Adding an extra dimension to ROADM designs

U.K. start-up ROADMap Systems, a developer of wavelength-selective switch technology, has completed a second round of funding. The amount is undisclosed but the start-up is believed to have raised several million dollars to date.

Karl HeeksThe company will use the funding to develop a prototype of its two-dimensional (2D) optical beam-steering technique to integrate 24 wavelength-selective switches (WSSes) within a single platform.

Karl HeeksThe company will use the funding to develop a prototype of its two-dimensional (2D) optical beam-steering technique to integrate 24 wavelength-selective switches (WSSes) within a single platform.

The WSS is a key building block used within reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexers (ROADMs).

The company’s WSS technology uses liquid crystal on silicon (LCOS) technology, the basis of existing WSS designs from the likes of Finisar and Lumentum. However, the start-up has developed a way to steer beams in 2D whereas current WSSes operate in a single dimension only.

The Cambridge-based company’s pre-production prototype will integrate 24,1x12 WSSes within a single package. The platform promises service providers ROADM designs that deliver space, power consumption and operational cost savings as well as systems advantages.

Wavelength-selective switch

A WSS takes wavelength-division multiplexed (WDM) channels from an input fibre and distributes them as required across an array of output fibres. Typical WSS configurations include a 1x9 - a one input fibre port and nine output ports - and a 1x20.

Current WSS designs comprise a diffraction grating, a cylindrical lens and an LCOS panel that is used to deflect the light channels to the required output fibres.

The diffraction grating separates the WDM channels while the cylindrical lens produces an elongated projection of the channels onto the LCOS device. The panel’s liquid crystals are oriented in such a way to direct the projected light channels to the appropriate output fibres. The orientation of the arrays of liquid crystals that perform the various steerings are holograms.

Commercial WSSes use the LCOS panel to steer in one dimension only: left or right. This means the output fibres are arranged in an array and the number of fibres is limited by the total deflection the LCOS can achieve. ROADMap Systems has developed a technique that produces holograms on the LCOS panel that steer light in two dimensions: left and right, up and down and diagonally.

Moreover, the holograms are confined to a small area of the panel, far fewer pixels than the elongated beams of a 1D WSS. Such confinement allows multiple light beams to be steered to the output fibre bundles.

“You use a much smaller area of the LCOS to bend things in 2D,” says Karl Heeks, CEO at ROADMap Systems.

Platform demonstrator

ROADMap System’s key intellectual property is its know-how to create the steering pattern - the hologram - programmed onto the LCOS panel.

The 2D WSS system requires calibration to create the precision holograms. The calibration data is generated during the device’s manufacture and forms the input to an algorithm that creates the holograms needed for the LCOS to steer accurately the traffic to the output fibres.

You use a much smaller area of the LCOS to bend things in 2D

ROADMap Systems has demonstrated its 2D steering technology to service providers, system vendors and optical subsystem players.

Now, the company is working to build the 24, 1x12 WSSs on an optical bench which it expects to complete by the year-end. The start-up is also creating the calibration software used for 2D beam steering as well as a user interface to allow networking staff to set up their required connections.

The first pre-production packaged systems – each one comprising a 4K LCOS panel and 312 fibres - are expected for delivery for trialling in 2019. The start-up is reluctant to give a firm date as it is still exploring design options. For example, ROADMap Systems has an improved lower-loss, more compact fibre coupling design but it has yet to decide whether to incorporate it or its existing design for its platform.

“We are not intending the prototype to go into a system within the network,” says Heeks. “It is more a vehicle to illustrate its capabilities.”

System benefits

The main benefit of ROADMap Systems’ 2D beam-steering WSS architecture is not so much its optical performance; the start-up expects its design to match the optical performance of existing 1D WSSes. Rather, there are architectural benefits besides the obvious integration and cost benefits of putting 24 WSSes in one platform.

The first system advantage is the ability to use the many WSSes to implement ROADMs of several degrees including the ROADM’s add-drop architecture. A two-degree ROADM handles east and west fibre pairs while a three-degree ROADM adds north-facing traffic as well.

A ROADM architecture using 1xN splitters as part of the multicast switch. Source: ROADMap Systems.

A ROADM architecture using 1xN splitters as part of the multicast switch. Source: ROADMap Systems.

To add and drop light-paths, a multicast switch is used (shown in green in the diagram above). The multicast switch can be implemented using optical splitters, however, due to their loss, optical amplifiers are needed to boost the signals, adding to the overall cost and system complexity.

WSSes can be used instead of the splitters as part of the multicast switch architecture such that optical amplification is not needed; the optical loss the WSS stage adds being much lower than the splitters. Removing optical amplification impacts significantly the overall ROADM cost (see diagram below).

A ROADM architecture using 1xN WSSes as part of the multicast switch. Source: ROADMap Systems.

A ROADM architecture using 1xN WSSes as part of the multicast switch. Source: ROADMap Systems.

The integrated platform’s large number of WSSes will ease the implementation of the latest generation of ROADMs that are colourless, directionless and contentionless.

A colourless ROADM decouples the wavelength-dependency such that a light-path can be used on any of the network interface ports. Directionless refers to having full flexibility in the routeing of a light-path to any of the ports. Lastly, contentionless means non-blocking, where the same wavelength channel can be accommodated across all the degrees of the ROADM without contention.

And being LCOS-based, ROADMap’s WSSes also support a flexible grid enabling the ROADM to support channels such as coherent transmissions above 200 gigabit-per-second that do not conform to the rigid 50GHz-wide ITU grid spacings.

The second system advantage of the platform is that with its many WSSes, it can route and add-drop wavelengths across both the C and L-bands. However, the company is not planning to implement this feature in its preproduction prototype.

Next steps

ROADMap Systems says it is focussed on producing and testing its pre-production prototype. A further round of investment will be needed to turn the design into a commercial product.

“We believe that such a highly-integrated architecture will offer immediate performance and economic benefits to many teleccom applications,” says Heeks. “It is also well positioned for datacentre – DCI - applications where data needs to be routed between distributed datacentres linked by parallel fibres."

ECOC 2013 review - Part 2

- Oclaro's Raman and hybrid amplifier platform for new networks

- MxN wavelength-selective switch from JDSU

- 200 Gigabit multi-vendor coherent demonstration

- Tunable SFP+ designs proliferate

- Finisar extends 40 Gigabit QSFP+ to 40km

- Oclaro’s tackles wireless backhaul with 2km SFP+ module

Finisar's 40km 40 Gig QSFP+ demo. Source: Finisar

Finisar's 40km 40 Gig QSFP+ demo. Source: Finisar

Amplifier market heats up

Oclaro detailed its high performance Raman and hybrid Raman/ Erbium-doped fibre amplifier platform. "The need for this platform is the high-capacity, high channel rates being installed [by operators] and the desire to be scalable - to support 400 Gig and Terabit super-channels in future," says Per Hansen, vice president of product marketing, optical networks solutions at Oclaro.

"Amplifiers are 'hot' again," says Daryl Inniss, vice president and practice leader components at market research firm, Ovum. For the last decade, amplifier vendors have been tasked with reducing the cost of their amplifier designs. "Now there is a need for new solutions that are more expensive," says Inniss. "It is no longer just cost-cutting."

Amplifiers are used in the network backbone to boost the optical signal-to-noise ratio (OSNR). Raman amplification provides significant noise improvement but it is not power efficient so a Raman amplifier is nearly always matched with an Erbium one. "You can think of the Raman as often working as a pre-amp, and the Erbium-doped fibre as the booster stage of the hybrid amplifier," says Hansen. System houses have different amplifier approaches and how they connect them in the field, while others build them on one card, but Raman/ Erbium-doped fibre are almost always used in tandem, says Hansen.

Oclaro provides Raman units and hybrid units that combine Raman with Erbium-doped fibre. "We can deliver both as a super-module that vendors integrate on their line cards or we can build the whole line card for them" says Hansen.

The Raman amplifier market is way bigger than people have forecast

Since Raman launches a lot of pump power into the fibre, it is vital to have low-loss connections that avoid attenuating the gain. "Raman is a little more sensitive to the quality of the connections and the fibre," says Hansen. Oclaro offers scan diagnostic features that characterise the fibre and determine whether it is safe to turn up the amplification.

"It can analyse the fibre and depending on how much customers want us to do, we can take this to the point that it [the design] can tell you what fibre it is and optimise the pump situation for the fibre," says Hansen. In other cases, the system vendors adopt their own amplifier control.

Oclaro says it is in discussion with customers about implementations. "We are shipping the first products based on this platform," says Hansen.

"[The] Raman [amplifier market] is way bigger than people have forecast," says Inniss. This is due to operators building long distance networks that are scalable to higher data rates. "Coherent transmission is the focal point here, as coherent provides the mechanism to go long distance at high data rates," says Ovum analyst, Inniss.

Wavelength-selective switches

JDSU discussed its wavelength-selective switch (WSS) products at ECOC. The company has previously detailed its twin 1x20 port WSS, which has moved from development to volume production.

At ECOC, JDSU detailed its work on a twin MxN WSS design. "It is a WSS that instead of being a 1xN - 1x20 or a 1x9 - it is an MxN," says Brandon Collings, chief technology officer, communications and commercial optical products at JDSU. "So it has multiple input and output ports on both sides." Such a design is used for the add and drop multiplexer for colourless and directionless reconfigurable optical add/ drop multiplexers (ROADMs).

"People have been able to build colourless and directionless architectures using conventional 1xN WSSes," says Collings. The MxN serves the same functionality but in a single integrated unit, halving the volume and cost for colourless and directionless compared to the current approach.

JDSU says it is also completing the development of a twin multicast switch, the add and drop multiplexer suited to colourless, directionless and contentionless ROADM designs.

200 Gigabit coherent demonstration

ClariPhy Communications, working with NeoPhotonics, Fujitsu Optical Components, u2t Photonics and Inphi, showcased a reference-design demonstration of 200 Gig coherent optical transmission using 16 quadrature amplitude modulation (16-QAM).

For the demonstration, ClariPhy provided the coherent silicon: the digital-to-analogue converter for transmission and the receiver analogue-to digital and digital signal processing (DSP) used to counter channel transmission impairments. NeoPhotonics provided the lasers, for transmission and at the receiver, u2t Photonics supplied the integrated coherent receiver, Fujistu Optical Components the lithium niobate nested modulator while Inphi provided the quad-modulator driver IC.

ClariPhy is developing a 28nm CMOS Lightspeed chip suited for metro and long-haul coherent transmission. The chip will support 100 and 200 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) data rates and have an adjustable power consumption tailored to the application. The chip will also be suited for use within a coherent CFP module.

"All the components that we are talking about for 100 Gig are either ready or will soon be ready for 200 and 400 Gig," says Ferris Lipscomb, vice president of marketing at NeoPhotonics. To achieve 400Gbps, two 16-QAM channels can be used.

The DWDM market for 10 Gig is now starting to plateau

Tunable SFPs

JDSU first released a 10Gbps SFP+ optical module tunable across the C-band in 2012, a design that dissipates up to 2W. The SFP+ MSA agreement, however, calls for no greater than a 1.5W power consumption. "Our customers had to deal with that higher power dissipation which, in a lot of cases, was doable," says JDSU Collings.

Robert Blum, Oclaro

Robert Blum, Oclaro

JDSU's latest tunable SFP+ design now meets the 1.5W power specification. "This gets into the MSA standard's power dissipation envelop and can now go into every SFP+ socket that is deployed," says Collings. To achieve the power target involved a redesign of the tunable laser. The tunable SFP+ is now sampling and will be generally available one or two quarters hence.

Oclaro and Finisar also unveiled tunable SFP+ modules at ECOC 2013. "The design is using the integrated tunable laser and Mach-Zehnder modulator, all on the same chip," says Robert Blum, director of product marketing for Oclaro's photonic components.

Neither Oclaro nor Finisar detailed their SFP+'s power consumption. "The 1.5W is the standard people are trying to achieve and we are quite close to that," says Blum.

Both Oclaro's and Finisar's tunable SFP+ designs are sampling now.

Reducing a 10Gbps tunable transceiver to a SFP+ in effect is the end destination on the module roadmap. "The DWDM market for 10 Gig is now starting to plateau," says Rafik Ward, vice president of marketing at Finisar. "From an industry perspective, you will see more and more effort on higher data rates in future."

40G QSFP+ with a 40km reach

Finisar demonstrated a 40Gbps QSFP+ with a reach of 40km. "The QSFP has embedded itself as the form-factor of choice at 40 Gig," says Ward.

Until now there has been the 850nm 40GBASE-SR4 with a 100m reach and the 1310nm 40GBASE-LR4 at 10km. To achieve a 40km QSFP+, Finisar is using four uncooled distributed feedback (DFB) lasers and an avalanche photo-detector (APD) operating using coarse WDM (CWDM) wavelengths spaced around 1310nm. The QSFP+ is being used on client side cards for enterprise and telecom equipment, says Finisar.

Module for wireless backhaul

Oclaro announced an SFP+ that supports the wireless Common Public Radio Interface (CPRI) and Open Base Station Architecture Initiative (OBSAI) standards used to link equipment in a wireless cell's tower and the base station controller.

Until now, optical modules for CPRI have been the 10km 10GBASE-LR4 modules. "You have a relatively expensive device for the last mile which is the most cost sensitive [part of the network]," says Oclaro's Hansen.

Oclaro's 1W SFP+ reduces module cost by using a simpler Fabry-Perot laser but at the expense of a 2km reach only. However, this is sufficient for a majority of requirements, says Hansen. The SFP supports 2.5G, 3Gbps, 6Gbps and 10Gbps rates. "CPRI has been used mostly at 3 Gig and 6 Gig but there is interest in 10 Gig due to growing mobile data traffic and the adoption of LTE," says Hansen.

The SFP+ module is sampling and will be in volume production by year end.

For Part 1, click here

100 Gigabit 'unstoppable'

A Q&A with Andrew Schmitt (@aschmitt), directing analyst for optical at Infonetics Research.

"40Gbps has even less value in the metro than in the core"

Andrew Schmitt, Infonetics Research

A study from market research firm, Infonetics Research, has found that operators have a strong preference for deploying 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) technology as they upgrade their networks.

Infonetics interviewed 21 incumbent service providers, competitive operators and mobile operators that have either 40Gbps, 100Gbps or both wavelength types installed in their networks, or that plan to install by next year (2013).

The operators surveyed, from all the major regions, account for over a quarter (28%) of worldwide telecom carrier revenue and capital expenditure.

The study's findings include:

- A strong preference by the carriers for 100Gbps transport in both Brownfield and Greenfield installations. Carriers will use 40 and 100Gbps to the same degree in existing Brownfield networks while favouring 100Gbps for new, Greenfield builds.

- The reasons to deploy 40Gbps and 100Gbps optical transport equipment include lowering the cost per bit, taking advantage of the superior dispersion performance of coherent optics, and lowering incremental common equipment costs due to the increased spectral efficiency.

- Most respondents indicate 40Gbps is only a short-term solution and will move the majority of installations to 100Gbps once those products become widely available.

- Non-coherent 100Gbps is not yet viewed as an important technology.

- Colourless and directionless ROADMs and Optical Transport Network (OTN) switching are important components of Greenfield builds; gridless and contentionless ROADMs are much less so.

Q&A with Andrew Schmitt

Q. A key finding is that 40Gbps and 100Gbps are equally favoured for Brownfield routes. And is it correct that Brownfield refers to existing routes carrying 10Gbps and maybe 40Gbps wavelengths while Greenfield involves new 100Gbps wavelengths? What is it about Brownfield that 40Gbps and 100Gbps have equal footing? Equally, for Greenfield, is the thinking: "If we are deploying a new lit fibre, we might as well start with the newest and fastest"?

A: The assumptions on Brownfield versus Greenfield are correct, the definitions in the survey and the report are more detailed but that is right.

It is more an issue that they [carriers] are building with 40Gbps now but will transition to 100Gbps where it can be used. Where it can't be used they stick with 40Gbps. There are many reasons why 100Gbps may not work in existing networks.

Q: Another finding is that 40Gbps is seen as a short-term solution. What is short term? And will that also be true for the metro or does metro have its own dynamic?

A: We didn't test timing explicitly for Greenfield versus Brownfield networks. It [40Gbps] doesn't necessarily peak, it is just not growing at the same rate as 100Gbps. And 40Gbps has even less value in the metro than in the core, particularly in Greenfield builds. With Greenfield 100Gbps combined with soft-decision forward error correction (SD-FEC), it is almost as good as 40Gbps.

Q: The study found that non-coherent 100Gbps isn't yet viewed as an important technology. Why do you think that is so? And what is your take on the non-coherent 100Gbps opportunity?

A: The jury is still out.

The large customers I spoke with haven't looked at it and therefore can't form an opinion. A lot of promises and marketing at this point but that doesn't mean it won't work. Module vendors are pretty excited about it and they aren't stupid.

Q: You say colourless and directionless is seen as important ROADM attributes, gridless and contentionless much less so. If operators are building 100Gbps Greenfield overlays, is not gridless a must to future-proof the network investment?

A: The gridless requirement is completely overblown and folks positioning it as a requirement today haven't done the work to understand the issues trying to use it today. This survey was even more negative than I expected.

ROADMs: core role, modest return for component players

Next-generation reconfigurable optical add/ drop multiplexers (ROADMs) will perform an important role in simplifying network operation but optical component vendors making the core component - the wavelength-selective switch (WSS) - on which such ROADMs will be based should expect a limited return for their efforts.

"[Component suppliers] are going to be under extreme constraints on pricing and cost"

"[Component suppliers] are going to be under extreme constraints on pricing and cost"

Sterling Perrin, Heavy Reading

That is one finding from an upcoming report by market research firm, Heavy Reading, entitled: "The Next-Gen ROADM Opportunity: Forecast & Analysis".

"We do see a growth opportunity [for optical component vendors]," says Sterling Perrin, senior analyst and author of the report. “But in terms of massive pools of money becoming available, it's not going to happen; it is a modest growth in spend that will go to next-generation ROADMs."

That is because operators’ capex spending on optical will grow only in single digits annually while system vendors that supply the next-generation ROADMs will compete fiercely, including using discounting, to win this business. "All of this comes crashing down on the component suppliers, such that they are going to be under extreme constraints on pricing and cost," says Perrin. The report will quantify the market opportunity but Heavy Reading will not discuss numbers until the report is published.

Next-generation ROADMs incorporate such features as colourless (wavelength-independence on an input port), directionless (wavelength routing to any port), contentionless (more than one same-wavelength light path accommodated at a port) and flexible spectrum (variable channel width for signal rates above 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps)).

Networks using such ROADMs promise to reduce service providers' operational costs. And coupled with the wide deployment of coherent optical transmission technology, next-generation ROADMs are set to finally deliver agile optical networks.

Other of the report’s findings include the fact that operators have been deploying colourless and directionless ROADMs since 2010, even though implementing such features using current 1x9 WSSs are cumbersome and expensive. However, operators wanting these features in their networks have built such systems with existing components. "Probably about 10% of the market was using colourless and directionless functions in 2010," says Perrin.

Service providers are requiring ROADMs to support flexible spectrum even though networks will likely adopt light paths faster than 100Gbps (400Gbps and beyond) in several years' time.

The need to implement a flexible spectrum scheme will force optical component vendors with microelectromechanical system (MEMS) technology to adopt liquid crystal technology – and liquid-crystal-on-silicon (LCoS) in particular - for their WSSs (see Comments). "MEMS WSS technology is great for all the stuff we do today - colourless, directionless and contentionless - but when you move to flexible spectrum it is not capable of doing that function," says Perrin. "The technology they (vendors with MEMS technology) have set their sights on - and which there is pretty much agreement as the right technology for flexible spectrum - is the liquid crystal on silicon." A shift from MEMS to LCoS for next-generation ROADM technology is thus to be expected, he says.

Perrin also highlights how coherent detection technology, now being installed for 100 Gbps optical transmission, can also implement a colourless ROADM by making use of the tunable nature of the coherent receiver. "It knocks out a bunch of WSSs added to the add/ drop," says Perrin. "It is giving a colourless function for free, which is a huge advantage."

Perrin views next-gen ROADMs as a money-saving exercise for the operators, not a money-making one. "This is hitting on the capex as well as the opex piece which is absolutely critical," he says. "You see the charts of the hockey stick of bandwidth growth and flat venue growth; that is what ROADMS hit at."

The Heavy Reading report will be published later this month.

Further reading:

Capella: Why the ROADM market is a good place to be

The reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexer (ROADM) market has been the best performing segment of the optical networking market over the last year. According to Infonetics Research, ROADM-based wavelength division multiplexing (WDM) equipment grew 20% from Q2, 2010 to Q1, 2011 whereas the overall optical networking market grew 7%.

“It’s the Moore’s Law: Every two years we are doubling the capacity in terms of channel count and port count”

Larry Schwerin, Capella

The ROADM market has since slowed down but Larry Schwerin, CEO of wavelength-selective-switch (WSS) provider, Capella Intelligent Subsystems, says the market prospects for ROADMs remain solid.

Capella makes WSS products that steer and monitor light at network nodes, while the company’s core intellectual property is closed-loop control. Its WSS products are compact, athermal designs based on MEMS technology that switch and monitor light.

Schwerin compares Capella to a plumbing company: “We clean out pipes and those pipes happen to be fibre-optics ones.” The reason such pipes need ‘cleaning’ – to be made more efficient - is because of the content they carry. “It is bandwidth demand and the nature of the bandwidth which has changed dramatically, that is the fundamental driver here,” says Schwerin.

Increasingly the content is high-bandwidth video and streamed to end-user devices no longer confined to the home, while the video requested is increasingly user-specific. Such changes in the nature of content are affecting the operators’ distribution networks.

“Using Verizon as an example, they are now pushing 50 wavelengths per fibre in the metro,” says Schwerin. Such broad lanes of traffic arrive at network congestion points where certain fibre is partially used while other fibre is heavily used. “What they [operators] need is a vehicle that allows them to dynamically and remotely reassign those wavelengths on-the-fly,” says Schwerin. “That is what the ROADM does.”

Capella attributes strong ROADM sales to a maturing of the technology coupled with a price reduction. The technology also brings valuable flexibility at the optical layer. “It [ROADM] extends the life of the existing infrastructure, avoiding the need for capital to put new fibre in - which is the last thing the operators want to do,” says Schwerin.

$20M funding

Capella raised US $20M in April as part of its latest funding round. The funding is being used for capital expansion and R&D. “We are working on new engine technology, new patentable concepts,” says Schwerin. “We were at Verizon a few weeks ago doing a world-first demo which we will be putting out as a press release.” For now the company will say that the demonstration is research-oriented and will not be implemented within ROADM systems anytime soon.

“You have to be competitive in this market, that is the downfall of our sector. People getting 30 or 40% gross margins and calling that a win – that is not a win - that is why this sector is in trouble”

One investor in the latest funding round is SingTel Innov8, the investment arm of the operator SingTel. Schwerin says it has no specific venture with the operator but that SingTel will gain insight regarding switching technologies due to the investment. “We will sit down with them and talk about their plans for network evolution and what is technologically possible,” says Schwerin, who points out that many of the carriers have lost contact with technologies since they shed their own large, in-house R&D arms.

Cappella offers two 1x9 WSS products and by the end of this year will also offer a 1x20 product. “It’s the Moore’s Law: Every two years we are doubling the capacity in terms of channel count and port count,” says Schwerin.

“We have a reasonable share of design wins shipping in volume - we have thousands of switches deployed throughout the world,” says Schwerin. “We are not of the size of a JDSU or a Finisar but our objective within the next 18 months is to capture enough market share that you would see us as a main supplier of that ilk.”

The CEO stresses that Capella’s presence a decade after the optical boom ended proves it is offering distinctive products. “Our whole business model is about innovation and differentiation,” says Schwerin.

But as a start-up how can Capella compete with a JDSU or a Finisar? “I have these conversations with the carriers: if all they are doing is looking for second or third sourcing of commodity product parts then there is no room for a company like a Capella.”

The key is taking a dumb switch and turning it into a complete wavelength managed solution that can be easily added within the network.

Schwerin also stresses the importance of ROADM specsmanship: wider lightpath channel passbands, lower insertion loss, smaller size, lower power consumption and competitive pricing: “You have to be competitive in this market, that is the downfall of our sector,” says Schwerin. “People getting 30 or 40% gross margins and calling that a win – that is not a win - that is why this sector is in trouble.”

Advanced ROADM features

There has been much discussion in the last year regarding the four advanced attributes being added to ROADM designs: colourless, directionless, contentionless and gridless or CDCG for short.

Interviewing six system vendors late last year, while all claimed they could support CDCG features, views varied as to what would be needed and by when. Meanwhile all the system vendors were being cautious until it was clearer as to what operators needed.

Schwerin says that what the operators really want is a ‘touchless’ ROADM. Capella says its platform is capable of supporting each of the four attributes and that the company has plans for implementing each one. “Just because the carriers say they want it, that doesn’t mean that they are willing to pay for it,” says Schwerin. “And given the intense pricing pressure our system friends are in, they are rightly being cautious.”

Capella says that talking to the carriers doesn’t necessarily answer the issue since views vary as to what is needed. “The one [attribute] that seems clearest of all is colourless,” says Schwerin. And colourless is served using higher-port-count WSSs.

The directionless attribute is more a question of implementation and the good news is that it requires more WSSs, says Schwerin. Contentionless addresses the issue of wavelength blocking and is the most vague, a requirement that has even “faded away a bit”. As for gridless, that may be furthest out as it has ramifications in the network.

Schwerin says that Capella is seeing requests for reduced WSS switching times as well as wavelength tracking, tagging a wavelength whose signature can be identified optically and which is useful for network restoration and when wavelengths are passed between carriers’ networks.

Roadmap

In terms of product plans, Capella will launch a 1x20 WSS product later this year. The next logical step in the development of WSS technology is moving to a solid-state-based design.

“All of the the technologies out there today– liquid crystal, MEMS, liquid-crystal-on-silicon - are all free space [designs],” says Schwerin. “We have a solid-state engine in the middle [of our WSS] and we are down to five photonic-integrated-circuit components so the obvious next stage is silicon photonics.”

Does that mean a waveguide-based design? “Something of that form – it may not be a waveguide solution but something akin to that - but the idea is to get it down to a chip,” says Schwerin. “We are not pure silicon photonics but we are heading that way.”

Such a compact chip-based WSS design is probably five years out, concludes Schwerin.

Further information:

A Fujitsu ROADM discussion with Verizon and Capella – a Youtube 30-min video

To efficiency and beyond

Part 3: ROADM and control plane developments

ROADMs and control plane technology look set to finally deliver reconfigurable optical networks but challenges remain.

Operators are assessing how best to architect their networks - from the router to the optical layer - to boost efficiencies and reduce costs. It is developments at the photonic layer that promise to make the most telling contribution to lowering the cost of transport, a necessity given how the revenue-per-bit that carriers receive continues to dwindle.

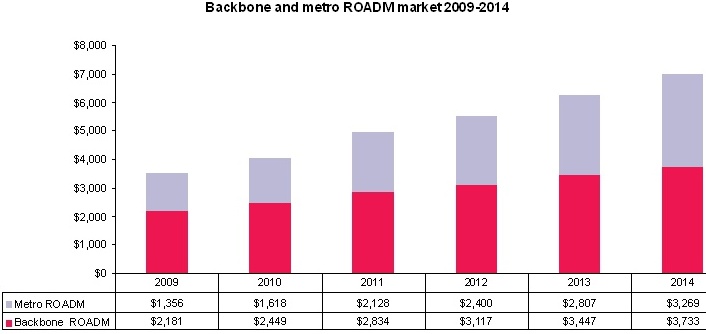

Global ROADM forecast 2009 -14 in US $ miliions Source: Ovum

Global ROADM forecast 2009 -14 in US $ miliions Source: Ovum

“The challenge of most service providers largely hasn’t changed for some time: dealing with growth in demand economically,” says Drew Perkins, CTO of Infinera. “How can operators grow the capacity on each route and switch it, largely on a packet-by-packet basis, without increasing the numbers of dollars going into the network.”

Until now, dynamic optical networking has been conducted at the electrical layer. Electrical switches set up connections within a second, support shared mesh restoration in under 100 milliseconds (ms), and have a proven control plane that oversees networks up to 1,000 networking nodes. This is the baseline performance that a photonic layer scheme will be compared to, says Joe Berthold, vice president of network architecture at Ciena.

AT&T’s Optical Mesh is one such electrically-enable service. Using Ciena’s CoreDirector electrical switches, customers can change their access circuits in SONET STS-1 (50 Megabits-per-second) increments via a web interface. AT&T wants to expand further the capacity increments it places in customers’ hands.

“The real problem with operators today is that it takes way too long to set up a new connection with existing optical infrastructure.”

Tom McDermott, Fujitsu Network Communications

Developments at the photonic layer such as advances in reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexers (ROADMs) as well as control plane and management software complement the electrical layer control. ROADMs enable the redirection of large bandwidths while the electrical layer, with its sub-wavelength grroming and switching at the packet level, accommodates more rapid traffic changes. Operators will benefit as the two layers are used more efficiently.

“The photonic layer is the cheapest per bit per function, cheaper than the transport layer – OTN (Optical Transport Network) or the SONET layer – and the packet layer,” says Brandon Collings, CTO of JDS Uniphase’s consumer and commercial optical products division. “The more efficient, functional and powerful the control plane, the better off operators will be.”

ROADM evolution

ROADMs sit at the core of the network and largely define its properties. “The network’s wavelengths may be 10, 40 or 100 Gig; that is just bolting something on the edge. The ROADM sits in the middle, it’s there, and it has to handle whatever you throw at it,” says Simon Poole, director new business ventures at Finisar.

Operators have gone from using fixed optical add-drop multiplexers (OADMs) to ROADMs with fixed add-drop ports to now colourless and directionless ROADMs. Each step increases the flexibility of the switching devices while reducing the manual intervention required when setting up new lightpaths.

“There has been a much greater drive in the US [for ROADMs] but it is now picking up in Europe”

“There has been a much greater drive in the US [for ROADMs] but it is now picking up in Europe”

Ulf Persson, Transmode Systems

Network architectures also reflect these advances. First ROADMs were typically two-dimensional nodes that enabled metro rings. Now optical mesh networks are possible using the ROADMs’ greater number of interfaces, or degrees.

Transmode Systems has many of its customers – smaller tier one and tier two operators - in Europe, and focusses on the access, metro and metro-regional markets.

“It is not just the type and size of the operators, there are also regional differences in how all-optical and ROADMs are used,” says Ulf Persson, director of network architecture at Transmode. “There has been a much greater drive in the US [for ROADMs] but it is now picking up in Europe.” One reason for limited ROADM demand in Europe, says Persson, is that for smaller networks it is easier to design and predict growth.

Operators with fixed OADMs must plan their networks carefully. When provisioning a service, engineers have to visit and reconfigure the nodes needed to support the new route. In contrast, with fixed add-drop port ROADMs, engineers only need visit the end points.

The end points require manual intervention since the ROADM restricts the lightpath’s direction and wavelength. ROADMs at nodes along the route can at least change the direction but not the lightpath’s wavelength. “You can do the express routing efficiently, it is the [ROADM] drop side that that is not automated at this point,” says Poole.

This still benefits operators even if it doesn’t meet all their optical layer requirements. “Where ROADMs have helped is that while service technicians must visit the end points - connecting the transponder card and client equipment - they save on the intermediate site visits,” says Jörg-Peter Elbers, vice president, advanced technology at ADVA Optical Networking. “Just by a mouse click, you can set up all the nodes in the right configurations without the hassle of doing this manually.”

The result is largely static networks that once set up are seldom changed. “The real problem with operators today is that it takes way too long to set up a new connection with existing optical infrastructure,” says Tom McDermott, distinguished strategic planner, Fujitsu Network Communications.

Colourless and directionless ROADMs aim to solve this. A tunable transponder can now be pointed to any of the ROADM’s network interfaces while exploiting its tunability for the lightpath’s wavelength or colour.

The ROADM percentage of the total metro WDM market. The market comprises Coarse WDM, fixed and reconfigurable OADMs. Source: Ovum

The ROADM percentage of the total metro WDM market. The market comprises Coarse WDM, fixed and reconfigurable OADMs. Source: Ovum

Such colourless and directionless ROADMs offer several benefits. An operator can have several transponders ready for provisioning to meet new service demand. This arrangement for ‘deployment velocity’ has yet to take hold since operators are reluctant to have costly transponders idle, especially if they are 40 and 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) ones.

Colourless and directionless ROADMs will more likely be used for network restoration during maintenance or a fibre cut. This is slow restoration, nowhere near the 100ms associated with electrical signalling; optical signals are analogue and each lightpath must be turned up carefully. “When you re-route an optical signal going more than 1,000km, taking it off one route affects all the other signals on that route and they need to be rebalanced; then putting it on another route, they too need to be rebalanced,” says Infinera’s Perkins. “It is very difficult to manage.”

ADVA Optical Networks cites the example of operators using 1+1 route protection. When one route is down for maintenance, the remaining route is left unprotected. Colourless and directionless ROADMs can be used to set up a spare route during the maintenance. In developing countries, where fibre cuts are more common, 1+N protection can provide operators with redundancy to survive multiple failures. Such a restoration strategy is especially needed if getting to a fault in remote area may take days.

The extra flexibility of the newer ROADMs provide will also aid operators with load balancing, moving traffic away from hotspots as the network grows.

WSSs at the core

The building block at the core of the ROADM is the wavelength-selective switch (WSS). Such switch building-blocks are implemented using light-switching technologies such as liquid crystal, liquid crystal on silicon and MEMS. The WSS routes a lightpath to a particular fibre, with the WSS’s degree in several configurations: 1x2, 1x4, 1x9 and, under development, a 1x23. The ROADM’s degree relates to the network interfaces it supports - a 2-degree ROADM supports two fibre pairs, pointing east and west. A WSS is used for each ROADM degree and hence with each fibre pair.

A 1:9 WSS supports an 8-degree ROADM with the remaining two ports used for local multiplexing and demultiplexing. So far, eight fibre pairs have been sufficient. A 1:23 WSS is being developed to support yet more degrees at a node. For example, more than one fibre pair can be sent in the same direction (doubling a route’s capacity) and for adding extra add-drop banks. JDS Uniphase is one vendor developing a 1:23 WSS.

"Where I’m seeing first interest beyond 1x9 is business service or edge applications - where at a given node point operators need a lot of attachments to different enterprise networks at high capacity multi-wavelength levels,” says Tom Rarick, principal engineer, transport, at Tellabs. “Within infrastructure applications, a 1x9 provides the degree of fibre connectivity necessary; I rarely see beyond a 1x6.”

“The next big thing [after colourless and directionless] is what people call contentionless and gridless, adding yet more flexibility to the optical infrastructure.”

“The next big thing [after colourless and directionless] is what people call contentionless and gridless, adding yet more flexibility to the optical infrastructure.”

Jörg-Peter Elbers, ADVA Optical Networking

For a WSS, the common port connects to the outbound fibre of any given direction, whereas the 9 ports [for a 1:9] face inwards to the centre of the node, says JDSU’s Collings (click here for a JDSU presentation). He describes the WSS as a gatekeeper that determine which lightpaths from which fibres leave a node. As for the incoming fibre, the lightpaths carried are sent to each of the other ROADM node WSSs, one for each direction. “Each WSS selects which channel from which port leaves the node,” says Collings.

To make a ROADM colourless and directionless, extra add-drop ports hardware must be added. These route lightpaths to any node and on any wavelength, or drop any lightpath from any of the other nodes. The add-drop node is built using further WSSs.

One issue still to be resolved is whether WSS sub-system vendors provide all the elements that are added to the WSS to make the ROADM colourless and directionless. “It is not clear whether we should be developing the whole thing or providing the modules for the customers’ line cards and systems,” says Poole.

“The next big thing [after colourless and directionless] is what people call contentionless and gridless, adding yet more flexibility to the optical infrastructure,” says Elbers.(Click here for an ADVA Optical Networking ROADM presentation)

Contentionless refers to avoiding same-wavelength contention. With a colourless and directional ROADM, only one copy of a particular wavelength can be dropped. “With a four-degree node you can have a 96-channel fibre on each,” says Krishna Bala, executive vice president, WSS division at Oclaro. “You may want to drop at the node lambda1 from the east and the same lambda1 coming from the west.” To drop the two, same wavelengths, an extra add-drop block is required.

To make the ROADM fully contentionless, as many add-drop blocks as ROADM degrees are needed. This requires more WSSs, or alternatively 1:N splitters, as well as N:1 selection switches. This way any of the dropped wavelengths from any of the incoming fibres can be routed to any one of the add-drop’s transponders.

“The building blocks for colourless and directionless ROADMs are there; we sell them as a product,” says Elbers, who stresses that the cost of the WSS building block is coming down. But the question remains whether an operator values such network functionality sufficiently to pay. “Without naming names, big carriers are looking at these – they want to have a future-proof, simple-to-plan network,” says Elders.

“It is strictly economics,” agrees Ciena’s Berthold. “We’ve offered a colourless-directionless ROADM for some time. Some buy that but more often they are going for lower cost.”

Gridless

A further ROADM attribute being added to the WSS is gridless even though it will be several years before it is needed. WSS vendors are keen to add the feature – adaptive channel widths - now so that operators’ ROADM deployments will be future-proofed.

“They [WSS vendors] have got to be in a tough spot. They have to invest all that [R&D] money while they [carriers/ system vendors] ask for the world.”

“They [WSS vendors] have got to be in a tough spot. They have to invest all that [R&D] money while they [carriers/ system vendors] ask for the world.”

Ron Kline, Ovum.

Channel bandwidths wider than 50GHz will be needed for line speeds above 100Gbps. Gridless refers to the ability to accommodate lightpaths that do not just fit on the International Telecommunication Union’s (ITU) 50 or 100GHz grid. WSS makers are developing fine pass-band filters that when combined in integer increments form variable channel widths.

“There is a great deal of concern from operators about how they can efficiently use the spectrum to maximize fibre capacity,” says Poole. What operators want is the ability to generate channel bandwidth with much finer granularity and to move away from fixed channel widths.

According to Poole, NTT have demonstrated a ROADM with 12.5GHz increments, others are thinking 25GHz or even 37.5GHz. Finisar says this issue has gained much operator attention in the last six months and that there is urgency for WSS vendors to implement gridless so that any ROADM deployed will be able to support future transmission rates beyond 100Gbps.

“They [WSS vendors] have got to be in a tough spot,” says Ron Kline, principal analyst for network infrastructure at Ovum. “They have to invest all that [R&D] money while they [carriers/ system vendors] ask for the world.”

Coherent receiver technology used for 100Gbps optical transmission will also help enable dynamic optical networking by overcoming technical issues when rerouting paths.

Optical signal distortion in the form of chromatic dispersion and polarisation mode dispersion (PMD) are so much worse at 40Gbps and 100Gbps. Even on 10Gbps routes, where tolerance to dispersion is greater, compensation can be an issue when redirecting a lightpath during network restoration. That is because the alternative route is likely to be longer. Unless the dispersion compensation is correct, there is uncertainty as to whether the alternative link will work, says Ciena’s Berthold.

“With a coherent receiver, you are now independent of dispersion since you can adaptively compensate for dispersion using the [receiver’s] DSP ASIC,” says Berthold. “You no longer have to worry is you have it [the compensation tuning] just right.”

The ASIC can also deliver real-time latency, chromatic dispersion and PMD network measurements at path set-up. This avoids first testing the link, and possible errors when entering measurements in the planning-path network set-up tools. “Coherent technology for 40 Gig and 100 Gig is potentially a game changer in making ROADMs work,” says Berthold.

Coherent digital transponders at 40 and 100Gbps will also drive the deployment of more advanced ROADMs, argues Oclaro. “The need to extract value from the bank of [40 and 100G coherent] transponders in a colourless-directionless sense becomes a lot more important,” says Peter Wigley, director, marketing and technology strategy at Oclaro.

Control plane

Tunable lasers, flexible ROADMS and even coherent technology may be prerequisites for agile optical networks, but another key component is the control plane software. “Many of the networks today have some of the hardware components to make them agile but lack the software,” says Andrew Schmitt, directing analyst, optical, at Infonetics Research. (See ROADM Q&A with Andrew Schmitt.)

The network can be split into the data plane, used to transport traffic, the control plane that uses routing and signalling protocols to set up connections between nodes, and the management plane that oversees the control plane.

The network can be split into the data plane, used to transport traffic, the control plane that uses routing and signalling protocols to set up connections between nodes, and the management plane that oversees the control plane.

“What is deployed mostly today is a SONET/SDH control plane,” says Tellabs’ Rarick. “This is to manage SONET/SDH ring or mesh networks, using standalone cross-connects or partnered with ROADMs, with the switching primarily done electrically.”

Three industry bodies are advancing control plane technology in several areas including the optical level.

The Internet Engineering Task Force (IEFT) is standardising Generalized Multiprotocol Label Switching (GMPLS) while the ITU is developing control plane requirements and architecture dubbed Automatically Switched Optical Networks (ASON). The third body, the Optical Internetworking Forum (OIF) oversees the implementation efforts.

“The [GMPLS/ASON] control plane comprises a common part and technology-specific part,” says Hans-Martin Foisel, OIF president. The specific technologies include SONET/SDH, OTN, MPLS Transport Profile (MPLS-TP) and the all-optical layer.

"The more efficient, functional and powerful, the control plane, the better off operators will be"

"The more efficient, functional and powerful, the control plane, the better off operators will be"

Brandon Collings, JDS Uniphase.

“Using a control plane with all-optical is a challenge,” says Foisel. “The control plane has to have a very simplified knowledge of the optical parameters.” The photonic layer has numerous optical parameters that can be used. Any protocol needs to streamline the process such that simple rules are used by operators to decide whether a route can be completed or whether signal regeneration is needed.

The IETF is working on wavelength switched optical networks (WSON), the all-optical component of GMPLS, to enable such simplified rules within a single network domain. “GMPLS cannot control wavelengths today using ROADMs and that is what is being standardised in WSON,” says Persson.

What is beyond of scope of WSON is routing transparently between vendors, says Foisel. "It is almost impossible to indentify all the optical parameters in an inter-vendor way for operators to fully use,” says Fujitsu’s McDermott. "You end up with a huge parameter set."

So what will the photonic control plane look like?

“The whole architecture of control will be different that what is done in the electrical domain,” says Berthold. It will combine three main functions. One is embedded intelligence that will learn fibre-route characteristics and optical parameters from the network, data which will use be by each vendor in a proprietary way. Another is a propagation modelling planning tool that will process data offline to determine the viable network paths. These paths will then be preloaded into network elements as well as recommendations as to the preferred ones to use to avoid contention. Finally, use will be made of the signalling to turn these paths up as rapidly as possible. “This is certainly not the same model as electrical,” says Berthold.

By combining electrical and optical switching, operators will be able to continually optimise their networks. “They can devolve their networks to the lowest cost and most power-efficient solution,” says Berthold.

Ciena, for example, is adding colourless-directionless ROADMs to its 3.6 terabit-per-second 5430 electrical switch. “When you start growing traffic from a low level you need electrical switches in many places in order to efficiently fill wavelengths,” says Berthold. “But as traffic grows there is more opportunity to bypass intermediate nodes with an optical path.” By tying the ROADM with the electric switch, traffic can be regroomed and electrical paths set up on-demand to continually optimise the network.

Challenges

Despite progress in ROADM hardware and control plane management, challenges remain before a remotely controlled all-ROADM mesh network will be achieved.

One is handling customer application rates at 1, 10 and 40Gbps on 100 Gbps infrastructure. This will use the OTN protocol and will require electrical switch and control plane support.

Interoperability between vendors’ equipment must also be demonstrated. “Interlayer management – it is not enough just to do optical,” says Kline. “And it is not only between layers but interoperability between vendors’ equipment.” Thus, even if Verizon Business is correct that colourless, directionless ROADMs will become generally available in 2012; the vision of a dynamic optical network will take longer.

“Coherent technology for 40 Gig and 100 Gig is potentially a game changer in making ROADMs work”

“Coherent technology for 40 Gig and 100 Gig is potentially a game changer in making ROADMs work”

Joe Berthold, Ciena

“GMPLS/ASON are still years out and some operators may never deploy them,” says Schmitt at Infonetics. But Kline highlights the vendors Huawei and Alcatel-Lucent as keen promoters of control-plane-enabled dynamic optical networking.

“Huawei has 250 ASON applications with over 80 carriers, and 30-plus OTN WDM ASON applications,” says Kline. Here, an ASON application is described a ring or nodes that use a control plane for automated networking. “These are small and self-contained; not AT&T’s and Verizon’s [sized] meshed networks,” says Kline, who adds that Alcatel-Lucent also has such ASON deployments.

There are also business-case hurdles associated with photonic switching to be overcome.

Doing things on-demand may be compelling but need to be proven, says Jim King, executive director of new technology product development and engineering at AT&T Labs. This is easier to prove deeper in the network. “In the middle of the network it is easy because the law of large numbers means I know I need lots of capacity out of Chicago, say; I just don’t know whether it needs to go north, east or south,” says King. “But when a just-in-time delivery requirement extends to the end of the network, the financials are much more challenging based on how close you need to get to customer premises, cell towers or critical customer data centres.”

What next?

Oclaro too believes that it will be another two years before colourless, directionless and contentionless ROADMs start to be deployed in volume. The challenge thereafter is driving down their cost.

Another development that is likely to emerge after gridless is faster switching speeds to reduce network latency. Operators are using their mesh networks for restoration but there is a growing interest in protection and restoration at the optical layer, says Bala. “We were seeing RFPs (request-for-proposals) where a WSS of below 2s was ok,”’ he says. “Now it is: ‘How fast can you switch?’ and “Can you switch below 100ms’.”

This is driving interest in optical channel monitoring. “Ultimately it will require the ability to monitor the ROADM ports from signal power and to detect contention, and you’ll need to do this quickly,” says Wigley. “It is not very useful having a fast WSS unless you know quickly where the traffic is going.”

Technology will continue to provide incremental enhancements. The cost-per-bit-per-kilometer has come down six or seven orders of magnitude in the last two decade, says Finisar’s Poole. Apart from the erbium-doped fibre amplifier (EDFA), no single technology has made such a sizable contribution. Rather it has been a sequence of multiple incremental optimisations. “Coherent technology is one way of getting more data down a pipe; gridless is another to get a 2x improvement down a pipe,” says Poole. “Each of these is incremental, but you have to keep doing these steps to drive the cost-per-bit down.”

Meanwhile operators will look to further efficiencies to keep driving down transport costs. “Operators are looking at tradeoffs of router versus optical switching,” says McDermott. “They are going through various tradeoffs, the new services they might offer, and what is a flexible but cost effective solution.” As yet there is no universal agreement, he says.

“The balance between the two [the optical and electrical layer] is the key,” says Infinera’s Perkins. “There is a balance you have to reach to achieve the best economics: the lowest cost network supporting the highest capacity possible at a cost you can afford, and operate it with the fewest people.”

And ROADMs will be deployed more widely. “In 3-5 years’ time everything will have a ROADM in it – it better have a ROADM in it,” says Kline. At the electrical layer it will be Ethernet and at the optical it will be OTN and lightpaths. “It is all about simplification and saving costs.”

Other dynamic optical network briefing sections

Part 1: Still some way to go

Part 2: ROADMS: reconfigurable but still not agile

ROADMS: When "-less" is more

One only has to look at neighbouring IT and cloud computing in particular with its PaaS, IaaS and SaaS (Platform-, Infrastructure- and Software-as-a-Service).

But when it comes to agile optical networking and the reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexer (ROADM), what is notable is the smarts that are being added and yet all are described using the “-less” suffix: colourless, directionless, contentionless and gridless.

These are all logical names once the enhancements they add are explained. But as Infonetics Research analyst Andrew Schmitt has pointed out, the industry could do better with its naming schemes. Even the most gifted sales person may be challenged selling the merits of a colourless, directionless product.

Colourless is a term long in use for such optical devices as arrayed-waveguide gratings. So to expect the industry to change now is perhaps unrealistic. But could better names be chosen? And does it matter?

Well, yes, if it undersells the benefits new products deliver.

The four smarts

Colourless refers to the decoupling of the wavelength dependency, so is “wavelength independent” better? What about colourful? Sales people are on a better footing already.

Then there is directionless. The idea here is that the latest ROADMs have full flexibility in routing a lightpath to any of the network interface ports. So instead of directionless, what about ROADMs that are omnidirectional or all-directional?

"Even the most gifted sales person may be challenged selling the merits of a colourless, directionless product."

Contentionless means non-blocking, a well-known term widely used to describe switch and router designs.

And gridless comes from the concept of relaxing the rigid ITU grid for wavelengths. Again, a perfectly logical name. But it sells short the adaptive channel widths that new ROADMs will support for data rates above 100 Gigabit-per-second.

So third-generation ROADMs are colourless, directionless, contentionless and gridless products. But does colourful, all-directional, non-blocking and adaptive-channel ROADMs sound better?

Suggestions welcome.