NeoPhotonics' PIC transceiver tackles PON business case

Gazettabyte completes its summary of optical announcements at ECOC, held in Amsterdam. In the third and final part, NeoPhotonics’ GPON multiport transceiver is detailed.

Part 3: NeoPhotonics

“Anything that can be done to get high utilisation of your equipment, which represents your up-front investment, helps the business case"

“Anything that can be done to get high utilisation of your equipment, which represents your up-front investment, helps the business case"

Chris Pfistner, NeoPhotonics

NeoPhotonics has announced a Gigabit passive optical network (GPON) transceiver designed to tackle the high up-front costs operators face when deploying optical access.

The GPON optical line terminal (OLT) transceiver has a split ratio of 1:128 - a passive optical network (PON) supporting 128 end points - yet matches the optical link budget associated with smaller split ratios. The transceiver, housed in an extended SFP module, has four fibre outputs, each supporting a conventional GPON OLT. The transceiver also uses a mode-coupling receiver implemented using optical integration.

According to NeoPhotonics, carriers struggle with the business case for PON given the relatively low take-up rates by subscribers, at least initially. “Anything that can be done to get high utilisation of your equipment, which represents your up-front investment, helps the business case,” says Chris Pfistner, vice president of product marketing at NeoPhotonics. “With a device like this, you can now cover four times the area you would normally cover.”

The GPON OLT transceiver, the first of a family, has been tested by operator BT that has described the technology as promising.

Reach and split ratio

The GPON transceiver supports up to 128 end points yet meets the GPON Class B+ 28dB link budget optical transceiver specification.

The optical link budget can be traded to either maximise the PON’s distance, limited due to the loss per fibre-km, or to support higher split ratios. However, a larger split ratio increases the insertion loss due to the extra optical splitter stages the signal passes through. Each 1:2 splitter introduces a 3.5dB loss, eroding the overall optical link budget and hence the PON’s reach.

GPON was specified with a Class B 20dB and Class C 30dB link budget. However once PON deployments started a 28dB Class B+ was created to match the practical requirements of operators. For Verizon, for example, a reach of 10-11km covers 95% of its single family units, says NeoPhotonics.

Operators wanting to increase the split ratio to 1:64 need an extra 4dB. This has led to the 32dB link budget Class C+. For shorter runs, in such cases as China, the Class C+ is used for a 1:128 split ratio. “They [operators] are willing to give up distance to cover an extra 1-by-2 split,” says Pfistner.

NeoPhotonics supports the 1:128 split ratio without suffering such loss by introducing two techniques: the mode-coupling receiver (MCR) and boosting the OLT transceiver's transmitter power.

A key issue dictating a PON performance is the sensitivity of the OLT's burst mode receiver. The upstream fibres are fed straight onto the NeoPhotonics’ MCR, eliminating the need for a 4x1 combiner (inverse splitter) and a resulting 6dB signal loss.

The GPON OLT transceiver showing the transmit and the mode-coupling receiver. Source: NeoPhotonics

The MCR is not a new concept, says Pfistner, and can be implemented straightforwardly using bulk optics. But such an implementation is relatively large. Instead, NeoPhotonics has implemented the MCR as a photonic integrated circuit (PIC) fitting the design within an extended SFP form factor.

“The PIC draws on our long experience of planar lightwave circuit technology, and [Santur’s] indium phosphide array technology, to do fairly sophisticated devices,” says Pfistner. NeoPhotonics acquired Santur in 2011.

The resulting GPON transceiver module fits within an SFP slot but it is some 1.5-2cm longer than a standard OLT SFP. Most PON line cards support four or eight OLT ports. Pfistner says a 1:4 ratio is the sweet spot for initial rollouts but higher ratios are possible.

On the transmit side, the distributed feedback (DFB) laser also goes through a 1:4 stage which introduces a 6dB loss. The laser transmit power is suitably boosted to counter the 6dB loss.

Operators

BT has trialled the optical performance of a transceiver prototype. “BT confirmed that the four outputs each represents a Class B+ GPON OLT output,” says Pfistner. Some half a dozen operators have expressed an interest in the transceiver, ranging from making a request to working with samples.

China is one market where such a design is less relevant at present. That is because China is encouraging through subsidies the rollout of PON OLTs even if the take-up rate is low. Pfistner, quoting an FTTH Council finding, says that there is a 5% penetration typically per year: “Verizon has been deploying PON for six years and has about a 30% penetration.”

Meanwhile, an operator only beginning PON deployments will first typically go after the neighbourhoods where a high take-up rate is likely and only then will it roll out PON in the remaining areas.

After five years, a 25% uptake is achieved, assuming this 5% uptake a year. At a 4x higher split ratio, that is the same bandwidth per user as a standard OLT in a quarter of the area, says NeoPhotonics.

“One big concern that we hear from operators is: Now I'm sharing the [PON OLT] bandwidth with 4x more users,” says Pfistner. “That is true if you believe you will get to the maximum number of users in a short period, but that is hardly ever the case.”

And although the 1:128 split ratio optical transceiver accounts for a small part of the carrier’s PON costs, the saving the MCR transceiver introduces is at the line card level. "That means at some point you are going to save shelves and racks [of equipment],” says Pfistner.

Roadmap

The next development is to introduce an MCR transceiver that meets the 32dB Class C+ specification. “A lot of carriers are about to make the switch from B+ to C+ in the GPON world,” says Pfistner. There will also be more work to reduce the size of the MCR PIC and hence the size of the overall pluggable form factor.

Beyond that, NeoPhotonics says a greater than 4-port split is possible to change the economics of 10 Gigabit PON, for GPON and Ethernet PON. “There are no deployments right now because the economics are not there,” he adds.

“The standards effort is focussed on the 'Olympic thought': higher bandwidth, faster, further reach, mode-coupling receiver (MCR) whereas the carriers focus is: How do I lower the up-front investment to enter the FTTH market?” says Pfistner.

Further reading:

GPON SFP Transceiver with PIC based Mode-Coupled Receiver, Derek Nesset, David Piehler, Kristan Farrow, Neil Parkin, ECOC Technical Digest 2012 paper.

Lightwave: Mode coupling receiver increases PON split ratios, click here

Ovum: Lowering optical transmission cost at ECOC 2012, click here

Summary Gazettabyte stories from ECOC 2012, click here

Huawei boosts its optical roadmap with CIP acquisition

Huawei has acquired UK photonic integration specialist, CIP Technologies, from the East of England Development Agency (EEDA) for an undisclosed fee. The acquisition gives the Chinese system vendor a wealth of optical component expertise and access to advanced European Union R&D projects.

"By acquiring CIP and integrating the company’s R&D team into Huawei’s own research team, Huawei’s optic R&D capabilities can be significantly enhanced," says Peter Wharton, CEO at the Centre for Integrated Photonics (CIP). CIP Technologies is the trading name of the Centre for Integrated Photonics.

Huawei now has six European R&D centres with the acquisition of CIP.

Huawei now has six European R&D centres with the acquisition of CIP.

CIP Technologies has indium phosphide as well as planar lightwave circuit (PLC) technology which it uses as the basis for its HyBoard hybrid integration technology. HyBoard allows actives to be added to a silica-on-silicon motherboard to create complex integrated optical systems.

CIP has been using its photonic integration expertise to develop compact, more cost-competitive WDM-PON optical line terminal (OLT) and optical network unit (ONU) designs, including the development of an integrated transmitter array.

The company employs 50 staff, with 70% of its work coming from the telecom and datacom sectors. About a third of its revenues are from advanced products and two thirds from technical services.

The CEO of CIP says all current projects for its customers will be carried out as planned but CIP’s main research and development service will be focused on Huawei’s business priorities. “We expect all contracted projects to be completed and current customers are being assisted to find alternate sources of supply," says Wharton.

CIP is also part of several EU Seventh Framework programme R&D projects. These include BIANCHO, a project to reduce significantly the power consumption of optical components and systems, and 3CPO, which is developing colourless and coolerless optical components for low-power optical networks.

Huawei's acquisition will not affect CIP's continuing participation in such projects. "For EU framework and other collaborative R&D projects, the ultimate share ownership does not matter so long as it is a research organisation based in Europe, which CIP will continue to be," says Wharton.

CIP said it had interest from several potential acquirers but that the company favoured Huawei.

What this means

CIP has a rich heritage. It started as BT's fibre optics group. But during the optical boom of 1999-2000, BT shed its unit, a move also adopted by such system vendors as Nortel and Lucent.

The unit was acquired by Corning in 2000 but the acquisition did not prove a success and in 2002 the group faced closure before being rescued by the East of England Development Agency (EEDA).

CIP has always been an R&D organisation in character rather than a start-up. Now with Huawei's ambition, focus and deep pockets coupled with CIP's R&D prowess, the combination could prove highly successful if the acquisition is managed well.

Huawei's acquisition looks shrewd. Optical integration has been discussed for years but its time is finally arriving. The technologies of 40 Gigabit and 100 Gigabit is based on designs with optical functions in parallel; at 400 Gigabit the number of channels only increases.

Optical access will also benefit from photonic integration - from board optical sub-assemblies for GPON and EPON to WDM-PON to ultra dense WDM-PON. China is also the biggest fibre-to-the-x (FTTx) market by far.

A BT executive talking about the operator's 21CN mentioned how system vendors used to ask him repeatedly about Huawei. Huawei, in contrast, used to ask him about Infinera.

Huawei, like all the other systems vendors, has much to do to match Infinera's photonic integrated circuit expertise and experience. But the Chinese vendor's optical roadmap just got a whole lot stronger with the acquisition of CIP.

Further reading:

Reflecting light to save power, click here

100 Gigabit: An operator view

Gazettabyte spoke with BT, Level 3 Communications and Verizon about their 100 Gigabit optical transmission plans and the challenges they see regarding the technology.

Briefing: 100 Gigabit

Part 1: Operators

Operators will use 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) coherent technology for their next-generation core networks. For metro, operators favour coherent and have differing views regarding the alternative, 100Gbps direct-detection schemes. All the operators agree that the 100Gbps interfaces - line-side and client-side - must become cheaper before 100Gbps technology is more widely deployed.

"It is clear that you absolutely need 100 Gig in large parts of the network"

Steve Gringeri, Verizon

100 Gigabit status

Verizon is already deploying 100Gbps wavelengths in its European and US networks, and will complete its US nationwide 100Gbps backbone in the next two years.

"We are at the stage of building a new-generation network because our current network is quite full," says Steve Gringeri, a principal member of the technical staff at Verizon Business.

The operator first deployed 100Gbps coherent technology in late 2009, linking Paris and Frankfurt. Verizon's focus is on 100Gbps, having deployed a limited amount of 40Gbps technology. "We can also support 40 Gig coherent where it makes sense, based on traffic demands," says Gringeri.

Level 3 Communications and BT, meanwhile, have yet to deploy 100Gbps technology.

"We have not [made any public statements regarding 100 Gig]," says Monisha Merchant, Level 3’s senior director of product management. "We have had trials but nothing formal for our own development." Level 3 started deploying 40Gbps technology in March 2009.

BT expects to deploy new high-speed line rates before the year end. "The first place we are actively pursuing the deployment of initially 40G, but rapidly moving on to 100G, is in the core,” says Steve Hornung, director, transport, timing and synch at BT.

Operators are looking to deploy 100Gbps to meet growing traffic demands.

"If I look at cloud applications, video distribution applications and what we are doing for wireless (Long Term Evolution) - the sum of all the traffic - that is what is putting the strain on the network," says Gringeri.

Verizon is also transitioning its legacy networks onto its core IP-MPLS backbone, requiring the operator to grow its base infrastructure significantly. "When we look at demands there, it is clear that you absolutely need 100 Gig in large parts of the network," says Gringeri.

Level 3 points out its network between any two cities has been running at much greater capacity than 100 Gbps so that demand has been there for years, the issue is the economics of the technology. "Right now, going to 100Gbps is significantly a higher cost than just deploying 10x 10Gbps," says Level 3's Merchant.

BT's core network comprises 106 nodes: 20 in a fully-meshed inner core, surrounded by an outer 86-node core. The core carries the bulk of BT's IP, business and voice traffic.

"We are taking specific steps and have business cases developed to deploy 40G and 100G technology: alternative line cards into the same rack," says Hornung.

Coherent and direct detection

Coherent has become the default optical transmission technology for operators' next-generation core networks.

BT says it is a 'no-brainer' that 400Gbps and 1 Terabit-per-second light paths will eventually be deployed in the network to accommodate growing traffic. "Rather than keep all your options open, we need to make the assumption that technology will essentially be coherent going forward because it will be the bandwidth that drives it," says Hornung.

Beyond BT's 106-node core is a backhaul network that links 1,000 points-of-presence (PoPs). It is this part of the network that BT will consider 40Gbps and perhaps 100Gbps direct-detection technology. "If it [such technology] became commercially available, we would look at the price, the demand and use it, or not, as makes sense," says Hornung. "I would not exclude at this stage looking at any technology that becomes available." Such direct-detection 100Gbps solutions are already being promoted by ADVA Optical Networking and MultiPhy.

However, Verizon believes coherent will also be needed for the metro. "If I look at my metro systems, you have even lower quality amplifiers, and generally worse signal-to-noise," says Gringeri. “Based on the performance required, I have no idea how you are going to implement a solution that isn't coherent."

Even for shorter reach metro systems - 200 or 300km- Verizon believes coherent will be the implementation, including expanding existing deployments that carry 10Gbps light paths and that use dispersion-compensated fibre.

Level 3 says it is not wedded to a technology but rather a cost point. As a result it will assess a technology if it believes it will address the operator's needs and has a cost performance advantage.

100 Gig deployment stages

The cost of 100Gbps technology remains a key challenge impeding wider deployment. This is not surprising since 100Gbps technology is still immature and systems shipping are first-generation designs.

Operators are willing to pay a premium to deploy 100Gbps light paths at network pinch-points as it is cheaper that lighting a new fibre.

Metro deployments of new technology such as 100Gbps occur generally occur once the long-haul network has been upgraded. The technology is by then more mature and better suited to the cost-conscious metro.

Applications that will drive metro 100Gbps include linking data centre and enterprises. But Level 3 expects it will be another five years before enterprises move from requesting 10 Gigabit services to 100 Gigabit ones to meet their telecom needs.

Verizon highlights two 100Gbps priorities: the high-end performance dense WDM systems and client-side 'grey' (non-WDM) optics used to connect equipment across distances as short as 100m with ribbon cable to over 2km or 10km over single-mode fibre.

"I would not exclude at this stage looking at any technology that becomes available"

Steve Hornung, BT

"Grey optics are very costly, especially if I’m going to stitch the network and have routers and other client devices and potential long-haul and metro networks, all of these interconnect optics come into play," says Gringeri.

Verizon is a strong proponent of a new 100Gbps serial interface over 2km or 10km. At present there are the 100 Gigabit interface and the 10x10 MSA. However Gringeri says it will be 2-3 years before such a serial interface becomes available. "Getting the price-performance on the grey optics is my number one priority after the DWDM long haul optics," says Gringeri.

Once 100Gbps client-side interfaces do come down in price, operators' PoPs will be used to link other locations in the metro to carry the higher-capacity services, he says.

The final stage of the rollout of 100Gbps will be single point-to-point connections. This is where grey 100Gbps comes in, says Gringeri, based on 40 or 80km optical interfaces.

Source: Gazettabyte

Tackling costs

Operators are confident regarding the vendors’ cost-reduction roadmaps. "We are talking to our clients about second, third, even fourth generation of coherent," says Gringeri. "There are ways of making extremely significant price reductions."

Gringeri points to further photonic integration and reducing the sampling rate of the coherent receiver ASIC's analogue-to-digital converters. "With the DSP [ASIC], you can look to lower the sampling rate," says Gringeri. "A lot of the systems do 2x sampling and you don't need 2x sampling."

The filtering used for dispersion compensation can also be simpler for shorter-reach spans. "The filter can be shorter - you don't need as many [digital filter] taps," says Gringeri. "There are a lot of optimisations and no one has made them yet."

There are also the move to pluggable CFP modules for the line-side coherent optics and the CFP2 for client-side 100Gbps interfaces. At present the only line-side 100Gbps pluggable is based on direct detection.

"The CFP is a big package," says Gringeri. "That is not the grey optics package we want in the future, we need to go to a much smaller package long term."

For the line-side there is also the issue of the digital signal processor's (DSP) power consumption. "I think you can fit the optics in but I'm very concerned about the power consumption of the DSP - these DSPs are 50 to 80W in many current designs," says Gringeri.

One obvious solution is to move the DSP out of the module and onto the line card. "Even if they can extend the power number of the CFP, it needs to be 15 to 20W," says Gringeri. "There is an awful lot of work to get where you are today to 15 to 20W."

* Monisha Merchant left Level 3 before the article was published.

Further Reading:

100 Gigabit: The coming metro opportunity - a position paper, click here

Click here for Part 2: Next-gen 100 Gig Optics

R&D: At home or abroad?

Omer Industrial Park in the Negev, Israel - the location of ECI Telecom's latest R&D centre.

Omer Industrial Park in the Negev, Israel - the location of ECI Telecom's latest R&D centre.

Chaim Urbach likes working at the Omer Industrial Park site. Normally located at ECI’s headquarters in Petah Tikva, he visits the Omer site - some 100km away - once or twice a week and finds he is more productive there. Urbach employs an open door policy and has fewer interruptions at the Omer site since engineers are focussed solely on R&D work.

ECI set up its latest R&D centre in May 2010 with a staff of ten. “In 2009 we realised we needed more engineers,” says Urbach. One year on the site employs 150, by the end of the year it will be 200, and by year-end 2012 the company expects to employ 300. ECI has already taken one unit at the Industrial Park and its operations have already spilt over into a second building.

Urbach says that the decision to locate the new site in the south of Israel was not straightforward.

The company has 1,300 R&D staff, with research centres in the US, India and China. Having a second site in Israel helps in terms of issues of language and time zones but employing an R&D engineer in Israel is several times more costly than an engineer in India or China.

The photos on the wall are part of the winning entries in an ECI company-wide photo competition.

The photos on the wall are part of the winning entries in an ECI company-wide photo competition.

But the Israeli Government’s Office of the Chief Scientist (OCS) is keen to encourage local high-tech ventures and has helped with the funding of the site. In return the backed-venture must undertake what is deemed innovative research with the OCS guaranteed royalties from sales of future telecom systems developed at the site.

One difficulty Urbach highlights is recruiting experienced hardware and software engineers given that there are few local high-tech companies in the south of the country. Instead ECI has relocated experienced engineering managers from Petah Tikva, tasked with building core knowledge by training graduates from nearby Ben-Gurion University and from local colleges.

Work on the majority of ECI’s new projects in being done at the Omer site, says Urbach. Projects include developing GPON access technology for a BT tender as well as extending its successful XDM hybrid+ SDH to all-IP transport platform, which has over 30% market share in India. ECI is undertaking the research on one terabit transmission using OFDM technology, part of the Tera Santa Consortium, at its HQ.

“We realised we needed more engineers”

“We realised we needed more engineers”

Chaim Urbach, ECI Telecom

Urbach admits it is a challenge to compete with leading Far Eastern system vendors on cost and given their R&D budgets. But he says the company is focussed on building innovative platforms delivered as part of a complete solution. “We do not just provide a box,” says Urbach. “And customers know if they have a problem, we go the extra mile to solve it.”

Omer Industrial Park

The company is highly business oriented, he says, delivering solutions that fit customers’ needs. “Over 95% of all systems ECI has developed have been sold,” he says.

Urbach also argues that Israeli engineers are suited to R&D. “Engineers don’t do everything by the book,” he says. “And they are dedicated and motivated to succeed.”

For more photos of the Omer Industrial Park, click here

Operators want to cut power by a fifth by 2020

Part 2: Operators’ power efficiency strategies

Service providers have set themselves ambitious targets to reduce their energy consumption by a fifth by 2020. The power reduction will coincide with an expected thirty-fold increase in traffic in that period. Given the cost of electricity and operators’ requirements, such targets are not surprising: KPN, with its 12,000 sites in The Netherlands, consumes 1% of the country’s electricity.

“We also have to invest in capital expenditure for a big swap of equipment – in mobile and DSLAMs"

Philippe Tuzzolino, France Telecom-Orange

Operators stress that power consumption concerns are not new but Marga Blom, manager, energy management group at KPN, highlights that the issue had become pressing due to steep rises in electricity prices. “It is becoming a significant part of our operational expense,” she says.

"We are getting dedicated and allocated funds specifically for energy efficiency,” adds John Schinter, AT&T’s director of energy. “In the past, energy didn’t play anywhere near the role it does today.”

Power reduction strategies

Service providers are adopted several approaches to reduce their power requirements.

Upgrading their equipment is one. Newer platforms are denser with higher-speed interfaces while also supporting existing technologies more efficiently. Verizon, for example, has deployed 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) interfaces for optical transport and for its IT systems in Europe. The 100Gbps systems are no larger than existing 10Gbps and 40Gbps platforms and while the higher-speed interfaces consume more power, overall power-per-bit is reduced.

“There is a business case based on total cost of ownership for migrating to newer platforms.”

“There is a business case based on total cost of ownership for migrating to newer platforms.”

Marga Blom, KPN

Reducing the number of facilities is another approach. BT and Deutsche Telekom are reducing significantly the number of local exchanges they operate. France Telecom is consolidating a dozen data centres in France and Poland to two, filling both with new, more energy-efficient equipment. Such an initiative improves the power usage effectiveness (PUE), an important data centre efficiency measure, halving the energy consumption associated with France Telecom’s data centres’ cooling systems.

“PUE started with data centres but it is relevant in the future central office world,” says Brian Trosper, vice president of global network facilities/ data centers at Verizon. “As you look at the evolution of cloud-based services and virtualisation of applications, you are going to see a blurring of data centres and central offices as they interoperate to provide the service.”

Belgacom plans to upgrade its mobile infrastructure with 20% more energy-efficient equipment over the next two years as it seeks a 25% network energy efficiency improvement by 2020. France Telecom is committed to a 15% reduction in its global energy consumption by 2020 compared to the level in 2006. Meanwhile KPN has almost halted growth in its energy demands with network upgrades despite strong growth in traffic, and by 2012 it expects to start reducing demand. KPN’s target by 2020 is to reduce energy consumption by 20 percent compared to its network demands of 2005.

Fewer buildings, better cooling

Philippe Tuzzolino, environment director for France Telecom-Orange, says energy consumption is rising in its core network and data centres due to the ever increasing traffic and data usage but that power is being reduced at sites using such techniques as virtualisation of servers, free-air cooling, and increasing the operating temperature of equipment. “We employ natural ventilation to reduce the energy costs of cooling,” says Tuzzolino.

“Everything we do is going to be energy efficient.”

“Everything we do is going to be energy efficient.”

Brian Trosper, Verizon

Verizon uses techniques such as alternating ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ aisles of equipment and real-time smart-building sensing to tackle cooling. “The building senses the environment, where cooling is needed and where it is not, ensuring that the cooling systems are running as efficiently as possible,” says Trosper.

Verizon also points to vendor improvements in back-up power supply equipment such as DC power rectifiers and uninterruptable power supplies. Such equipment which is always on has traditionally been 50% efficient. “If they are losing 50% power before they feed an IP router that is clearly very inefficient,” says Chris Kimm, Verizon's vice president, network field operations, EMEA and Asia-Pacific. Now manufacturers have raised efficiencies of such power equipment to 90-95%.

France Telecom forecasts that its data centre and site energy saving measures will only work till 2013 with power consumption then rising again. “We also have to invest in capital expenditure for a big swap of equipment – in mobile and DSLAMs [access equipment],” says Tuzzolino.

Newer platforms support advanced networking technologies and more traffic while supporting existing technologies more efficiently. This allows operators to move their customers onto the newer platforms and decommission the older power-hungry kit.

“Technology is changing so rapidly that there is always a balance between installing new, more energy efficient equipment and the effort to reduce the huge energy footprint of existing operations”

John Schinter, AT&T

Operators also use networking strategies to achieve efficiencies. Verizon is deploying a mix of equipment in its global private IP network used by enterprise customers. It is deploying optical platforms in new markets to connect to local Ethernet service providers. “We ride their Ethernet clouds to our customers in one market, whereas layer 3 IP routing may be used in an adjacent, next most-upstream major market,” says Kimm. The benefit of the mixed approach is greater efficiencies, he says: “Fewer devices to deploy, less complicated deployments, less capital and ultimately less power to run them.”

Verizon is also reducing the real-estate it uses as it retires older equipment. “One trend we are seeing is more, relatively empty-looking facilities,” says Kimm. It is no longer facilities crammed with equipment that is the problem, he says, rather what bound sites are their power and cooling capacity requirements.

“You have to look at the full picture end-to-end,” says Trosper. “Everything we do is going to be energy efficient.” That includes the system vendors and the energy-saving targets Verizon demands of them, how it designs its network, the facilities where the equipment resides and how they are operated and maintained, he says.

Meanwhile, France Telecom says it is working with 19 operators such as Vodafone and Telefonica, BT, DT, China Telecom, and Verizon as well as the organisations such as the ITU and ETSI to define standards for DSLAMs and base stations to aid the operators in meeting their energy targets.

Tuzzolino stresses that France Telecom’s capital expenditure will depend on how energy costs evolve. Energy prices will dictate when France Telecom will need to invest in equipment, and the degree, to deliver the required return on investment.

The operator has defined capital expenditure spending scenarios - from a partial to a complete equipment swap from 2015 - depending on future energy costs. New services will clearly dictate operators’ equipment deployment plans but energy costs will influence the pace.

““If they [DC power rectifiers and UPSs] are losing 50% power before they feed an IP router that is clearly very inefficient”

““If they [DC power rectifiers and UPSs] are losing 50% power before they feed an IP router that is clearly very inefficient”

Chris Kimm, Verizon.

Justifying capital expenditure spending based on energy and hence operational expense savings in now ‘part of the discussion’, says KPN’s Blom: “There is a business case based on total cost of ownership for migrating to newer platforms.”

Challenges

But if operators are generally pleased with the progress they are making, challenges remain.

“Technology is changing so rapidly that there is always a balance between installing new, more energy efficient equipment and the effort to reduce the huge energy footprint of existing operations,” says AT&T’s Schinter.

“The big challenge for us is to plan the capital expenditure effort such that we achieve the return-on-investment based on anticipated energy costs,” says Tuzzolino.

Another aspect is regulation, says Tuzzolino. The EC is considering how ICT can contribute to reducing the energy demands of other industries, he says. “We have to plan to reduce energy consumption because ICT will increasingly be used in [other sectors like] transport and smart grids.”

Verizon highlights the challenge of successfully managing large-scale equipment substitution and other changes that bring benefits while serving existing customers. “You have to keep your focus in the right place,” says Kimm.

Part 1: Standards and best practices

Optical transmission beyond 100Gbps

Part 3: What's next?

Given the 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) optical transmission market is only expected to take off from 2013, addressing what comes next seems premature. Yet operators and system vendors have been discussing just this issue for at least six months.

And while it is far too early to talk of industry consensus, all agree that optical transmission is becoming increasingly complex. As Karen Liu, vice president, components and video technologies at market research firm Ovum, observed at OFC 2010, bandwidth on the fibre is no longer plentiful.

“We need to keep a very close eye that we are not creating more problems than we are solving.”

“We need to keep a very close eye that we are not creating more problems than we are solving.”

Brandon Collings, JDS Uniphase.

As to how best to extend a fibre’s capacity beyond 80, 100Gbps dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) channels spaced 50GHz apart, all options are open.

“What comes after 100Gbps is an extremely complicated question,” says Brandon Collings, CTO of JDS Uniphase’s consumer and commercial optical products division. “It smells like it will entail every aspect of network engineering.”

Ciena believes that if operators are to exploit future high-speed transmission schemes, new architected links will be needed. The rigid networking constraints imposed on 40 and 100Gbps to operate over existing 10Gbps networks will need to be scrapped.

“It will involve a much broader consideration in the way you build optical systems,” says Joe Berthold, Ciena’s vice president of network architecture. “For the next step it is not possible [to use existing 10Gbps links]; no-one can magically make it happen.”

Lightpaths faster than 100Gbps simply cannot match the performance of current optical systems when passing through multiple reconfigurable optical add/drop multiplexer (ROADM) stages using existing amplifier chains and 50GHz channels.

Increasing traffic capacity thus implies re-architecting DWDM links. “Whatever the solution is it will have to be cheap,” says Berthold. This explains why the Optical Internetworking Forum (OIF) has already started a work group comprising operators and vendors to align objectives for line rates above 100Gbps.

If new links are put in then changing the amplifier types and even their spacing becomes possible, as is the use of newer fibre. “If you stay with conventional EDFAs and dispersion managed links, you will not reach ultimate performance,” says Jörg-Peter Elbers, vice president, advanced technology at ADVA Optical Networking,

Capacity-boosting techniques

Achieve higher speeds while matching the reach of current links will require a mixture of techniques. Besides redesigning the links, modulation schemes can be extended and new approaches used such as going ‘gridless” and exploiting sophisticated forward error-correction (FEC) schemes.

For 100Gbps, polarisation and phase modulation in the form of dual polarization, quadrature phase-shift keying (DP-QPSK) is used. By adding amplitude modulation, quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM) schemes can be extended to include 16-QAM, 64-QAM and even 256 QAM.

Alcatel-Lucent is one firm already exploring QAM schemes but describes improving spectral efficiency using such schemes as a law of diminishing returns. For example, 448Gbps based on 64-QAM achieves a bandwidth of 37GHz and a sampling rate of 74 Gsamples/s but requires use of high-resolution A/D converters. “This is very, very challenging,” says Sam Bucci, vice president, optical portfolio management at Alcatel-Lucent.

Infinera is also eyeing QAM to extend the data performance of its 10-channel photonic integrated circuits (PICs). Its roadmap goes from today’s 100Gbps to 4Tbps per PIC.

Infinera has already announced a 10x40Gbps PIC and says it can squeeze 160 such channels in the C-band using 25GHz channel spacing. To achieve 1 Terabit would require a 10x100Gbps PIC.

How would it get to 2Tbps and 4Tbps? “Using advanced modulation technology; climbing up the QAM ladder,” says Drew Perkins, Infinera’s CTO.

Glenn Wellbrock, director of backbone network design at Verizon Business, says it is already very active in exploring rates beyond 100Gbps as any future rate will have a huge impact on the infrastructure. “No one expects ultra-long-haul at greater than 100Gbps using 16-QAM,” says Wellbrock.

Another modulation approach being considered is orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (OFDM). “At 100Gbps, OFDM and the single-carrier approach [DP-QPSK] have the same spectral efficiency,” says Jonathan Lacey, CEO of Ofidium. “But with OFDM, it’s easy to take the next step in spectral efficiency – required for higher data rates - and it has higher tolerance to filtering and polarisation-dependent loss.”

One idea under consideration is going “gridless”, eliminating the standard ITU wavelength grid altogether or using different sized bands, each made up of increments of narrow 25GHz ones. “This is just in the discussion phase so both options are possible,” says Berthold, who estimates that a gridless approach promises up to 30 percent extra bandwidth.

Berthold favours using channel ‘quanta’ rather than adopting a fully flexibility band scheme - using a 37GHz window followed by a 17GHz window, for example - as the latter approach will likely reduce technology choice and lead to higher costs.

Wellbrock says coarse filtering would be needed using a gridless approach as capturing the complete C-Band would be too noisy. A band 5 or 6 channels wide would be grabbed and the signal of interest recovered by tuning to the desired spectrum using a coherent receiver’s tunable laser, similar to how a radio receiver works.

Wellbrock says considerable technical progress is needed for the scheme to achieve a reach of 1500km or greater.

“Whatever the solution is it will have to be cheap”

“Whatever the solution is it will have to be cheap”

Joe Berthold, Ciena.

JDS Uniphase’s Collings sounds a cautionary note about going gridless. “50GHz is nailed down – the number of questions asked that need to be addressed once you go gridless balloons,” he says. “This is very complex; we need to keep a very close eye that we are not creating more problems than we are solving.”

“Operators such as AT&T and Verizon have invested heavily in 50GHz ROADMs, they are not just going to ditch them,” adds Chris Clarke, vice president strategy and chief engineer at Oclaro.

More powerful FEC schemes and in particular soft-decision FEC (SD-FEC) will also benefit optical performance for data rates above 100Gbps. SD-FEC delivers up to a 1.3dB coding gain improvement compared to traditional FEC schemes at 100Gbps.

SD-FEC also paves the way for performing joint iterative FEC decoding and signal equalisation at the coherent receiver, promising further performance improvements, albeit at the expense of a more complex digital signal processor design.

400Gbps or 1 Tbps?

Even the question of what the next data rate after 100Gbps will be –200Gbps, 400Gbps or even 1 Terabit-per -second – remains unresolved.

Verizon Business will deploy new 100Gbps coherent-optimised routes from 2011 and would like as much clarity as possible so that such routes are future-proofed. But Collings points out that this is not something that will stop a carrier addressing immediate requirements. “Do they make hard choices that will give something up today?” he says.

At the OFC Executive Forum, Verizon Business expressed a preference for 1Tbps lightpaths. While 400Gbps was a safe bet, going to 1Tbps would enable skipping one additional stage i.e. 400Gbps. But Verizon recognises that backing 1Tbps depends on when such technology would be available and at what cost.

According to BT, speeds such as 200, 400Gbps and even 1 Tbps are all being considered. “The 200/ 400Gbps systems may happen using multiple QAM modulation,” says Russell Davey, core transport Layer 1 design manager at BT. “Some work is already being done at 1Tbps per wavelength although an alternative might be groups or bands of wavelengths carrying a continuous 1Tbps channel, such as ten 100Gbps wavelengths or five 200Gbps wavelengths.”

Davey stresses that the industry shouldn’t assume that bit rates will continue to climb. Multiple wavelengths at lower bitrates or even multiple fibres for short distances will continue to have a role. “We see it as a mixed economy – the different technologies likely to have a role in different parts of network,” says Davey.

Niall Robinson, vice president of product marketing at Mintera, is confident that 400Gbps will be the chosen rate.

Traditionally Ethernet has grown at 10x rates while SONET/SDH has grown in four-fold increments. However now that Ethernet is a line side technology there is no reason to expect the continued faster growth rate, he says. “Every five years the line rate has increased four-fold; it has been that way for a long time,” says Robinson. “100Gbps will start in 2012/ 2013 and 400Gbps in 2017.”

“There is a lot of momentum for 400Gbps but we’ll have a better idea in a six months’ time,” says Matt Traverso, senior manager, technical marketing at Opnext. “The IEEE [and its choice for the next Gigabit Ethernet speed after 100GbE] will be the final arbiter.”

Software defined optics and cognitive optics

Optical transmission could ultimately borrow two concepts already being embraced by the wireless world: software defined radio (SDR) and cognitive radio.

SDR refers to how a system can be reconfigured in software to implement the most suitable radio protocol. In optical it would mean making the transmitter and receiver software-programmable so that various transmission schemes, data rates and wavelength ranges could be used. “You would set up the optical transmitter and receiver to make best use of the available bandwidth,” says ADVA Optical Networking’s Elbers.

This is an idea also highlighted by Nokia Siemens Networks, trading capacity with reach based on modifying the amount of information placed on a carrier.

“For a certain frequency you can put either one bit [of information] or several,” says Oliver Jahreis, head of product line management, DWDM at Nokia Siemens Networks. “If you want more capacity you put more information on a frequency but at a lower signal-to-noise ratio and you can’t go as far.”

Using ‘cognitive optics’, the approach would be chosen by the optical system itself using the best transmission scheme dependent capacity, distance and performance constraints as well as the other lightpaths on the fibre. “You would get rid of fixed wavelengths and bit rates altogether,” says Elbers.

Market realities

Ovum’s view is it remains too early to call the next rate following 100Gbps.

Other analysts agree. “Gridless is interesting stuff but from a commercial standpoint it is not relevant at this time,” says Andrew Schmitt, directing analyst, optical at Infonetics Research.

Given that market research firms look five years ahead and the next speed hike is only expected from 2017, such a stance is understandable.

Optical module makers highlight the huge amount of work still to be done. There is also a concern that the benefits of corralling the industry around coherent DP-QPSK at 100Gbps to avoid the mistakes made at 40Gbps will be undone with any future data rate due to the choice of options available.

Even if the industry were to align on a common option, developing the technology at the right price point will be highly challenging.

“Many people in the early days of 100Gbps – in 2007 – said: ‘We need 100Gbps now – if I had it I’d buy it’,” says Rafik Ward, vice president of marketing at Finisar. “There should be a lot of pent up demand [now].” The reason why there isn’t is that such end users always miss out key wording at the end, says Ward: “If I had it I’d buy it - at the right price.”

For Part 1, click here

For Part 2, click here

40 and 100Gbps: Growth assured yet uncertainty remains

Part 2: 40 and 100Gbps optical transmission

The market for 40 and 100 Gigabit-per-second optical transmission is set to grow over the next five years at a rate unmatched by any other optical networking segment. Such growth may excite the industry but vendors have tough decisions to make as to how best to pursue the opportunity.

Market research firm Ovum forecasts that the wide area network (WAN) dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) market for 40 and 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) linecards will have a 79% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) till 2014.

In turn, 40 and 100Gbps transponder volumes will grow even faster, at 100% CAGR till 2015, while revenues from 40 and 100Gbps transponder sale will have a 65% CAGR during the same period.

Yet with such rude growth comes uncertainty.

“We upgraded to 40Gbps because we believe – we are certain, in fact – that across the router and backbone it [40Gbps technology] is cheaper.”

Jim King, AT&T Labs

Systems, transponder and component vendors all have to decide what next-generation modulation schemes to pursue for 40Gbps to complement the now established differential phase-shift keying (DPSK). There are also questions regarding the cost of the different modulation options, while vendors must assess what impact 100Gbps will have on the 40Gbps market and when the 100Gbps market will take off.

“What is clear to us is how muddled the picture is,” says Matt Traverso, senior manager, technical marketing at Opnext.

Economics

Despite two weak quarters in the second half of 2009, the 40Gbps market continues to grow.

One explanation for the slowdown was that AT&T, a dominant deployer of 40Gbps, had completed the upgrade of its IP backbone network.

Andreas Umbach, CEO of u2t Photonics, argues that the slowdown is part of an annual cycle that the company also experienced in 2008: strong 40Gbps sales in the first half followed by a weaker second half. “In the first quarter of 2010 it seems to be repeating with the market heating up,” says Umbach.

This is also the view of Simon Warren, Oclaro’s director product line managenent, transmission product line. “We are seeing US metro demand coming,” he says. “And it is very similar with European long-haul.”

BT, still to deploy 40Gbps, sees the economics of higher-speed transmission shifting in the operator’s favour. “The 40Gbps wavelengths on WDM transmission systems have just started to cost in for us and we are likely to start using it in the near future,” says Russell Davey, core transport Layer 1 design manager at BT.

What dictates an operator upgrade from 10Gbps to 40Gbps, and now also to 100Gbps, is economics.

The transition from 2.5Gbps to 10Gbps lightpaths that began in 1999 occurred when 10Gbps approached 2.5x the cost of 2.5Gbps. This rule-of-thumb has always been assumed to apply to 40Gbps yet thousands of wavelengths have been deployed while 40Gbps remains more than 4x the cost of 10Gbps. Now the latest rule-of-thumb for 100Gbps is that operators will make the transition once 100Gbps reaches 2x 40Gbps i.e. gaining 25% extra bandwidth for free.

The economics is further complicated by the continuing price decline of 10Gbps. “Our biggest competitor is 10Gbps,” says Niall Robinson, vice president of product marketing at 40Gbps module maker Mintera.

“The traditional multiplier of 2.5x for the transition to 10Gbps is completely irrelevant for the 10 to 40 Gigabit and 10 to 100 Gigabit transitions,” says Andrew Schmitt, directing analyst of optical at Infonetics Research. “The transition point is at a higher level; even higher than cost-per-bit parity.”

So far two classes of operators adopting 40Gbps have emerged: AT&T, China Telecom and cable operator Comcast which have made, or plan, significant network upgrades to 40Gbps, and those such as Verizon Business and Qwest that have used 40Gbps more strategically for selective routes. For Schmitt there is no difference between the two: “These are economic decisions.”

AT&T is in no doubt about the cost benefits of moving to higher speed transmission. “We upgraded to 40Gbps because we believe – we are certain, in fact – that across the router and backbone it [40Gbps technology] is cheaper,” says Jim King, executive director of new technology product development and engineering, AT&T Labs.

King stresses that 40Gbps is cheaper than 10Gbps in terms of capital expenditure and operational expense. IP efficiencies result and there are fewer larger pipes to manage whereas at lower rates “multiple WDM in parallel” are required, he says.

“We see 100Gbps wavelengths on transmission systems available within a year or so, but we think the cost may be prohibitive for a while yet, especially given we are seeing large reductions in 10Gbps,” says Davey. BT is designing the line-side of new WDM systems to be compatible with 40Gbps – and later 100Gbps - even though it will not always use the faster line-cards immediately.

Even when an operator has ample fibre, the case for adopting 40Gbps on existing routes is compelling. That’s because lighting up new fibre is “enormous costly”, says Joe Berthold, Ciena’s vice president of network architecture. By adding 40Gbps to existing 10Gbps lightpaths at 50GHz channel spacing, capacity on an existing link is boosted and the cost of lighting up a separate fibre is forestalled.

According to Berthold, lighting a new fibre costs about the same as 80 dense DWDM channels at 10Gbps. “The fibre may be free but there is the cost of the amplifiers and all the WDM terminals,” he says. “If you have filled up a line and have plenty of fibre, the 81st channel costs you as much as 80 channels.”

The same consideration applies to metropolitan (metro) networks when a fibre with 40, 10Gbps channels is close to being filled. “The 41st channel also means six ROADMs (reconfigurable optical add/drop multiplexers) and amps which are not cheap compared to [40Gbps] transceivers,” says Berthold.

Alcatel-Lucent segments 40Gbps transmission into two categories: multiplexing of lower speed signals into a higher speed 40Gbps line-side trunk link - ‘muxing to trunk’ - and native 40Gbps transmission where the client-side, signal is at 40Gbps.

“The economics of the two are somewhat different,” says Sam Bucci, vice president, optical portfolio management at Alcatel-Lucent. The economics favour moving to higher capacity trunks. That said, Alcatel-Lucent is seeing native 40Gbps interfaces coming down in price and believes 100GbE interfaces will be ‘quite economical’ compared to 10x10Gbps in the next two years.

Further evidence regarding the relative expense of router interfaces is given by Jörg-Peter Elbers, vice president, advanced technology at ADVA Optical Networking, who cites that in overall numbers currently only 20% go into 40Gbps router interfaces while the remaining 80% go into muxponders.

Modulation Technologies

While economics dictate when the transition to the next-generation transmission speed occurs, what is complicating matters is the wide choice of modulation schemes. Four modulation technologies are now being used at 40Gbps with operators having the additional option of going to 100Gbps.

The 40Gbps market has already experienced one false start back in 2002/03. The market kicked off in 2005, at least that is when the first 40Gbps core router interfaces from Cisco Systems and Juniper Networks were launched.

"There is an inability for guys like us to do what we do best: take an existing interface and shedding cost by driving volumes and driving the economics.”

"There is an inability for guys like us to do what we do best: take an existing interface and shedding cost by driving volumes and driving the economics.”

Rafik Ward, Finisar

Since then four 40Gbps modulation schemes are now shipping: optical duobinary, DPSK, differential quadrature phase-shift keying (DQPSK) and polarisation multiplexing quadrature phase-shift keying (PM-QPSK). PM-QPSK is also referred to as dual-polarisation QPSK or DP-QPSK.

“40Gbps is actually a real mess,” says Rafik Ward, vice president of marketing at Finisar.

The lack of standardisation can be viewed as a positive in that it promotes system vendor differentiation but with so many modulation formats available the lack of consensus has resulted in market confusion, says Ward: “There is an inability for guys like us to do what we do best: take an existing interface and shedding cost by driving volumes and driving the economics.”

DPSK is the dominant modulation scheme deployed on line cards and as transponders. DPSK uses relatively simple transmitter and receiver circuitry although the electronics must operate at 40Gbps. DPSK also has to be modified to cope with tighter 50GHz channel spacing.

“DPSK’s advantage is relatively simple,” says Loi Nguyen, founder, vice president of networking, communications, and multi-markets at Inphi. “For 1200km it works fine, the drawback is it requires good fibre.”

The DQPSK and DP-QPSK modulation formats being pursued at 40Gbps offer greater transmission performance but are less mature.

DQPSK has a greater tolerance to polarisation mode dispersion (PMD) and is more resilient when passing through cascaded 50GHz channels compared to DPSK. However DQPSK uses more complex transmitter and receiver circuitry though it operates at half the symbol rate – at 20Gbaud/s - simplifying the electronics.

DP-QPSK is even more complex than DQPSK requiring twice as much optical circuitry due to the use of polarisation multiplexing. But this halves again the symbol rate to 10Gbaud/s, simplifying the design constraints of the optics. However DP-QPSK also requires a complex application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) to recover signals in the presence of such fibre-induced signal impairments as chromatic dispersion and PMD.

The ASIC comprises high-speed analogue-to-digital converters (ADCs) that sample the real and imaginary components that are the output of the DP-QPSK optical receiver circuitry, and a digital signal processor (DSP) which performs the algorithms to recovery the original transmitted bit stream in the presence of dispersion.

The chip is costly to develop – up to US $20 million – but its use reduces line costs by allowing fewer optical amplifiers numbers and removing PMD and chromatic dispersion in-line compensators.

“You can build more modular amplifiers and really optimise performance/ cost,” says Bucci. Such benefits only apply when a new optimised route is deployed, not when 40Gbps lightpaths are added to existing fibre carrying 10Gbps lightpaths.

Eliminating dispersion compensation fibre in the network using coherent detection brings another important advantage, says Oliver Jahreis, head of product line management, DWDM at Nokia Siemens Networks. “It reduces [network] latency by 10 to 20 percent,” he says. “This can make a huge difference for financial transactions and for the stock exchange.”

Because of the more complex phase modulation used, 40Gbps DQPSK and DP-QPSK lightpaths when lit alongside 10Gbps suffer from crosstalk interference. “DQPSK is more susceptible to crosstalk but coherent detection is even worse,” says Chris Clarke, vice president strategy and chief engineer at Oclaro.

Wavelength management - using a guard-band channel or two between the 10Gbps and 40Gbps lightpaths – solves the problem. Alcatel-Lucent also claims it has developed a coherent implementation that works alongside existing 10Gbps and 40Gbps DPSK signals without requiring such wavelength management.

100Gbps consensus

Because of the variety of modulation schemes at 40Gbps the industry has sought to achieve a consensus at 100Gbps resulting in coherent becoming the defacto standard.

Early-adopter operators of 40Gbps technology such as AT&T and Verizon Business have been particularly vocal in getting the industry to back DP-QPSK for 100Gbps. The Optical Internetworking Forum (OIF) industry body has also done much work to provide guidelines for the industry as part of its 100Gbps Framework Document.

Yet despite the industry consensus, DP-QPSK will not be the sole modulation scheme targeted at 100Gbps.

ADVA Optical Networking is pursuing 100Gbps technology for the metro and enterprise using a proprietary modulation scheme. “If you look at 100Gbps, we believe there is room for different solutions,” says Elbers.

For metro and enterprise systems, the need is for more compact, less power-consuming, cheaper solutions. ADVA Optical Networking is following a proprietary approach. At ECOC 2008 the company published a paper that combined DPSK with amplitude-shift keying.

“If you look at 100Gbps, we believe there is room for different solutions.”

“If you look at 100Gbps, we believe there is room for different solutions.”

Jörg-Peter Elbers, ADVA Optical Networking

“Coherent DP-QPSK offers the highest performance but it is not required for certain situations as it brings power and cost burdens,” says Elbers. The company plans to release a dedicated product for the metro and enterprise markets and Elbers says the price point will be very close to 10x10Gbps.

Another approach is that of Australian start-up Ofidium. It is using a multi-carrier modulation scheme based on orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing. Ofidium claims that while OFDM is an alternative modulation scheme to DP-QPSK, it uses the same optical building blocks as recommended by the OIF.

Decisions, decisions

Simply looking at the decisions of a small sample of operators highlights the complex considerations involved when deciding a high-speed optical transmission strategy.

Cost is clearly key but is complicated by the various 40Gbps schemes being at different stages of maturity. 40Gbps DPSK is deployed in volume and is now being joined by DQPSK. Coherent technology was, until recently, provided solely by Nortel, now owned by Ciena. However, Nokia Siemens Networks working with CoreOptics, and Fujitsu have recently announced 40Gbps coherent offerings upping the competition.

Ciena also has a first-generation 100Gbps technology and will soon be joined by system vendors either developing their own 100Gbps interfaces or are planning to offer 100Gbps once DP-QPSK transponders become available in 2011.

The particular performance requirements also influence the operators’ choices.

Verizon Business has limited its deployment of DPSK due to the modulation scheme’s tolerance to PMD. “It is quite low, in the 2 to 4 picosecond range,” says Glenn Wellbrock, director of backbone network design at Verizon Business. “We have avoided deploying DPSK even if we have measured the [fibre] route [for PMD].”

Because PMD can degrade over time, even if a route is measured and is within the PMD tolerance there is no guarantee the performance will last. Verizon will deploy DQPSK this year for certain routes due to its higher 8ps tolerance to PMD.

China Telecom is a key proponent of DQPSK for its network rollout of 40Gbps. “It has doubled demand for its 40Gbps build-out and the whole industry is scrambling to keep up,” says Oclaro’s Clarke.

AT&T has deployed DPSK to upgrade its network backbone and will continue as it upgrades its metro and regional networks. “Our stuff [DPSK transponders] is going into [these networks],” says Mintera’s Robinson. But AT&T will use other technologies too.

In general modulation formats are a vendor decision, “something internal to the box”, says King. What is important is their characteristics and how the physics and economics match AT&T’s networks. “As coherent becomes available at 40Gbps, we will be able to offer it where the fibre characteristics require it,” says King.

“AT&T is really hot on DP-QPSK,” says Ron Kline, principal analyst of network infrastructure at Ovum. “They have a whole lot of fibre - stuff before 1998 - that is only good for 2.5Gbps and maybe 10Gbps. They have to be able to use it as it is hard to replace.”

BT points out how having DP-QPSK as the de facto standard for 100Gbps will help make it cost-effective compared to 10Gbps and will also benefit 40Gbps coherent designs. “This offers high performance 40Gbps which will probably work over all of our network,” says Davey.

But this raises another issue regarding coherent: it offers superior performance over long distances yet not all networks need such performance. “For the UK it may be that we simply don’t have sufficient long distance links [to merit DP-QPSK] and so we may as well stick with non-coherent,” says Davey. “In the end pricing and optical reach will determine what is used and where.”

One class of network where reach is supremely important is submarine.

For submarine transmission, reaches between 5,000 and 7,000km can be required and as such 10Gbps links dominate. “In the last six months even if most RFQs (Request for Quotation from operators) are about 10Gbps, all are asking about the possibility of 40Gbps,” says Jose Chesnoy, technical director, submarine network activity at Alcatel-Lucent.

Until now there has also been no capacity improvement in submarine adopting 40Gbps: 10Gbps lightpaths use 25GHz-spaced channels while 40Gbps uses 100GHz. “Now with technology giving 40Gbps performance at 50GHz, fibre capacity is doubled,” says Chesnoy.

To meet trans-ocean distances for 40Gbps submarine, Alcatel-Lucent is backing coherent technology, as it is for terrestrial networks. “Our technology direction is definitely coherent, at 40 and 100Gbps,” says Bucci.

Ciena, with its acquisition of Nortel’s Metro Ethernet Networks division, now offers 40 and 100Gbps coherent technology.

“It’s like asking what the horsepower per cylinder is rather than the horsepower of the engine.”

“It’s like asking what the horsepower per cylinder is rather than the horsepower of the engine.”

Drew Perkins, Infinera

ADVA Optical Networking, unlike Ciena and Alcatel-Lucent, is not developing 40Gbps technology in-house. “When looking at second generation 40Gbps, DQPSK and DP-QPSK are both viable options from a performance point of view,” says Elbers.

He points out that what will determine what ADVA Optical Networking adopts is cost. DQPSK has a higher nonlinear tolerance and can offer lower cost compared to DP-QPSK but there are additional costs besides just the transponder for DQPSK, he says, namely the need for an optical pre-amplifier and an optical tunable dispersion compensator per wavelength.

DP-QPSK, for Elbers, eliminates the need for any optical dispersion compensation and complements 100Gbps DP-QPSK, but is currently a premium technology. “If 40Gbps DP-QPSK is close to the cost of 4x10Gbps tunable XFP [transceivers], it will definitely be used,” he says. “We are not seeing that yet.”

Infinera, with its photonic integrated circuit (PIC) technology, questions the whole premise of debating 40Gbps and 100Gbps technologies. Infinera believes what ultimately matters is how much capacity can be transmitted over a fibre.

“Most people want pure capacity,” says Drew Perkins, Infinera’s CTO, who highlights the limitations of the industry’s focus on line speed rather than overall capacity using the analogy of buying a car. “It’s like asking what the horsepower per cylinder is rather than the horsepower of the engine,” he says.

Infinera offers a 10x10Gbps PIC though it has still not launched its 10x40Gbps DP-DQPSK PIC. “The components have been delivered to the [Infinera] systems group,” says Perkins. The former CEO of Infinera, Jagdeep Singh, has said that while the company is not first to market with 40Gbps it intends to lead the market with the most economical offering.

Moreover, Infinera is planning to develop its own coherent based PIC. “The coherent approach - DP-QPSK ‘Version 1.0’ with a DSP - is very powerful with its high capacity and long reach but it has a significant power density cost,” says Perkins. “We envisage the day when there will be a 10-channel PIC with a 100Gbps coherent-type technology in 50GHz spectrum at very low power.” Such PIC technology would deliver 8 Terabits over a fibre.

Further evidence of the importance of 100Gbps is given by Verizon Business which has announced that it will deploy 100Gbps coherent-optimized fibre links starting next year that will do away with dispersion compensation fibre. AT&T’s King says it will also deploy coherent-optimised links.

Not surprisingly, views also differ among module makers regarding the best 40Gbps modulation schemes to pursue.

“We had a very good look at DQPSK,” says Mintera’s Robinson. “What’s best to invest? The price comparison [DQPSK versus coherent] is very similar yet DP-QPSK is vastly superior [in performance]. Put in a module it will kill off DP-QPSK.”

Finisar has yet to detail its plans but Ward says that the view inside the company is that the lowest cost interface is offered by DPSK while DP-QPSK delivers high performance. “DQPSK is in this challenging position, it can’t meet the cost point of DPSK nor the performance of DP-QPSK,” he says.

Opnext begs to differ.

The firm offers the full spectrum of 40Gbps modulation schemes - optical duobinary, DPSK and DQPSK. “The next phase we are focussed on is 100Gbps coherent,” says Traverso. “We are not as convinced that 40Gbps is a sweet spot.”

In contrast Opnext does believe DQPSK will be popular, although Traverso highlights that it depends on the particular markets being addressed, with DQPSK being particularly suited to regional networks. “One huge advantage of DQPSK is thermal – the coherent IC burns a lot of power”.

Oclaro is also backing DQPSK as the format for metro and regional networks: fibre is typically older and the number of ROADM stages a signal encounters is higher.

Challenges

The maturity of the high–speed transmission supply chain is one challenge facing the industry.

“Many of the critical components are not mature,” says Finisar’s Ward. “There are a lot of small companies - almost start-ups - that are pioneers and are doing amazing things but they are not mature companies.”

JDS Uniphase believes that with the expected growth for 40Gbps and 100Gbps there is an opportunity for the larger optical vendors to play a role. “The economic and technical challenges are still a challenge,” says Tom Fawcett, JDS Uniphase’s director of product line management.

Driving down cost at 40Gbps remains a continuing challenge, agrees Nguyen: “Cost is still an important factor; operators really want lower cost”. To address this the industry is moving along the normal technology evolution path, he says, reducing costs, making designs more compact and enabling the use of techniques such as surface-mount technology.

Mintera has developed a smaller 300-pin MSA DPSK transponder that enable two 40Gbps interfaces on one card: the line side and client side ones. Shown on the right is a traditional 5"x7" 300-pin MSA.

JDS Uniphase’s strategy is to bring the benefits of vertical integration to 40 and 100Gbps; using its own internal components such as its integrated tunable laser assembly, lithium niobate modulator, and know-how to produce an integrated optical receiver to reduce costs and overall power consumption.

Vertical integration is also Oclaro’s strategy with is 40Gbps DQPSK transponder that uses its own tunable laser and integrated indium-phosphide-based transmitter and receiver circuitry.

“[Greater] vertical integration will make our lives more difficult,” says u2t’s Umbach. “But any module maker that has in-house components will only use them if they have the right optical performance.”

Jens Fiedler, vice president sales and marketing at u2t Photonics,stresses that while DQPSK and DP-QPSK may reduce the speed of the photodetectors and hence appear to simplify design requirements, producing integrated balanced receivers is far from trivial. And by supplying multiple customers such as non-vertically integrated module makers and system vendors, merchant firms also have a volume manufacturing advantage.

Opnext has already gone down the vertically integrated path with its portfolio of 40Gbps offerings and is now developing an ASIC for use in its 100Gbps transponders.

Estimates vary that there are between eight and ten companies or partnerships developing their own coherent ASIC. That equates to a total industry spend of some $160 million, leading some to question whether the industry as a whole is being shrewd with its money. “Is that wise use of people’s money?” says Oclaro’s Clarke. “People have got to partner.”

The ASICs are also currently a bottleneck. “For 100Gbps the ASIC is holding everything up,” says Jimmy Yu, a director at the Dell'Oro Group

According to Stefan Rochus, vice president of marketing and business development at CyOptics, another supply challenge is the optical transmitter circuitry at 100Gbps while for 40Gbps DP-QPSK, the main current supplier is Oclaro.

“The [40Gbps] receiver side is well covered,” says Rochus.

CyOptics itself is developing an integrated 40Gbps DPSK balanced receiver that includes a delay-line inteferometer and a balanced receiver. The firm is also developing a 40 and a 100G PM-QPSK receiver, compliant with the OIF Framework Document. This is also a planar lightwave circuit-based design but what is different between 40 and 100Gbps designs is the phodetectors - 10 and 28GHz respectively - and the trans-impedence amplifiers (TIAs).

NeoPhotonics is another optical component company that has announced such integrated DM-QPSK receivers.

And u²t Photonics recently announced a 40G DQPSK dual balanced receiver that it claims reduces board space by 70%, and it has also announced with Picometrix a 100Gbps coherent receiver multi-source agreement.

40 and 100Gbps: next market steps

Verizon Business in late 2009 became the first operator to deploy a 100Gbps route linking Frankfurt and Paris. And the expectation is that only a few more 100Gbps lightpaths will be deployed this year.

The next significant development is the ratification of the 40 and 100 Gigabit Ethernet standards that will happen this year. The advent of such interfaces will spur 40Gbps and 100Gbps line side. After that 100Gbps transponders are expected in mid-2011.

Such transponders will have a two-fold effect: they will enable more system vendors to come to market and reduce the cost of 100Gbps line-side interfaces.

However industry analysts expect the 100Gbps volumes to ramp from 2013 onwards only.

Dell'Oro’s Yu expects the 40Gbps market to grow fiercely all the while 100Gbps technology matures. At 40Gbps he expects DPSK to continue to ship. DP-QPSK will be used for long haul links - greater than 1200km –while DQPSK will find use in the metro. “There is room for all three modulations,” says Yu.

|

40 100G market |

Compound annual growth rate CAGR |

|

Line card volumes |

79% till 2014 |

|

Transponder volumes |

100% till 2015 |

|

Transponder revenues |

65% till 2015 |

Source: Ovum

Ovum and Infonetics have different views regarding the 40Gbps market.

“Coherent is the story; the opportunity for DQPSK being limited,” says Ovum’s Kline. Infonetics’ Schmitt disagrees: “If you were to look back in 2015 over the last five years, the bulk of the deployments [at 40Gbps] will be DQPSK.

Schmitt does agree that 2013 will be a big year for 100Gbps: “100Gbps will ramp faster than 40Gbps but it will not kill it.”

Schmitt foresees operators bundling 10Gbps wavelengths into both 40Gbps and 100Gbps lightpaths (and 10Gbps and 40Gbps lightpaths into 100Gbps ones) using Optical Transport Networking (OTN) encapsulation technology.

Given the timescales, vendors still to make their 40Gbps modulation bets run the risk of being late to market. They are also guaranteed a steep learning curve. Yet those that have made their decisions at 40Gbps will likely remain uncomfortable for a while yet until they can better judge the wisdom of their choices.

For the first part of this feature, click here

For Part 3, click here

Service providers' network planning in need of an overhaul

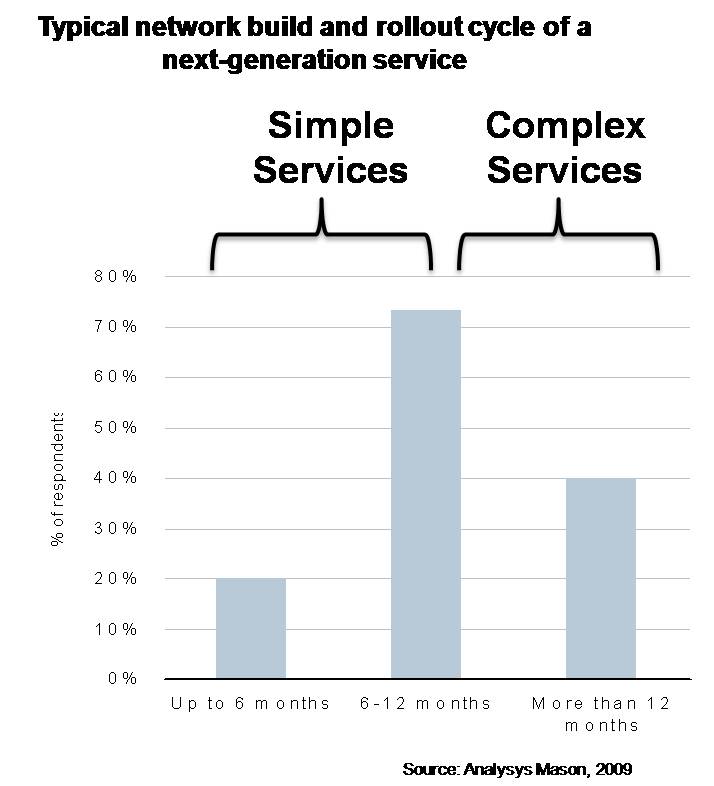

These are the findings of an operator study conducted by Analysys Mason on behalf of Amdocs, the business and operational support systems (BSS/ OSS) vendor.

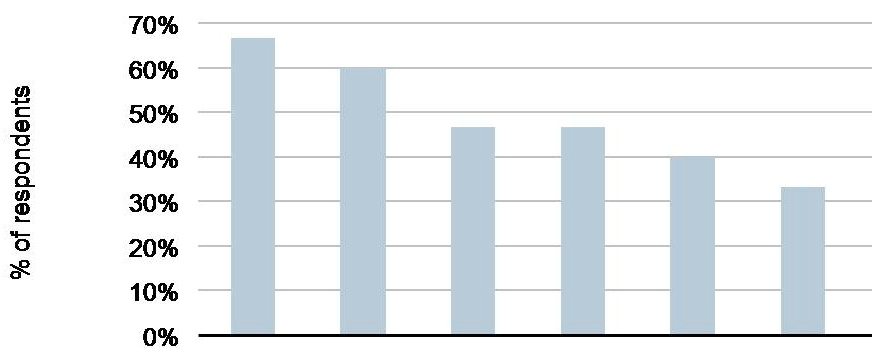

Columns (left to right): 1) Stove-pipe solutions and legacy systems with no time-lined consolidated view 2) Too much time spent on manual processes 3) Too much time (or too little time) and investment on integration efforts with different OSS 4) Lack of consistent processes or tools to roll-out same resources/ technologies 5) Competition difficulties 6) Delays in launching new services. Source: Analysys MasonClick here to view full chart.

Columns (left to right): 1) Stove-pipe solutions and legacy systems with no time-lined consolidated view 2) Too much time spent on manual processes 3) Too much time (or too little time) and investment on integration efforts with different OSS 4) Lack of consistent processes or tools to roll-out same resources/ technologies 5) Competition difficulties 6) Delays in launching new services. Source: Analysys MasonClick here to view full chart.

What is network planning?

Every service provider has a network planning organisation, connected to engineering but a separate unit. According to Mark Mortensen, senior analyst at Analysys Mason and co-author of the study, the unit typically numbers fewer than 100 staff although BT’s, for example, has 600.

"They are highly technical; you will have a ROADM specialist, radio frequency experts, someone knowledgeable on Juniper and Cisco routers," says Mortensen. "Their job is to figure out how to augment the network using the available budget."

In particular, the unit's tasks include strategic planning, doing ‘what-if’ analyses two years ahead to assess likely demand on the network. Technical planning, meanwhile, includes assessing what needs to be bought in the coming year assuming the budget comes in.

The network planners must also address immediate issues such as when an operator wins a contract and must connect an enterprise’s facilities in locations where the operator has no network presence.

“What operators did in two years of planning five years ago they are now doing in a quarter.”

Mark Mortensen, Analysys Mason.

Network planning issues

- Operators have less time to plan. “What operators did in two years of planning five years ago they are now doing in a quarter,” says Mortensen. “BT wants to be able to run a new plan overnight.”

- Automated and sophisticated planning tools do not exist. The small size of the network planning group has meant OSS vendors’ attention has been focused elsewhere.

- If operators could plan forward orders and traffic with greater confidence, they could reduce the amount of extra-capacity they currently have in place. This, according to Mortensen, could save operators 5% of their capital budget.

Key study findings

- Changes in budgets and networks are happening faster than ever before.

- Network planning is becoming more complex requiring the processing of many data inputs. These include how fast network resources are being consumed, by what services and how quickly the services are growing.

- As a result network planning takes longer than the very changes it needs to accommodate. “It [network planning] is a very manual process,” says Mortensen.

- Marketing people now control the budgets. This makes the network planners’ task more complex and requires interaction between the two groups. “This is not a known art and requires compromise,” he says. Mortensen admits that he was surprised by the degree to which the marketing people now control budgets.

In summary

Even if OSS vendors develop sophisticated network planning tools, it is unlikely that end users will notice a difference, says Mortensen. However, it will impact significantly operators’ efficiencies and competitiveness.

Users will also not be as frustrated when new service are launched, such as the poor network performance that resulted due to the huge increases in data generated by the introduction of the latest smartphones. This change may not be evident to users but will be welcome nonetheless.

Study details

Analysys Mason interviewed 24 operators including (40%) mobile, (50%) fixed and (10%) cable. A dozen were Tier One operators while two were Tier Three. The rest - Tier Two operators - are classed as having yearly revenues ranging from US$1bn and 10bn. Lastly, half the operators surveyed were European while the rest were split between Asia Pacific and North America. One Latin American operator was also included.