Optical core switching tops 4 Terabit-per-second.

Event:

Alcatel-Lucent has launched its 1870 Transport Tera Switch (TTS) that has a switch capacity of 4 Terabits-per-second (Tbps). The platform switches and grooms traffic at 1Gbps granularity while supporting lightpaths up to 100Gbps.

“It is designed to address the explosion of traffic in core networks, driven by video and the move to cloud computing among others,” says Alberto Valsecchi, vice president of marketing, optics activities at Alcatel-Lucent.

The 1870 TTS supports next-generation Optical Transport Network (OTN), carrier Ethernet and SONET/SDH protocols, as well as generalized multiprotocol label switching/ automatically switched optical network(GMPLS/ ASON) control plane technology to enable network management and traffic off-load between the IP core and optical layers.

"

It [the 1870 TTS] is designed to address the explosion of traffic in core networks"

Alberto Valsecchi, Alcatel-Lucent

Central to the 1870 TTS is an in-house-designed 1Tbps switch integrated circuit (IC). The switch chip is non-blocking and by switching at the OTN level supports all traffic types. The device is designed to limit power consumption and is claimed to consume 0.04 Watts per Gbps. Four such ICs are required to achieve the 4Tbps switch capacity.

Each platform line card has a 120Gbps capacity and supports 1, 2.5, 10 and 40Gbps interfaces with a 100Gbps interface planned. The line card’s optical transceiver interfaces include 12 XFPs or two CFP modules. Three 40Gbps interfaces will be supported in future and a 240Gbps line card is already being mentioned (Alcatel-Lucent describes the platform as ‘8Tbps hardware ready’).

The cards also use tunable XFP modules. The 1870 TTS can thus be used alongside existing optical platforms for long-haul dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) transport or support its own links. “There is urgency for this [platform] to manage bandwidth in the central office,” says Michael Sedlick, head of cross-connect product line management at Alcatel-Lucent. “It can solve both requirements: working with installed based WDM platforms and enabling a more integrated implementation [using tunable XFPs].”

“It is already in trials and is selected by tier one service providers,” says Valsecchi.

Why is it important:

Gazettabyte asked three experts to give their views on the announcement. In particular, to position the 1870 TTS platform, discuss its significance, and the importance of GMPLS/ ASON support.

Ron Kline, principal analyst, network infrastructure at Ovum

The platform announcement is essentially about solving three key [service provider] dilemmas: scaling to meet the huge growth in traffic, working through the transition from SONET/SDH to Ethernet and driving efficiencies in the network through automation that helps reduce capital expenditure and operational expenditure.

The 1870 TTS is not a new class of platform but rather the next generation of bandwidth management systems that is using electrical OTN switching rather than STS-1 [SONET frame] switching.

Alcatel-Lucent’s existing 1850 packet optical transport system is really the next generation of aggregation (optical edge device/ multi-service provisioning platform) equipment. The difference is where the device goes in the network and the granularity of the switching.

For the 1870, you are switching bandwidth at wavelength rates (2.5G, 10G, 40G, etc.) There is also some sub-wavelength granularity as well. The device is protocol independent because client signals (SONET/SDH, Ethernet, video, etc) are all encapsulated in the OTN wrapper.

The most similar platforms are the Ciena 5400 introduced in September ’09 and Huawei’s OSN 8800. Tellabs also introduced a high-speed shelf for the 7100 that has a 1.2Tbps OTN matrix and ZTE has the ZXONE 8600 that it introduced in March ’09.

Momentum has been building for several years now. The current generation of optical core switches (Ciena's CoreDirector, Alcatel-Lucent's 1678 MCC, the Sycamore 16000) cannot scale large enough and are SONET/SDH based. The need is to be able to groom at the wavelength level. Current switch sizes (640Gbps, 1.2 Tbps for Sycamore) can’t scale so you have to place another switch and also use capacity to tie the switches together. The larger you grow the bigger the problem—you use 10% of capacity to tie two machines together, 20% to tie 3 together, etc.

In addition, older generation optical core switches are SONET/SDH-based and have trouble with Ethernet so they have to use the generic framing procedure/ virtual concatenation (GFP/VCAT) to manipulate the signal. When you move to OTN switching you don’t have to convert between protocols to switch through the matrix.

And yes, so far 4Tbps is the highest switch capacity per chassis.

As for the control plane, ASON automates configuration so it is more applicable for turning up and down bandwidth. In Alcatel-Lucent’s case, it is integrating the control planes across its product portfolio which gives visibility across the entire network. Although router offload is a key application for the device, you don’t necessarily need a control plane to do it.

IP routing is much more expensive (per bit) then wavelength switching. The idea is to switch at the lowest network layer possible. People have been using an inverted triangle with 4 layers to illustrate. IP routing is at the top followed by layer-2 switching, TDM/OTN switching and then wavelength switching.

Eve Griliches, managing partner, ACG Research

The 1870 TTS isn’t a new platform class but the platforms in general are new. Huawei, Fujitsu, Tellabs, Cisco and various others have platforms all geared towards this but most are missing some element today. In this case, Alacatel-Lucent is still missing the optical portion of the product [DWDM and ROADM].

The platform is starting out as a large OTN and packet switch which will eventually turn into a full packet optical transport product - that is my estimate. Each vendor is approaching this area differently, suffice to say, I think this is an OK and decent approach.

The GMPLS/ ASON control plane technology means the 1870 TTS can manage the optical and IP layers together. Some providers want that, some don't.

Andrew Schmitt, directing analyst, optical, Infonetics Research

The 1870 TTS is a lot like the 1850, just bigger. I suspect much of the new functionality in the 1870 will migrate down to the 1850.

The 1870 TTS is a lot like the 1850, just bigger. I suspect much of the new functionality in the 1870 will migrate down to the 1850.

It is significant as there are not that many boxes - none, really - that can do converged SDH/OTN/layer-2 switching all on one backplane. Several other vendors such as Ciena with its 5400, Cyan and Tellabs are going in this direction but Alcatel-Lucent has some legitimacy since it already was out with the 1850. Only the Fujitsu 9500 is in this class.

GMPLS/ ASON allow routers to communicate with the layer one infrastructure and set up and tear down paths as needed. It gives the router visibility into the lower layers of the OSI stack.

I think the key point is really the 1870 TTS’s 4Tbps switch capacity. This box represents the cutting edge of converged layer-1 plus layer-2 packet optical transport system technology.

Now we will see whether carriers adopt this architecture or whether they use IP over WDM or OTN switching only.

The Alcatel-Lucent 1870 TSS: the two central cards, larger than a shelf, each contain four 1Tbps universal switch ICs. There are two cards per platform as one is used for redundancy.

The Alcatel-Lucent 1870 TSS: the two central cards, larger than a shelf, each contain four 1Tbps universal switch ICs. There are two cards per platform as one is used for redundancy.

Optical transceivers: Pouring a quart into a pint pot

Optical equipment and transceiver makers have much in common. Both must contend with the challenge of yearly network traffic growth and both are addressing the issue similarly: using faster interfaces, reducing power consumption and making designs more compact and flexible.

Yet if equipment makers and transceiver vendors share common technical goals, the market challenges they face differ. For optical transceiver vendors, the challenges are particularly complex.

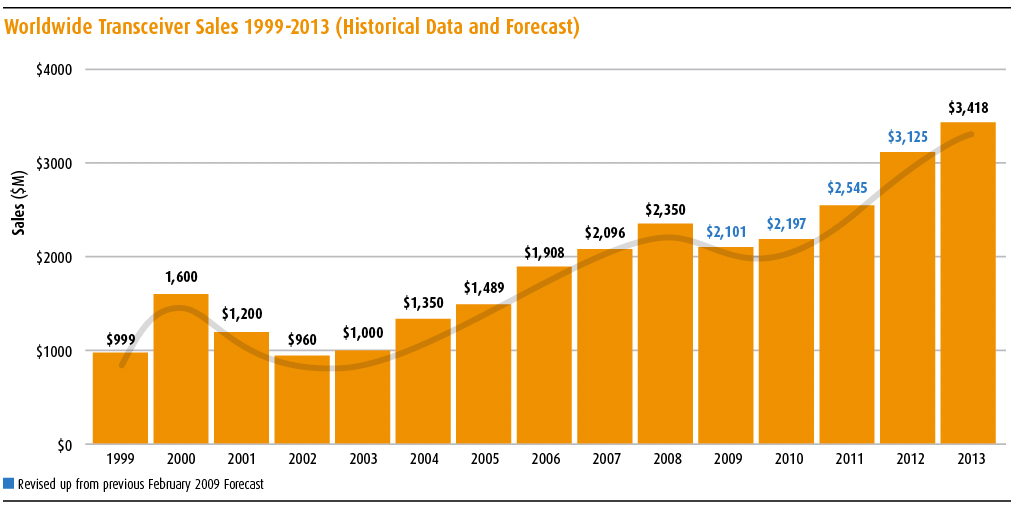

LightCounting's global optical transceiver sales forecast. In 2009 the market was $2.10bn and will rise to $3.42bn in 2013

LightCounting's global optical transceiver sales forecast. In 2009 the market was $2.10bn and will rise to $3.42bn in 2013

Transceiver vendors have little scope for product differentiation. That’s because the interfaces are based on standard form factors defined using multi-source agreements (MSAs).

System vendors may welcome MSAs since it increases their choice of suppliers but for transceiver vendors it means fierce competition, even for new opportunities such as 40 and 100 Gigabit Ethernet (GbE) and 40 and 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) long-haul transmission.

Transceiver vendors must also contend with 40Gbps overlapping with the emerging 100Gbps market. Vendors must choose which interface options to back with their hard-earned cash.

Some industry observers even question the 40 and 100Gbps market opportunities given the continual cost reduction and simplicity of 10Gbps transceivers. One is Vladimir Kozlov, CEO of optical transceiver market research firm, LightCounting.

“The argument heard is that 40Gbps will take over the world in two or three years’ time,” says Kozlov. Yet he has been hearing the same claim for over a decade: “Look at the relative prices of 40Gbps and 10Gbps a decade ago and look at it now – 10Gbps is miles ahead.”

In Kozlov’s view, while 40Gbps and 100Gbps are being adopted in the network, the vast majority of networks will not see such rates. Instead traffic growth will be met with additional 10Gbps wavelengths and where necessary more fibre.

“Look at the relative prices of 40Gbps and 10Gbps a decade ago and look at it now – 10Gbps is miles ahead.”

Vladimir Kozlov, LightCounting.

And despite the activity surrounding new pluggable transceivers such as the 40 and 100Gbps CFP MSA and long-haul modulation schemes, his view is that “99% of the market is about simplicity and low cost”.

Juniper Networks, in contrast, has no doubt 100Gbps interfaces will be needed.

First demand for 100Gbps will be to simplify data centre connections and link the network backbone. “Link aggregating 10Gbps channels involves multiple fibres and connections,” says Luc Ceuppens, senior director of marketing, high-end systems business unit at Juniper. “Having a single 100 Gigabit interface simplifies network topology and connections.”

Longer term, 100Gbps will be driven when the basic currency of streams exceeds 10Gbps. “You won’t have to parse a greater-than-10 Gig stream over two 10Gbps links,” says Ceuppens.

But faster line rates is only one way equipment vendors are tackling traffic growth and networking costs.

"Forty Gig and eventually 100 Gig are basic needs for data centre connections and backbone networks, but in the metro, higher line rate is not the only way to handle traffic growth cost effectively,” says Mohamad Ferej, vice president of R&D at Transmode. He points to lowering equipment’s cost, power consumption and size as well as enhancing its flexibility.

Compact designs equate to less floor space in the central office, while the energy consumption of platforms is a growing concern. Tackling both reduce operational expenses.

Greater platform flexibility using tunable components and pluggable transceivers also helps reduce costs. Tunable-laser-based transceivers slash the number of spare fixed-wavelength dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) transceivers operators and system vendors must store. Meanwhile, pluggables reduce costs by increasing competition and decoupling optics from the line card.

For higher speed interfaces, optical transmission cost – the cost-per-bit-per-kilometre - is reduced only if the new interface’s bandwidth grows faster than its cost relative to existing interfaces. The rule-of-thumb is that the transition to a new 4x line rate occurs once it matches 2.5x the existing interface’s cost. This is how 10Gbps superceded 2.5Gbps rates a decade ago.

The reason widespread adoption of 40Gbps has not happened is that 40Gbps has still to meet the crossover threshold. Indeed by 2012, 40Gbps will only be at 4x 10Gbps’ cost, according to market research firm, Ovum.

Thus it is the economics of 40 and 100Gbps as well as power and size that preoccupies module vendors.

Modulation war

“If the 40Gbps module market is at Step 1, 10Gbps is at Step 4,” says ECI Telecom’s Oren Marmur, vice president, optical networking line of business, network solutions division. Ten Gigabit has gone through several transitions; from 300-pin large form factor (LFF) to 300-pin small form factor (SFF) to the smaller fixed-wavelength pluggable XFP and now the tunable XFP. “Forty Gig is where 10 Gig modules were three years’ ago - each vendor has a different form factor and a different modulation scheme,” says Marmur.

DPSK dominates 40Gbps module shipments

DPSK dominates 40Gbps module shipments

Niall Robinson, Mintera

There are four modulation scheme choices for 40Gbps. First deployed has been optical duo-binary, followed by two phased-based modulation schemes: differential phase-shift keying (DPSK) and differential quadrature phase-shift keying (DQPSK). The phase modulation schemes offer superior reach and robustness to dispersion but are more complex and costly designs.

Added to the three is the emerging dual-polarisation, quadrature phase-shift keying (DP-QPSK), already deployed by operators using Nortel’s system and now being developed as a 300-pin LFF transponder by Mintera and JDS Uniphase. Indeed several such designs are expected in 2010.

Mintera has been shipping its 300-pin LFF adaptive DPSK transponder, and claims DPSK dominates 40Gbps module shipments. “DQPSK is being shipped in Japan and there is some interest in China but 90% is DPSK,” says Niall Robinson, vice president of product marketing at Mintera.

Opnext offers four 40Gbps transponder types: duo-binary, DPSK, a continuous mode DPSK variant that adapts to channel conditions based on the reconfigurable optical add/drop multiplexing (ROADM) stages a signal encounters, and a DQPSK design.

"40Gbps coherent channel position must be managed"

Daryl Inniss, Ovum

According to an Ovum study, duo-binary is cheapest followed by DPSK. The question facing transponder vendors is what next? Should they back DQPSK or a 40Gbps coherent DP-QPSK design?

“The problem with DQPSK is that it is more costly, though even coherent is somewhat expensive,” says Daryl Inniss, practice leader components at Ovum. The transponders’ bill of materials is only part of the story; optical performance being the other factor.

DQPSK has excellent performance when encountering dispersion while 40Gbps coherent channel position must be managed when used alongside 10Gbps wavelengths in the fibre. “It is not a big deal but it needs to be managed,” says Inniss. If price declines for the two remain equal, DQPSK will have the larger volumes, he says.

Another consideration is 100Gbps modules. DP-QPSK is the industry-backed modulation scheme for 100Gbps and given the commonality between 40 and 100Gbps coherent designs, the issue is their relative costs.

“The right question people are asking is what are the economics of 40 Gig versus 100 Gig coherent,” says Rafik Ward, Finisar's vice president of marketing. “If you buy 40 Gig and shortly after an economical 100 Gig coherent design appears, will 40 Gig coherent get the required market traction?”

Meanwhile, designers are shrinking existing 40Gbps modules, boosting significantly 40Gbps system capacity.

The 300-pin LFF transponder, at 7x5 inch, requires its own line card. As such, two system line cards are needed for a 40Gbps link: one for the short-reach, client-side interface and one for the line-side transponder.

A handful: a 300-pin large form factor transponder Source: Mintera

A handful: a 300-pin large form factor transponder Source: Mintera

Mintera is one vendor developing a smaller 300-pin MSA DPSK transponder that will enable the two 40Gbps interfaces on one card.

“At present there are 16 slots per shelf supporting eight 40Gbps links, and three shelves per bay,” says Robinson. Once vendors design a new line card, system capacity will double with 16, 40Gbps links (640Gbps) per shelf and 1,920Gbps capacity per system. Equipment vendors can also used the smaller pin-for-pin compatible 300-pin MSA on existing cards to reduce costs.

Matt Traverso, senior manager, technical marketing at Opnext also stresses the importance of more compact transponders: “Right now though it is a premature. The issue still is the modulation format war.”

Another factor driving transponder development is the electrical interface used. The 300-pin MSA uses the SFI 5.1 interface based on 16, 2.5Gbps channels. “Forty and 100GbE all use 10Gbps interfaces, as do a lot of framer and ASIC vendors,” says Traverso. Since the 300-pin MSA in not compatible, adopting 10Gbps-channel electrical interfaces will likely require a new pluggable MSA for long haul.

CFP MSA for 40 and 100 Gig

One significant MSA development in 2009 was the CFP pluggable transceiver MSA. At ECOC last September, several companies announced first CFP designs implementing 40 and 100GbE standards.

Opnext announced a 100GBASE-LR4 CFP, a 100GbE over 10 km interface made up of four wavelengths each at 25Gbps. Finisar and Sumitomo Electric each announced a 40GBASE-LR4 CFP, a 40GbE over 10km comprising four wavelengths at 10Gbps.

The CFP MSA is smaller than the 300-pin LFF, measuring some 3.4x4.8 inches (86x120mm). It has four power settings - up to 8W, up to 16W, below 24W and above 24W (to 32W). When a CFP is plugged in, it communicates to the host platform its power class.

The 100Gbps CFP is designed to link IP routers, or an IP router to a DWDM platform for longer distance transmission.

“There is customer-pull to get the 100 Gig [pluggable] out,” says Traverso, explaining why Opnext chose 100GbE for its first design.

Opnext’s 100GbE pluggable comprises four 25Gbps transmit optical sub-assemblies (TOSAs) and four receive optical sub-assemblies (ROSAs). Also included are an optical multiplexer and demultiplexer to transmit and recover the four narrowly (LAN-WDM) spaced wavelengths. Also included within the 100GbE CFP are two integrated circuits (ICs): a gearbox IC translating between the 10Gbps channels and the higher speed 25Gbps lanes, and the module’s electrical interface IC.

"The issue still is the modulation format war”

Matt Traverso, Opnext

The CFP transceiver, while relatively large, has space constraints that challenge the routeing of fibres linking the discrete optical components. “This is familiar territory,” says Traverso. “The 10GBASE-LX4 [a four-channel design] in an X2 [pluggable] was a much harder problem.”

“Right now our [100GbE] focus is the 10 km CFP,” says Juniper’s Ceuppens. “There is no interest in parallel multimode [100GBASE-SR10] - service providers will not deploy multi-mode fibre due to the bigger cable and greater weight.”

Finisar’s and Sumitomo Electric’s 40GBASE-LR4 CFP also uses four TOSAs and ROSAs, but since each is 10Gbps no gearbox IC is needed. Moreover, coarse WDM (CWDM)-based wavelength spacing is used avoidng the need for thermal cooling. The cooling is required for 100Gbps to restrict the lasers’ LAN-WDM wavelengths drifting. Finisar has since detailed a 100GBASE-LR4 CFP.

“For the 40GBASE-LR4 CFP, a discrete design is relatively straightforward,” says Feng Tian, senior manager marketing, device at Sumitomo Electric Device Innovations. Vendors favour discretes to accelerate time-to-market, he says. But with second generation designs, power and cost reduction will be achieved using photonic integration.

Reflex Photonics announced dual 40GBASE-SR4 transceivers within a CFP in October 2009. The SR4 specification uses a 4-channel multimode ribbon cable for short reach links up to 150 m. The short reach CFP designs will be used for connecting routers to DWDM platforms for telecom and to link core switch platforms within the largest data centres. “Where the number of [10Gbps] links becomes unwieldy,” says Robert Coenen, director of product management at Reflex Photonics.

Reflex’s 100GbE design uses a 12x photo-detector array and a 12x VCSEL array. For the 100GbE design, 10 of the 12 channels are used, while for the 2x40GbE, eight (2x4) channels of each array are used (see diagram). “We didn’t really have to redesign [the 100GbE]; just turn off two lanes and change the fibering,” says Coenen.

Meanwhile switch makers are already highlighting a need for more compact pluggables than the CFP.

“The CFP standard is OK for first generation 100Gbps line cards but denser line cards are going to require a smaller form factor,” says Pravin Mahajan, technology marketer at Cisco Systems.

This is what Cube Optics is addressing by integrating four photo-detectors and a demultiplexer in a sub-assembly using its injection molding technology. Its 4x25Gbps ROSA for 100GbE complements its existing 4x10 CWDM ROSA for 40GbE applications.

“The CFP is a nice starting point but there must be something smaller, such as a QSFP or SFP+,” says Sven Krüger, vice president product management at Cube Optics.

The company has also received funding for the development of complementary 4x25Gbps and 4x10Gbps TOSA functions. “The TOSA is more challenging from an optical alignment point of view; the lasers have a smaller coupling area,” says Francis Nedvidek, Cube Optic’s CEO.

Cube Optics forecasts second generation 40GbE and 100GbE transceiver designs using its integrated optics to ship in volume in 2011.

Could the CFP be used beyond 100GbE for 100Gbps line side and the most challenging coherent design?

“The CFP with its smaller size is a good candidate,” says Sumitomo’s Tian. “But power consumption will be a challenge.” It may require one and maybe two more CMOS process generations to be used beyond the current 65nm to reduce the power consumption sufficiently for the design to meet the CFP’s 32W power limit, he says.

XFP put to new uses

Established pluggables such as the 10Gbps XFP transceiver also continue to evolve.

Transmode is shipping XFP-based tunable lasers with its systems, claiming the tunable XFP brings significant advantages.

In turn, Menara Networks is incorporating system functionality within the XFP normally found only on the line card.

Until now deploying fixed-wavelength DWDM XFPs meant a system vendor had to keep a sizable inventory for when an operator needed to light new DWDM wavelengths. “With no inventory you have to wait for a firm purchase order from your customer before you know which wavelengths to order from your transceiver vendor, and that means a 12-18 weeks delivery time,” says Ferej. Now with a tunable XFP, one transceiver meets all the operator’s wavelength planning requirements.

Moreover, the optical performance of the XFP is only marginally less than a tunable 10Gbps 300-pin SFF MSA. “The only advantage of a 300-pin is a 2-3dB better optical signal-to-noise ratio, meaning the signal can pass more optical amplifiers, required for longer reach” says Ferej.

Using a 300-pin extends the overall reach without a repeater beyond 1,000 km. “But the majority of the metro network business is below 1000 km,” says Ferej.

Does the power and space specifications of an MSA such as the XFP matter for component vendors or do they just accept it?

“It doesn’t matter till it matters,” says Padraig OMathuna, product marketing director at optical device maker, GigOptix. The maximum power rating for an XFP is 3.5W. “If you look inside a tunable XFP, the thermo-electric cooler takes 1.5 to 2W, the laser 0.5W and then there is the TIA,” says OMathuna. “That doesn’t leave a lot of room for our modulator driver.”

Inside JDS Uniphase's tunable XFP

Inside JDS Uniphase's tunable XFP

Meanwhile, Menara Networks has implemented the ITU-T’s Optical Transport Network (OTN) in the form of an application specific IC (ASIC) within an XFP.

OTN is used to encapsulate signals for transport while adding optical performance monitoring functions and forward error correction. By including OTN within a pluggable, signal encapsulation, reach and optical signal management can be added to IP routers and carrier Ethernet switch routers.

The approach delivers several advantages, says Siraj ElAhmadi, CEO of Menara Networks.

First, it removes the need for additional 10Gbps transponders to ready the signals from the switch or router for DWDM transport. Second, system vendors can develop a universal linecard without supporting OTN functionality.

The biggest technical challenge for Menara was not developing the OTN ASIC but the accompanying software. “We had the chip one and a half years before we shipped the product because of the software,” says ElAhmadi. “There is no room [within the XFP] for extra memory.”

Menara is supplying its OTN pluggables to a North American cable operator.

ECI Telecom is one vendor using Menara’s pluggable for its carrier Ethernet switch router (CESR) platforms. “For certain applications it saves you having to develop OTN,” says Jimmy Mizrahi, next-generation networking product line manager, network solutions division at ECI Telecom.

Pluggables and optical engines

The CFP is one module that will be used in the data center but for high density applications - linking switches and high-performance computing - more compact designs are needed. These include the QSFP, the CXP and what are being called optical engines.

The CFP form factor for 40 and 100Gbps

The CFP form factor for 40 and 100Gbps

The QSFP is already the favoured interface for active optical cables that encapsulate the optics within the cable and which provide an attractive alternative to copper interconnect. QSFP transceivers support quad data rate (QDR) 4xInfiniband as well as extending the reach of 4x10Gbps Ethernet beyond copper’s 7m.

The QSFP is also an option for more compact 40GbE short-reach interfaces. “The [40GBASE-]SR4 is doable today as a QSFP,” says Christian Urricarriet, 40, 100GbE, and parallel product line manager at Finisar. The 40-GBASE-LR4 in a QSFP is also possible, as targeted by Cube Optics among others.

Achieving 100GbE within a QSFP is another matter. Adding a 25Gbps-per-channel electrical interface and higher-speed lasers while meeting the QSFP’s power constraints is a considerable challenge. “There may need to be an intermediate form factor that is better defined [for the task],” says Urricarriet.

Meanwhile, the CXP is a front panel interface that promises denser interfaces within the data centre. “CXP is useful for inter-chassis links as it stands today,” says Cisco’s Mahajan.

According to Avago Technologies, Infiniband is the CXP’s first target market while 100GbE using 10 of the 12 channels is clearly an option. But there are technical challenges to be overcome before the CXP connector can be used for 100GbE Ethernet. “You need to be much more stringent to meet the IEEE optical specification,” says Sami Nassar, director of marketing, fiber optic products division at Avago Technologies.

The CXP is also entering territory until recently the preserve of the SNAP12 parallel optics module. SNAP12 connects the platforms within large IP router configurations, and is used for high-end computing. However, it is not a pluggable and comprises separate 12-channel transmitter and receiver modules. SNAP12 has a 6.25Gbps per channel data rate although a 10Gbps per channel has been announced.

“Both [the CXP and SNAP12] have a role,” says Reflex’s Coenen. SNAP12 is on the mother board and because it has a small form factor it can sit close to the ASIC, he says.

Such an approach is now being targeted by firms using optical engines to reduce the cost of parallel interfaces and address emerging high-speed interface requirements on the mother-board, between racks and between systems.

Luxtera’s OptoPHY is one such optical engine. There are two versions: a single channel 10Gbps and a 4x10Gbps product, while a 12-channel version will sample later this year.

The OptoPHY uses the same optical technology as Luxtera’s AOC: a 1490nm distributed feedback (DFB) laser is used for both one and four-channel products, modulated using the company’s silicon photonics technology. The single channel consumes 450mW while the four-channel consumes 800mW, says Marek Tlalka, vice president of marketing at Luxtera, while reach is up to 4km.

Luxtera says the 12-channel version which will cost around $120, equating to $1 per 1Gbps. This, it claims, is several times cheaper than SNAP12.

“The next-generation product will achieve 25Gbps per channel, using the same form factor and the same chip,” says Tlalka. This will allow the optical engine to handle channel speeds used for 100GbE as well as the next Infiniband speed-hike known as Eight Data Rate (EDR).

Avago, a leading supplier of SNAP12, says that the robust interface with its integrated heat sink is still a preferred option for vendors. “For others, with even higher-density concentrations, a next generation packaging type is being used, which we’ve not announced yet,” says Dan Rausch, Avago’s senior technical marketing manager, fiber optic products division.

The advent of 100GbE and even higher rates, and 25Gbps electrical interfaces, will further promote optical engines. “It is hard enough to route 10Gbps around an FR4 printed circuit board,” says Coenen. Four inches are typically the limit, while longer links up to 10 inches requiring such techniques as pre-emphasis, electronic dispersion compensation and retiming.

At 25Gbps distances will become even shorter. “This makes the argument for optical engines even stronger, you will need them near the ASICs to feed data to the front panel,” says Coenen.

Optical transceivers may rightly be in the limelight handling network traffic growth but it is the activities linking platforms, boards and soon on-board devices where optical transceiver vendors, unencumbered by MSAs, have scope for product differentiation.

Differentiation in a market that demands sameness

At first sight, optical transceiver vendors have little scope for product differentiation. Modules are defined through a multi-source agreement (MSA) and used to transport specified protocols over predefined distances.

“Their attitude is let the big guys kill themselves at 40 and 100 Gig while they beat down costs"

Vladimir Kozlov, LightCounting

“I don’t think differentiation matters so much in this industry,” says Daryl Inniss, practice leader components at Ovum. “Over time eventually someone always comes in; end customers constantly demand multiple suppliers.”

It is a view confirmed by Luc Ceuppens, senior director of marketing, high-end systems business unit at Juniper Networks. “We do look at the different vendors’ products - which one gives the lowest power consumption,” he says. “But overall there is very little difference.”

For vendors, developing transceivers is time-consuming and costly yet with no guarantee of a return. The very nature of pluggables means one vendor’s product can easily be swapped with a cheaper transceiver from a competitor.

Being a vendor defining the MSA is one way to steal a march as it results in a time-to-market advantage. There have even been cases where non-founder companies have been denied sight of an MSA’s specification, ensuring they can never compete, says Inniss: “If you are part of an MSA, you are very definitely at an advantage.”

Rafik Ward, vice president of marketing at Finisar, cites other examples where companies have an advantage.

One is Fibre Channel where new data rates require high-speed vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers (VCSELs) which only a few companies have.

Another is 100 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) for long-haul transmission which requires companies with deep pockets to meet the steep development costs. “One hundred Gigabit is a very expensive proposition whereas with the 40 Gigabit Ethernet LR4 (10km) standard, existing off-the-shelf 10Gbps technology can be used,” says Ward.

"One hundred Gigabit is a very expensive proposition"

"One hundred Gigabit is a very expensive proposition"

Rafik Ward, Finisar

Ovum’s Inniss highlights how optical access is set to impact wide area networking (WAN). The optical transceivers for passive optical networking (PON) are using such high-end components as distributed feedback (DFB) lasers and avalanche photo-detectors (APDs), traditionally components for the WAN. Yet with the higher volumes of PON, the cost of WAN optics will come down.

“With Gigabit Ethernet the price declines by 20% each time volumes double,” says Inniss. “For PON transceivers the decline is 40%.” As 10Gbps PON optics start to be deployed, the price benefit will migrate up to the SONET/ Ethernet/ WAN world, he says. Accordingly, those transceiver players that make and use their own components, and are active in PON and WAN, will most benefit.

“Differentiation is hard but possible,” says Vladimir Kozlov, CEO of optical transceiver market research firm, LightCounting. Active optical cables (AOCs) have been an area of innovation partly because vendors have freedom to design the optics that are enclosed within the cabling, he says.

AOCs, Fibre Channel and 100Gbps are all examples where technology is a differentiator, says Kozlov, but business strategy is another lever to be exploited.

On a recent visit to China, Kozlov spoke to ten local vendors. “They have jumped into the transceiver market and think a 20% margin is huge whereas in the US it is seen as nothing.”

The vendors differentiate themselves by supplying transceivers directly to the equipment vendors’ end customers. “They [the Chinese vendors] are finding ways in a business environment; nothing new here in technology, nothing new in manufacturing,” says Kozlov.

He cites one firm that fully populated with transceivers a US telecom system vendor’s installation in Malaysia. “Doing this in the US is harder but then the US is one market in a big world,” says Kozlov.

Offshore manufacturing is no longer a differentiator. One large Chinese transceiver maker bemoaned that everyone now has manufacturing in China. As a result its focus has turned to tackling overheads: trimming costs and reducing R&D.

“Their attitude is let the big guys kill themselves at 40 and 100 Gig while they beat down costs by slashing Ph.Ds, optimising equipment and improving yields,” says Kozlov. “Is it a winning approach long term? No, but short-term quite possibly.”

Do multi-source agreements benefit the optical industry?

System vendors may adore optical transceivers but there is a concern about how multi-source agreements originate.

Optical transceiver form factors, defined through multi-source agreements (MSAs), benefit equipment vendors by ensuring there are several suppliers to choose from. No longer must a system vendor develop its own or be locked in with a supplier.

“Personally, the MSA is the worst thing that has happened to the optical industry”

“Personally, the MSA is the worst thing that has happened to the optical industry”

Marek Tlaka, Luxtera

Pluggables also decouple optics from the line card. A line card can address several applications simply by replacing the module. In contrast, with fixed optics the investment is tied to the line card. A system can also be upgraded by swapping the module with an enhanced specification version once it is available.

But given the variety of modules that datacom and telecom system vendors must support, there are those that argue the MSA process should be streamlined to benefit the industry.

Traditionally, several transceiver vendors collaborate before announcing an MSA. The CFP MSA announced in March 2009, for example, was defined by Finisar, Opnext and Sumitomo Electric Device Innovations. Since then Avago Technologies has become a member.

“The industry has an interesting model,” says Niall Robinson, vice president of product marketing at Mintera. “A couple of companies can get together, work behind closed doors and announce suddenly an MSA and try to make it defacto in the market.”

Robinson contrasts the MSA process with the Optical Interconnecting Forum’s (OIF) 100Gbps line side work that defined guidelines for integrated transmitter and receiver modules. Here service providers and system vendors also contributed. “It was a much more effective and fair process, allowing for industry collaboration,” says Robinson

Matt Traverso, senior manager, technical marketing at Opnext, and involved in the CFP MSA, also favours an open process. “But the view that the way MSAs are run is not open is a bit of a fallacy,” he says.

“Any MSA that is well run requires iteration with suppliers,” says Traverso. The opposite is also true: poorly run MSAs have short lives, he says. Having too open a forum also runs the risk of creating a one-size-fits-all: “One vendor may want to use the MSA as a copper interface while a carrier will want it for long-haul dense WDM.”

Optical transceiver vendors benefit in another way if they are the ones developing MSAs. “Transceiver vendors will not make life tough for themselves,” says Padraig OMathuna, product marketing director at optical device maker, GigOptix. “If MSAs are defined by system vendors, [transceiver] designs would be a lot more challenging.”

Avago Technologies argues for standards bodies to play a role especially as industry resources become more thinly spread.

“MSAs are not standards; there are items left unwritten and not enough double checking is done,” says Sami Nassar, director of marketing, fiber optic products division at Avago Technologies. There are always holes in the specifications, requiring patches and fixes. “If they [transceivers] were driven by standards bodies that would be better,” says Nassar.

Organisations such as the IEEE don’t address packaging and connectors as part of their standards work. But this may have to change. “The real challenge, as the industry thins out, is ensuring the [MSA] work is thorough,” says Dan Rausch, Avago’s senior technical marketing manager, fiber optic products division. “The challenge for the industry going forward is ensuring good engineering and more robust solutions.”

Marek Tlalka, vice president of marketing at Luxtera, goes further, questioning the very merits of the MSA: “Personally, the MSA is the worst thing that has happened to the optical industry.”

Unlike the semiconductor industry where a framer chip once on a line card delivers revenue for years, a transceiver company may design the best product yet six months later be replaced by a cheaper competitor. “The return on investment is lost; all that work for nothing,” says Tlalka.

“Is it a good development or not? MSAs are out there,” says Vladimir Kozlov, CEO of optical transceiver market research firm, LightCounting. “It helps system vendors, giving them a freedom to buy.”

But MSAs have squeezed transceiver makers, says Kozlov, and he worries that it is hindering innovation as companies cut costs to maximize their return on investment.

“There is continual pressure to reduce the price of optics,” adds Daryl Inniss, Ovum’s practice leader components. If operators are to provide video and high definition TV services and grow revenues then bandwidth needs to become dirt cheap. “Even today optics is not cheap,” says Inniss. Certainly MSAs play an important role in reducing costs.

“The transceiver vendors’ challenge is our benefit,” admits Oren Marmur, vice president, optical networking line of business, network solutions division at system vendor, ECI Telecom. “But we have our own challenges at the system level.”

Jagdeep Singh's Infinera effect

Talking to gazettabyte, he reflects on the ups and downs of being a CEO, his love of running, 40 Gigabit transmission and why he is looking forward to his next role at Infinera.

"We are looking to lead the 40 Gig market, not be first to market.”

Jagdeep Singh, Infinera CEO

Ask Jagdeep Singh about how Infinera came about and there is no mistaking the enthusiasm and excitement in his voice.

During the bubble era of 2000 he started to question whether the push to all-optical networking pursued by numerous start-ups made sense. “The reason for these all-optical device companies was that they were developing the analogue functions needed,” says Singh. “Yet what operators really wanted was access to the [digital] bits.”

This led him to think about optical-to-electrical (O-E) conversion and the digital processing of signals to correct for transmission impairments. “The question then was: could this be done in a low-cost way?” says Singh. Achieving O-E conversion would also allow access to the bits for add/ drop, switching and grooming functions at the sub-wavelength level before using inverse electrical-to-optical (E-O) conversion to continue the optical transmission.

“We came at this from an orthogonal direction: building lower-cost O-E-O. Was it possible?” says Singh. “The answer was that most of the cost was in the packaging and that led us to think about photonic integration.”

Singh started out with his colleague Drew Perkins (now Infinera’s CTO) with whom he co-founded Lightera, a company acquired by Ciena in 1999. Then the two met with Dave Welch at a Christmas party in 2000. Welch had been CTO of SDL, a company just acquired by JDS Uniphase. “It was clear that he was not that happy and there were a lot of VCs (venture capitalists) chasing him,” says Singh. “He (Welch) recognised the power of what we were planning.” In January 2001 the three founded Infinera.

So why is he stepping down as CEO? The answer is to focus on long-term strategy. And perhaps to reclaim time outside work, given he has a young family.

He may even have more time for running.

Singh typically runs at least two marathons a year. “As a CEO your schedule is fully booked. There is so much stuff there is no time to think.” Running for him is quiet time. “I can get out and recharge the batteries. I find it invaluable. I can process things and it keeps the stress levels down.”

Being CEO

“There are two roles to being a CEO: running the business – the P&Ls (profit and loss statements), financials, sales – all real-time and urgent; and then there is the second part – setting the product vision: what products will be needed in two, three, four years’ time?” he says.

This second part is particularly important for Infinera given it develops products around its photonic integrated circuit (PIC) designs, requiring a longer development cycle than other optical equipment makers. “We have to get the requirements right up front,” says Singh.

And it is this part of the CEO’s role, he says, that gets trumped due to real-time tasks that must be addressed. Thus, from January, Singh will become Infinera’s executive chairman focussing exclusively on product planning. “If I had to choose [between the two roles], the longer term stuff is more appealing,” he says.

Looking back over his period as CEO, he believes his biggest achievement has been the team assembled at Infinera. “What I’ve learnt over the years is that the quality of success depends on the quality of the team.

“We started after the telecom bust,” says Singh. “There were world-class people that were never that locked in and [once on board] they knew people that they respected.” Now Infinera has a staff of 1,000, and had gone from a start-up to a publicly-listed company.

One downside of becoming a large company is that Singh regrets no longer personally knowing all his staff. “What I miss is that I knew everyone, I was part of a small team with a lot of energy,” he says. Another change is all the regulatory, legal and accounting that a public company must do. “I was also free to do and say what I wanted. Now I have to be a lot more careful.”

The Infinera effect

Asked about why Infinera is still not shipping a PIC with 40Gbps line rate channels, it is Singh-as-scrutinised-CEO that kicks in. “If we built 40 Gig purely using off-the-shelf components we’d have a product.” But he argues that the economics of 40 Gigabit-per-second (Gbps) are still not compelling. According to market research firm Ovum, he says, it will only be 2012 when 40Gbps dips below four times the cost of 10Gbps.

Indeed in Q3 2009 shipments of 40Gbps slipped. According to Ovum, this was in part due to what it calls the “Infinera effect” that is lowering the cost of existing 10Gbps technology. Only when 40Gbps is around 2.5x the cost of 10Gbps that it is likely to take off; the economic rule-of-thumb with all previous optical speed hikes.

“Our goal is to come in with a 40 Gig solution that is economically viable,” says Singh. This is what Infinera is working on with its 10x40Gbps PIC pair of chips that integrate hundreds of optical functions. “With the PIC we are looking to lead the 40 Gig market, not be first to market.”

This year also saw Infinera introduce its second class of platform, the ATN, aimed at metro networks. The platform was developed across three Infinera sites: in Silicon Valley, India and China.

Coupled with Infinera’s DTN, the ATN allows end-to-end bandwidth management of its systems. “Until now we have only played in long-haul; this now doubles the market we play in,” says Infinera's CEO. Italian operator Tiscali announced in December 2009 its plan to deploy Infinera’s systems with the ATN being deployed in 80 metro locations.

How are cheap wavelength-selective switches and tunability impacting Infinera’s business? Singh bats away the question: “We just don’t see it in our space.”

Singh agrees with Infinera’s Dave Welch’s thesis that PICs are optics’ current disruption. What developments can he cite that will indicate this is indeed happening?

There are several examples that would confirm this, he says: “PICs in adjacent devices such as routers or switches; you would need something like a PIC to reduce the power and space of such platforms.” Other areas of adoption include connecting multiple bays such as required for the largest IP core routers, and even chip-to-chip interconnect.

Surely chip-to-chip is silicon photonics not Infinera’s PICs’ based on indium phosphide technology? Is silicon photonics of interest to Infinera?

"We are an optical transport company. To generate light over vast distances requires indium phosphide,” says Singh. “But if and when there is a breakthrough in silicon to generate light efficiently, we’d want to take advantage of that.”

One wonders what ideas Singh will come up with on his two-hour runs once he can think beyond the next financial quarter.

Best books of 2009?

Books I'd highlight this year are:

- The Nature of Technology by W Brian Arthur. A look at what technology is and how it advances. This is full of original thinking.

If you want to understand the latest cellular standards - the air interfaces and networking technologies - here are two recommended titles:

- 3G Evolution: HSPA and LTE for Mobile Broadband by Erik Dahlman, Stefan Parkvall, Johan Skold and Per Beming.

- LTE for UMTS: OFDMA and SC-FDMA based radio access by Harri Holma and Antti Toskala

The first title goes into more detail while the second is broader. As such the two are complementary. However, if only one title is to be chosen, it is 3G Evolution.

Click here for more information.

EPON becomes long reach

“Rural [PON deployment] is a tough proposition”

Barry Gray

Moreover, the TK3401 supports up to four such EPONs. The chip does not require changes to EPON’s optical transceivers although wavelength division multiplexing (WDM) transceivers are needed for the greater reach.

The TK3401 sits within what Barry Gray, director of marketing for Teknovus, calls the Intelligent PON Node (IPN). The IPN resides 20km from the subscriber’s optical network unit (ONU), where the PON’s optical line terminal (OLT) normally resides.

On one side of the IPN platform are sockets for up to four EPON OLT transceivers that support the PONs. On the other side are four SFP WDM transceivers that communicate with the central office up to 80km away and where the OLT platform is located. The OLT line card instead of using OLT optics uses WDM transceivers also in the SFP form factor. As such the line card does not require any redesign (see diagram).

Up to four point-to-point fibres can be used to connect the PONs’ traffic to the OLT, or a single fibre and up to 8 lambdas with coarse WDM (CWDM) technology to multiplex four PONs onto a single trunk fibre.

The 256 subscribers are achieved using a PX20+ specified optical transceiver. “It has a 28dB link budget such that going through 8 splitter stages is still sufficient for 2km distances [from the ONUs],” says Gray. “This is ideal for multi-dwelling unit deployments.”

Besides the pluggable optics, the IPN design includes the TK3401, a field programmable gate array (FPGA), and a flash memory.

The TK3401 comprises an EPON ONU media access controller (MAC), microprocessor and on-chip memory. The MAC registers the IPN with the central office OLT to set up remote IPN management and configuration communication links. The on-chip memory holds the firmware that configures the FPGA on start-up. The FPGA implements a crossbar switch to connect traffic from any of the EPONs to any of the WDM ports.

The IPN approach offers other advantages besides the 100km reach and increased subscriber count. It has a power consumption of 20W which means it can be powered from such locations as a telegraph pole. As the PONs are first populated, all four PONs’ traffic can also be aggregated into a single WDM link OLT port, with OLT ports added only when needed. In turn a fibre link can be used for protection with a sub-100ms restoration time.

However, unlike long reach PON or WDM-PON which also offer a 100km reach, the Teknovus scheme still requires the intermediate network node. The node is also active as it must be powered.

Teknovus claims it has strong interest from its IPN-based EPON architecture from operators in Japan and South Korea, while interest in China is for rural PON deployments. “Rural [PON deployment] is a tough proposition for service providers,” says Gray. “There is not the subscriber density and it is more expensive; the same is also true for mobile backhaul.”

The company is demonstrating the IPN to customers.

Click here for Teknovus' IPN presentation and White Paper

ROADMs: Set for double-digit growth

Summary

The wavelength-division multiplexing (WDM) reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexer (ROADM) equipment market will be the fastest growing optical segment over the next few years, according to Infonetics Research. The market research firm in its ROADM Components Market Outlook report predicts that the segment will grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13% from 2008 to 2013.

Q&A

Q. Can you please help by defining some terms? What is the difference between a wavelength-selective switch (WSS) and a ROADM?

AS: A WSS is a component that can direct individual wavelengths among multiple fibers. They are typically built in asymmetrical configurations, such as a 1x9 or a 9x1 and are used in quantity to build logical larger switches, effectively allowing multiple wavelengths to be switched among several incoming and outgoing fibers.

ROADMs are subsystems composed of these WSS modules but also include EDFA amplifiers, splitters, sometimes arrayed waveguide gratings (AWGs), and control electronics that include power balancing.

Q. A ROADM can also be colourless and directionless. What do these terms mean?

AS: For a ROADM to be colourless, it must be capable of dropping wavelengths of the same colour entering the node from both the West and East directions on individual drop ports. Directionless requires that wavelengths added at that node have non-blocking behavior and be capable of being routed either in the West or East direction. Removing these restrictions typically requires more WSSs to be used in the ROADM in place of AWGs, representing a classic flexibility/ cost tradeoff.

Q. In the report you split the WSS into two categories: those with up to four ports and those greater than four ports. Why?

AS: That’s really the breaking point of the market according to carriers I spoke with. Originally, four ports was a high end number but since then larger WSS modules have become available. The market has divided into small, which is 1x2 to 1x4 ports, and large, which at this point are 1x9’s.

"It is probably the only thing the circuit-loving Bell-heads and the counter-culture IP-bigots can agree on – everybody loves ROADMs."

"It is probably the only thing the circuit-loving Bell-heads and the counter-culture IP-bigots can agree on – everybody loves ROADMs."

Andrew Schmitt

Q. You say that ROADMs will be the faster growing optical equipment segment. What is motivating operators to deploy?

AS: ROADMs save money, plain and simple. When you use a ROADM, you eliminate the need to do an electrical-optical conversion and the electronics required to support it. It is particularly attractive for IP over WDM configurations, where expensive layer three router ports can be bypassed. Electrical-optical conversion is where the cost is in networks and ROADMs allow any given node to only touch the traffic required at that node. It’s probably the only thing the circuit-loving bell-heads and the counter-culture IP-bigots can agree on – everybody loves ROADMs.

Q. Are there regional differences in how ROADMs are being embraced? If so, why?

AS: North America, Japan and Europe have seen the bulk of deployments. But that has started to change with smaller carriers in developing countries adopting ROADM, particularly in Asia Pacific.

Q. Did you learn anything that surprised you as part of this research?

I assembled historical estimates of the WSS market back to 2005 through conversations with WSS vendors and equipment makers. Most people were very co-operative. When I was writing the final report, I overlayed historical WSS component revenue with the Infonetics’ ROADM optical equipment revenue we have tracked over the past years, and there was an extremely tight correlation. Where there wasn’t a correlation there was a logical reason behind it – adding more ROADM degrees to existing nodes.

Covering the component market and the equipment market makes the research much better than if I did each market individually. I’ve done a lot of research in the past few years in both technical and financial domains but this was the second most interesting – it was really refreshing to find a big double-digit growth market in optical.

Cisco System’s CEO, John Chambers, has been very public in his goal to grow the company at 15% annually, and I don’t think it is an accident that the Cisco optical group makes ROADM solutions a number one priority. They’ve silently moved up to second in market share for North American WDM, and their ROADM expertise played a big role in this.

The wavelength-division multiplexing (WDM) reconfigurable optical add-drop multiplexer (ROADM) equipment market will be the fastest growing optical segment over the next few years, according to Infonetics Research.

The market research firm in its ROADM Components Market Outlook report predicts that the segment will grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13% from 2008 to 2013.

Andrew Schmitt, directing analyst, optical at Infonetics discusses some of the issues regarding ROADMs and his report findings.

Retweet

"It's a bit like working with your wife; it has its ups and downs."

Siraj ElAhmadi, CEO of Menara Networks, on what it is like working with his brother, Salam, who is the company's CTO.

Titbits and tweets you may have missed

- ENISA has published a comprehensive report entitled Cloud Computing: Benefits, risks and recommendations for information security. The 125-page report can be downloaded from the ENISA site, click here.

- There is also a SecureCloud 2010 conference coming up in March involving ENISA and the Cloud Security Alliance, click here for details.

- A European court overruled German regulators that had allowed Deutsche Telekom to ban competitors from having access to its high-speed broadband network.

- Teknovus announced availability of the TK3401 EPON node controller that supports central office (OLT) to subscriber (ONU) distances of up to 100 km and up to 1,000 subscriber ONUs. And if you ever wondered what is the difference between the optical network unit (ONU) and optical network terminal (ONT), here is the answer.

- Broadcom announced its plan to acquire Dune Networks for $178m. Meanwhile, the 10GBASE-T copper interface got a shot in the arm with start-up Aquantia raising $44m in financing.

Retweet

Tidbits and tweets you may have missed

1. ENISA has published a comprehensive report entitled Cloud Computing: Benefits, risks and recommendations for information security. The 125 page report can be downloaded from the ENISA site, click here. http://tr.im/GC8x

2. A European court overruled German regulators that had allowed Duetche Telekom to ban competitors from having access to its high-speed broadband network. http://tr.im/GC7O

3. Teknovus announced availability of the TK3401 EPON node controller that supports central office (OLT) to subscriber (ONU) distances up to 100 km and connections to over 1,000 subscriber ONUs http://tr.im/GCe2 And if you evered wondered if there is a difference between the ONU and ONT here is the answer http://tr.im/GCgu

4. Broadcom announced its plan to acquire Dune Networks for $178m http://tr.im/GCf3

5. Meanwhile 10GBASE-T copper standard got a shot in the arm with start-up Aquantia gets $44m in financing http://bit.ly/6MCwdk

Quotes

"It's a bit like working with your wife; it has its ups and downs."

Siraj ElAhmadi, CEO of Menara Networks on what it is like working with his brother, Salam, who is the company's CTO.

The art of market analysis

Bob Larribeau, a telecom industry analyst and technology consultant since 1992 has just retired. gazettabyte asked him to reflect on what it takes to be a good market research analyst.

"Most companies provide good numbers but some, quite frankly, are hard to believe."

"Most companies provide good numbers but some, quite frankly, are hard to believe."

Bob Larribeau

There are several skills a good industry analyst must develop. The ability to communicate well - in writing, in presentations and in informal exchanges - is critical, as is a broad knowledge of the telecom industry and its technologies. These days the ability to have a global view - an understand of developed, developing, and emerging markets - is also important.

In addition, there are two more skills an analyst must possess.

The first is the ability to develop a detailed knowledge of the industries covered. For telecom this includes knowledge of the service providers and vendors and the products and services they offer. Regularly publishing reports that compare results and market positions of the service providers and vendors is an important part of this process.

This skill includes evaluating data provided by service providers and vendors. It is important that definitions are aligned to be able to compare results from companies. It also requires detecting when data is misleading or false. Most companies provide good numbers but some, quite frankly, are hard to believe.

An analyst may also have to develop their own market metrics since the statistics provided by the vendors are inadequate.

When I started following the IPTV market I found it necessary to develop ways to use service provider subscriber counts as a metric. This worked well for most segments, but I had to work with video encoder vendors to use the number of encoders sold. The video encoder firms were willing to provide such information to have an independent view of market position. Such metrics developed by the analyst can provide a good assessment of the market and are likely to be the only choice.

Reporting market positions is the most sensitive part of an analyst’s job. No company is happy when an analyst’s assessment of market position does not match the company's own. A few companies believe that they can improve their market position by being aggressive with an analyst. The analyst must be able to listen to the company but cannot be browbeaten into changing his or her assessment. The challenge is doing this without disrupting an important relationship.

The second analyst skill is the ability to provide a short and long term view based on the data an analyst develops. This includes identifying key trends and understanding how these trends will affect the markets they study as well as how they will affect the participants. Providing a strong strategic perspective is what characterises the best analysts.

I developed business models for several markets I studied. I found that a simple business model can provide a good perspective on the problems that service providers face. Ten years ago one of my models showed that the financial structure of unbundled access in the U.S. market would make it difficult for the competitive broadband providers to be profitable, which was indeed true.

Business case analysis also showed that WiMAX could be a strong competitor to wireline broadband and that it will be difficult for mobile TV operators to make a profit on the service.

I also developed ways of assessing future market opportunity. I showed that there were few opportunities left for vendors in the IPTV market even though there was major growth in subscribers ahead. This conclusion was based on the assumption that it will be difficult to disrupt existing service provider/ vendor relationships in most market segments. This has proved to be the case even though many aspiring vendors felt that the market would be more open.

I found being an analyst a good job. It provided plenty of opportunity for creativity and allowed me to work with a lot of great people.

Bob Larribeau has worked on his own and for RHK (now part of Ovum) where he was responsible for its access and switching and routing services. He was also affiliated with MRG where he made contributions in broadband and developed its IPTV service. In 2004 he co-founded TelecomView with Ian Cox, another RHK alumnus. TelecomView analysed the market for WiMAX as well as broadband and IPTV.

Bob’s first project was a private analysis of the commercial Internet in 1992. In that year, commercial Internet revenues were $15M. In 1999 he wrote an analysis for RHK that forecast that IP traffic was about to eclipse both ATM and circuit-switched voice traffic and predicted the coming importance of MPLS in IP networks. In 2001 he began covering the IPTV market. Bob can be contacted at bob@larribeau.com