business priorities. “We expect all contracted projects to be completed and current customers are being assisted to find alternate sources of supply," says Wharton.

CIP is also part of several EU Seventh Framework programme R&D projects. These include BIANCHO, a project to reduce significantly the power consumption of optical components and systems, and 3CPO, which is developing colourless and coolerless optical components for low-power optical networks.

Huawei's acquisition will not affect CIP's continuing participation in such projects. "For EU framework and other collaborative R&D projects, the ultimate share ownership does not matter so long as it is a research organisation based in Europe, which CIP will continue to be," says Wharton.

CIP said it had interest from several potential acquirers but that the company favoured Huawei.

What this means

CIP has a rich heritage. It started as BT's fibre optics group. But during the optical boom of 1999-2000, BT shed its unit, a move also adopted by such system vendors as Nortel and Lucent.

The unit was acquired by Corning in 2000 but the acquisition did not prove a success and in 2002 the group faced closure before being rescued by the East of England Development Agency (EEDA).

CIP has always been an R&D organisation in character rather than a start-up. Now with Huawei's ambition, focus and deep pockets coupled with CIP's R&D prowess, the combination could prove highly successful if the acquisition is managed well.

Huawei's acquisition looks shrewd. Optical integration has been discussed for years but its time is finally arriving. The technologies of 40 Gigabit and 100 Gigabit is based on designs with optical functions in parallel; at 400 Gigabit the number of channels only increases.

Optical access will also benefit from photonic integration - from board optical sub-assemblies for GPON and EPON to WDM-PON to ultra dense WDM-PON. China is also the biggest fibre-to-the-x (FTTx) market by far.

A BT executive talking about the operator's 21CN mentioned how system vendors used to ask him repeatedly about Huawei. Huawei, in contrast, used to ask him about Infinera.

Huawei, like all the other systems vendors, has much to do to match Infinera's photonic integrated circuit expertise and experience. But the Chinese vendor's optical roadmap just got a whole lot stronger with the acquisition of CIP.

Further reading:

Reflecting light to save power, click here

Optical components: The six billion dollar industry

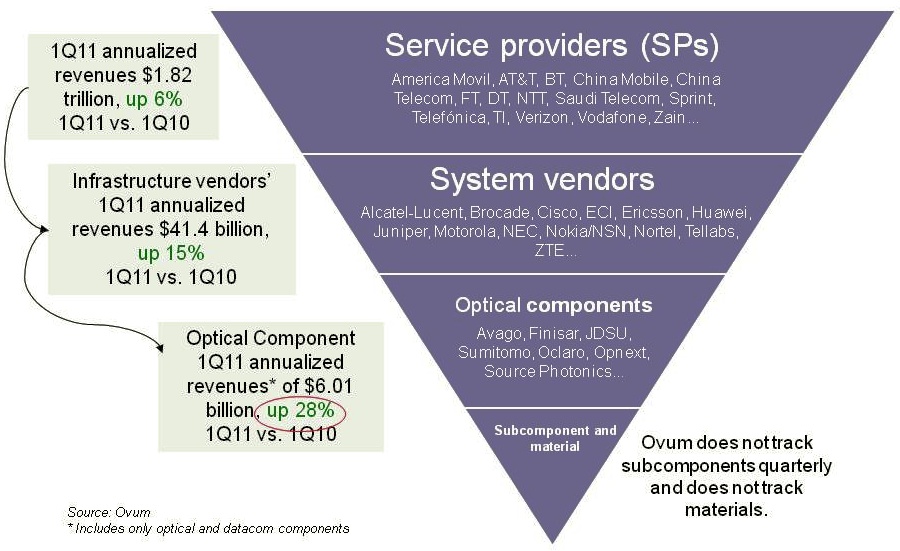

The service provider industry, including wireless and wireline players, is up 6% year-on-year (2Q10 to 1Q11) to reach US $1.82 trillion, according to Ovum. The equipment market, mainly telecom vendors but also the likes of Brocade, has also shown strong growth - up 15% - to reach revenues of over $41.4 billion. But the most striking growth has occurred in the optical components market, up 28%, to achieve revenues of over $6 billion, says the market research firm.

Source: Ovum

Source: Ovum

“This is the first time optical components has exceeded six billion since 2001,” says Daryl Inniss, practice leader, Ovum Components. Moreover, the optical component industry growth has continued over six consecutive quarters with the growth being more than 25% for the past four quarters. “None of the other [two] segments have performed in this way,” says Inniss.

Ovum cites three factors accounting for the growth. Fibre-to-the-x (FTTx) is experiencing strong growth while revenues have entered the market from datacom players from the start of 2010. “The [optical] component recovery was led by datacom,” says Inniss. “We speculate that some of that money came from the Googles, Facebooks and Yahoos!.” A third factor accounting for growth has been optical equipment vendors ordering more long lead-time items than needed – such as ROADMs – to secure supply.

Source: Ovum

Source: Ovum

The second chart above shows the different market segments normalised since the start of 1999. Shown are the capex spending for optical networking, optical networking equipment revenues, optical components and FTTx equipment spending.

Optical networking spending is some 3.5x that of the components. FTTx equipment revenues are lower than the optical component industry’s and is therefore multiplied by 2.25, while capex is 9.2x that of optical equipment. The peak revenue in 2001 is the optical component revenues during the optical boom.

Several points can be drawn from the normalised chart:

- The strong recent growth in FTTx is the result of the booming Chinese market.

- From 2003 to 2008, the overall market showed steady growth, as illustrated by the best-fit line.

- From 2003 to 2008, capex and optical networking revenues were in line, while two thirds of the optical component revenues were due to this telecom spending.

- From 2010 onwards, components deviated from these two other segments due to the datacom spending from new players and the strong growth in FTTx.

- Once the market crashed in early 2009, optical components, networking and capex all fell. FTTx recovered after only one quarter and was followed by optical components. Optical networking and capex, meanwhile, have still not fully recovered when compared with the underlying growth line.

EPON becomes long reach

“Rural [PON deployment] is a tough proposition”

Barry Gray

Moreover, the TK3401 supports up to four such EPONs. The chip does not require changes to EPON’s optical transceivers although wavelength division multiplexing (WDM) transceivers are needed for the greater reach.

The TK3401 sits within what Barry Gray, director of marketing for Teknovus, calls the Intelligent PON Node (IPN). The IPN resides 20km from the subscriber’s optical network unit (ONU), where the PON’s optical line terminal (OLT) normally resides.

On one side of the IPN platform are sockets for up to four EPON OLT transceivers that support the PONs. On the other side are four SFP WDM transceivers that communicate with the central office up to 80km away and where the OLT platform is located. The OLT line card instead of using OLT optics uses WDM transceivers also in the SFP form factor. As such the line card does not require any redesign (see diagram).

Up to four point-to-point fibres can be used to connect the PONs’ traffic to the OLT, or a single fibre and up to 8 lambdas with coarse WDM (CWDM) technology to multiplex four PONs onto a single trunk fibre.

The 256 subscribers are achieved using a PX20+ specified optical transceiver. “It has a 28dB link budget such that going through 8 splitter stages is still sufficient for 2km distances [from the ONUs],” says Gray. “This is ideal for multi-dwelling unit deployments.”

Besides the pluggable optics, the IPN design includes the TK3401, a field programmable gate array (FPGA), and a flash memory.

The TK3401 comprises an EPON ONU media access controller (MAC), microprocessor and on-chip memory. The MAC registers the IPN with the central office OLT to set up remote IPN management and configuration communication links. The on-chip memory holds the firmware that configures the FPGA on start-up. The FPGA implements a crossbar switch to connect traffic from any of the EPONs to any of the WDM ports.

The IPN approach offers other advantages besides the 100km reach and increased subscriber count. It has a power consumption of 20W which means it can be powered from such locations as a telegraph pole. As the PONs are first populated, all four PONs’ traffic can also be aggregated into a single WDM link OLT port, with OLT ports added only when needed. In turn a fibre link can be used for protection with a sub-100ms restoration time.

However, unlike long reach PON or WDM-PON which also offer a 100km reach, the Teknovus scheme still requires the intermediate network node. The node is also active as it must be powered.

Teknovus claims it has strong interest from its IPN-based EPON architecture from operators in Japan and South Korea, while interest in China is for rural PON deployments. “Rural [PON deployment] is a tough proposition for service providers,” says Gray. “There is not the subscriber density and it is more expensive; the same is also true for mobile backhaul.”

The company is demonstrating the IPN to customers.

Click here for Teknovus' IPN presentation and White Paper

Photonic integration: Bent on disruption

“This is a general rule: what starts as a series of parts loosely strung together, if used heavily enough, congeals into a self-contained unit.”

W. Brian Arthur, The Nature of Technology

Infinera's Dave Welch: PICs are fibre-optic's current disruption

Infinera's Dave Welch: PICs are fibre-optic's current disruption

Dave Welch likes to draw a parallel with digital photography when discussing the use of photonic integration for optical networking. “The CMOS photodiode array – a photonic integrated circuit - changed the entire supply chain of photography,” says Welch, the chief strategy officer at Infinera.

Applied to networking, the photonic integrated circuit (PIC) is similar, argues Welch. It benefits system cost by integrating individual optical components but it delivers more. “All the value – inherently harder to pin down - of networking efficiency of a system that isn’t transponder-based,” says Welch.

Just how disruptive a technology the PIC proves to be is unclear but there is no doubting the growing role of optical integration.

“Integration is a key part of our thinking,” says Sam Bucci, vice president, WDM, Alcatel-Lucent’s optics activities. When designing a new platform, Alcatel-Lucent surveys components and techniques to identify disruptive technologies. Even if it chooses to implement functions using discrete components, the system is designed taking into account future integrated implementations.

“We are seeing interest [in photonic integration] across the spectrum," says Stefan Rochus, vice president of marketing and business development at CyOptics. "Long-haul, metro, access and chip-to-chip - everything is in play."

The drivers for optical integration’s greater use are harder to pin down.

Operators must contend with yearly data traffic growth estimated at between 45 to 65 percent yet their revenues are growing modestly. “It’s no secret that the capacity curve - whether the line side or the client side - is growing at an astonishing clip,” says Bucci.

The onus is thus on equipment and component makers to deliver platforms that reduce the transport cost per bit."Delivering more for less," says Graeme Maxwell, vice president of hybrid integration at CIP Technologies. “Space is a premium, power is an issue, operators want performance maintained or improved – all are driving integration.”

Cost is an issue for optical components with yearly price drops of 20 percent being common. “Hitting the cost-curve, we have run out of ways to do that with classic optics,” says Sinclair Vass, commercial director, EMEA at JDS Uniphase.

High-speed optical transmission at 40 and 100 Gigabit per second (Gbps) requires photonic integration though here the issues are as much performance as cost reduction. Indeed, its use can be viewed as the result of the integration between electronics and optics. To address optical signal impairments, chips must work at the edge of their performance, requiring the optical signal to be split into slower, parallel streams. Such an arrangement is ripe for photonic integration.

“It is as if there are two kinds of integration: at the boundary between optics and electronics, and the purely optical planar waveguide stuff,” says Karen Liu, vice president, components and video technologies at market research firm Ovum.

The other market where the full arsenal of optical integration techniques – hybrid and monolithic integration – is being applied is optical transceivers for passive optical networking (PON). Here the sole story is cost.

As old as the integrated circuit

Photonic integration is not new. The idea was first mooted in a 1969 AT&T Bell Labs’ paper that described how multiple miniature optical components could be interconnected via optical waveguides made using thin-film dielectric materials. But so far industry adoption for optical networking has been limited.

"Two kinds of integration: at the boundary between optics and electronics, and the purely optical planar waveguide stuff"

Karen Liu, Ovum

Heavy Reading, in a 2008 report, highlighted the limited progress made in photonic integration in recent years, with the exception of Infinera, a maker of systems based on a dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) 10x10Gbps monolithically integrated PIC.

“Infinera has held very consistently to its original story, including sub-wavelength grooming, and have made progress over time,” says Liu. But she points out a real disruptive impact has not yet been seen: “The problem with the digital camera analogy is that something that is disruptive is not a straight replacement but implies the next step: changing the network architecture, not just how a system is implemented.”

On-off keying to phase modulation

One way operators are accommodating traffic growth is cramming more data down a fibre. It is this trend- from 10Gbps to 40 and 100Gbps lightpaths - that is spurring photonic integration.

“If you look at current 100 Gigabit, it is a bigger configuration than we would like,” says Joe Berthold, Ciena’s vice president of network architecture. Ciena’s first 100Gbps design requires three line cards, taking five inches of rack space, while its second-generation design will fit on a single, two-inch card.

Both 40 and 100Gbps transmissions must also operate over existing networks, matching the optical link performance of 10Gbps despite dispersion being more acute at higher line speeds. To meet the challenge, the industry has changed how it modulates data onto light. Whereas previous speed increments up to 10Gbps used simple on-off keying, 40 and 100Gbps use advanced modulation schemes based on phase, or phase combined with polarisation.

The modulation schemes split the optical signal into parallel paths to lower symbol rates. For example, 40Gbps differential quadrature phase-shift keying (DQPSK) uses two signals that effectively operating at 20 Gigabaud. Halving the rate relaxes the high-speed electronics requirements at the expense of complicating the optical circuitry.

The concept is extended further at 100Gbps. Here polarisation is combined with phase modulation (either DQPSK, or QPSK if coherent detection is used) such that four signals are used in parallel, each operating at 28 Gigabaud.

“The 40/100G area is shaping up to be the equivalent of breaking the sound barrier”

Brad Smith, LightCounting

“Optical integration is becoming a necessity because of 40 and 100 Gigabit [transmission],” says Berthold. “The modulation formats require you to deal with signals in parallel, and using non-integrated components explodes the complexity.”

The Optical Internetworking Forum organisation has chosen dual-polarisation QPSK (DP- QPSK) as the favoured modulation scheme for 100Gbps and has provided integrated transmitter and receiver module guidelines to encourage industry convergence on common components. In contrast, for 40Gbps several designs have evolved: differential phase-shift keying (DPSK) through to DQPSK and DP-QPSK.

Kim Roberts, Nortel's director of optics research, while acknowledging that optical integration benefits system footprint and cost, downplays its overall significance.

For him, the adoption of coherent systems for 40 and 100Gbps – Nortel was first to market with a 40Gbps DP-QPSK system – move the complexity ‘into CMOS’, leaving optics to perform the basic functions. “I don’t see an overwhelming argument for integration,” says Roberts. “It’s useful and shows up in lower cost and smaller designs but it’s not a revolution.”

Meanwhile, optical component companies are responding by integrating various building blocks to address the bulkier 40 and 100Gbps designs.

NeoPhotonics is now shipping two PICs for 40 and 100Gbps receivers: a DQPSK demodulator based on two delay-line interferometers (DLIs) and a coherent mixer for a DP-QPSK receiver.

The DLI, as implied by the name, delays one of the received symbols and compares it with the adjacent received one to uncover the phase-encoded information. This is then fed to a balanced detector - a photo-detector pair. For DQPSK, either two DLIs or a single DLI plus 90-degree hybrid are required along with two balanced receivers.

For 100Gbps, a DP-QPSK receiver has four channels - a polarisation beam splitter separates the two polarisations and each component is mixed with a component from a local reference signal using a 90-degree hybrid mixer. The two hybrid mixers decompose the referenced phase to intensity outputs representing the orthogonal phase components of the signal and the four differential outputs are fed into the four balanced detectors (Click here for OIF document and see Fig 5).

Neophotonics’ coherent mixer integrates monolithically all the demodulation functions between the polarisation beam splitter and the balanced photo-detectors.

The company has both indium phosphide and planar lightwave circuit (PLC) technology integration expertise but chose to implement its designs using PLC technology. “Indium phosphide is good for actives but is not good for passives and it is very expensive,” says Ferris Lipscomb, vice president of marketing at NeoPhotonics.

One benefit of using PLC for demodulation is that the signal path lengths need to have sub-millimeter accuracy to recover phase; implementing a discrete design using fibre to achieve such accuracy is clearly cumbersome.

Another development that reduces size and cost involves the teaming of u2t Photonics, a high-speed photo-detector and indium phosphide specialist, with Optoplex and Kylia, free-space optics DLI suppliers. The result is a compact DPSK receiver that combines the DLI and balanced receiver within one package. Such integration at the package level reduces the size since fibre routeing between separate DLI and detector packages is no longer needed. The receiver also cuts cost by a quarter, says u2t.

Jens Fiedler, vice president sales and marketing at u2t Photonics, acknowledges that the free-space DLI design may not be the most compact design but was chosen based on the status of the various technologies. “We needed to provide a solution and PLC was not ready,” he says.

u2t Photonics is investigating a waveguide-based DLI solution and is considering indium phosphide and, intriguingly, gallium arsenide. “Indium phosphide has the benefit of integrating the DLI with the balanced detector,” says Fiedler. “There are benefits but also technical challenges [with indium phosphide].”

At ECOC 2009 in September, u2t announced a multi-source agreement (MSA) with another detector specialist, Picometrix, which supports the OIF’s DP-QPSK coherent receiver design. The MSA defines the form factor, pin functions and locations, and functionality of the receiver package holding the balanced detectors, targeted at transponder and line card designs.

Photonic integration for high-speed transmissions is not confined to the receiver. Oclaro has developed a 40Gbps DQPSK monolithic modulator. Implemented in indium phosphide, the modulator could even be monolithically integrated with the laser but Oclaro has said that there are performance benefits such as signal strength in keeping the two separate.

Infinera, meanwhile, eschews transponders in favour of its 100Gbp indium phosphide-based PIC.

Take your PIC

Take your PIC

In September it announced a system for submarine transmission, achieved by adding a semiconductor optical amplifier (SOA) to its 10-channel transmitter and receiver PIC pair. “We are now at a point when the performance of the PIC is a good as the performance of discretes,” says Welch.

In March the company announced its next-gen PIC design - a 10x40Gbps DP-DQPSK transmitter and receiver chip pair. This is a significantly more complex design, with the transmitter integrating the equivalent of 300 optical functions; Infinera’s 10x10G transmitter PIC integrates 50.

Infinera favoured DP-DQPSK rather than the OIF-backed DP-QPSK as the latter requires significant chip support to perform the digital processing for signal recovery for each channel. Given the PIC’s 10 channels, the power consumption would be prohibitive. Instead Infinera tackles dispersion using a simpler, power-efficient optical design.

Is there a performance hit using DP-DQPSK? “There is a nominal industry figure, 1,600km reach being a good number,” says Welch. “For ultra long haul, we absolutely meet that.”

Infinera has still to launch the 400Gbps PIC whereas transponder-based system vendors have been shipping systems delivering 40Gbps lightpaths for several years. But the company says that the PIC exists, is working and all that is left is “managing it onto the manufacturing line”.

“The 40/100G area is shaping up to be the equivalent of breaking the sound barrier,” says Brad Smith, senior vice president at optical transceiver market research firm LightCounting. He questions the likely progress of optical component assemblies given they have far too many technical, cost, and size limitations. “PICs and silicon photonics have a shot at changing the game,” he says. “But the capital investment is very high with relatively low associated volumes.”

PON: an integration battleground

PON is one market where both hybrid and monolithic integration are competing with discrete-based optical transceiver designs. “Here the whole issue is cost – it’s not performance,” says Liu.

When Finisar entered the GPON transceiver market two years ago it conducted as survey as to what was available. What it found was revealing. “No-one was using the newer technologies, it was all the traditional technique based on TO cans,” said Julie Eng, vice president of optical engineering at Finisar. Mounted within the TO cans are active components such as a distributed-feedback (DFB) or Fabry-Perot laser, or a photo-detector. This is what integrated optics - whether a hybrid design basedon PLC or an indium phosphide monolithic PIC - is looking to displace.

“There is a huge infrastructure – millions of TO cans - and the challenge for hybrid and monolithic integration is that they are chasing a cost-curve that continues to come down,” says Eng.

According to NeoPhotonics’ Lipscomb, it is also hard for monolithic or hybrid integration to match the specifications of TO cans. “FTTx is similar to ROADMs, once one technology is established it is difficult for another to displace it,” he says.

But this is exactly what Canadian firms Enablence Technologies and OneChip Photonics are aiming to do.

Enablence, a hybrid integration specialist, uses a PLC-based design for PON. Onto the PLC are coupled a laser and detector for a diplexer PON design, or for a triplexer - two detectors. A common PLC optical platform is used for the different standards – Broadband PON, Ethernet PON (EPON) and Gigabit PON (GPON) - boosting unit volumes. All that is changed are the actives, for example a Fabry-Perot laser is added to the platform for 10km-reach EPON or a DFB for 20km GPON transceivers. Wavelength filtering is also performed using the PLC waveguides.

“Competing with TO cans in PON is challenging,” admits Matt Pearson, vice president of engineering at Enablence. That’s because the discrete design’s assembly is highly manual, benefiting from Far Eastern labour rates.

A hybrid approach brings several benefits, says Pearson: packaging a highly-integrated device is simpler compared to the numerous piece parts using TO cans. “It is also possible to seal at the chip level not at the module level, such that non-hermetic package can be used,” says Pearson.

There is also an additional, albeit indirect, benefit. Using hybrid integration, Enablence can reuse its intellectual property. “The same wafer process used for PON can be used for 40 and 100 Gig applications,” says Pearson. “These promise better margins as they are higher-end products.”

Enablence claims hybrid also scores when compared to monolithic integration. A hybrid design doesn’t sacrifice system performance: optimised lasers and detectors are used to meet the design specification. In contrast, performance compromises are inevitable for each of the optical functions – lasers, detectors, filtering - given that all are made in a single manufacturing process.

OneChip's EPON diplexer PIC seated on a silicon optical bench and showing the connecting fibreOneChip counters by noting the cost benefits of monolithic integration: its EPON-based transceivers are claimed to be 25 percent cheaper than competing designs. “It is not just integration [and the compact design] but there is a completely different automated packaging of the transceiver,” says Andy Weirich, OneChip’s vice president of product line management.

OneChip's EPON diplexer PIC seated on a silicon optical bench and showing the connecting fibreOneChip counters by noting the cost benefits of monolithic integration: its EPON-based transceivers are claimed to be 25 percent cheaper than competing designs. “It is not just integration [and the compact design] but there is a completely different automated packaging of the transceiver,” says Andy Weirich, OneChip’s vice president of product line management.

The company also argues that all three approaches each have their particular compromises, and that all its optical functions are high performance: the company uses a DFB laser and an optically pre-amplified photo-detector for its designs. “If you can get the best specification with no additional cost, what advantage is there of buying a cheaper laser?” says Weirich.

“Inelegant as it is, the TO can’s performance is quite good as is its cost,” says Ovum’s Liu. What is evident here is how each company is coming from a different direction, she says: “Enablence points out that a discrete design is not a platform with a future whereas the likes of Finisar are saying: do we care?”

That said, Finisar’s Eng does expect photonic integration to be increasingly used for PON: “Its time will come, we are just not at that time now.”

Photonic integration will also be used in emerging standards such as wavelength division multiplexing PON (WDM-PON), especially at the head-end where the optical line terminal (OLT) resides.

“WDM-PON is very much point-to-point even though the fibre is shared like a normal PON,” says David Smith, CTO at CIP Technologies. “When you get in the central office there is a mass of equipment just like point-to-point [access].” The opportunity is to integrate the OLT’s lasers – typically 32 or 64 - into arrays, which will also save power, says Smith.

Tunables and interconnects

Other market segments are benefiting from photonic integration besides 40 and 100Gbps transmission and PON.

JDS Uniphase’s XFP module-based tunable laser is possible by monolithically integration the laser and Mach-Zehnder modulator. Not only is the resulting tunable laser compact – it is a few millimeters long - such that it and the associated electronics fit within the module, but the power consumption is below the pluggable’s 3.5W ceiling.

JDS Uniphase has also developed a compact optical amplifier that extends long-haul optical transmission before electrical signal regeneration is needed. A PLC chip is used to replace some 50 discrete optical components including isolators, photo-detectors for signal monitoring, a variable pump splitter and tunable gain-flattening and tilt filters.

The result is an amplifier halved in size and simpler to make since the PLC removes the need to route and splice fibres linking the discretes. Moreover, JDS Uniphase can use different PLC manufacturing masks to enable specific functions for particular customers. This is the closest the optical world gets to a programmable IC.

Towards 1 terabit-per-second interfaces: a hybrid integrated prototype as part of an NIST project involving CyOptics and Kotura. Click on the photo for more details

Towards 1 terabit-per-second interfaces: a hybrid integrated prototype as part of an NIST project involving CyOptics and Kotura. Click on the photo for more details

The emerging 40 and 100 Gigabit Ethernet interface standards are another area suited for future integration. “What is driving optical integration here is size,” says Eng. “How do you fit 100Gigabit in a 3x5 inch module? That is cutting the size in half and will require a lot of R&D effort.”

In particular, optical integration will be needed to implement the 40GBASE-LR4 Gigabit Ethernet standard within a QSFP module. “You can’t fit four TO can lasers and four TO can receivers into a QSFP module,” says Rochus.

It is the 40 and 100 Gigabit Ethernet market that is the higher end market that also interests Enablence. “The drivers for PON and 100 Gigabit may be different but it’s the same PLC technology,” says Pearson. A PON diplexer may integrate one laser and one detector, for 100G it’s ten lasers and ten detectors, he says.

What next?

“Bandwidth growth is forcing us to consider architectures not considered before,” says Alcatel Lucent’s Bucci. The system vendor is accelerating its integration activities, whether it is integrating two wavelength-selective switches in a package or developing ‘electro-optic engines’ that combine advanced modulation optics and digital signal processing.

Moreover, operators themselves are more open to networking change due to the tremendous challenges they face, says Bucci: “They are being freed to do more, to take more risks.”

Welch believes one significant development that PICs will enable – perhaps a couple of years out - is adding and dropping at the packet level, at every site in the core network. “This will enable lots of reconfigurability and much finer granularity, delivering another level of networking efficiency,” he says.

Is this leading to disruption - the equivalent of digital cameras on handsets? Time will tell.

Click here for a mindmap of this article in PDF form.

Next-Gen PON: An interview with BT

Peter Bell, Access Platform Director, BT Innovate & Design

Peter Bell, Access Platform Director, BT Innovate & Design

Q: The status of 10 Gigabit PON – 10G EPON and 10G GPON (XG-PON): Applications, where it will be likely be used, and why is it needed?

PB: IEEE 10G EPON: BT not directly involved but we have been tracking it and believe the standard is close to completion (gazettabyte: The standard was ratified in September 2009.)

ITU-T 10Gbps PON: This has been worked on in the Full Service Access Network group (FSAN) where it became known as XG-PON. The first version XG-PON1 is 10Gbps downstream and 2.5Gbps upstream and work has started on this in ITU-T with a view to completion in the 2010 timeframe. The second version XG-PON2 is 10Gbps symmetrical and would follow later.

Not specific to BT’s plans but an operator may use 10Gbps PON where its higher capacity justified the extra cost. For example: business customers, feeding multi-dwelling units (MDUs) or VDSL street cabinets

Q: BT's interest in WDM-PON and how would it use it?

PB: BT is actively researching WDM-PON. In a paper presented at ECOC '09 conference in Vienna (24th September 2009) we reported the operation of a compact DWDM comb source on an integrated platform in a 32-channel, 50km WDM-PON system using 1.25Gbps reflective modulation.

We see WDM-PON as a longer term solution providing significantly higher capacity than GPON. As such we are interested in the 1Gbps per wavelength variants of WDM-PON and not the 100Mbps per wavelength variants.

Q: FSAN has two areas of research regarding NG PON: What is the status of this work?

PB: NG-PON1 work is focussed on 10 Gbps PON (known as XG-PON) and has advanced quite quickly into standardisation in ITU-T.

NG-PON2 work is longer term and progressing in parallel to NG-PON1

Q: BT's activities in next gen PON – 10G PON and WDM-PON?

PB: It is fair to say BT has led research on 10Gbps PONs. For example an early 10Gbps PON paper by Nesset et al from ECOC 2005 we documented the first, error-free physical layer transmission at 10Gbps, over a 100km reach PON architecture for up and downstream.

We then partnered with vendors to achieve early proof-of-concepts via two EU funded collaborations.

Firstly in MUSE we collaborated with NSN et al to essentially do first proof-of-concept of what has become known as XG-PON1 (see attached long reach PON paper).

Secondly, our work with NSN, Alcatel-Lucent et al on 10Gbps symmetrical hybrid WDM/TDMA PONs in EU project PIEMAN has very recently been completed.

Q: What are the technical challenges associated with 10G PON and especially WDM-PON?

For 10Gbps PONs in general the technical challenges are:

- Achieving the same loss budgets - reach - as GPON despite operating at higher bitrate and without pushing up the cost.

- Coexistence on same fibres as GPON to aid migration.

- For the specific case of 10Gbps symmetrical (XG-PON2) the 10 Gbps burst mode receiver to use in the headend is especially challenging. This has been a major achievement of our work in PIEMAN.

For WDM-PONs the technical challenges are:

- Reducing the cost and footprint of the headend equipment (requires optical component innovation)

- Standardisation to increase volumes of WDM-PON specific optical components thereby reducing costs.

- Upgrade from live GPON/EPON network to WDM-PON (e.g. changing splitter technology)

Q: There are several ways in which WDM-PON can be implemented, does BT favour one and why, or is it less fussed about the implementation and more meeting its cost points?

PB: We are only interested in WDM-PONs giving 1Gbps per wavelength or more and not the 100Mbps per wavelength variants. In terms of detailed implementation we would support the variant giving lowest cost, footprint and power consumption.

Q: What has been happening with BT's Long Reach PON work

PB: We have done lots of work on the long reach PON concept which is summarised in a review published paper from IEEE JLT and includes details of our work to prototype a next-generation PON capable of 10Gbps, 100km reach and 512-way split. This includes EU collaborations MUSE and PIEMAN

From a technical perspective, Class B+ and C+ GPON (G.984.2) could reach a high percentage of UK customers from a significantly reduced number of BT exchanges. Longer reach PONs would then increase the coverage further.

Following our widely published work in amplified GPON, extended reach GPON has now been standardised (G.984.6) to have 60 km reach and 128-way split, and some vendors have early products. And 10Gbps PON standards are expected to have same reach as GPON.