100 Gigabit: An operator view

Gazettabyte spoke with BT, Level 3 Communications and Verizon about their 100 Gigabit optical transmission plans and the challenges they see regarding the technology.

Briefing: 100 Gigabit

Part 1: Operators

Operators will use 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) coherent technology for their next-generation core networks. For metro, operators favour coherent and have differing views regarding the alternative, 100Gbps direct-detection schemes. All the operators agree that the 100Gbps interfaces - line-side and client-side - must become cheaper before 100Gbps technology is more widely deployed.

"It is clear that you absolutely need 100 Gig in large parts of the network"

Steve Gringeri, Verizon

100 Gigabit status

Verizon is already deploying 100Gbps wavelengths in its European and US networks, and will complete its US nationwide 100Gbps backbone in the next two years.

"We are at the stage of building a new-generation network because our current network is quite full," says Steve Gringeri, a principal member of the technical staff at Verizon Business.

The operator first deployed 100Gbps coherent technology in late 2009, linking Paris and Frankfurt. Verizon's focus is on 100Gbps, having deployed a limited amount of 40Gbps technology. "We can also support 40 Gig coherent where it makes sense, based on traffic demands," says Gringeri.

Level 3 Communications and BT, meanwhile, have yet to deploy 100Gbps technology.

"We have not [made any public statements regarding 100 Gig]," says Monisha Merchant, Level 3’s senior director of product management. "We have had trials but nothing formal for our own development." Level 3 started deploying 40Gbps technology in March 2009.

BT expects to deploy new high-speed line rates before the year end. "The first place we are actively pursuing the deployment of initially 40G, but rapidly moving on to 100G, is in the core,” says Steve Hornung, director, transport, timing and synch at BT.

Operators are looking to deploy 100Gbps to meet growing traffic demands.

"If I look at cloud applications, video distribution applications and what we are doing for wireless (Long Term Evolution) - the sum of all the traffic - that is what is putting the strain on the network," says Gringeri.

Verizon is also transitioning its legacy networks onto its core IP-MPLS backbone, requiring the operator to grow its base infrastructure significantly. "When we look at demands there, it is clear that you absolutely need 100 Gig in large parts of the network," says Gringeri.

Level 3 points out its network between any two cities has been running at much greater capacity than 100 Gbps so that demand has been there for years, the issue is the economics of the technology. "Right now, going to 100Gbps is significantly a higher cost than just deploying 10x 10Gbps," says Level 3's Merchant.

BT's core network comprises 106 nodes: 20 in a fully-meshed inner core, surrounded by an outer 86-node core. The core carries the bulk of BT's IP, business and voice traffic.

"We are taking specific steps and have business cases developed to deploy 40G and 100G technology: alternative line cards into the same rack," says Hornung.

Coherent and direct detection

Coherent has become the default optical transmission technology for operators' next-generation core networks.

BT says it is a 'no-brainer' that 400Gbps and 1 Terabit-per-second light paths will eventually be deployed in the network to accommodate growing traffic. "Rather than keep all your options open, we need to make the assumption that technology will essentially be coherent going forward because it will be the bandwidth that drives it," says Hornung.

Beyond BT's 106-node core is a backhaul network that links 1,000 points-of-presence (PoPs). It is this part of the network that BT will consider 40Gbps and perhaps 100Gbps direct-detection technology. "If it [such technology] became commercially available, we would look at the price, the demand and use it, or not, as makes sense," says Hornung. "I would not exclude at this stage looking at any technology that becomes available." Such direct-detection 100Gbps solutions are already being promoted by ADVA Optical Networking and MultiPhy.

However, Verizon believes coherent will also be needed for the metro. "If I look at my metro systems, you have even lower quality amplifiers, and generally worse signal-to-noise," says Gringeri. “Based on the performance required, I have no idea how you are going to implement a solution that isn't coherent."

Even for shorter reach metro systems - 200 or 300km- Verizon believes coherent will be the implementation, including expanding existing deployments that carry 10Gbps light paths and that use dispersion-compensated fibre.

Level 3 says it is not wedded to a technology but rather a cost point. As a result it will assess a technology if it believes it will address the operator's needs and has a cost performance advantage.

100 Gig deployment stages

The cost of 100Gbps technology remains a key challenge impeding wider deployment. This is not surprising since 100Gbps technology is still immature and systems shipping are first-generation designs.

Operators are willing to pay a premium to deploy 100Gbps light paths at network pinch-points as it is cheaper that lighting a new fibre.

Metro deployments of new technology such as 100Gbps occur generally occur once the long-haul network has been upgraded. The technology is by then more mature and better suited to the cost-conscious metro.

Applications that will drive metro 100Gbps include linking data centre and enterprises. But Level 3 expects it will be another five years before enterprises move from requesting 10 Gigabit services to 100 Gigabit ones to meet their telecom needs.

Verizon highlights two 100Gbps priorities: the high-end performance dense WDM systems and client-side 'grey' (non-WDM) optics used to connect equipment across distances as short as 100m with ribbon cable to over 2km or 10km over single-mode fibre.

"I would not exclude at this stage looking at any technology that becomes available"

Steve Hornung, BT

"Grey optics are very costly, especially if I’m going to stitch the network and have routers and other client devices and potential long-haul and metro networks, all of these interconnect optics come into play," says Gringeri.

Verizon is a strong proponent of a new 100Gbps serial interface over 2km or 10km. At present there are the 100 Gigabit interface and the 10x10 MSA. However Gringeri says it will be 2-3 years before such a serial interface becomes available. "Getting the price-performance on the grey optics is my number one priority after the DWDM long haul optics," says Gringeri.

Once 100Gbps client-side interfaces do come down in price, operators' PoPs will be used to link other locations in the metro to carry the higher-capacity services, he says.

The final stage of the rollout of 100Gbps will be single point-to-point connections. This is where grey 100Gbps comes in, says Gringeri, based on 40 or 80km optical interfaces.

Source: Gazettabyte

Tackling costs

Operators are confident regarding the vendors’ cost-reduction roadmaps. "We are talking to our clients about second, third, even fourth generation of coherent," says Gringeri. "There are ways of making extremely significant price reductions."

Gringeri points to further photonic integration and reducing the sampling rate of the coherent receiver ASIC's analogue-to-digital converters. "With the DSP [ASIC], you can look to lower the sampling rate," says Gringeri. "A lot of the systems do 2x sampling and you don't need 2x sampling."

The filtering used for dispersion compensation can also be simpler for shorter-reach spans. "The filter can be shorter - you don't need as many [digital filter] taps," says Gringeri. "There are a lot of optimisations and no one has made them yet."

There are also the move to pluggable CFP modules for the line-side coherent optics and the CFP2 for client-side 100Gbps interfaces. At present the only line-side 100Gbps pluggable is based on direct detection.

"The CFP is a big package," says Gringeri. "That is not the grey optics package we want in the future, we need to go to a much smaller package long term."

For the line-side there is also the issue of the digital signal processor's (DSP) power consumption. "I think you can fit the optics in but I'm very concerned about the power consumption of the DSP - these DSPs are 50 to 80W in many current designs," says Gringeri.

One obvious solution is to move the DSP out of the module and onto the line card. "Even if they can extend the power number of the CFP, it needs to be 15 to 20W," says Gringeri. "There is an awful lot of work to get where you are today to 15 to 20W."

* Monisha Merchant left Level 3 before the article was published.

Further Reading:

100 Gigabit: The coming metro opportunity - a position paper, click here

Click here for Part 2: Next-gen 100 Gig Optics

MultiPhy boosts 100 Gig direct-detection using digital signal processing

The MP1100Q chip is being aimed at two cost-conscious metro networking requirements: 100 Gigabit point-to-point links and dense wavelength-division multiplexing (DWDM) metro networks.

The MP1100Q as part of a 100 Gig CFP module design. Source: MultiPhy

The MP1100Q as part of a 100 Gig CFP module design. Source: MultiPhy

The 100 Gigabit market is still in its infancy and the technology has so far been used to carry traffic across operators’ core networks. Now 100 Gigabit metro applications are emerging.

Data centre operators want short links that go beyond the IEEE-specified 10km (100GBASE-LR4) and 40km (100GBASE-ER4) reach interfaces, while enterprises are looking to 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) DWDM solutions to boost the capacity and reach of their rented fibre. Existing 100Gbps coherent technologies, designed for long-haul, are too expensive and bulky for the metro.

“There is long-haul and the [IEEE] client interfaces and a huge gap in between,” says Avishay Mor, vice president of product management at MultiPhy.

It is this metro 'gap' that MultiPhy is targeting with its MQ1100Q chip. And the fabless chip company's announcement is one of several that have been made in recent weeks.

ADVA Optical Networking has launched a 100Gbps metro line card that uses a direct-detection CFP, while Transmode has detailed a 100Gbps coherent design tailored for the metro. The 10x10 MSA announced in August a 10km interface as well as a 40km WDM design alongside its existing 10x10Gbps MSA that has a 2km reach.

MultiPhy's MP1100Q IC will enable two CFP module designs: a point-to-point module to connect data centres with a reach of up to 80km, and a DWDM design for metro core and regional networks with a reach up to 800km.

"MLSE is recognised as the best solution for mitigating inter-symbol interference."

Design details

The M1100Q uses a 4x28Gbps direct-detection design, the same approach announced by ADVA Optical Networking for its 100Gbps metro card. But MultiPhy claims that the 100Gbps DWDM CFP module will squeeze the four bands that make up the 100Gbps signal into a 100GHz-wide channel rather than 200GHz, while its IC implements the maximum likelihood sequence estimation (MLSE) algorithm to achieve the 800km reach.

The four optical channels received by a CFP are converted to electrical signals using four receiver optical subassemblies (ROSAs) and sampled using the MP1100Q’s four analogue-to-digital (a/d) converters operating at 28Gbps.

The CFP design using MultiPhy’s chip need only use 10Gbps opto-electronics for the transmit and receive paths. The result is a 100Gbps module with a cost structure based on 4x10Gbps optics.

The lower bill-of-materials impacts performance, however. “When you over-drive these 10Gbps opto-electronics - on the transmit and the receive side - you create what is called inter-symbol interference," says Neal Neslusan, vice president of sales and marketing at MultiPhy.

Inter-symbol interference is an unwanted effect where the energy of a transmitted bit leaks into neighboring signals. This increases the bit-error rate and makes the detector's task harder. "The way that we get around it is using MLSE, recognised as the best solution for mitigating inter-symbol interference," says Neslusan.

Unwanted channel effects introduced by the fibre, like chromatic dispersion, also induce inter-symbol interference and are also countered by the MLSE algorithm on the MP1100Q.

MultiPhy is proposing two CFP designs for its chip. One is based on on-off-keying modulation to achieve 80km point-to-point links and which will require a 200GHz channel to accommodate the 100Gbps signal. The second uses optical duo-binary modulation to achieve the longer reach and more spectrally efficient 100GHz spacings.

The company says the resulting direct-detection CFP using its IC will cost some US $10,000 compared to an estimated $50,000 for a coherent design. In turn the 100G metro CFP’s power consumption is estimated at 24W whereas a coherent design consumes 70W.

MP1100Q samples have been with the company since June, says Mor. First samples will be with customers in the fourth quarter of this year, with general availability starting in early 2012.

If all goes to plan, first CFP module designs using the chip will appear in the second half of 2012, claims MultiPhy.

Rafik Ward Q&A - final part

"Feedback we are getting from customers is that the current 100 Gig LR4 modules are too expensive"

Rafik Ward, Finisar

Q: Broadway Networks, why has Finisar acquired the company?

A: We spent quite some time talking to Broadway and understanding their business. We also talked to Broadway’s customers and the feedback we got on the technical team, the products and what this little start-up was able to accomplish was unanimously very positive.

We think what Broadway has done, for instance their EPON* stick product, is very interesting. With that product, an end user has the ability to make any SFP* port on a low-end Ethernet switch an EPON ONU* interface. This opens up a whole new set of potential customers and end users for EPON.

In reality, consumers will never have Ethernet switches with SFP ports in their house. Where we do see such Ethernet switches are in every major enterprise and many multi-dwelling units. It is an interesting technology that enables enterprises and multi-dwelling units to quickly tool-up for EPON.

* [EPON - Ethernet passive optical network, SFP - small form-factor pluggable optical transceiver, ONU - optical network unit]

Optical transceivers have been getting smaller and faster in the last decade yet laser and photo-detector manufacturing have hardly changed, except in terms of speed. Is this about to change?

Speed is one of the focus areas for the industry and will continue to be. Looking forward in a number of applications, though, we are going to hit the limit for these lasers and we are going to have to look more carefully outside of just raw laser speed to move up the data rate curve.

"We are going to hit the limit for these lasers"

A lot of this work has already started on the line side using different modulation formats and DSP* technology. Over time the question is: What happens on the client side? In future, do we look to other modulation formats on the client side? Eventually we will get there; it may take several years before we need to do things like that. But as an industry we would be foolish to think we won’t have to do this.

WDM* is going to be an increasingly important technology on the client side. We are already seeing this with the 40GBASE-LR4 and 100GBASE-LR4 standards.

* [DSP - digital signal processing, WDM - wavelength-division multiplexing]

Google gave a presentation at ECOC that argued for the need for another 100Gbps interface. What is Finisar’s view?

Feedback we are getting from customers is that the current 100 Gig LR4 modules are too expensive. We have spent a lot of time with customers helping them understand how the current LR4 standard, as is written, actually enables a very low cost optical interface, and the timeframes we believe are very quick in terms of how we can get cost down considerably on 100 Gig.  Rafik Ward (right) giving Glenn Wellbrock, director of backbone network design at Verizon Business, a tour of Finisar's labsThat was part of the details that [Finisar’s] Chris Cole also presented at ECOC.

Rafik Ward (right) giving Glenn Wellbrock, director of backbone network design at Verizon Business, a tour of Finisar's labsThat was part of the details that [Finisar’s] Chris Cole also presented at ECOC.

There has certainly been a lot of media attention on the two [ECOC] presentations between Finisar and Google. This really is not so much about the quote, ‘drama’, or two companies that have a disagreement which optical interface makes more sense. It is more fundamental than that.

What it comes down to is that, as an industry, we have pretty limited resources. The best thing all of us can do is try to direct these resources – this limited pool we have combined throughout the industry - on a path that makes the most sense to reduce bandwidth cost most significantly.

The best way to do that, and that is already established, is through standards. The [IEEE] standard got it right that the path the industry is on is going to enable the lowest cost 100 Gig [interface]. Like everything, there is some investment required to get us there. The 25 Gig technology now [used as 4x25 Gig] is becoming mainstream and will soon enable the lowest cost solution. My view is that within 18 months to two years this will be a moot point.

If the technology was available 18 months sooner, we wouldn’t even be having this discussion. But that is the position that we, as an industry, are in. With that, it creates some tensions, some turmoil, where customers don’t like to pay more than they perceive they have to.

There is the CFP form factor that is relatively large. Is the point that if current technology was available 18 months ago, 100Gbps could have come out in a QSFP?

The heart of the debate is cost.

There are other elements that always play into a debate like this. Beyond the cost argument, how quickly can two optical interfaces, like a 4x25 Gig versus a 10x10 Gig, each enable a smaller form factor solution.

But I think that is secondary. Had we not had the cost problem that we have now between 4x25 Gig versus 10x10 Gig, I don’t think we would be talking about it.

So it’s the current cost of the 4x25 Gig that is the issue?

Correct.

In September, the ECOC conference and exhibition was held. What were your impressions and did you detect any interesting changes?

There wasn’t so much an overwhelming theme this year at ECOC. In ECOC 2009, it was the year of coherent detection. This year there wasn’t a theme that resonated strongly throughout.

The mood was relatively upbeat. From our perspective, ECOC seemed a little bit smaller in terms of the size of the floor. But all the key people you would expect to be at the show were there.

Maybe the strongest theme – and I wrote about this in my blog – was colourless, directionless, contentionless (CDC) [ROADMs]. I think what I said is that they should have renamed it not ECOC but the ECDC show.

"A blog ... enables a much more informal mechanism to communicate to a broad audience."

Do you read business books and is there one that is useful for your job?

Probably the book I think about the most in my job is Clayton Christensen's The Innovator’s Dilemma.

He talks about how, when you look at very successful technology companies that have failed, what causes them to fail is often new solutions that come from the very low end of the market.

A lot of companies, and he cites examples from the disk drive industry, prided themselves on focussing on the high end of the market but ultimately ended up failing because there was a surprise upstart, someone who came in at the market's low end – in terms of performance, cost etc. – that continued to innovate using their low-end architecture, making it suitable for the core market.

For these large, well-established companies, once they realised they had this competitor, it was too late.

I think about that business book probably more than others. It’s a very interesting take on technology and the threat that can be posed to people in high-tech companies.

Your job sounds intensive and demanding. What do you do outside work to relax?

I’m a big [ice] hockey fan. I’ve been a hockey fan for many years; it’s a pretty intense sport. These days I tend to watch more hockey than I play but I very much enjoy the sport.

The other thing I started up this year that I had never done before – a little side project – was vegetable gardening. Surprisingly, it ended up taking a lot of my attention and I think it was a good distraction for me.

It can be quite remarkable, when you have your own little vegetable garden, how often you go and look at its progress. I’d find often coming home from work, first thing I’d want to do is go see how things were progressing in my vegetable garden.

You are the face of Finisar’s blog. What have you learnt from the experience?

A blog is an interesting tool to get information out to a broad audience. For companies like Finisar, it serves as a very important communication vehicle that didn’t exist previously.

In the old days, if you wanted to get information out to a broad group of customers, you either had to meet and communicate that information face-to-face, or via email; very targeted, one customer-at-a-time communication.

Another way was the press release. A press release was a very easy way to broadcast that information. But the challenge is that not all information that you want to broadcast is suitable for a press release.

The reason why I really like the blog is that it enables a much more informal mechanism to communicate to a broad audience.

Has it helped your job in any tangible way?

We found some interesting customer opportunities. These have come in through the blog when we’ve talked about specific products. That hasn’t happened extremely frequently but we have had a few instances. So it’s probably the most tangible thing: we can point to enhanced business because of it.

But the strength of something like a blog goes much deeper than that, in terms of the communication vehicle it enables.

You have about a year’s experience running a blog. If an optical component company is thinking about starting a blog, what is your advice?

The best advice I can give to anybody looking to do a blog is that it is something you have to commit to up-front.

A blog where you don’t continue to refresh the content regularly becomes a tired blog very quickly. We have made a conscious effort to have updated postings as best we can, on a weekly basis or even more frequently. There are certainly periods where we have gone longer than that but if you look back, in general, we have a wide variety of content that has been refreshed regularly.

I have to give credit to others - guest bloggers - within the organisation that help to maintain the content. This is critical. I would struggle to keep up with the pace if it was just myself every week.

Click here for the first part of Rafik Ward's Q&A.

Optical transceivers: Pouring a quart into a pint pot

Optical equipment and transceiver makers have much in common. Both must contend with the challenge of yearly network traffic growth and both are addressing the issue similarly: using faster interfaces, reducing power consumption and making designs more compact and flexible.

Yet if equipment makers and transceiver vendors share common technical goals, the market challenges they face differ. For optical transceiver vendors, the challenges are particularly complex.

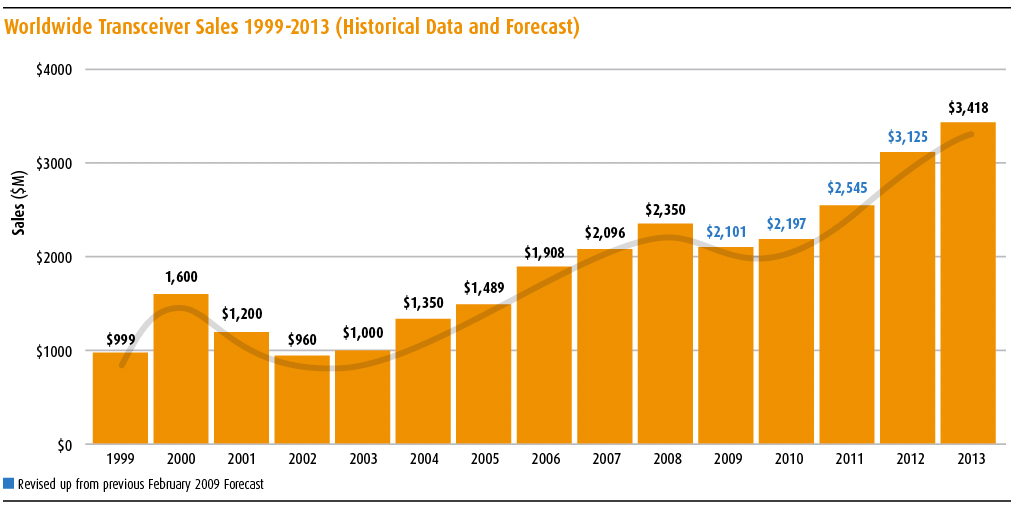

LightCounting's global optical transceiver sales forecast. In 2009 the market was $2.10bn and will rise to $3.42bn in 2013

LightCounting's global optical transceiver sales forecast. In 2009 the market was $2.10bn and will rise to $3.42bn in 2013

Transceiver vendors have little scope for product differentiation. That’s because the interfaces are based on standard form factors defined using multi-source agreements (MSAs).

System vendors may welcome MSAs since it increases their choice of suppliers but for transceiver vendors it means fierce competition, even for new opportunities such as 40 and 100 Gigabit Ethernet (GbE) and 40 and 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) long-haul transmission.

Transceiver vendors must also contend with 40Gbps overlapping with the emerging 100Gbps market. Vendors must choose which interface options to back with their hard-earned cash.

Some industry observers even question the 40 and 100Gbps market opportunities given the continual cost reduction and simplicity of 10Gbps transceivers. One is Vladimir Kozlov, CEO of optical transceiver market research firm, LightCounting.

“The argument heard is that 40Gbps will take over the world in two or three years’ time,” says Kozlov. Yet he has been hearing the same claim for over a decade: “Look at the relative prices of 40Gbps and 10Gbps a decade ago and look at it now – 10Gbps is miles ahead.”

In Kozlov’s view, while 40Gbps and 100Gbps are being adopted in the network, the vast majority of networks will not see such rates. Instead traffic growth will be met with additional 10Gbps wavelengths and where necessary more fibre.

“Look at the relative prices of 40Gbps and 10Gbps a decade ago and look at it now – 10Gbps is miles ahead.”

Vladimir Kozlov, LightCounting.

And despite the activity surrounding new pluggable transceivers such as the 40 and 100Gbps CFP MSA and long-haul modulation schemes, his view is that “99% of the market is about simplicity and low cost”.

Juniper Networks, in contrast, has no doubt 100Gbps interfaces will be needed.

First demand for 100Gbps will be to simplify data centre connections and link the network backbone. “Link aggregating 10Gbps channels involves multiple fibres and connections,” says Luc Ceuppens, senior director of marketing, high-end systems business unit at Juniper. “Having a single 100 Gigabit interface simplifies network topology and connections.”

Longer term, 100Gbps will be driven when the basic currency of streams exceeds 10Gbps. “You won’t have to parse a greater-than-10 Gig stream over two 10Gbps links,” says Ceuppens.

But faster line rates is only one way equipment vendors are tackling traffic growth and networking costs.

"Forty Gig and eventually 100 Gig are basic needs for data centre connections and backbone networks, but in the metro, higher line rate is not the only way to handle traffic growth cost effectively,” says Mohamad Ferej, vice president of R&D at Transmode. He points to lowering equipment’s cost, power consumption and size as well as enhancing its flexibility.

Compact designs equate to less floor space in the central office, while the energy consumption of platforms is a growing concern. Tackling both reduce operational expenses.

Greater platform flexibility using tunable components and pluggable transceivers also helps reduce costs. Tunable-laser-based transceivers slash the number of spare fixed-wavelength dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) transceivers operators and system vendors must store. Meanwhile, pluggables reduce costs by increasing competition and decoupling optics from the line card.

For higher speed interfaces, optical transmission cost – the cost-per-bit-per-kilometre - is reduced only if the new interface’s bandwidth grows faster than its cost relative to existing interfaces. The rule-of-thumb is that the transition to a new 4x line rate occurs once it matches 2.5x the existing interface’s cost. This is how 10Gbps superceded 2.5Gbps rates a decade ago.

The reason widespread adoption of 40Gbps has not happened is that 40Gbps has still to meet the crossover threshold. Indeed by 2012, 40Gbps will only be at 4x 10Gbps’ cost, according to market research firm, Ovum.

Thus it is the economics of 40 and 100Gbps as well as power and size that preoccupies module vendors.

Modulation war

“If the 40Gbps module market is at Step 1, 10Gbps is at Step 4,” says ECI Telecom’s Oren Marmur, vice president, optical networking line of business, network solutions division. Ten Gigabit has gone through several transitions; from 300-pin large form factor (LFF) to 300-pin small form factor (SFF) to the smaller fixed-wavelength pluggable XFP and now the tunable XFP. “Forty Gig is where 10 Gig modules were three years’ ago - each vendor has a different form factor and a different modulation scheme,” says Marmur.

DPSK dominates 40Gbps module shipments

DPSK dominates 40Gbps module shipments

Niall Robinson, Mintera

There are four modulation scheme choices for 40Gbps. First deployed has been optical duo-binary, followed by two phased-based modulation schemes: differential phase-shift keying (DPSK) and differential quadrature phase-shift keying (DQPSK). The phase modulation schemes offer superior reach and robustness to dispersion but are more complex and costly designs.

Added to the three is the emerging dual-polarisation, quadrature phase-shift keying (DP-QPSK), already deployed by operators using Nortel’s system and now being developed as a 300-pin LFF transponder by Mintera and JDS Uniphase. Indeed several such designs are expected in 2010.

Mintera has been shipping its 300-pin LFF adaptive DPSK transponder, and claims DPSK dominates 40Gbps module shipments. “DQPSK is being shipped in Japan and there is some interest in China but 90% is DPSK,” says Niall Robinson, vice president of product marketing at Mintera.

Opnext offers four 40Gbps transponder types: duo-binary, DPSK, a continuous mode DPSK variant that adapts to channel conditions based on the reconfigurable optical add/drop multiplexing (ROADM) stages a signal encounters, and a DQPSK design.

"40Gbps coherent channel position must be managed"

Daryl Inniss, Ovum

According to an Ovum study, duo-binary is cheapest followed by DPSK. The question facing transponder vendors is what next? Should they back DQPSK or a 40Gbps coherent DP-QPSK design?

“The problem with DQPSK is that it is more costly, though even coherent is somewhat expensive,” says Daryl Inniss, practice leader components at Ovum. The transponders’ bill of materials is only part of the story; optical performance being the other factor.

DQPSK has excellent performance when encountering dispersion while 40Gbps coherent channel position must be managed when used alongside 10Gbps wavelengths in the fibre. “It is not a big deal but it needs to be managed,” says Inniss. If price declines for the two remain equal, DQPSK will have the larger volumes, he says.

Another consideration is 100Gbps modules. DP-QPSK is the industry-backed modulation scheme for 100Gbps and given the commonality between 40 and 100Gbps coherent designs, the issue is their relative costs.

“The right question people are asking is what are the economics of 40 Gig versus 100 Gig coherent,” says Rafik Ward, Finisar's vice president of marketing. “If you buy 40 Gig and shortly after an economical 100 Gig coherent design appears, will 40 Gig coherent get the required market traction?”

Meanwhile, designers are shrinking existing 40Gbps modules, boosting significantly 40Gbps system capacity.

The 300-pin LFF transponder, at 7x5 inch, requires its own line card. As such, two system line cards are needed for a 40Gbps link: one for the short-reach, client-side interface and one for the line-side transponder.

A handful: a 300-pin large form factor transponder Source: Mintera

A handful: a 300-pin large form factor transponder Source: Mintera

Mintera is one vendor developing a smaller 300-pin MSA DPSK transponder that will enable the two 40Gbps interfaces on one card.

“At present there are 16 slots per shelf supporting eight 40Gbps links, and three shelves per bay,” says Robinson. Once vendors design a new line card, system capacity will double with 16, 40Gbps links (640Gbps) per shelf and 1,920Gbps capacity per system. Equipment vendors can also used the smaller pin-for-pin compatible 300-pin MSA on existing cards to reduce costs.

Matt Traverso, senior manager, technical marketing at Opnext also stresses the importance of more compact transponders: “Right now though it is a premature. The issue still is the modulation format war.”

Another factor driving transponder development is the electrical interface used. The 300-pin MSA uses the SFI 5.1 interface based on 16, 2.5Gbps channels. “Forty and 100GbE all use 10Gbps interfaces, as do a lot of framer and ASIC vendors,” says Traverso. Since the 300-pin MSA in not compatible, adopting 10Gbps-channel electrical interfaces will likely require a new pluggable MSA for long haul.

CFP MSA for 40 and 100 Gig

One significant MSA development in 2009 was the CFP pluggable transceiver MSA. At ECOC last September, several companies announced first CFP designs implementing 40 and 100GbE standards.

Opnext announced a 100GBASE-LR4 CFP, a 100GbE over 10 km interface made up of four wavelengths each at 25Gbps. Finisar and Sumitomo Electric each announced a 40GBASE-LR4 CFP, a 40GbE over 10km comprising four wavelengths at 10Gbps.

The CFP MSA is smaller than the 300-pin LFF, measuring some 3.4x4.8 inches (86x120mm). It has four power settings - up to 8W, up to 16W, below 24W and above 24W (to 32W). When a CFP is plugged in, it communicates to the host platform its power class.

The 100Gbps CFP is designed to link IP routers, or an IP router to a DWDM platform for longer distance transmission.

“There is customer-pull to get the 100 Gig [pluggable] out,” says Traverso, explaining why Opnext chose 100GbE for its first design.

Opnext’s 100GbE pluggable comprises four 25Gbps transmit optical sub-assemblies (TOSAs) and four receive optical sub-assemblies (ROSAs). Also included are an optical multiplexer and demultiplexer to transmit and recover the four narrowly (LAN-WDM) spaced wavelengths. Also included within the 100GbE CFP are two integrated circuits (ICs): a gearbox IC translating between the 10Gbps channels and the higher speed 25Gbps lanes, and the module’s electrical interface IC.

"The issue still is the modulation format war”

Matt Traverso, Opnext

The CFP transceiver, while relatively large, has space constraints that challenge the routeing of fibres linking the discrete optical components. “This is familiar territory,” says Traverso. “The 10GBASE-LX4 [a four-channel design] in an X2 [pluggable] was a much harder problem.”

“Right now our [100GbE] focus is the 10 km CFP,” says Juniper’s Ceuppens. “There is no interest in parallel multimode [100GBASE-SR10] - service providers will not deploy multi-mode fibre due to the bigger cable and greater weight.”

Finisar’s and Sumitomo Electric’s 40GBASE-LR4 CFP also uses four TOSAs and ROSAs, but since each is 10Gbps no gearbox IC is needed. Moreover, coarse WDM (CWDM)-based wavelength spacing is used avoidng the need for thermal cooling. The cooling is required for 100Gbps to restrict the lasers’ LAN-WDM wavelengths drifting. Finisar has since detailed a 100GBASE-LR4 CFP.

“For the 40GBASE-LR4 CFP, a discrete design is relatively straightforward,” says Feng Tian, senior manager marketing, device at Sumitomo Electric Device Innovations. Vendors favour discretes to accelerate time-to-market, he says. But with second generation designs, power and cost reduction will be achieved using photonic integration.

Reflex Photonics announced dual 40GBASE-SR4 transceivers within a CFP in October 2009. The SR4 specification uses a 4-channel multimode ribbon cable for short reach links up to 150 m. The short reach CFP designs will be used for connecting routers to DWDM platforms for telecom and to link core switch platforms within the largest data centres. “Where the number of [10Gbps] links becomes unwieldy,” says Robert Coenen, director of product management at Reflex Photonics.

Reflex’s 100GbE design uses a 12x photo-detector array and a 12x VCSEL array. For the 100GbE design, 10 of the 12 channels are used, while for the 2x40GbE, eight (2x4) channels of each array are used (see diagram). “We didn’t really have to redesign [the 100GbE]; just turn off two lanes and change the fibering,” says Coenen.

Meanwhile switch makers are already highlighting a need for more compact pluggables than the CFP.

“The CFP standard is OK for first generation 100Gbps line cards but denser line cards are going to require a smaller form factor,” says Pravin Mahajan, technology marketer at Cisco Systems.

This is what Cube Optics is addressing by integrating four photo-detectors and a demultiplexer in a sub-assembly using its injection molding technology. Its 4x25Gbps ROSA for 100GbE complements its existing 4x10 CWDM ROSA for 40GbE applications.

“The CFP is a nice starting point but there must be something smaller, such as a QSFP or SFP+,” says Sven Krüger, vice president product management at Cube Optics.

The company has also received funding for the development of complementary 4x25Gbps and 4x10Gbps TOSA functions. “The TOSA is more challenging from an optical alignment point of view; the lasers have a smaller coupling area,” says Francis Nedvidek, Cube Optic’s CEO.

Cube Optics forecasts second generation 40GbE and 100GbE transceiver designs using its integrated optics to ship in volume in 2011.

Could the CFP be used beyond 100GbE for 100Gbps line side and the most challenging coherent design?

“The CFP with its smaller size is a good candidate,” says Sumitomo’s Tian. “But power consumption will be a challenge.” It may require one and maybe two more CMOS process generations to be used beyond the current 65nm to reduce the power consumption sufficiently for the design to meet the CFP’s 32W power limit, he says.

XFP put to new uses

Established pluggables such as the 10Gbps XFP transceiver also continue to evolve.

Transmode is shipping XFP-based tunable lasers with its systems, claiming the tunable XFP brings significant advantages.

In turn, Menara Networks is incorporating system functionality within the XFP normally found only on the line card.

Until now deploying fixed-wavelength DWDM XFPs meant a system vendor had to keep a sizable inventory for when an operator needed to light new DWDM wavelengths. “With no inventory you have to wait for a firm purchase order from your customer before you know which wavelengths to order from your transceiver vendor, and that means a 12-18 weeks delivery time,” says Ferej. Now with a tunable XFP, one transceiver meets all the operator’s wavelength planning requirements.

Moreover, the optical performance of the XFP is only marginally less than a tunable 10Gbps 300-pin SFF MSA. “The only advantage of a 300-pin is a 2-3dB better optical signal-to-noise ratio, meaning the signal can pass more optical amplifiers, required for longer reach” says Ferej.

Using a 300-pin extends the overall reach without a repeater beyond 1,000 km. “But the majority of the metro network business is below 1000 km,” says Ferej.

Does the power and space specifications of an MSA such as the XFP matter for component vendors or do they just accept it?

“It doesn’t matter till it matters,” says Padraig OMathuna, product marketing director at optical device maker, GigOptix. The maximum power rating for an XFP is 3.5W. “If you look inside a tunable XFP, the thermo-electric cooler takes 1.5 to 2W, the laser 0.5W and then there is the TIA,” says OMathuna. “That doesn’t leave a lot of room for our modulator driver.”

Inside JDS Uniphase's tunable XFP

Inside JDS Uniphase's tunable XFP

Meanwhile, Menara Networks has implemented the ITU-T’s Optical Transport Network (OTN) in the form of an application specific IC (ASIC) within an XFP.

OTN is used to encapsulate signals for transport while adding optical performance monitoring functions and forward error correction. By including OTN within a pluggable, signal encapsulation, reach and optical signal management can be added to IP routers and carrier Ethernet switch routers.

The approach delivers several advantages, says Siraj ElAhmadi, CEO of Menara Networks.

First, it removes the need for additional 10Gbps transponders to ready the signals from the switch or router for DWDM transport. Second, system vendors can develop a universal linecard without supporting OTN functionality.

The biggest technical challenge for Menara was not developing the OTN ASIC but the accompanying software. “We had the chip one and a half years before we shipped the product because of the software,” says ElAhmadi. “There is no room [within the XFP] for extra memory.”

Menara is supplying its OTN pluggables to a North American cable operator.

ECI Telecom is one vendor using Menara’s pluggable for its carrier Ethernet switch router (CESR) platforms. “For certain applications it saves you having to develop OTN,” says Jimmy Mizrahi, next-generation networking product line manager, network solutions division at ECI Telecom.

Pluggables and optical engines

The CFP is one module that will be used in the data center but for high density applications - linking switches and high-performance computing - more compact designs are needed. These include the QSFP, the CXP and what are being called optical engines.

The CFP form factor for 40 and 100Gbps

The CFP form factor for 40 and 100Gbps

The QSFP is already the favoured interface for active optical cables that encapsulate the optics within the cable and which provide an attractive alternative to copper interconnect. QSFP transceivers support quad data rate (QDR) 4xInfiniband as well as extending the reach of 4x10Gbps Ethernet beyond copper’s 7m.

The QSFP is also an option for more compact 40GbE short-reach interfaces. “The [40GBASE-]SR4 is doable today as a QSFP,” says Christian Urricarriet, 40, 100GbE, and parallel product line manager at Finisar. The 40-GBASE-LR4 in a QSFP is also possible, as targeted by Cube Optics among others.

Achieving 100GbE within a QSFP is another matter. Adding a 25Gbps-per-channel electrical interface and higher-speed lasers while meeting the QSFP’s power constraints is a considerable challenge. “There may need to be an intermediate form factor that is better defined [for the task],” says Urricarriet.

Meanwhile, the CXP is a front panel interface that promises denser interfaces within the data centre. “CXP is useful for inter-chassis links as it stands today,” says Cisco’s Mahajan.

According to Avago Technologies, Infiniband is the CXP’s first target market while 100GbE using 10 of the 12 channels is clearly an option. But there are technical challenges to be overcome before the CXP connector can be used for 100GbE Ethernet. “You need to be much more stringent to meet the IEEE optical specification,” says Sami Nassar, director of marketing, fiber optic products division at Avago Technologies.

The CXP is also entering territory until recently the preserve of the SNAP12 parallel optics module. SNAP12 connects the platforms within large IP router configurations, and is used for high-end computing. However, it is not a pluggable and comprises separate 12-channel transmitter and receiver modules. SNAP12 has a 6.25Gbps per channel data rate although a 10Gbps per channel has been announced.

“Both [the CXP and SNAP12] have a role,” says Reflex’s Coenen. SNAP12 is on the mother board and because it has a small form factor it can sit close to the ASIC, he says.

Such an approach is now being targeted by firms using optical engines to reduce the cost of parallel interfaces and address emerging high-speed interface requirements on the mother-board, between racks and between systems.

Luxtera’s OptoPHY is one such optical engine. There are two versions: a single channel 10Gbps and a 4x10Gbps product, while a 12-channel version will sample later this year.

The OptoPHY uses the same optical technology as Luxtera’s AOC: a 1490nm distributed feedback (DFB) laser is used for both one and four-channel products, modulated using the company’s silicon photonics technology. The single channel consumes 450mW while the four-channel consumes 800mW, says Marek Tlalka, vice president of marketing at Luxtera, while reach is up to 4km.

Luxtera says the 12-channel version which will cost around $120, equating to $1 per 1Gbps. This, it claims, is several times cheaper than SNAP12.

“The next-generation product will achieve 25Gbps per channel, using the same form factor and the same chip,” says Tlalka. This will allow the optical engine to handle channel speeds used for 100GbE as well as the next Infiniband speed-hike known as Eight Data Rate (EDR).

Avago, a leading supplier of SNAP12, says that the robust interface with its integrated heat sink is still a preferred option for vendors. “For others, with even higher-density concentrations, a next generation packaging type is being used, which we’ve not announced yet,” says Dan Rausch, Avago’s senior technical marketing manager, fiber optic products division.

The advent of 100GbE and even higher rates, and 25Gbps electrical interfaces, will further promote optical engines. “It is hard enough to route 10Gbps around an FR4 printed circuit board,” says Coenen. Four inches are typically the limit, while longer links up to 10 inches requiring such techniques as pre-emphasis, electronic dispersion compensation and retiming.

At 25Gbps distances will become even shorter. “This makes the argument for optical engines even stronger, you will need them near the ASICs to feed data to the front panel,” says Coenen.

Optical transceivers may rightly be in the limelight handling network traffic growth but it is the activities linking platforms, boards and soon on-board devices where optical transceiver vendors, unencumbered by MSAs, have scope for product differentiation.

Do multi-source agreements benefit the optical industry?

System vendors may adore optical transceivers but there is a concern about how multi-source agreements originate.

Optical transceiver form factors, defined through multi-source agreements (MSAs), benefit equipment vendors by ensuring there are several suppliers to choose from. No longer must a system vendor develop its own or be locked in with a supplier.

“Personally, the MSA is the worst thing that has happened to the optical industry”

“Personally, the MSA is the worst thing that has happened to the optical industry”

Marek Tlaka, Luxtera

Pluggables also decouple optics from the line card. A line card can address several applications simply by replacing the module. In contrast, with fixed optics the investment is tied to the line card. A system can also be upgraded by swapping the module with an enhanced specification version once it is available.

But given the variety of modules that datacom and telecom system vendors must support, there are those that argue the MSA process should be streamlined to benefit the industry.

Traditionally, several transceiver vendors collaborate before announcing an MSA. The CFP MSA announced in March 2009, for example, was defined by Finisar, Opnext and Sumitomo Electric Device Innovations. Since then Avago Technologies has become a member.

“The industry has an interesting model,” says Niall Robinson, vice president of product marketing at Mintera. “A couple of companies can get together, work behind closed doors and announce suddenly an MSA and try to make it defacto in the market.”

Robinson contrasts the MSA process with the Optical Interconnecting Forum’s (OIF) 100Gbps line side work that defined guidelines for integrated transmitter and receiver modules. Here service providers and system vendors also contributed. “It was a much more effective and fair process, allowing for industry collaboration,” says Robinson

Matt Traverso, senior manager, technical marketing at Opnext, and involved in the CFP MSA, also favours an open process. “But the view that the way MSAs are run is not open is a bit of a fallacy,” he says.

“Any MSA that is well run requires iteration with suppliers,” says Traverso. The opposite is also true: poorly run MSAs have short lives, he says. Having too open a forum also runs the risk of creating a one-size-fits-all: “One vendor may want to use the MSA as a copper interface while a carrier will want it for long-haul dense WDM.”

Optical transceiver vendors benefit in another way if they are the ones developing MSAs. “Transceiver vendors will not make life tough for themselves,” says Padraig OMathuna, product marketing director at optical device maker, GigOptix. “If MSAs are defined by system vendors, [transceiver] designs would be a lot more challenging.”

Avago Technologies argues for standards bodies to play a role especially as industry resources become more thinly spread.

“MSAs are not standards; there are items left unwritten and not enough double checking is done,” says Sami Nassar, director of marketing, fiber optic products division at Avago Technologies. There are always holes in the specifications, requiring patches and fixes. “If they [transceivers] were driven by standards bodies that would be better,” says Nassar.

Organisations such as the IEEE don’t address packaging and connectors as part of their standards work. But this may have to change. “The real challenge, as the industry thins out, is ensuring the [MSA] work is thorough,” says Dan Rausch, Avago’s senior technical marketing manager, fiber optic products division. “The challenge for the industry going forward is ensuring good engineering and more robust solutions.”

Marek Tlalka, vice president of marketing at Luxtera, goes further, questioning the very merits of the MSA: “Personally, the MSA is the worst thing that has happened to the optical industry.”

Unlike the semiconductor industry where a framer chip once on a line card delivers revenue for years, a transceiver company may design the best product yet six months later be replaced by a cheaper competitor. “The return on investment is lost; all that work for nothing,” says Tlalka.

“Is it a good development or not? MSAs are out there,” says Vladimir Kozlov, CEO of optical transceiver market research firm, LightCounting. “It helps system vendors, giving them a freedom to buy.”

But MSAs have squeezed transceiver makers, says Kozlov, and he worries that it is hindering innovation as companies cut costs to maximize their return on investment.

“There is continual pressure to reduce the price of optics,” adds Daryl Inniss, Ovum’s practice leader components. If operators are to provide video and high definition TV services and grow revenues then bandwidth needs to become dirt cheap. “Even today optics is not cheap,” says Inniss. Certainly MSAs play an important role in reducing costs.

“The transceiver vendors’ challenge is our benefit,” admits Oren Marmur, vice president, optical networking line of business, network solutions division at system vendor, ECI Telecom. “But we have our own challenges at the system level.”

Optical transceivers: Useful references

Industry bodies

The CFP Multi-Source Agreement (MSA): The hot-pluggable optical transceiver form factor for 40Gbps and 100Gbps applications

Useful articles on optical transceivers

- CFP, CXP form factors complementary, not competitive, Lightwave magazine

- The difference between CFP and CXP, Lightspeed blog

|

Company |

Comment |

|

System vendors |

|

|

ZTE |

ZXR10 T8000 core router with up to 2,048 40Gbps or 1,024 100Gbps interfaces |

|

|

|

|

Optical transceivers |

|

|

Finisar |

40GBASE-LR4 CFP: A 40 Gigabit Ethernet (GbE) LR4 CFP transceiver |

|

Opnext |

100GBASE-LR4 CFP: The 100GbE optical transceiver standard for 10km. Sept 2009. |

|

Reflex Photonics |

Dual 40Gbps CFP: Two 40GBASE-SR4 specification for 40G Ethernet links up to 150m. Oct 2009 |

|

Sumitomo Electric |

40GBASE-LR4: The 40GbE CFP module for 10km transmission. Sept 2009 |

|

Menara Networks |

XFP OTN |

Table 1: Company announcements