COBO looks inside and beyond the data centre

The Consortium of On-Board Optics is working on 400 gigabit optics for the data centre and also for longer-distance links. COBO is a Microsoft-led initiative tasked with standardising a form factor for embedded optics.

Established in March 2015, the consortium already has over 50 members and expects to have early specifications next year and first hardware by late 2017.

Brad Booth

Brad Booth

Brad Booth, the chair of COBO and principal architect for Microsoft’s Azure Global Networking Services, says Microsoft plans to deploy 100 gigabit in its data centres next year and that when the company started looking at 400 gigabit, it became concerned about the size of the proposed pluggable modules, and the interface speeds needed between the switch silicon and the pluggable module.

“What jumped out at us is that we might be running into an issue here,” says Booth.

This led Microsoft to create the COBO industry consortium to look at moving optics onto the line card and away from the equipment’s face plate. Such embedded designs are already being used for high-performance computing, says Booth, while data centre switch vendors have done development work using the technology.

On-board optics delivers higher interface densities, and in many cases in the data centre, a pluggable module isn’t required. “We generally know the type of interconnect we are using, it is pretty structured,” says Booth. But the issue with on-board optics is that existing designs are proprietary; no standardised form factor exists.

“It occurred to us that maybe this is the problem that needs to be solved to create better equipment,” says Booth. Can the power consumed between switch silicon and the module be reduced? And can the interface be simplified by eliminating components such as re-timers?

“This is worth doing if you believe that in the long run - not the next five years, but maybe ten years out - optics needs to be really close to the chip, or potentially on-chip,” says Booth.

400 gigabit

COBO sees 400 gigabit as a crunch point. For 100 gigabit interconnect, the market is already well served by various standards and multi-source agreements so it makes no sense for COBO to go head-to-head here. But should COBO prove successful at 400 gigabit, Booth envisages the specification also being used for 100, 50, 25 and even 10 gigabit links, as well as future speeds beyond 400 gigabit.

The consortium is developing standardised footprints for the on-board optics. “If I want to deploy 100 gigabit, that footprint will be common no matter what the reach you are achieving with it,” says Booth. “And if I want a 400 gigabit module, it may be a slightly larger footprint because it has more pins but all the 400 gigabit modules would have a similar footprint.”

COBO plans to use existing interfaces defined by the industry. “We are also looking at other IEEE standards for optical interfaces and various multi-source agreements as necessary,” says Booth. COBO is also technology agnostic; companies will decide which technologies they use to implement the embedded optics for the different speeds and reaches.

“This is worth doing if you believe that in the long run - not the next five years, but maybe ten years out - optics needs to be really close to the chip, or potentially on-chip."

Reliability

Another issue the consortium is focussing on the reliability of on-board optics and whether to use socketed optics or solder the module onto the board. This is an important consideration given that is it is the vendor’s responsibility to fix or replace a card should a module fail.

This has led COBO to analyse the causes of module failure. Largely, it is not the optics but the connections that are the cause. It can be poor alignment with the electrical connector or the cleanliness of the optical connection, whether a pigtail or the connectors linking the embedded module to the face plate. “The discussions are getting to the point where the system reliability is at a level that you have with pluggables, if not better,” says Booth.

Dropping below $1-per-gigabit

COBO expects the cost of its optical interconnect to go below the $1-per-gigabit industry target. “The group will focus on 400 gigabit with the perception that the module could be four modules on 100 gigabit in the same footprint,” says Booth. Using four 100 gigabit optics in one module saves on packaging and the printed circuit board traces needed.

Booth says that 100 gigabit optics is currently priced between $2 and $3-per-gigabit. “If I integrate that into a 400 gigabit module, the price-per-gig comes down significantly” says Booth. “All the stuff I had to replicate four times suddenly is integrated into one, cutting costs significantly in a number of areas.” Significantly enough to dip below the $1-per-gigabit, he says.

Power consumption and line-side optics

COBO has not specified power targets for the embedded optics in part because it has greater control of the thermal environment compared to a pluggable module where the optics is encased in a cage. “By working in the vertical dimension, we can get creative in how we build the heatsink,” says Booth. “We can use the same footprint no matter whether it is 100 gigabit inside or 100 gigabit outside the data centre, the only difference is I’ve got different thermal classifications, a different way to dissipate that power.”

The consortium is investigating whether its embedded optics can support 100 gigabit long-haul optics, given such optics has traditionally been implemented as an embedded design. “Bringing COBO back to that market is extremely powerful because you can better manage the thermal environment,” says Booth. And by removing the power-hungry modules away from the face plate, surface area is freed up that can be used for venting and improving air flow.

“We should be considering everything is possible, although we may not write the specification on Day One,” says Booth. “I’m hoping we may eventually be able to place coherent devices right next to the COBO module or potentially the optics and the coherent device built together.

“If you look at the hyper-scale data centre players, we have guys that focus just as much on inside the data centre as they do on how to connect the data centres in within a metro area, national area and then sub-sea,” says Booth. “That is having an impact because when we start looking at what we want to do with those networks, we want to have some level of control on what we are doing there and on the cost.

“We buy gazillions of optical modules for inside the data centre. Why is it that we have to pay exorbitant prices for the ones that we are not using inside [the data centre],” he says.

“I can’t help paint a more rosier picture because when you have got 1.4 million servers, if I end up with optics down to all of those, that is a lot of interconnect“

Market opportunities

Having a common form factor for on-board optics will allow vendors to focus on what they do best: the optics. “We are buying you for the optics, we are not buying you for the footprint you have on the board,” he says.

Booth is sensitive to the reservations of optical component makers to such internet business-led initiatives. “It is a very tough for these guys to extend themselves to do this type of work because they are putting a lot of their own IP on the line,” says Booth. “This is a very competitive space.”

But he stresses it is also fiercely competitive between the large internet businesses building data centres. “Let’s sit down and figure out what does it take to progress this industry. What does it take to make optics go everywhere?”

Booth also stresses the promising market opportunities COBO can serve such as server interconnect.

“When I look at this market, we are talking about doing optics down to our servers,” says Booth. “I can’t help paint a more rosier picture because when you have got 1.4 million servers, if I end up with optics down to all of those, that is a lot of interconnect.“

ECOC 2015 Review - Part 1

- Several companies announced components for 400 gigabit optical transmission

- NEL announced a 200 gigabit coherent DSP-ASIC

- Lumentum ramps production of its ROADM blades while extending the operating temperature of its tunable SFP+

400 gigabit

Oclaro, Teraxion and NeoPhotonics detailed their latest optical components for 400 gigabit optical transmission using coherent detection.

Oclaro and Teraxion announced 400 gigabit modulators for line-side transmission; Oclaro’s based on lithium niobate and Teraxion’s an indium phosphide one.

NeoPhotonics outlined other components that will be required for higher-speed transmission: indium phosphide-based waveguide photo-detectors for coherent receivers, and ultra-narrow line-width lasers suited for higher order modulation schemes such as dual-polarisation 16-quadrature amplitude modulation (DP-16-QAM) and DP-64-QAM.

There are two common approaches to achieve higher line rates: higher-order modulation schemes such as 16-QAM and 64-QAM, and optics capable of operating at higher signalling rates.

Using 16-QAM doubles the data rate compared to quadrature phase-shift keying (QPSK) modulation that is used at 100 Gig, while 64-QAM doubles the data rate again to 400 gigabit.

Higher-order modulation can use 100 gigabit optics but requires additional signal processing to recover the received data that is inherently closer together. “What this translates to is shorter reaches,” says Ferris Lipscomb, vice president of marketing at NeoPhotonics.

These shorter distances can serve data centre interconnect and metro applications where distances range from sub-100 kilometers to several hundred kilometers. But such schemes do not work for long haul where sensitivity to noise is too great, says Lipscomb.

What we are seeing from our customers and from carriers looking at next-generation wavelength-division multiplexing systems for long haul is that they are starting to design their systems and are getting ready for 400 Gig

Lipscomb highlights the company’s dual integrable tunable laser assembly (iTLAs) with its 50kHz narrow line-width. “That becomes very important for higher-order modulation because the different states are closer together; any phase noise can really hurt the optical signal-to-noise ratio,” he says

The second approach to boost transmission speed is to increase the signalling rate. “Instead of each stream at 32 gigabaud, the next phase will be 42 or 64 gigabaud and we have receivers that can handle those speeds,” says Lipscomb. The use of 42 gigabaud can be seen as an intermediate step to a higher line rate - 300 gigabit – while being less demanding on the optics and electronics than a doubling to 64 gigabaud.

Oclaro’s lithium niobate modulator supports 64 gigabaud. “We have increased the bandwidth beyond 35 GHz with a good spectral response – we don’t have ripples – and we have increased the modulator’s extinction ratio which is important at 16-QAM,” says Robert Blum, Oclaro’s director of strategic marketing.

We have already demonstrated a 400 Gig single-wavelength transmission over 500km using DP-16-QAM and 56 gigabaud

Indium phosphide is now coming to market and will eventually replace lithium niobate because of the advantages of cost and size, says Blum, but lithium niobate continues to lead the way for highest speed, long-reach applications. Oclaro has been delivering its lithium niobate modulator since the third quarter of the year.

Teraxion offers an indium phosphide modulator suited to 400 gigabit. “One of the key differentiators of our modulator is that we have a very high bandwidth such that single-wavelength transmission at 400 Gig is possible,” says Martin Guy, CTO and strategic marketing at Teraxion. “We have already demonstrated a 400 Gig single-wavelength transmission over 500km using DP-16-QAM and 56 gigabaud.”

“What we are seeing from our customers and from carriers looking at next-generation wavelength-division multiplexing systems for long haul is that they are starting to design their systems and are getting ready for 400 Gig,” says Blum.

Teraxion says it is seeing a lot of activity regarding single-wavelength 400 Gig transmission. “We have sampled product to many customers,” says Guy.

NeoPhotonics says the move to higher baud rates is still some way off with regard systems shipments, but that is what people are pursuing for long haul and metro regional.

200 Gig DSP-ASIC

Another key component that will be needed for systems operating at higher transmission speeds is more powerful coherent digital signal processors (DSPs). NTT Electronics (NEL) announced at ECOC that it is now shipping samples of its 200 gigabit DSP-ASIC, implemented using a 20nm CMOS process.

Dubbed the NLD0660, the DSP features a new core that uses soft-decision forward error correction (SD-FEC) that achieves a 12dB net coding gain. Improving the coding gain allows greater spans before optical regeneration or longer overall reach, says NEL. The DSP-ASIC supports several modulation formats: DP-QPSK, DP-8-QAM and DP-16-QAM, for 100 Gig, 150 Gig and 200 Gig rates, respectively. Using two NLD0660s, 400 gigabit coherent transmission is achieved.

NEL announced its first 20nm DSP-ASIC, the lower-power 100 gigabit NLD0640 at OFC 2015 in March. At the same event, ClariPhy demonstrated its own merchant 200 gigabit DSP-ASIC.

Reconfigurable optical add/ drop multiplexers

Lumentum gave an update on its TrueFlex route & select architecture Super Transport Blade, saying it has now been qualified, with custom versions of the line card being manufactured for equipment makers. The Super Transport Blades will be used in next-generation ROADMs for 100 gigabit metro deployments. The Super Transport Blade supports flexible grid, colourless, directionless and contentionless ROADM designs.

“This is the release of the full ROADM degree for next-generation networks, all in a one-slot line card,” says Brandon Collings, CTO of Lumentum. “It is a pretty big milestone; we have been talking about it for years.”

Collings says that the cards are customised to meet an equipment maker’s particular requirements. “But they are generally similar in their core configuration; they all use twin wavelength-selective switches (WSSes), those sort of building blocks.”

This is the release of the full ROADM degree for next-generation networks, all in a one-slot line card. It is a pretty big milestone; we have been talking about it for years

Lumentum also announced 4x4 and 6x6 integrated isolator arrays. “If you look at those ROADMs, there is a huge number of connections inside,” says Collings. The WSSes can be 1x20 and two can be used - a large number of fibres - and at certain points isolators are required. “Using discrete isolators and needing a large number, it becomes quite cumbersome and costly, so we developed a way to connect four or six isolators in a single package,” he says.

A 6x6 isolator array is a six-lane device with six hardwired input/ output pairs, with each input/ output pair having an isolator between them. “It sounds trivial but when you get to that scale, it is truly enabling,” says Collings.

Isolators are needed to keep light from going in the wrong direction. “These things can start to accumulate and can be disruptive just because of the sheer volume of connections that are present,” says Collings.

Tunable transceivers

Lumentum offers a tunable SFP+ module that consumes less than 1.5W while operating over a temperature range of -5C to +70C. At ECOC, the company announced that in early 2016 it will release a tunable SFP+ with an extended temperature range of -5C to +85C.

Further information

Heading off the capacity crunch, click here

For the ECOC Review, Part 1, click here

OFC 2015 digest: Part 2

- CFP4- and QSFP28-based 100GBASE-LR4 announced

- First mid-reach optics in the QSFP28

- SFP extended to 28 Gigabit

- 400 Gig precursors using DMT and PAM-4 modulations

- VCSEL roadmap promises higher speeds and greater reach

Acacia unveils 400 Gigabit coherent transceiver

- The AC-400 5x7 inch MSA transceiver is a dual-carrier design

- Modulation formats supported include PM-QPSK, PM-8-QAM and PM-16-QAM

- Acacia’s DSP-ASIC is a 1.3 billion transistor dual-core chip

Acacia Communications has unveiled the industry's first flexible rate transceiver in a 5x7-inch MSA form factor that is capable of up to 400 Gigabit transmission rates. The company made the announcement at the OFC show held in Los Angeles.

Dubbed the AC-400, the transceiver supports 200, 300 and 400 Gigabit rates and includes two silicon photonics chips, each implementing single-carrier optical transmission, and a coherent DSP-ASIC. Acacia designs its own silicon photonics and DSP-ASIC ICs.

"The ASIC continues to drive performance while the optics continues to drive cost leadership," says Raj Shanmugaraj, Acacia's president and CEO.

The AC-400 uses several modulation formats that offer various capacity-reach options. The dual-carrier transceiver supports 200 Gig using polarisation multiplexing, quadrature phase-shift keying (PM-QPSK) and 400 Gig using 16-quadrature amplitude modulation (PM-16-QAM). The 16-QAM option is used primarily for data centre interconnect for distances up to a few hundred kilometers, says Benny Mikkelsen, co-founder and CTO of Acacia: "16-QAM provides the lowest cost-per-bit but goes shorter distances than QPSK."

Acacia has also implemented a third, intermediate format - PM-8-QAM - that improves reach compared to 16-QAM but encodes three bits per symbol (a total of 300 Gig) instead of 16-QAM's four bits (400 Gig). "8-QAM is a great compromise between 16-QAM and QPSK," says Mikkelsen. "It supports regional and even long-haul distances but with 50 percent higher capacity than QPSK." Acacia says one of its customer will use PM-8-QAM for a 10,000 km submarine cable application.

Source: Gazettabyte

Source: Gazettabyte

Other AC-400 transceiver features include OTN framing and forward error correction. The OTN framing can carry 100 Gigabit Ethernet and OTU4 signals as well as the newer OTUc1 format that allows client signals to be synchronised such that a 400 Gigabit flow from a router port can be carried, for example. The FEC options include a 15 percent overhead code for metro and a 25 percent overhead code for submarine applications.

The 28 nm CMOS DSP-ASIC features two cores to process the dual-carrier signals. According to Acacia, its customers claim the DSP-ASIC has a power consumption less than half that of its competitors. The ASIC used for Acacia’s AC-100 CFP pluggable transceiver announced a year ago consumes 12-15W and is the basis of its latest DSP design, suggesting an overall power consumption of 25 to 30+ Watts. Acacia has not provided power consumption figures and points out that since the device implements multiple modes, the power consumption varies.

The AC-400 uses two silicon photonics chips, one for each carrier. The design, Acacia's second generation photonic integrated circuit (PIC), has a reduced insertion loss such that it can now achieve submarine transmission reaches. "Its performance is on a par with lithium niobate [modulators]," says Mikkelsen.

It has been surprising to us, and probably even more surprising to our customers, how well silicon photonics is performing

The PIC’s basic optical building blocks - the modulators and the photo-detectors - have not been changed from the first-generation design. What has been improved is how light enters and exits the PIC, thereby reducing the coupling loss. The latest PIC has the same pin-out and fits in the same gold box as the first-generation design. "It has been surprising to us, and probably even more surprising to our customers, how well silicon photonics is performing," says Mikkelsen.

Acacia has not tried to integrate the two wavelength circuits on one PIC. "At this point we don't see a lot of cost savings doing that," says Mikkelsen. "Will we do that at some point in future? I don't know." Since there needs to be an ASIC associated with each channel, there is little benefit in having a highly integrated PIC followed by several discrete DSP-ASICs, one per channel.

The start-up now offers several optical module products. Its original 5x7 inch AC-100 MSA for long-haul applications is used by over 10 customers, while it has two 5x7 inch modules for submarine operating at 40 Gig and 100 Gig are used by two of the largest submarine network operators. Its more recent AC-100 CFP has been adopted by over 15 customers. These include most of the tier 1 carriers, says Acacia, and some content service providers. The AC-100 CFP has also been demonstrated working with Fujitsu Optical Components's CFP that uses NTT Electronics's DSP-ASIC. Acacia expects to ship 15,000 AC-100 coherent CFPs this year.

Each of the company's module products uses a custom DSP-ASIC such that Acacia has designed five coherent modems in as many years. "This is how we believe we out-compete the competition," says Shanmugaraj.

Meanwhile, Acacia’s coherent AC-400 MSA module is now sampling and will be generally available in the second quarter.

OIF shows 56G electrical interfaces & CFP2-ACO

“The most important thing for everyone is power consumption on the line card”

“The most important thing for everyone is power consumption on the line card”

The OIF - an industry organisation comprising communications service providers, internet content providers, system vendors and component companies - is developing the next common electrical interface (CEI) specifications. The OIF is also continuing to advance fixed and pluggable optical module specifications for coherent transmission including the pluggable CFP2 (CFP2-ACO).

“These are major milestones that the [demonstration] efforts are even taking place,” says Nathan Tracy, a technologist at TE Connectivity and the OIF technical committee chair.

Tracy stresses that the CEI-56G specifications and the CFP2-ACO remain works in progress. “They are not completed documents, and what the demonstrations are not showing are compliance and interoperability,” he says.

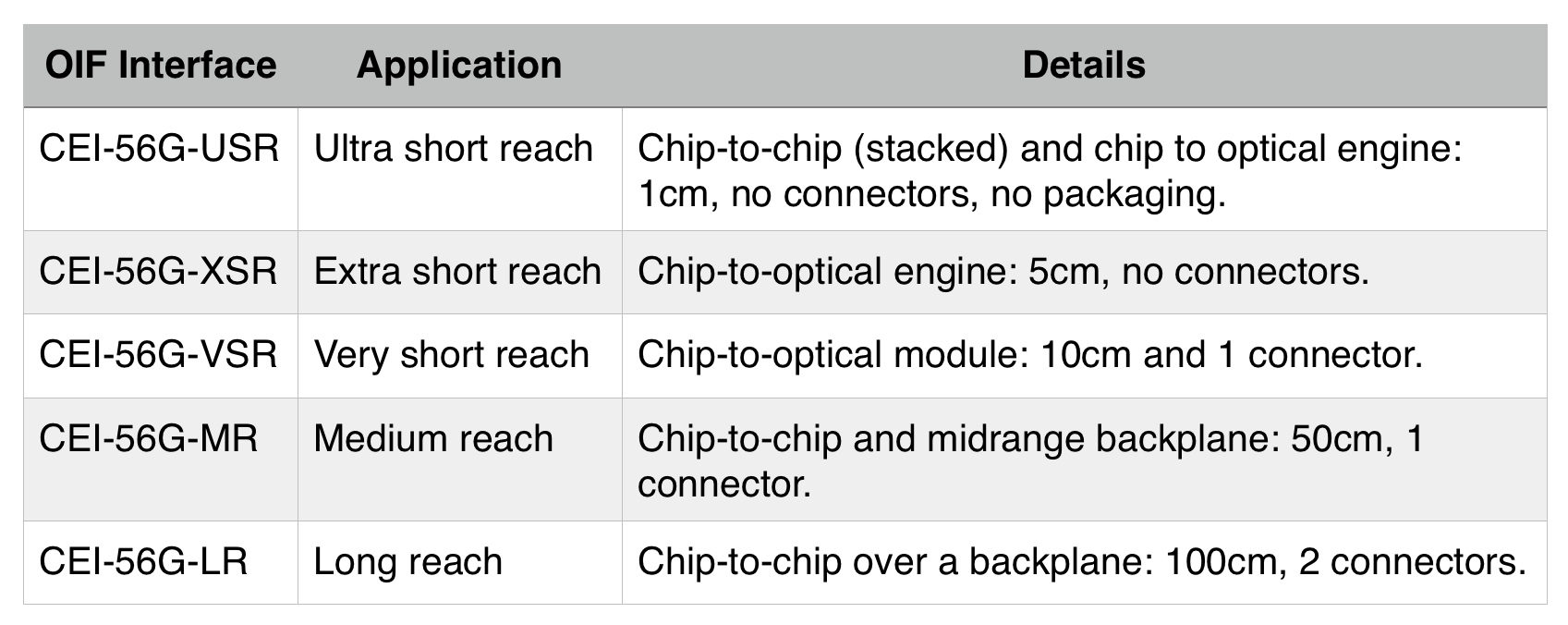

Five CEI-56G specifications are under development, such as platform backplanes and links between a chip and an optical engine on a line card (see Table below).

Moving from the current 28 Gig electrical interface specifications to 56 Gig promises to double the interface capacity and cut electrical interface widths by half. “If we were going to do 400 Gigabit with 25 Gig channels, we would need 16 channels,” says Tracy. “If we can do 50 Gig, we can get it down to eight channels.” Such a development will enable chassis to carry more traffic and help address the continual demand for more bandwidth, he says.

But doubling the data rate is challenging. “As we double the rate, the electrical loss or attenuation of the signal travelling across a printed circuit board is significantly impacted,” says Tracy. “So now our reaches have to get a lot shorter, or the silicon that sends and receives has to improve to significant higher levels.”

One of the biggest challenges in system design is thermal management

Moreover, chip designers must ensure that the power consumption of their silicon do not rise. “We have to be careful as to what the market will tolerate, as one of the biggest challenges in system design is thermal management,” says Tracy. “We can’t just do what it takes to get to 56 Gigabit.”

To this aim, the OIF is pursuing two parallel tracks: using 56 Gigabit non-return-to-zero (NRZ) signalling and 4-level pulse amplitude modulation (PAM-4) which encodes two bits per symbol such that a 28 Gbaud signalling rate can be used. The 56 Gig NRZ uses simpler signalling but must deal with the higher associated loss, while PAM-4 does not suffer the same loss as it is similar to existing CEI-28 channels used today but requires a more complex design.

“Some [of the five CEI-56G specifications] use NRZ, some PAM-4 and some both,” says Tracy. The OIF will not say when it will complete the CEI-56G specifications. However, the projects are making similar progress while the OIF is increasing its interactions with other industry standards groups to shorten the overall timeline.

Source: OIF, Gazettabyte

Source: OIF, Gazettabyte

Two of the CEI-56G specifications cover much shorter distances: the Extra Short Reach (XSR) and Ultra Short Reach (USR). According to the OIF, in the past it was unclear that the industry would benefit from interoperability for such short reaches.

“What is different at 56 Gig is that architectures are fundamentally being changed: higher data rates, industry demand for higher levels of performance, and changing fabrication technologies,” says Tracy. Such fabrication technologies include 3D packaging and multi-chip modules (MCMs) where silicon dies from different chip vendors may be connected within the module.

The XSR interface is designed to enable higher aggregate bandwidth on a line card which is becoming limited by the number of pluggable modules that can be fitted on the platform’s face plate. Density can be increased by using mid-board optics (an optical engine) placed closer to a chip. Here, fibre from the optical engine is fed to the front plate increasing the overall interface capacity.

The USR interface is to support stackable ICs and MCMs.

All are coming together in this pre-competitive stage to define the specifications, yet, at the same time, we are all fierce competitors

“The most important thing for everyone is power consumption on the line card,” says Tracy. “If you define these very short reach interfaces in such a way that these chips do not need as much power, then we have helped to enable the next generation of line card.”

The live demonstrations at OFC include a CEI-56G-VSR-NRZ channel, a CEI-56G-VSR-PAM QSFP compliance board, CEI-56G-MR/LR-PAM and CEI-56G-MR/LR-NRZ backplanes, and a CEI-56G-MR-NRZ passive copper cable.

The demonstrations reflects what OIF members are willing to show, as some companies prefer to keep their work private. “All are coming together in this pre-competitive stage to define the specifications, yet, at the same time, we are all fierce competitors,” says Tracy.

CFP2-ACO

Also on display is working CFP2 analogue coherent optics (CFP2-ACO). The significance of coherent optics in a pluggable CFP2 is the promise of higher-density line cards. The CFP is a much bigger module and at most four can be fitted on a line card, while with the smaller CFP2, with its lower power consumption, up to eight modules are possible.

Using the CFP2-ACO, the coherent DSP-ASIC is external to the CFP2 module. Much work has been done to ensure that the electrical interface can support the analogue signalling between the CFP2 optics and the on-board DSP-ASIC, says Tracy.

At OFC, several companies have unveiled their CFP2-ACO products including Finisar, Fujitsu Optical Components, Oclaro and NEC, while Clariphy has announced a single-board reference design that includes its CL20010 DSP-ASIC and a CFP2-ACO slot.

ECOC reflections: final part

Gazettabyte asked several attendees at the recent ECOC show, held in Cannes, to comment on key developments and trends they noted, as well as the issues they will track in the coming year.

Dr. Ioannis Tomkos, Fellow of OSA & Fellow of IET, Athens Information Technology Center (AIT)

With ECOC 2014 celebrating its 40th anniversary, the technical programme committee did its best to mark the occasion. For example, at the anniversary symposium, notable speakers presented the history of optical communications. Actual breakthroughs discussed during the conference sessions were limited, however.

Ioannis Tomkos

Ioannis Tomkos

It appears that after 2008 to 2012, a period of significant advancements, the industry is now more mainstream, and significant shifts in technologies are limited. It is clear that the original focus four decades ago on novel photonics technologies is long gone. Instead, there is more and more of a focus on high-speed electronics, signal processing algorithms, and networking. These have little to do with photonics even if they greatly improve the overall efficient operation of optical communication systems and networks.

Coherent detection technology is making its way in metro with commercial offerings becoming available, while in academia it is also discussed as a possible solution for future access network applications where long-reach, very-high power budgets and high-bit rates per customer are required. However, this will only happen if someone can come up with cost-effective implementations.

Advanced modulation formats and the associated digital signal processing are now well established for ultra-high capacity spectral-efficient transmission. The focus in now on forward-error-correction codes and their efficient implementations to deliver the required differentiation and competitive advantage of one offering versus another. This explains why so many of the relevant sessions and talks were so well attended.

There were several dedicated sessions covering flexible/ elastic optical networking. It was also mentioned in the plenary session by operator Orange. It looks like a field that started only fives years ago is maturing and people are now convinced about the significant short-term commercial potential of related solutions. Regarding latest research efforts in this field, people have realised that flexible networking using spectral super-channels will offer the most benefit if it becomes possible to access the contents of the super-channels at intermediate network locations/ nodes. To achieve that, besides traditional traffic grooming approaches such as those based on OTN, there were also several ground-breaking presentations proposing all-optical techniques to add/ drop sub-channels out of the super-channel.

Progress made so far on long-haul high-capacity space-division-multiplexed systems, as reported in a tutorial, invited talks and some contributed presentations, is amazing, yet the potential for wide-scale deployment of such technology was discussed by many as being at least a decade away. Certainly, this research generates a lot of interesting know-how but the impact in the industry might come with a long delay, after flexible networking and terabit transmission becomes mainstream.

Much attention was also given at ECOC to the application of optical communications in data centre networks, from data-centre interconnection to chip-to-chip links. There were many dedicated sessions and all were well attended.

Besides short-term work on high-bit-rate transceivers, there is also much effort towards novel silicon photonic integration approaches for realising optical interconnects, space-division-multiplexing approaches that for sure will first find their way in data centres, and even efforts related with the application of optical switching in data centres.

At the networking sessions, the buzz was around software-defined networking (SDN) and network functions virtualisation (NFV) now at the top of the “hype-cycle”. Both technologies have great potential to disrupt the industry structure, but scientific breakthroughs are obviously limited.

As for my interests going forward, I intend to look for more developments in the field of mobile traffic front-haul/ back-haul for the emerging 5G networks, as well as optical networking solutions for data centres since I feel that both markets present significant growth opportunities for the optical communications/ networking industry and the ECOC scientific community.

Dr. Jörg-Peter Elbers, vice president advanced technology, CTO Office, ADVA Optical Networking

The top topics at ECOC 2014 for me were elastic networks covering flexible grid, super-channels and selectable higher-order modulation; transport SDN; 100-Gigabit-plus data centre interconnects; mobile back- and front-hauling; and next-generation access networks.

For elastic networks, an optical layer with a flexible wavelength grid has become the de-facto standard. Investigations on the transceiver side are not just focussed on increasing the spectral efficiency, but also at increasing the symbol rate as a prospect for lowering the number of carriers for 400-Gigabit-plus super-channels and cost while maintaining the reach.

Jörg-Peter Elbers

Jörg-Peter Elbers

As we approach the Shannon limit, spectral efficiency gains are becoming limited. More papers were focussed on multi-core and/or few-mode fibres as a way to increase fibre capacity.

Transport SDN work is focussing on multi-tenancy network operation and multi-layer/ multi-domain network optimisation as the main use cases. Due to a lack of a standard for north-bound interfaces and a commonly agreed information model, many published papers are relying on vendor-specific implementations and proprietary protocol extensions.

Direct detect technologies for 400 Gigabit data centre interconnects are a hot topic in the IEEE and the industry. Consequently, there were a multitude of presentations, discussions and demonstrations on this topic with non-return-to-zero (NRZ), pulse amplitude modulation (PAM) and discrete multi-tone (DMT) being considered as the main modulation options. 100 Gigabit per wavelength is a desirable target for 400 Gig interconnects, to limit the overall number of parallel wavelengths. The obtainable optical performance on long links, specifically between geographically-dispersed data centres, though, may require staying at 50 Gig wavelengths.

In mobile back- and front-hauling, people increasingly recognise the timing challenges associated with LTE-Advanced networks and are looking for WDM-based networks as solutions. In the next-generation access space, components and solutions around NG-PON2 and its evolution gained most interest. Low-cost tunable lasers are a prerequisite and several companies are working on such solutions with some of them presenting results at the conference.

Questions around the use of SDN and NFV in optical networks beyond transport SDN point to the access and aggregation networks as a primary application area. The capability to programme the forwarding behaviour of the networks, and place and chain software network functions where they best fit, is seen as a way of lowering operational costs, increasing network efficiency and providing service agility and elasticity.

What did I learn at the show/ conference? There is a lot of development in optical components, leading to innovation cycles not always compatible with those of routers and switches. In turn, the cost, density and power consumption of short-reach interconnects is continually improving and these performance metrics are all lower than what can be achieved with line interfaces. This raises the question whether separating the photonic layer equipment from the electronic switching and routing equipment is not a better approach than building integrated multi-layer god-boxes.

There were no notable new trends or surprises at ECOC this year. Most of the presented work continued and elaborated on topics already identified.

As for what we will track closely in the coming year, all of the above developments are of interesting. Inter-data centre connectivity, WDM-PON and open programmable optical core networks are three to mention in particular.

For the first ECOC reflections, click here

Ranovus readies its interfaces for deployment

- Products will be deployed in the first half of 2015

- Ranovus has raised US $24 million in a second funding round

- The start-up is a co-founder of the OpenOptics MSA; Oracle is now also an MSA member.

Ranovus says its interconnect products will be deployed in the first half of 2015. The start-up, which is developing WDM-based interfaces for use in and between data centres, has raised US $24 million in a second stage funding round. The company first raised $11 million in September 2013.

Saeid Aramideh"There is a lot of excitement around technologies being developed for the data centre," says Saeid Aramideh, a Ranovus co-founder and chief marketing and sales officer. He highlights such technologies as switch ICs, software-defined networking (SDN), and components that deliver cost savings and power-consumption reductions. "Definitely, there is a lot of money available if you have the right team and value proposition," says Aramideh. "Not just in Silicon Valley is there interest, but in Canada and the EU."

Saeid Aramideh"There is a lot of excitement around technologies being developed for the data centre," says Saeid Aramideh, a Ranovus co-founder and chief marketing and sales officer. He highlights such technologies as switch ICs, software-defined networking (SDN), and components that deliver cost savings and power-consumption reductions. "Definitely, there is a lot of money available if you have the right team and value proposition," says Aramideh. "Not just in Silicon Valley is there interest, but in Canada and the EU."

The optical start-up's core technology is a quantum dot multi-wavelength laser which it is combining with silicon photonics and electronics to create WDM-based optical engines. With the laser, a single gain block provides several channels while Ranovus is using a ring resonator implemented in silicon photonics for modulation. The company is also designing the electronics that accompanies the optics.

Aramideh says the use of silicon photonics is a key part of the design. "How do you enable cost-effective WDM?" he says."It is not possible without silicon photonics." The right cost points for key components such as the modulator can be achieved using the technology. "It would be ten times the cost if you didn't do it with silicon photonics," he says.

The firm has been working with several large internet content providers to turn its core technology into products. "We have partnered with leading data centre operators to make sure we develop the right products for what these folks are looking for," says Aramideh.

In the last year, the start-up has been developing variants of its laser technology - in terms of line width and output power - for the products it is planning. "A lot goes into getting a laser qualified," says Aramideh. The company has also opened a site in Nuremberg alongside its headquarters in Ottawa and its Silicon Valley office. The latest capital will be used to ready the company's technology for manufacturing and recruit more R&D staff, particularly at its Nuremberg site.

Ranovus is a founding member, along with Mellanox, of the 100 Gigabit OpenOptics multi-source agreement. Oracle, Vertilas and Ghiasi Quantum have since joined the MSA. The 4x25 Gig OpenOptics MSA has a reach of 2km-plus and will be implemented using a QSFP28 optical module. OpenOptics differs from the other mid-reach interfaces - the CWDM4, PSM4 and the CLR4 - in that it uses lasers at 1550nm and is dense wavelength-division multiplexed (DWDM) based.

It is never good that an industry is fragmented

That there are as many as four competing mid-reach optical module developments, is that not a concern? "It is never good that an industry is fragmented," says Aramideh. He also dismisses a concern that the other MSAs have established large optical module manufacturers as members whereas OpenOptics does not.

"We ran a module company [in the past - CoreOptics]; we have delivered module solutions to various OEMs that are running is some of the largest networks deployed today," says Aramideh. "Mellanox [the other MSA co-founder] is also a very capable solution provider."

Ranovus plans to use contract manufacturers in Asia Pacific to make its products, the same contract manufacturers the leading optical module makers use.

Table 1: The OpenOptics MSA

Table 1: The OpenOptics MSA

End markets

"I don't think as a business, anyone can ignore the big players upgrading data centres," says Aramideh. "The likes of Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple and others that are switching from a three-tier architecture to a leaf and spine need longer-reach connectivity and much higher capacity." The capacity requirements are much beyond 10 Gig and 40 Gig, and even 100 Gig, he says.

Ranovus segments the adopters of interconnect into two: the mass market and the technology adopters. "Mass adoption today is all MSA-based," says Aramideh. "The -LR4 and -SR10, and the same thing is happening at 100 Gig with the QSFP28." The challenge for the optical module companies is who has the lowest cost.

Then there are the industry leaders such as the large internet content providers that want innovative products that address their needs now. "They are less concerned about multi-source standard-based solutions if you can show them you can deliver a product they need at the right cost," says Aramideh.

Ranovus will offer an optical engine as well as the QSFP28 optical module. "The notion of the integration of an optical engine with switch ICs and other piece parts in the data centre are more of an urgent need," he says.

Using WDM technology, the company has a scalable roadmap that includes 8x25 Gig and 16x25 Gig (400 Gig) designs. Also, by adding higher-order modulation, the technology will scale to 1.6 Terabit (16x100 Gig), says Aramideh.

I don't see a roadmap for coherent to become cost-effective to address the smaller distances

Ranovus is also working on interfaces to link data centres.

"These are distances much shorter than metro/ regional networks," says Aramideh, with the bulk of the requirements being for links of 15 to 40km. For such relatively short distances, coherent detection technology has a high-power consumption and is expensive. "I don't see a roadmap for coherent to become cost-effective to address the smaller distances," says Aramideh.

Instead, the company believes that a direct-detection interconnect that supports 15 to 40km and which has a spectral efficiency that can scale to 9.6 Terabit is the right way to go. If that can be achieved, then switching from coherent to direct detection becomes a no-brainer, he says. "For inter-data-centres, we are really offering an alternative to coherent."

The start-up says its technology will be in product deployment with lead customers in the first half of 2015.

First silicon photonics devices from STMicro in 2014

STMicroelectronics expects to have first silicon photonics products by mid-2014. The chip company announced the licensing of silicon photonics technology from Luxtera in March 2012. Since then STMicro has been developing its 300mm (12-inch) CMOS wafer manufacturing line for silicon photonics at its fab at Crolles, France.

Flavio Benetti, STMicroelectronics

Flavio Benetti, STMicroelectronics

"We think we are the only ones doing the processing in a 12-inch line," says Flavio Benetti, general manager of mixed processes division at STMicroelectronics.

The company has a manufacturing agreement with Luxtera and the two continue to collaborate. "We have all the seeds to have a long-term collaboration," says Benetti.

"We also have the freedom to develop our own products." STMicro has long supplied CMOS and BiCMOS ICs to optical module makers, and will make the ICs and its photonic circuits separately.

The company's interest in silicon photonics is due to the growth in data rates and the need of its customers to have more advanced solutions at 100 Gig and 400 Gig in future.

"It is evident that traditional electronics circuits for that are showing their limits in terms of speed, reach and power consumption," says Benetti. "So we have been doing our due diligence in the market, and silicon photonics is one of the possible solutions."

It is evident that traditional electronics circuits for that are showing their limits in terms of speed, reach and power consumption

The chip company will need to fill its 300mm production line and is eyeing short-reach interconnect used in the data centre. STMicro is open to the idea of offering a foundry service to other companies in future but this is not its current strategy, says Benetti: "A foundry model is not excluded in the long term - business is business - but we are not going to release the technology to the open market as a wafer foundry."

The photonic circuits will be made using a 65nm lithography line, chosen as it offers a good tradeoff between manufacturing cost and device feature precision. Test wafers have already been run through the manufacturing line. "Being the first time we put an optical process in a CMOS line, we are very satisfied with the progress," says Benetti.

One challenge with silicon photonics is the ability to get the light in and out of the circuit. "There you have some elements like the gratings couplers - the shape of the grating couplers and the degree of precision are fundamental for the efficiency of the light coupling," says Benetti. "If you use a 90nm CMOS process, it may cost less but 65nm is a good compromise between cost and technical performance." The resulting photonic device and the electronics IC are bonded in a 3D structure and are interfaced using copper pillars.

A foundry model is not excluded in the long term - business is business - but we are not going to release the technology to the open market as a wafer foundry

Making the electronics and photonic chips separately has performance benefits and is more economical: the dedicated photonic circuit is optimised for photonics and there are fewer masks or extra processing layers compared to making an electro-optic, monolithic chip. The customer also has more freedom in the choice of the companion chip - whether to use a CMOS or BiCMOS process. Also some STMicro customers already have a electronic IC that they can reuse. Lastly, says Benetti, customers can upgrade the electronics IC without touching the photonic circuit.

Benetti is already seeing interest from equipment makers to use such silicon photonics designs directly, bypassing the optical module makers. Will such a development simplify the traditional optical supply chain? "There is truth in that; we see that," says Benetti. But he is wary of predicting disruptive change to the traditional supply chain. "System vendors understand the issue of the supply chain with the added margins [at each production stage] but to simplify that, I'm not so sure it is an easy job," he says.

Benetti also highlights the progress being made with silicon photonics circuit design tools.

STMicro's test circuits currently in the fab have been developed using electronic design automation (EDA) tools. "Already the first generation design kit is rather complete - not only the physical design tools for the optics and electronics but also the ability to simulate the system [the two together] with the EDA tools," says Benetti.

But challenges remain.

One is the ability to get light in and out of the chip in an industrial way. "Coupling the light in the fibre attachment - these are processes that still have a high degree of improvement," says Benetti. "The process of the fibre attachment and the packaging is something we are working a lot on. We have today at a very good stage of speed and precision in the placement of the fibres but there is still much we can do."

Merits and challenges of optical transmission at 64 Gbaud

u2t Photonics announced recently a balanced detector that supports 64Gbaud. This promises coherent transmission systems with double the data rate. But even if the remaining components - the modulator and DSP-ASIC capable of operating at 64Gbaud - were available, would such an approach make sense?

Gazettabyte asked system vendors Transmode and Ciena for their views.

Transmode:

Transmode points out that 100 Gigabit dual-polarisation, quadrature phase-shift keying (DP-QPSK) using coherent detection has several attractive characteristics as a modulation format.

It can be used in the same grid as 10 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) and 40Gbps signals in the C-band. It also has a similar reach as 10Gbps by achieving a comparable optical signal-to-noise ratio (OSNR). Moreover, it has superior tolerance to chromatic dispersion and polarisation mode dispersion (PMD), enabling easier network design, especially with meshed networking.

The IEEE has started work standardising the follow-on speed of 400 Gigabit. "This is a reasonable step since it will be possible to design optical transmission systems at 400 Gig with reasonable performance and cost," says Ulf Persson, director of network architecture in Transmode's CTO office.

Moving to 100Gbps was a large technology jump that involved advanced technologies such as high-speed analogue-to-digital (A/D) converters and advanced digital signal processing, says Transmode. But it kept the complexity within the optical transceivers which could be used with current optical networks. It also enabled new network designs due to the advanced chromatic dispersion and PMD compensations made possible by the coherent technology and the DSP-ASIC.

For 400Gbps, the transition will be simpler. "Going from 100 Gig to 400 Gig will re-use a lot of the technologies used for 100 Gig coherent," says Magnus Olson, director of hardware engineering.

So even if there will be some challenges with higher-speed components, the main challenge will move from the optical transceivers to the network, he says. That is because whatever modulation format is selected for 400Gbps, it will not be possible to fit that signal into current networks keeping both the current channel plan and the reach.

"From an industry point of view, a metro-centric cost reduction of 100Gbps coherent is currently more important than increasing the bit rate to 400Gbps"

"If you choose a 400 Gigabit single carrier modulation format that fits into a 50 Gig channel spacing, the optical performance will be rather poor, resulting in shorter transmission distances," says Persson. Choosing a modulation format that has a reasonable optical performance will require a wider passband. Inevitably there will be a tradeoff between these two parameters, he says.

This will likely lead to different modulation formats being used at 400 Gig, depending on the network application targeted. Several modulation formats are being investigated, says Transmode, but the two most discussed are:

- 4x100Gbps super-channels modulated with DP-QPSK. This is the same as today's modulation format with the same optical performance as 100Gbps, and requires a channel width of 150GHz.

- 2x200Gbps super-channels, modulated with DP-16-QAM. This will have a passband of about 75GHz. It is also possible to put each of the two channels in separate 50GHz-spaced channels and use existing networks The effective bandwidth will then be 100GHz for a 400GHz signal. However, the OSNR performance for this format is about 5-6 dB worse than the 100Gbps super-channels. That equates to about a quarter of the reach at 100Gbps.

As a result, 100Gbps super-channels are more suited to long distance systems while 200Gbps super-channels are applicable to metro/ regional systems.

Since 200Gbps super-channels can use standard 50GHz spacing, they can be used in existing metro networks carrying a mix of traffic including 10Gbps and 40Gbps light paths.

"Both 400 Gig alternatives mentioned have a baud rate of about 32 Gig and therefore do not require a 64 Gbaud photo detector," says Olson. "If you want to go to a single channel 400G with 16-QAM or 32-QAM modulation, you will get 64Gbaud or 51Gbaud rate and then you will need the 64 Gig detector."

The single channel formats, however, have worse OSNR performance than 200Gbps super-channels, about 10-12 dB worse than 100Gbps, says Transmode, and have a similar spectral efficiency as 200Gbps super-channels. "So it is not the most likely candidates for 400 Gig," says Olson. "It is therefore unclear for us if this detector will have a use in 400 Gigabit transmission in the near future."

Transmode points out that the state-of-the-art bit rate has traditionally been limited by the available optics. This has kept the baud rate low by using higher order modulation formats that support more bits per symbol to enable existing, affordable technology to be used.

"But the price you have to pay, as you can not fool physics, is shorter reach due to the OSNR penalty," says Persson.

Now the challenges associated with the DSP-ASIC development will be equally important as the optics to further boost capacity.

The bundling of optical carriers into super-channels is an approach that scales well beyond what can be accomplished with improved optics. "Again, we have to pay the price, in this case eating greater portions of the spectrum," says Persson.

Improving the bandwidth of the balanced detector to the extent done by u2t is a very impressive achievement. But it will not make it alone into new products, modulators and a faster DSP-ASIC will also be required.

"From an industry point of view, a metro-centric cost reduction of 100Gbps coherent is currently more important than increasing the bit rate to 400Gbps," says Olson. "When 100 Gig coherent costs less than 10x10 Gig, both in dollars and watts, the technology will have matured to again allow for scaling the bit rate, using technology that suits the application best."

Ciena:

How the optical performance changes going from 32Gbaud to 64Gbaud depends largely on how well the DSP-ASIC can mitigate the dispersion penalties that get worse with speed as the duration of a symbol narrows.

BPSK goes twice as far as QPSK which goes about 4.5 times as far as 16-QAM

"I would also expect a higher sensitivity would be needed also, so another fundamental impact," says Joe Berthold, vice president of network architecture at Ciena. "We have quite a bit or margin with the WaveLogic 3 [DSP-ASIC] for many popular network link distances, so it may not be a big deal."

With a good implementation of a coherent transmission system, the reach is primarily a function of the modulation format. BPSK goes twice as far as QPSK which goes about 4.5 times as far as 16-QAM, says Berthold.

"On fibres without enough dispersion, a higher baud rate will go 25 percent further than the same modulation format at half of that baud rate, due to the nonlinear propagation effects," says Berthold. This is the opposite of what occurred at 10 Gigabit incoherent. On fibres with plenty of local dispersion, the difference becomes marginal, approximately 0.05 dB, according to Ciena.

Regarding how spectral efficiency changes with symbol rate, doubling the baud rate doubles the spectral occupancy, says Berthold, so the benefit of upping the baud rate is that fewer components are needed for a super-channel.

"Of course if the cost of the higher speed components are higher this benefit could be eroded," he says. "So the 200 Gbps signal using DP-QPSK at 64 Gbaud would nominally require 75GHz of spectrum given spectral shaping that we have available in WaveLogic 3, but only require one laser."

Does Ciena have an view as to when 64Gbaud systems will be deployed in the network?

Berthold says this hard to answer. "It depends on expectations that all elements of the signal path, from modulators and detectors to A/D converters, to DSP circuitry, all work at twice the speed, and you get this speedup for free, or almost."

The question has two parts, he says: When could it be done? And when will it provide a significant cost advantage? "As CMOS geometries narrow, components get faster, but mask sets get much more expensive," says Berthold.

Software-defined networking: A network game-changer?

OFC/NFOEC reflections: Part 1

"We [operators] need to move faster"

Andrew Lord, BT

Q: What was your impression of the show?

A: Nothing out of the ordinary. I haven't come away clutching a whole bunch of results that I'm determined to go and check out, which I do sometimes.

I'm quite impressed by how the main equipment vendors have moved on to look seriously at post-100 Gigabit transmission. In fact we have some [equipment] in the labs [at BT]. That is moving on pretty quickly. I don't know if there is a need for it just yet but they are certainly getting out there, not with live chips but making serious noises on 400 Gig and beyond.

There was a talk on the CFP [module] and whether we are going to be moving to a coherent CFP at 100 Gig. So what is going to happen to those prices? Is there really going to be a role for non-coherent 100 Gig? That is still a question in my mind.

"Our dream future is that we would buy equipment from whomever we want and it works. Why can't we do that for the network?"

I was quite keen on that but I'm wondering if there is going to be a limited opportunity for the non-coherent 100 Gig variants. The coherent prices will drop and my feeling from this OFC is they are going to drop pretty quickly when people start putting these things [100 Gig coherent] in; we are putting them in. So I don't know quite what the scope is for people that are trying to push that [100 Gigabit direct detection].

What was noteworthy at the show?

There is much talk about software-defined networking (SDN), so much talk that a lot of people in my position have been describing it as hype. There is a robust debate internally [within BT] on the merits of SDN which is essentially a data centre activity. In a live network, can we make use of it? There is some skepticism.

I'm still fairly optimistic about SDN and the role it might have and the [OFC/NFOEC] conference helped that.

I'm expecting next year to be the SDN conference and I'd be surprised if SDN doesn't have a much greater impact then [OFC/NFOEC 2014] with more people demoing SDN use cases.

Why is there so much excitement about SDN?

Why now when it could have happened years ago? We could have all had GMPLS (Generalised Multi-Protocol Label Switching) control planes. We haven't got them. Control plane research has been around for a long time; we don't use it: we could but we don't. We are still sitting with heavy OpEx-centric networks, especially optical.

"The 'something different' this conference was spatial-division multiplexing"

So why are we getting excited? Getting the cost out of the operational side - the software-development side, and the ability to buy from whomever we want to.

For example, if we want to buy a new network, we put out a tender and have some 10 responses. It is hard to adjudicate them all equally when, with some of them, we'd have to start from scratch with software development, whereas with others we have a head start as our own management interface has already been developed. That shouldn't and doesn't need to be the case.

Opening the equipment's north-bound interface into our own OSS (operating systems support) in theory, and this is probably naive, any specific OSS we develop ought to work.

Our dream future is that we would buy equipment from whomever we want and it works. Why can't we do that for the network?

We want to as it means we can leverage competition but also we can get new network concepts and builds in quicker without having to suffer 18 months of writing new code to manage the thing. We used to do that but it is no longer acceptable. It is too expensive and time consuming; we need to move faster.

It [the interest in SDN] is just competition hotting up and costs getting harder to manage. This is an area that is now the focus and SDN possibly provides a way through that.

Another issue is the ability to put quickly new applications and services onto our networks. For example, a bank wants to do data backup but doesn't want to spend a year and resources developing something that it uses only occasionally. Is there a bandwidth-on-demand application we can put onto our basic network infrastructure? Why not?

SDN gives us a chance to do something like that, we could roll it out quickly for specific customers.

Anything else at OFC/NFOEC that struck you as noteworthy?

The core networks aspect of OFC is really my main interest.

You are taking the components, a big part of OFC, and then the transmission experiments and all the great results that they get - multiple Terabits and new modulation formats - and then in networks you are saying: What can I build?

The networks have always been the poor relation. It has not had the great exposure or the same excitement. Well, now, the network is becoming centre stage.

As you see components and transmission mature - and it is maturing as the capacity we are seeing on a fibre is almost hitting the natural limit - so the spectral efficiency, the amount of bits you can squeeze in a single Hertz, is hitting the limit of 3,4,5,6 [bit/s/Hz]. You can't get much more than that if you want to go a reasonable distance.

So the big buzz word - 70 to 80 percent of the OFC papers we reviewed - was flex-grid, turning the optical spectrum in fibre into a much more flexible commodity where you can have wherever spectrum you want between nodes dynamically. Very, very interesting; loads of papers on that. How do you manage that? What benefits does it give?

What did you learn from the show?

One area I don't get yet is spatial-division multiplexing. Fibre is filling up so where do we go? Well, we need to go somewhere because we are predicting our networks continuing to grow at 35 to 40 percent.

Now we are hitting a new era. Putting fibre in doesn't really solve the problem in terms of cost, energy and space. You are just layering solutions on top of each other and you don't get any more revenue from it. We are stuffed unless we do something different.

The 'something different' this conference was spatial-division multiplexing. You still have a single fibre but you put in multiple cores and that is the next way of increasing capacity. There is an awful lot of work being done in this area.

I gave a paper [pointing out the challenges]. I couldn't see how you would build the splicing equipment, how you would get this fibre qualified given the 30-40 years of expertise of companies like Corning making single mode fibre, are we really going to go through all that again for this new fibre? How long is that going to take? How do you align these things?

"SDN for many people is data centres and I think we [operators] mean something a bit different."

I just presented the basic pitfalls from an operator's perspective of using this stuff. That is my skeptic side. But I could be proved wrong, it has happened before!

Anything you learned that got you excited?

One thing I saw is optics pushing out.

In the past we saw 100 Megabit and one Gigabit Ethernet (GbE) being king of a certain part of the network. People were talking about that becoming optics.

We are starting to see optics entering a new phase. Ten Gigabit Ethernet is a wavelength, a colour on a fibre. If the cost of those very simple 10GbE transceivers continues to drop, we will start to see optics enter a new phase where we could be seeing it all over the place: you have a GigE port, well, have a wavelength.

[When that happens] optics comes centre stage and then you have to address optical questions. This is exciting and Ericsson was talking a bit about that.

What will you be monitoring between now and the next OFC?

We are accelerating our SDN work. We see that as being game-changing in terms of networks. I've seen enough open standards emerging, enough will around the industry with the people I've spoken to, some of the vendors that want to do some work with us, that it is exciting. Things like 4k and 8k (ultra high definition) TV, providing the bandwidth to make this thing sensible.

"I don't think BT needs to be delving into the insides of an IP router trying to improve how it moves packets. That is not our job."

Think of a health application where you have a 4 or 8k TV camera giving an ultra high-res picture of a scan, piping that around the network at many many Gigabits. These type of applications are exciting and that is where we are going to be putting a bit more effort. Rather than the traditional just thinking about transmission, we are moving on to some solid networking; that is how we are migrating it in the group.

When you say open standards [for SDN], OpenFlow comes to mind.

OpenFlow is a lovely academic thing. It allows you to open a box for a university to try their own algorithms. But it doesn't really help us because we don't want to get down to that level.

I don't think BT needs to be delving into the insides of an IP router trying to improve how it moves packets. That is not our job.

What we need is the next level up: taking entire network functions and having them presented in an open way.

For example, something like OpenStack [the open source cloud computing software] that allows you to start to bring networking, and compute and memory resources in data centres together.

You can start to say: I have a data centre here, another here and some networking in between, how can I orchestrate all of that? I need to provide some backup or some protection, what gets all those diverse elements, in very different parts of the industry, what is it that will orchestrate that automatically?

That is the kind of open theme that operators are interested in.

That sounds different to what is being developed for SDN in the data centre. Are there two areas here: one networking and one the data centre?

You are quite right. SDN for many people is data centres and I think we mean something a bit different. We are trying to have multi-vendor leverage and as I've said, look at the software issues.

We also need to be a bit clearer as to what we mean by it [SDN].

Andrew Lord has been appointed technical chair at OFC/NFOEC

Further reading

Part 2: OFC/NFOEC 2013 industry reflections, click here

Part 3: OFC/NFOEC 2013 industry reflections, click here

Part 4: OFC/NFOEC industry reflections, click here

Part 5: OFC/NFEC 2013 industry reflections, click here